We’ve discussed the early 1920s, so let’s address what came next.

We tend to think of Prohibition as the heyday of bootlegging and speakeasies…a vague, lawless period of time where old-timey whiskey traditions were thankfully superseded by the modern whiskey industry. We don’t tend to focus on the complete overhaul of the liquor industry that took place during the late 1920s…mostly because we exist in a new normal where we’re not asked to question the massive changes that took place during the 1920s and early 30s. The three-tier system seems normal to the modern consumer. The present focus of American whiskey production on bourbon manufacturers seems normal, but our understanding of American history is skewed. We don’t realize that the early years of Prohibition were plagued by bad actors diluting medicinal whiskey with neutral spirits or that many doctors were selling prescriptions. We tend to miss that the brick and mortar distilleries listed on all those old bottle labels no longer existed when those bottles were filled in 1927 or that only a handful of warehouse owners were selling the country’s medicinal whiskey stocks for a handsome profit. While it may seem that Prohibition was an age of gangsters and illegal activity, there was a great deal of legal and legitimate trade going on that was just as shady. It all shaped the future of American whiskey into something that the hundreds of-distillery owners thriving in the years before Prohibition would not have recognized.

1925 marked the return of whiskey to The Pharmacopeia of the United States of America– a reference book of standards, identities, and formulas for drugs/medicines. Whiskey and brandy had been removed in 1916 from the list of scientifically approved medicines. (The American Medical Association also voted to advocate for prohibition in 1917.) In 1920, Dr. Harvey Wiley (former chief chemist of the Dept of Agriculture and sponsor of the Food and Drug Act) and Wayne Wheeler (Anti-Saloon League) forced the issue again with a referendum at the American Medical Association’s yearly convention. The vote to approve whiskey and brandy as medicinal spirits was reintroduced, and with Wiley and Wheeler’s influence, the referendum passed with 55% of the vote. The United States Pharmacopeia did not include medicinal spirits for the first half of the decade, but was returned to the authoritative volume with new language revising its description. The new description read:

Medicinal whiskey or “spirits frumenti” is “an alcoholic liquor obtained by distillation of the fermented mash of wholly or partly malted cereal grains, and containing not less than 47 per cent and not more than 53 per cent by volume of C2H5OH (ethyl alcohol) at 55.56 degrees centigrade.” And as if Dr. Wiley had written this bit himself, it added, “must have been stored in charred wood containers for a period of not less than four years.”

Physicians varied on their opinions on whether or not whiskey had medicinal value, but most agreed that standards should at least be set. The assistant federal district attorney, John B. Osmun, explained away any connection of revisions to the US Pharmacopeia may have had with the Prohibition Bureau. “Whiskey’s entrance into the pharmacopeia is purely an act of the Department of Agriculture and was in no way inspired by prohibition enforcers.” (The Dayton Herald, Oct.25, 1925)

During Congressional discussions/debates in 1925 over the Treasury Department Appropriations Bill for 1927, Charles R. Nash, Assistant to the Commissioner of Internal Revenue shared a memorandum he received from his boss, Roy Haynes. The concentration of America’s liquor was proving difficult but efforts were still underway.

Memorandum for Mr. C. R. Nash, Assistant to the Commissioner (Attention Mr. Evans) .

Responsive to your memorandum of September 22 , 1925, the following information is submitted showing the status of work incident to concentration of spirits, to be used in support of estimate in the amount of $481,600 to cover the salaries of 280 storekeeper -gaugers and gaugers for the fiscal year 1927:

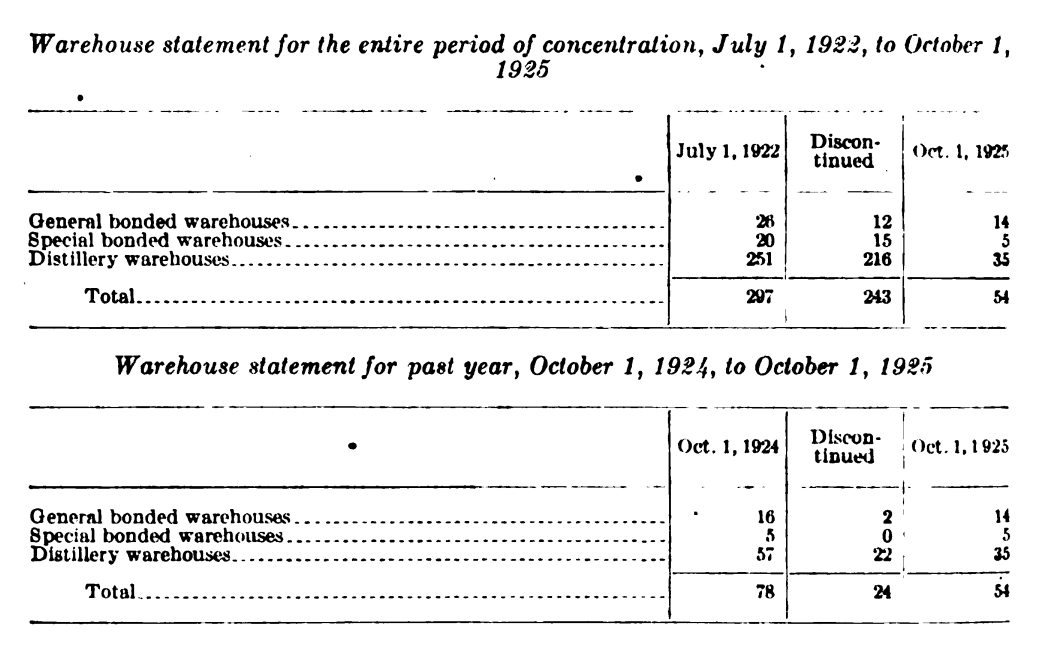

On July 1, 1922, when concentration operations first began, there were 26 general bonded warehouses, 20 special bonded warehouses , and 251 distillery warehouses, or a total of 297 internal- revenue bonded warehouses containing distilled spirits.

Since that time , 12 general bonded warehouses, 15 special bonded warehouses, and 216 distillery warehouses, or a total of 243 internal-revenue bonded ware houses, have been discontinued .

On October 1 , 1924, one year ago, there were 16 general bonded warehouses, 5 special bonded warehouses, and 57 distillery warehouses, or a total of 78 internal-revenue bonded warehouses containing spirits.

During the past year 2 general bonded warehouses and 22 distillery ware houses, or a total of 24 bonded warehouses , have been discontinued .

The attached table, marked ” A ,” will show these figures more graphically.

There are now remaining 14 general bonded warehouses, 5 special bonded warehouses, and 35 distillery warehouses, or a total of 54 internal-revenue bonded warehouses containing spirits.

Of these 54 warehouses, 29 are concentration warehouses, 6 are consolidated warehouses, 7 are adjacent to industrial alcohol plants, one ( 1 ) is adjacent to an operating fruit distillery , one ( 1) is adjacent to an operating molasses distillery , 6 are in process of concentration, one ( 1 ) is under order to immediately concentrate, one ( 1 ) contains a large stock of immature spirits produced subsequent to the national prohibition act and 2 are warehouses with their concentration status undetermined.

The attached list marked “ B ” lists these warehouses by classes, name, address, and warehouse number, together with their concentration status.

There are approximately 30,000,000 gallons of spirits, according to original gauge, now stored in these warehouses. of this amount approximately 25,000,000 gallons are in the 30 concentration warehouses. Approximately one-half of the remaining 5,000,000 gallons is stored in the six consolidated warehouses . There are attached hereto lists of concentration warehouses, consolidated warehouses, warehouses adjacent to industrial alcohol plants or bonded ware houses, warehouses at operating fruit and molasses distilleries , warehouses in process of concentration and warehouses with concentration status undetermined; also lists of industrial alcohol plants, bonded warehouses and denaturing plants, and statements showing present assignments of officers including warehouse agents and deputy collectors, and estimated number of storekeeper-gaugers and gaugers to be employed during the fiscal year 1927.(Signed ) R. A. HAYNES, Prohibition Commissioner.

