Once the US government began implementing liquor taxes to pay for the war, Philadelphia became home to many privately-owned consolidation warehouses where liquor firms could store their goods, in bond and under government supervision. These warehouses were concentrated along the riverfront where the major liquor houses kept their own warehouses, storefronts, and offices. A major fire in August 1869 consumed all nine of Colonel William C. Patterson’s privately-owned warehouses along the waterfront where many of Philadelphia’s most respected liquor men kept their stocks of whiskey. While the warehouses were advertised as being “fire-proof”, over 25,000 barrels of whiskey were lost in one night. Carstairs & McCall were among the firms that lost hundreds (several firms lost thousands) of barrels in that fire, but the company was well insured, and they were able to emerge from the tragedy relatively unscathed. James Carstairs, Sr. passed away in 1875, but his son would very capably guide the business into the future.

It’s important to clarify that the whiskey sold by Carstairs & McCall was not their own. For more than half a century, as the family built its empire in Philadelphia, they did so through the sale of spirits manufactured by many different manufacturers. They sold both domestic and imported liquors. One might think of them as a specialty shop for discerning consumers![]() Essentially, they were a liquor firm that sold specialized goods to customers that trusted their reputation for handling only the highest quality products. They held contracts with several distilleries that sold them bulk whiskey. That whiskey was then stored in warehouses under their own name- because once they purchased it, it was their whiskey, after all. They were known as a liquor wholesaler- similar to