It’s clear from this memorandum that the number of concentration warehouses was still being reduced in 1925. The government sanctioned consolidations began in 1922, but it was taking a long time to get it all moved into the approved locations. Lawsuits and logistics made the transition a slow one. Once the country’s whiskey was finding its way to its final storage location, the wheels were set in motion to bottle it all and cease the aging process.

A slowly decreasing supply of medicinal whiskey was becoming problematic, especially for those that would suffer financially by losing access to its “steady supply.” Now that only a handful of wealthy interests were controlling America’s whiskey stocks, there would need to be a push to regain the right to distill whiskey again. The Willis-Campbell Act, a 1921 supplement to the Volstead Act, explained that when medicinal whiskey stocks ran low, the manufacturing of liquor would need to commence in order to fill America’s need. It stated:

“No spirituous liquor shall be imported into the United States, nor shall any permit be granted authorizing the manufacture of any spirituous liquor, save alcohol, until the amount of such liquor now in distilleries or other bonded warehouses shall have been reduced to a quantity that in the opinion of the commissioner will, with liquor that may thereafter be manufactured and imported, be sufficient to supply the current need thereafter for all non-beverage uses…”

In January 1927, the House of Representatives’ Ways and Means Committee held hearings on the subject of medicinal spirits. General Lincoln C. Andrews, Assistant Secretary in charge of Customs, Coast Guard, and Prohibition, testified before the committee. He explained that he met with the following “whiskey owners” whom he “consulted for practical information”:

- Seton Porter, president of Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Co., Louisville, Ky.

- John F. Pell, representing Overholt Distributing Co. , Broad Ford, Pa.

- The following committee: Mr. R. E. Wathen, representing R. E. Wathen & Co. , Louisville , Ky:; Mr. S.D. Peyser, representing Baltimore Distilling Co., Baltimore, Md.; Mr. Frank B. Thompson, representing Glenmore Distilleries Co. , Owensboro, Ky.; Mr. D. K. Weiskopf, representing Jos. S. Finch & Co., Schenley , Pa.; Mr. Emil Schwarzhaupt, representing E. H. Taylor, Jr., & Sons, Frankfort, Ky.

Andrews explained, “The members of this committee, whom I met for the first time on December 19, 1926, stated that they were a voluntary committee, but had talked with representatives of other warehousing firms representing, together with themselves, about one-half the whisky in storage, or about 75 per cent, taken together with the two first named above. They have told me that, as closely as they can estimate, about 45 percent of the total number of gallons in storage is owned by the warehousing firms themselves, and about 55 percent by warehouse certificates in the hands of the public throughout the United States . I have also conferred with Mr. Samuel C. Miller, president of the Frankfort Distillery Co., of Louisville, Ky.”

To be clear, December 19, 1926 may have been the first time General Andrews met with them, but they had been well acquainted with his superior, Robert Haynes, and had been lobbying the Commissioner of Prohibition and Andrew Mellon for years. Mellon was never shy about his belief that the wealthy and well-educated upper class would best serve the country in leadership positions. It is not a stretch to think that Mellon would have believed the wealthiest distillers were the best men to handle any distilling needs the country might have. The Treasury Department certainly favored a select few men within the liquor industry. (If Mellon benefitted personally from their success, so be it!)