what many refer to as an NDP, or non-distiller producer, today. What made them (and every other pre-Pro liquor wholesaler) different was that they handled their own distribution and kept offices and warehouses in several major US cities- not just Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, but in Massachusetts, New York, Florida, and Maryland, as well. Their business was not particularly unique- their business model was similar to many other liquor firms in the United States. What set them apart was their level of success, their respect within the trade, and the half century of experience that they could boast within the industry. There was no three-tiered system or “middleman” before Prohibition, so Carstairs & McCall were able to build their own distribution network and advertise their own products to the public. They built their own brand identities, and through them, their own legacy.

Essentially, they were a liquor firm that sold specialized goods to customers that trusted their reputation for handling only the highest quality products. They held contracts with several distilleries that sold them bulk whiskey. That whiskey was then stored in warehouses under their own name- because once they purchased it, it was their whiskey, after all. They were known as a liquor wholesaler- similar to what many refer to as an NDP, or non-distiller producer, today. What made them (and every other pre-Pro liquor wholesaler) different was that they handled their own distribution and kept offices and warehouses in several major US cities- not just Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, but in Massachusetts, New York, Florida, and Maryland, as well. Their business was not particularly unique- their business model was similar to many other liquor firms in the United States. What set them apart was their level of success, their respect within the trade, and the half century of experience that they could boast within the industry. There was no three-tiered system or “middleman” before Prohibition, so Carstairs & McCall were able to build their own distribution network and advertise their own products to the public. They built their own brand identities, and through them, their own legacy.

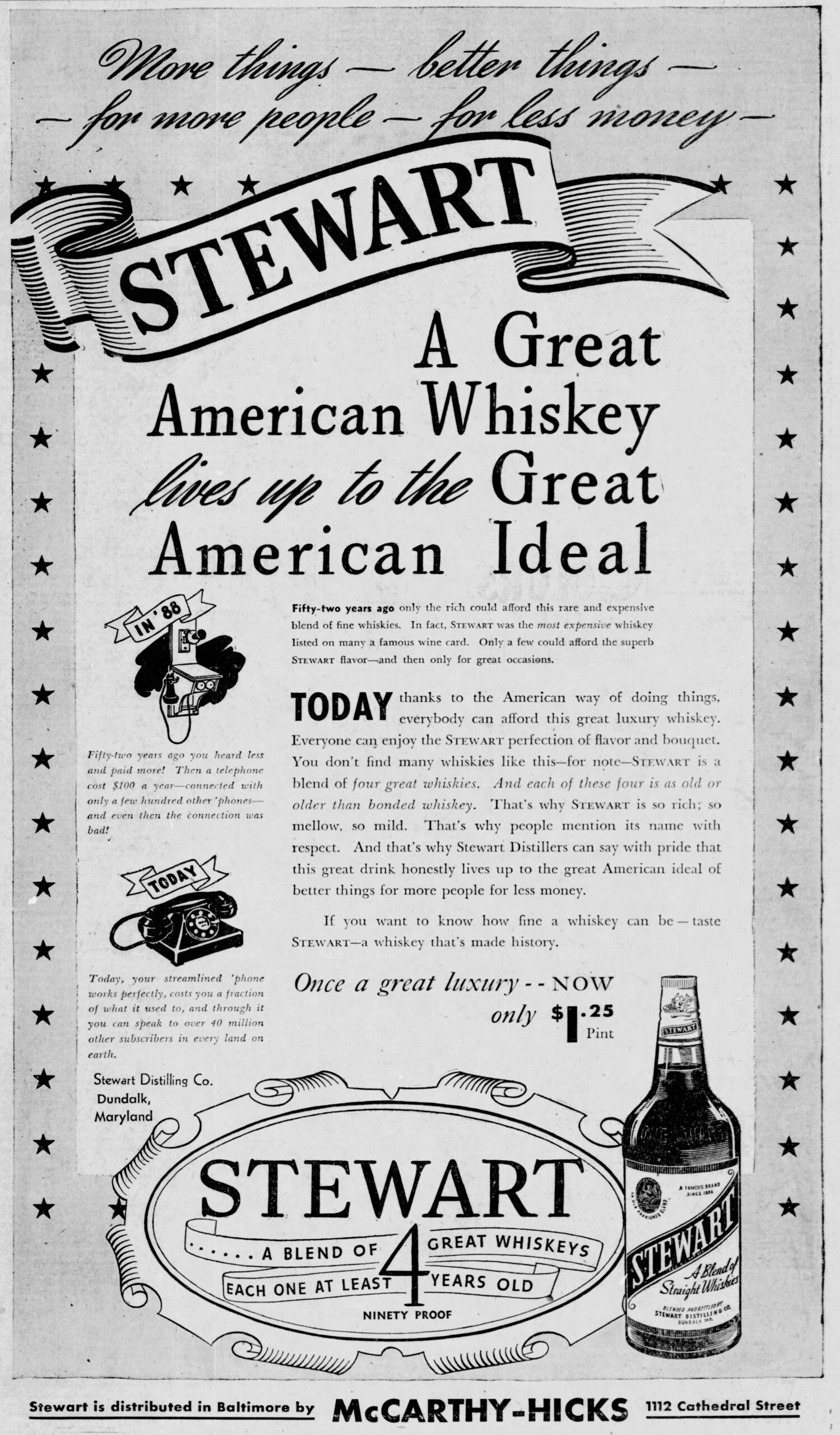

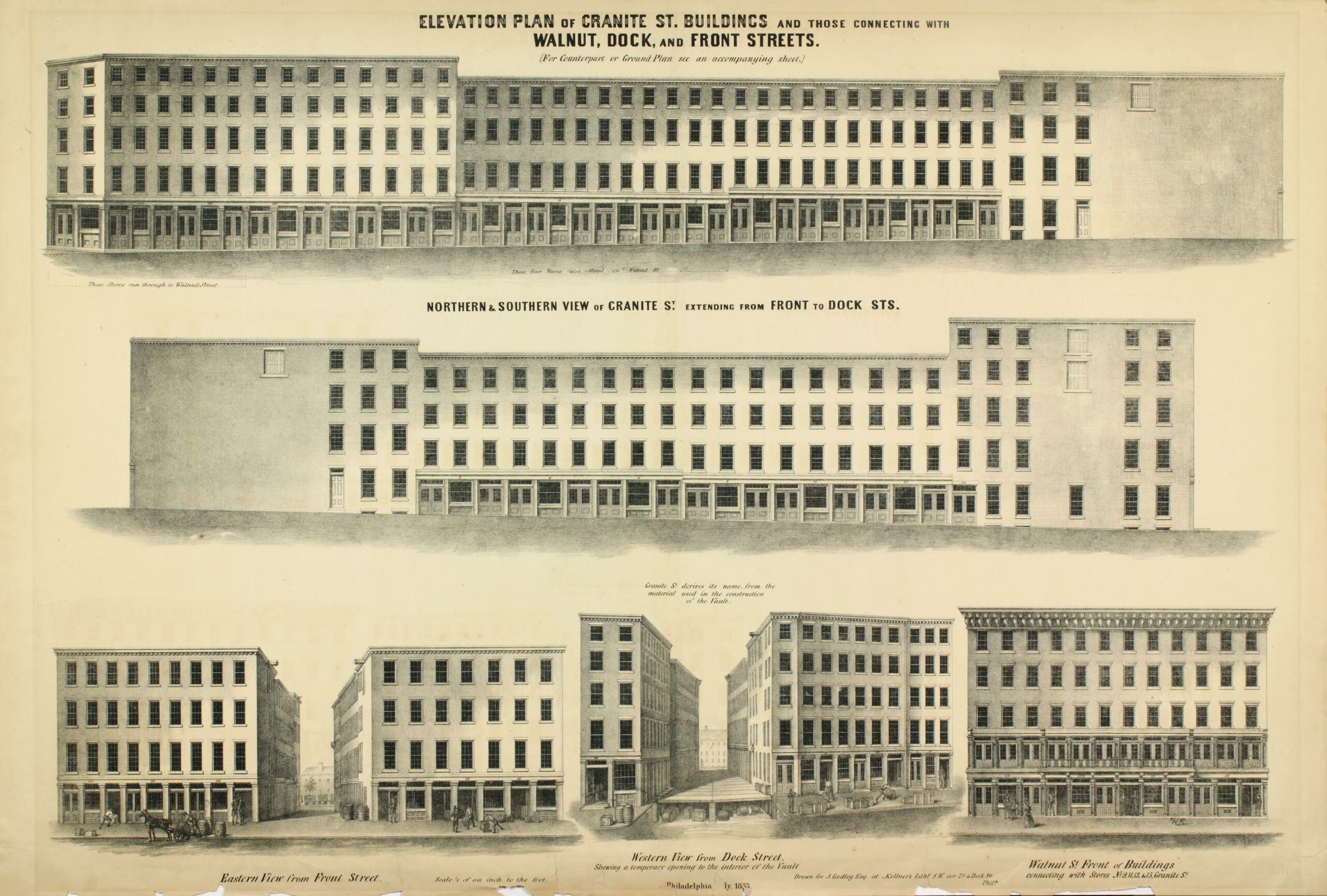

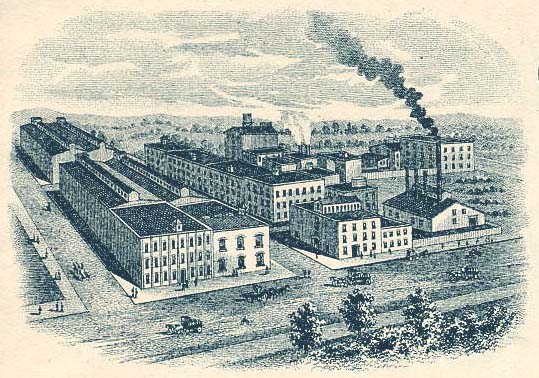

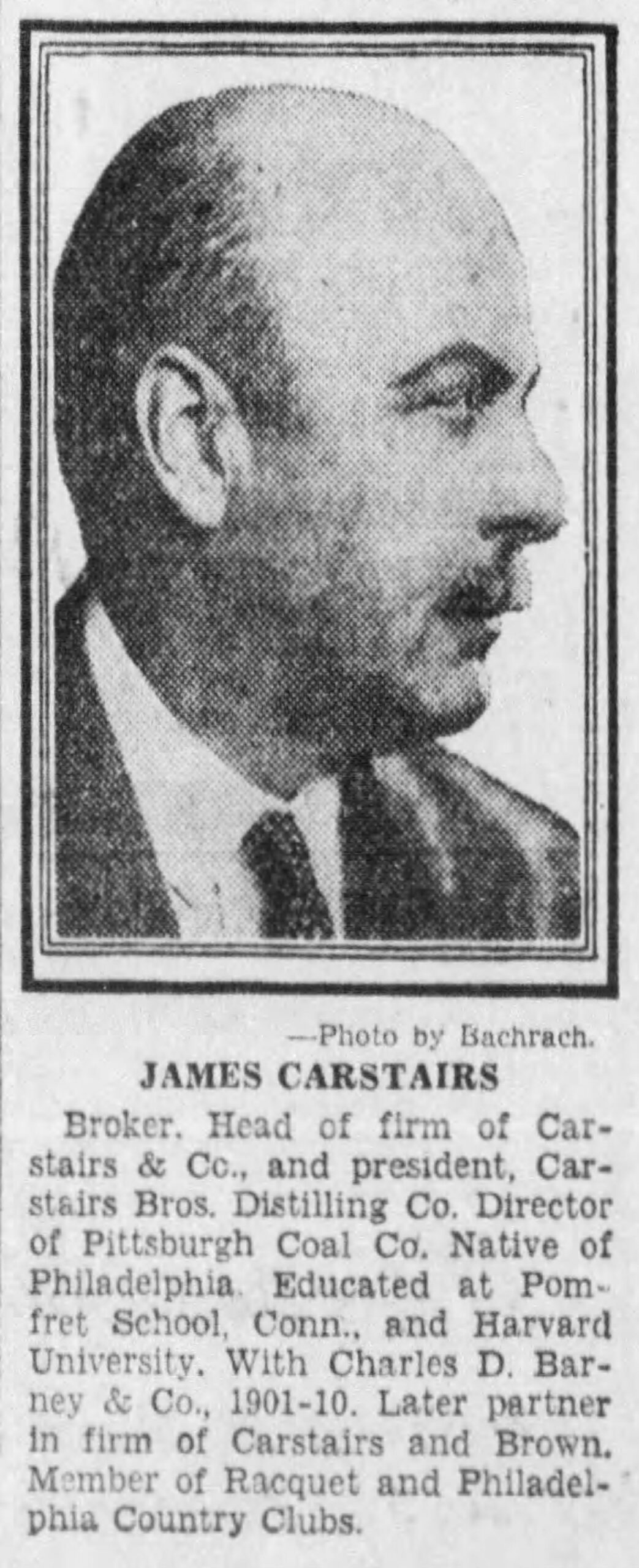

By 1879, Carstairs & McCall had outgrown their Delaware Avenue address and upgraded to a larger property at 222 Front Street and 139 Dock Street. Their expansion led to the establishment of offices in both New York and Boston. James Carstairs, Jr. brought his own sons, Daniel H. and John Haseltine Carstairs, into the firm in 1886, at which point they had become the largest wholesale liquor firm in Philadelphia. James Carstairs Jr. died in 1893, and his partner, John McCall, followed him soon after in 1894, but James Jr.’s sons secured the future of the firm by purchasing the Robert Stewart Distilling Company in Highlandtown, Maryland in 1897. During this time, the Whiskey Trust had been making it difficult for old firms like Carstairs to secure the whiskey they had come to rely on from their trusted sources. The trust was buying up so many of America’s whiskey manufacturers that owning a distillery had become a necessity for any firm not wanting to fall prey to the whims and pricing schemes of the trust. Stewart Distilling Co. had been supplying whiskey to many other firms, perhaps most notably H.B.Kirk & Co. in New York, with rye whiskey for their private bottlings (Old Crow Rye, for instance, was likely sourced from this distillery). James Carstairs Jr.’s purchase of the Stewart Distillery would now put Carstairs & McCall Co. in control of its own output and keep them flush with whiskey from at least one of their trusted suppliers. Carstairs of Philadelphia’s core brand would now become Stewart Pure Rye Whiskey, a Maryland-produced rye whiskey. Production at the plant in the early 1900s was approximately 15,000 barrels per year. This business move was a smart one, and by September 1904, the company’s growth saw them upgrading their office headquarters again, this time to 254-256 South Third Street. By 1908, the firm employed nearly 100 employees at its Philadelphia, Boston, New York, and Maryland locations.

It was a high-end product, served in all the major city’s finest clubs. One of their mottos for their non-refillable bottle was “A good bottle to keep good whiskey good.” Maybe not the most inspired tag line, but it got the point across. As the First World War began and the need for supplies and ammunition to be exported to Europe was increasing, the Stewart Distilling Company saw an opportunity. In 1915, the Carstairs brothers purchased 20 acres along the Delaware River front. The property had been home to a war munitions plant. Their plan was to expand capacity and employ 400-500 men in the production of industrial alcohol and powder munitions for export. By 1919, however, the Philadelphia-based company was filing for dissolution. The impact of the war and the closure of all US distilleries put the Carstairs at a huge disadvantage. J.H. Carstairs secured his distilling plant in Highlandtown, Maryland by purchasing it outright. He had a mind to maintain it as a concentration warehouse for the government but was unable to secure the permits to do so. He would bide his time instead.