Almost immediately after the Ways and Means Committee met and discussed the need to manufacture whiskey to replenish dwindling supplies, a law was proposed in the House to lay out the details of how this manufacturing of new whiskey would take place. It was called the “Medicinal Spirits Act of 1927” or simply the “Hawley Bill” after Representative Willis C. Hawley of Oregon*, chairman of the subcommittee that introduced the measure. The Hawley Bill, which was supported by Secretary Mellon and General Andrews, laid out how “to conserve the revenues from medicinal spirits and provide for the effective Government control of such spirits, to prevent the evasion of taxes, and for other purposes.” It would compel the remaining 30+ concentration warehouses to bottle all remaining medicinal whiskey stocks in glass pints in order to halt the aging process. One of the criteria they had been selected as warehouse sites in the first place was due to their having bottling plants, after all. While all this bottling would take place over the course of 2 years, 6 warehouses sites would be conditioned and refurbished to receive all those neatly packaged cases of whiskey. In other words, the bill wanted all 31 existing concentration warehouses to be further consolidated into only 6 locations. It explained; “By limiting the warehouses as provided in the bill to the proposed number of six, further substantial savings will be effected [sic] in Government expenses, tax evasion will be further decreased, and other economies and more effective supervision of distribution will be brought about through elimination of the various intermediate movements. It is asserted by the Treasury Department that economies in administrative costs can be effected [sic] to the extent of at least $1,000,000 a year.” The bill would also eliminate all existing wholesale medicinal whiskey distribution. The only legal transactions of medicinal whiskey would take place directly between concentration warehousemen and retail druggists. (Druggists with government permits were the only legal seller of medicinal whiskey to the public.) Severe penalties were included to discourage label and trademark counterfeiting and stop the adulteration of barrels from taking place. Advocates for the bill blamed the adulteration of barrels on the wholesale (middleman) locations and on handlers of the whiskey while in transit before being sold to pharmacies and hospitals. It was far more likely that the adulteration (emptying of barrels or adding water to the barrels) was taking place within the warehouses themselves or had been taking place before being transported to the concentration warehouses to begin with, but that was not helpful for the overall narrative. The Hawley Bill was designed to place the country’s whiskey into the hands of only a few men and exclude anyone that might get in the way of accomplishing that end.

The Hawley Bill passed the House vote 209 to 151. It received bipartisan support from both the “wets” and the “drys.” To the “wets” it meant government sanctioned distilling which would bring down the cost of medicinal whiskey to pre-prohibition prices. To the “drys” it meant putting an end to bootlegging and illegal counterfeiting. The Senate, however, killed the House’s bill. There had been another bill proposed that called for the government to create its own distilling operation in order to satisfy the Willis-Campbell Act’s provision for more whiskey to be made when medicinal whiskey supplies ran low. That bill was shot down because it was essentially creating a government monopoly and putting the government into the whiskey-making business. The Hawley Act was opposed for similar reasons. Democratic Representative Howard from Nebraska suggested an amendment to change the title of the bill from “The Medicinal Spirits Act of 1927” to “an act for the relief of Andrew Mellon and associates.” Many believed that Mellon was still in league with the distillers and warehousemen, especially because he had been a distillery owner himself. He was considered a “wet” and had never been a supporter of the temperance movement. The point had been made during deliberations over the Hawley Bill in the House that the Commissioner of Prohibition and the Secretary of Treasury already possessed the power to do most of what the bill was calling for and some questioned its purpose in the first place.

A number of important things happened in the months after the Hawley Act failed in the Senate.

- On April 1, 1927, the Prohibition Bureau, which had been under the auspices of the Department of Internal Revenue and led by the Commissioner of Prohibition and the Secretary of the Treasury, became an independent entity within the Department of the Treasury. The Secretary of the Treasury, which had been Andrew Mellon since 1921, would now oversee the entire department.

- In May 1927, Roy Asa Haynes, Acting Commissioner of Prohibition, who was well-liked by the Anti-Saloon League for his tough stance on Prohibition violators, was replaced by Dr. James M. Doran as full-fledged Commissioner.

- The company known as the American Spirits Manufacturing Company, which was the corporate face of the restructured Whiskey Trust, purchased the assets of 5 major concentration warehouse locations: R.E.Wathen & Co., Hill & Hill Distilling Co., F.S. Ashbrook Distilling Co., E.H. Taylor & Sons and the Baltimore Distilling Company. Already in possession of the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company’s concentration warehouses at Elk Run (the largest of the consolidation warehouse sites with approx. 60,000 barrels, twice as much as other locations), they now controlled most of the whiskey in Kentucky. The American Spirits Manufacturing Company consolidated their expansive holdings and restructured itself under a new name…the American Medicinal Spirits Company. The American Medicinal Spirits Company now controlled half of the whiskey stocks in Kentucky and nearly 30% of the total whiskey in the United States.

Remember those companies that were being consulted by the chief Prohibition officer, Gen. Lincoln Andrews, for “practical information” by the Treasury Department in January? Almost all those companies were given priority attention as the Treasury Department used its powerful role to move forward with plans to distill medicinal whiskey anyway- without a Senate approved bill. They were not able to concentrate all the whiskey in the country into only 6 locations as the plan had been in the Hawley Bill, but most other aspects of the law were put in motion by the Treasury Department. (Ever wonder why all the bottles of pre-prohibition medicinal whiskey pint bottles’ tax stamps show the bottling date as being in 1927? The 31 concentration warehouses were made to bottle what remained of their barrel stocks to halt further aging that year.) While a good show was made to ask for applicants for permits to distill new medicinal whiskey, the choices had already been made.

Whiskey stocks were slowly dwindling as legal medicinal trade depleted the government’s stores by 1,500,000- 2 million gallons per year. By the summer of 1929, it was estimated that the amount of medicinal whiskey remaining was approximately 9 million gallons or 5 years’ worth of supply. The new Prohibition Commissioner, Dr. James M. Doran, revealed to the papers that he would license 6 distilleries to produce 2 million gallons of rye and bourbon. That amount, after 4 years of aging, would add one year’s medicinal whiskey supply to existing stocks.** Outspoken members of Congress protested the need to produce any new whiskey. Senator Elmer Thomas of Oklahoma declared, “there is no need for medicinal whiskey.” He stressed that “No one has advanced any sound reason for the necessity of medicinal liquor. Alcohol is the base of whiskey, and it can be used for medicinal purpose camouflaged in some form other than whiskey if it is necessary to use it internally.” The Senator did have a point! Why was it necessary to make bourbon and rye whiskey instead of gin or rock-and-rye or any other spirit? Could it have been that those particular products were the most valuable of all the distilled spirits?- especially to those few companies that stood to profit from the Secretary of Treasury’s decisions? Either way, Dr. Doran announced in June 1929 that 1,300,000 gallons of bourbon and 700,000 gallons of rye would be produced by 6 companies. This number, however, was not the final count of active distilleries. The number would grow when the permits were actually distributed later that year.

Without missing a beat, the American Medicinal Spirits Company (AMSC) began to stack the deck. In October 1929, The AMSC incorporated 17 distillery companies to be based in Louisville. This did not mean they meant to reopen any distillery facilities. What it meant was that they would use the company names on labels of bottles filled from barrels within their concentration warehouses. (The practice of incorporating defunct distillery names “for bottling purposes only” is often done today, but this was the first time it was done on this scale in the past.)

The American Medicinal Spirits Company’s newly incorporated names were:

- The Green River Distillery Company

- The Hermitage Distillery Company

- The Gwynnbrook Distillery Company

- The Chicken Cock Distillery Company

- The Bond and Lilliard Company

- The Black Gold Distilling Company

- The Medical Arts Distillery Company

- The Mount Vernon Distillery Company

- The Old Crow Distillery Company

- The Old Grand Dad Distillery Company

- The Old McBrayer Distillery Company

- The Old Taylor Distillery

- The Pebbleford Distillery Company

- The Spring Garden Distillery Company

- The Federal Distillery Company

- The Sunnybrook Products Company

While Kentucky bourbon interests were slated to produce 1.3 million gallons of bourbon, The AMSC was given priority by the Treasury Department to produce 60% of that amount. In November 1929, Democratic Representative Cellar of New York wrote to Dr. Doran:

“The American Medicinal Spirits Company has already sought mastery over the entire whisky distilling and warehousing industry. It now practically controls, through its plants and warehouses about 50 per cent of all the medicinal whisky in bonded and free warehouses.

“By giving it 60 per cent of all the bourbon whisky to be manufactured, I believe you are fostering their stranglehold upon medicinal whisky. This concern already controls the prices of whisky sold to retail and wholesale druggists.

“Is it not wrong to help this corporation fasten itself upon the country as a monopoly? In the event of any epidemic like the ‘flu’ the health of the nation would be jeopardized, as whisky is an important agent in combatting this dreadful disease. Nevertheless, in such a crisis, the company could charge any price it saw fit for this whisky. No one could compete against it.

“I earnestly urge that you investigate the operations of this company before you make these allotments final.”

“This organization already comprises the following formidable array of distilleries, warehouses and companies: F.S.Ashbrook Distillery Company, Baltimore Distilling Company, Clear Springs Distilling Company, Daviess County Distilling Company, Hill & Hill Distilling Company, Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company, Old Grand Dad Distillery Company, Peerless Distillery Corporation, Sunnybrook Distillery Company, E.H.Taylor, Jr. & Sons, R.E.Wathen & Co., Schwarzbaubt & Co., King Trading Company, American Distilling Company.”

Cellar did not argue against distilling new whiskey. He believed it was necessary to replenish the nation’s supply of medicinal whiskey. He only questioned the way the allocation was handled. He explained;

“…information has reached me that allotments permitting distillation of Bourbon whiskey to be manufactured have been made by you to some six Bourbon distilleries as follows: American Medicinal Spirits Company, 859,600 gallons; Brown-Forman Distilling Company, 105,000; Pepper Distilling Company, 37,000; Frankfort Distilling Company, 203,200; Stitzel Distilling Company, 65,000; Glenmore Distilling Company, 128,000; total 1,397,800 gallons.”

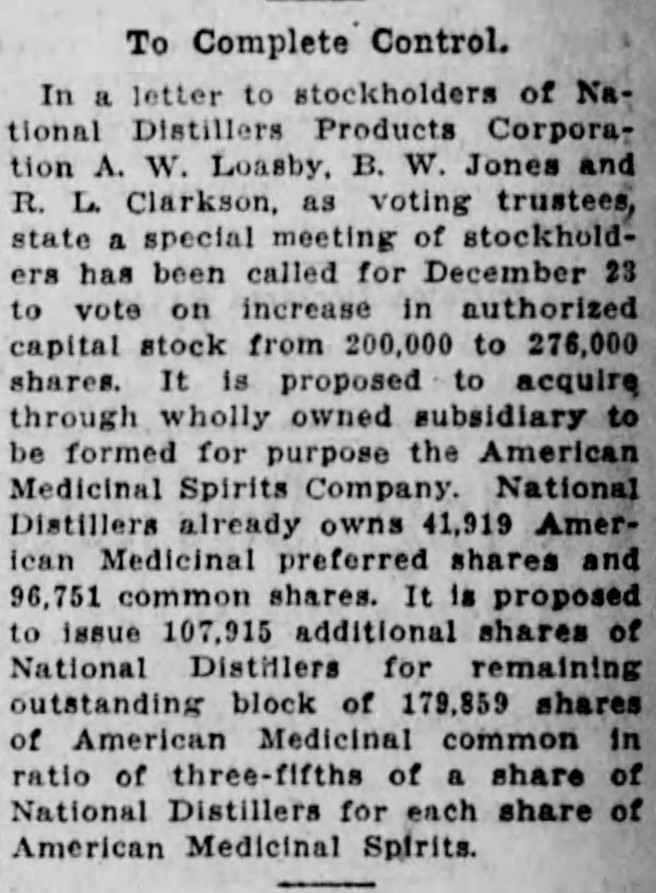

The protests would not phase the Treasury Department. Doran insisted that the distilleries were chosen because they were the only facilities in the United States that remained in condition to supply the government’s requirements. He neglected to add that the reason they were in that condition is because they had spent the last 2 years prepping for the opportunity. In December 1929, the American Medicinal Spirits Company was absorbed by National Distillers Products Corporation. National Distillers had already been a major shareholder of AMSC, but now it controlled the company.

Andrew Mellon remained under fire for being a “wet” and for having family associations with the liquor industry. No matter how often he protested and explained that he had divested from his connections to the industry, the newspapers repeatedly called out his favoritism and cronyism. There is little doubt based upon the treasury department’s final choices for distilling permit recipients that favoritism was involved. The first distilleries to begin production in November 1929 were the American Medicinal Spirits Company properties (in Louisville, Kentucky and in Baltimore, Maryland) and the Overholt Distillery in Broad Ford (or “ the Mellon Distillery” as it was nicknamed by newspapermen). The others would begin operations in January 1930. They would all have fully-aged medicinal whiskey by 1934.

The rye distilleries given permits to make medicinal whiskey were:

- Overholt Distillery at Broad Ford, Pa. (still owned in 1929 by David Shulte’s Park & Tilford)***

- Joseph S. Finch Co. (aka Schenley Distillery) now located in Schenley, Pa.****

- The Large Distillery in West Elizabeth, Pa (would be purchased by Overholt in August 1930)

- Baltimore Distilling Company (owned by American Medicinal Spirits Company)

The bourbon distilleries given permits to make medicinal whiskey were:

- Bernheim Distillery in Louisville, Ky. (owned by American Medicinal Spirits Company)

- A.Ph. Stitzel Distillery in Louisville, Ky.

- Lee Redmon Company in Louisville, Ky. (owned by Brown-Forman Distilling Company)

- Glenmore Distilling Co. in Owensboro, Ky.

- James E. Pepper Distillery Company in Lexington, Ky.

- Frankfort Distillery in Frankfort, Ky.

- George T. Stagg Distillery in Frankfort, Ky

There were also 20 fruit distilleries given permits that were operating to produce over 800,000 gallons of fruit spirits. These brandies were used for both medicinal use (about 100,000 gallons) and for the fortification of wines and for non-beverage purposes. Industrial alcohol was being produced in much greater quantities- over 165 million gallons each year.

In the years before Repeal, 1931 and 1932, the same permits were distributed. The allotment of whiskey to be laid down, however, grew from 2 million to 2,728,000. Dr. Doran explained that the amount would increase to take advantage of the low price of grain and the number of unemployed distillery workers. J.E.Pepper Distillery, though offered a permit again in 1931, bowed out preferring to receive their allotted whiskey from a larger producer.

The Stitzel Distillery consumed about 430 bushels of grain to produce their 40 barrels a day while the AMSC consumed approximately 1,650 bushels to make 165 barrels a day. About 350,000 bushels of grain were consumed each year by Kentucky distilleries making bourbon alone. For those bourbon producers, the corn was brought in from Illinois and Iowa, the rye from Minnesota, and the barley malt from Wisconsin. They all worked for about 3 months out of the year to fill their orders. Each morning, farmers would line up their trucks at the distilleries’ doors to make use of the spent grains and to fill up tanks or barrels with all the water they could haul.

The distilleries going back into production spelled the end of Prohibition. Impeachment charges were filed against Andrew Mellon in February 1932, but he resigned from the office. Herbert Hoover appointed Ogden Mills to fill his shoes. By December 1932, a Resolution to Repeal the 18th amendment with the 21st amendment was approved by Congress. On December 5, 1933, the ratification of the 21st amendment put an end to it all. The distilling industry as it existed before Prohibition was gone. The new industry that would built on its bones was wholly different and shared very little in common with its predecessor. Prohibition had ensured that only a handful of men were in control. It was a brave new distilling world and nothing would ever be the same.

*Hawley was one of the authors of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Bill which is largely blamed for causing the Great Depression in 1929.

**Notice here, neither the quality or style of whiskey made by these 6 distilleries is considered at all. While the concentration warehouses were full of aged whiskey from all over the country and from hundreds of distilleries with wide variations in flavor and production styles, the nation’s medicinal whiskey would now be limited to the production of only a handful of bourbon distilleries and several rye whiskey distilleries. This is the first time that the nation’s whiskey would lose its wide variation in distinct flavor profiles.

*** Initially, the distilleries chosen to distill in Pennsylvania were Large Distillery and Overholt. Both were independently owned in 1929, but Large Distillery was sold to Overholt Distributing Co. in 1930, which was owned by David Shulte’s Park & Tilford Co.

****Joseph S. Finch’s historic distillery was located in Pittsburgh until it was purchased by Schenley during Prohibition to gain control of its rye whiskey stocks and its concentration warehouse permit. The name “Joseph S. Finch” and all its assets were transplanted onto Schenley’s plant in Schenley, Pa. The historic plant in Pittsburgh would be abandoned in favor of Schenley’s location.