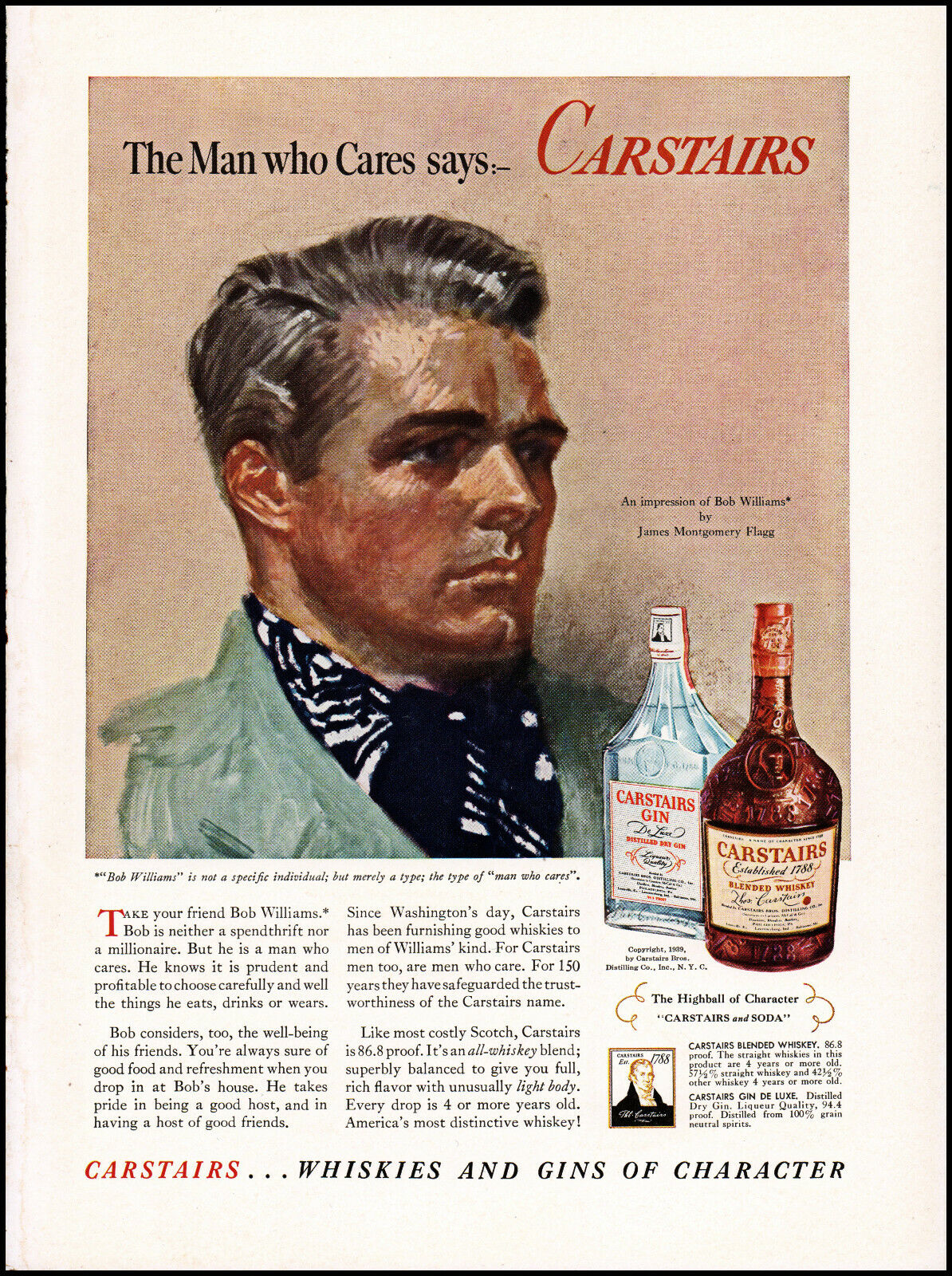

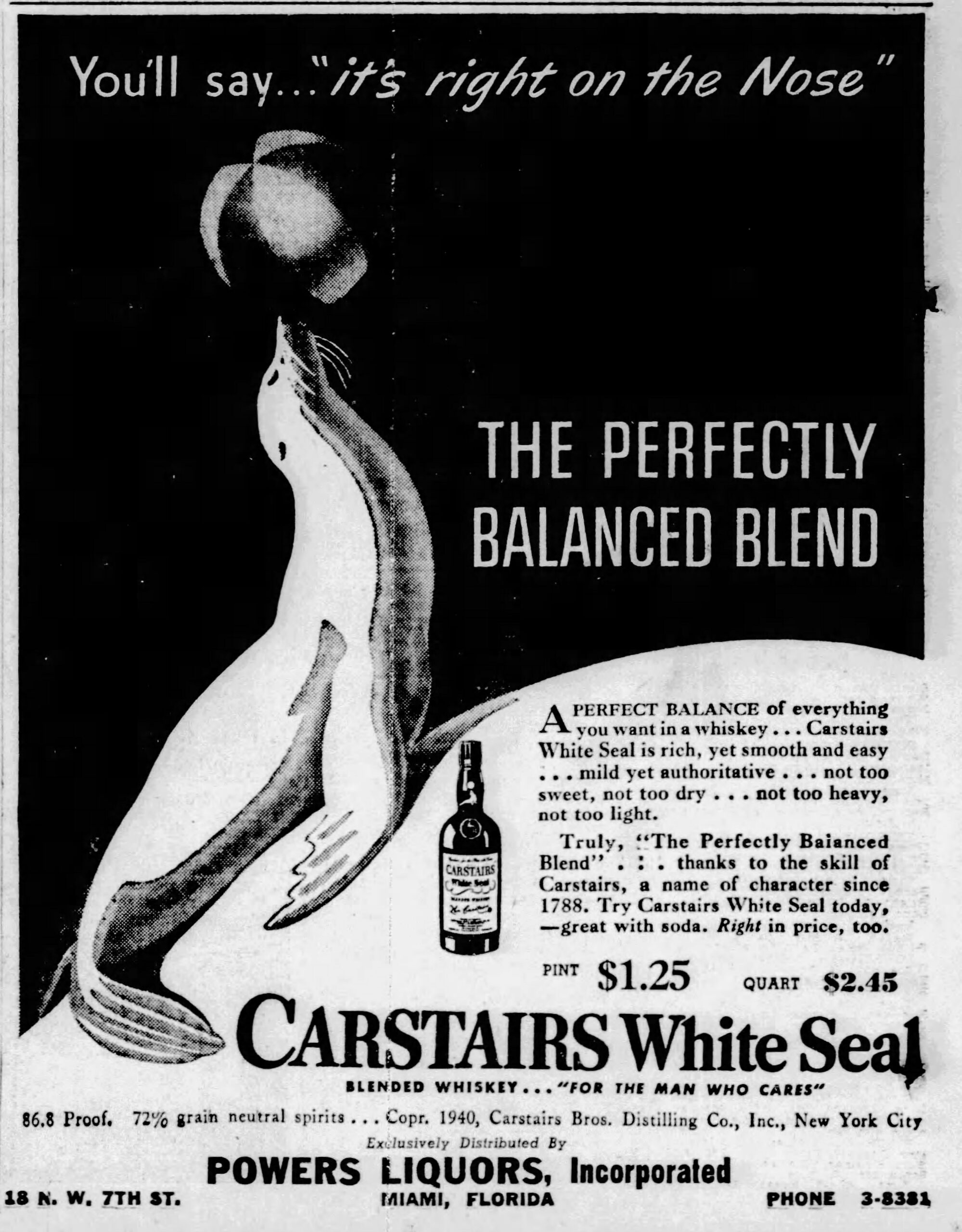

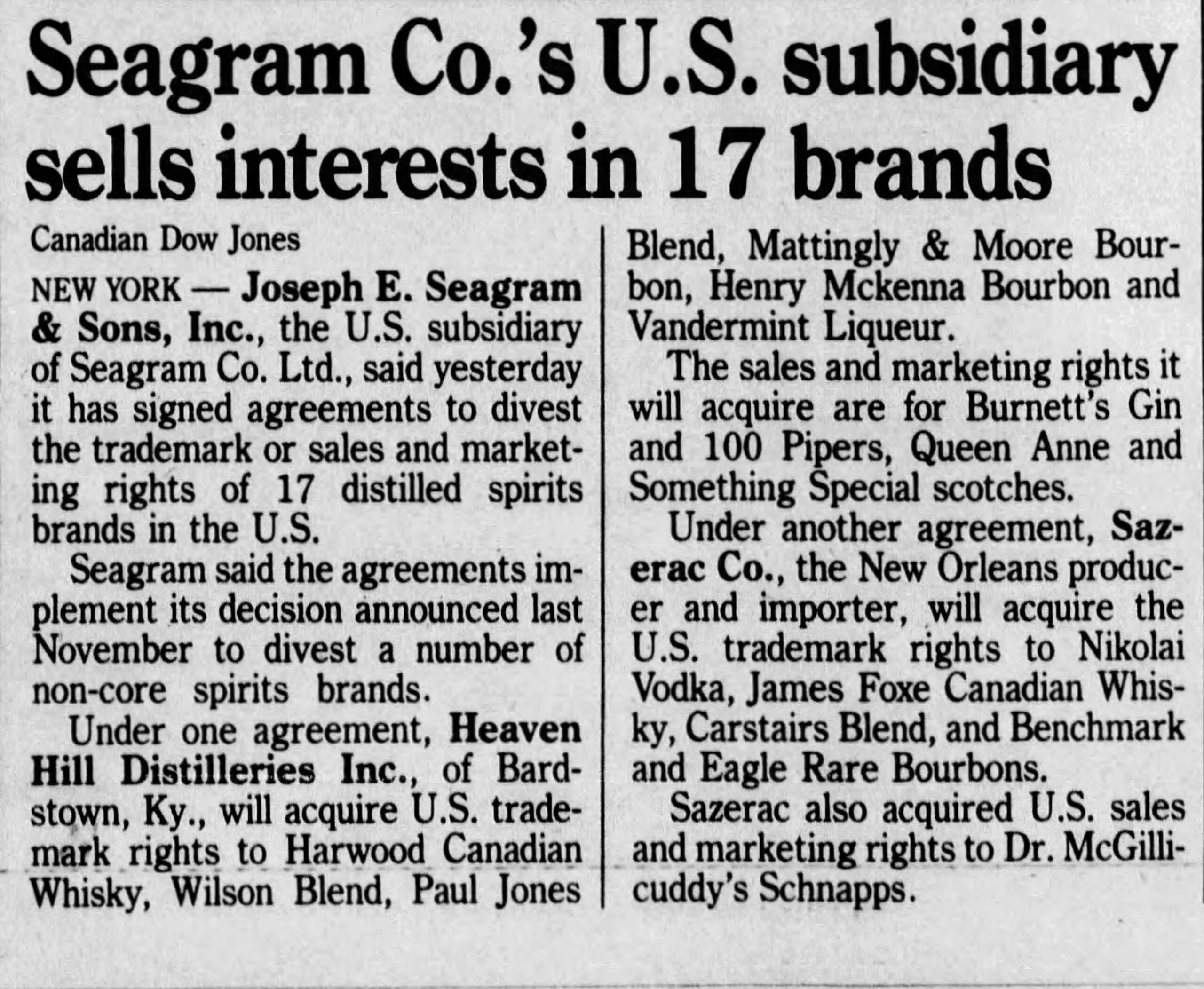

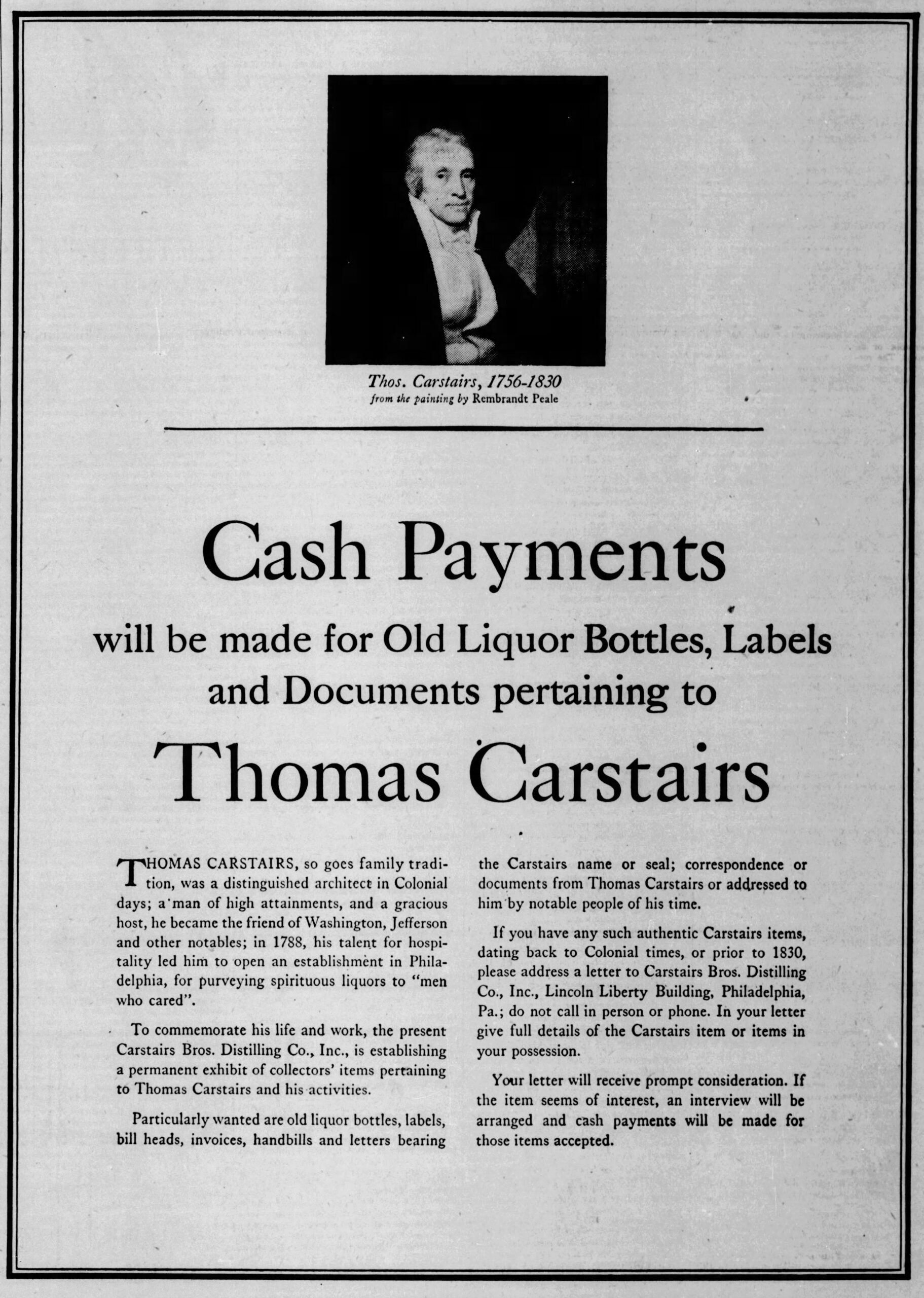

Beneath a small, etched print of a painting of Thomas Carstairs by Rembrandt Peale, the ads read: “Cash Payments will be made to locate old liquor bottles, Labels and Documents pertaining to Thomas Carstairs.” It seems the “founded in 1788” claim by the brand owners was highly prized and they wanted more substantial proof to build an exhibit in his honor. While I don’t doubt that James Carstairs III valued his family’s history and the integrity of his family’s brand, it seems that Seagram’s was not as keen. It took only 2 more years for the company to turn what they claimed to be a 152-year-old brand into a cheap whiskey blended with 72% neutral grain spirits. Carstairs White Seal Blended Whiskey was introduced in 1940 and the brand would never be the same. Nor would it ever regain its respectability. It’s almost too appropriate that they chose a seal balancing a ball on its nose to represent the new blend because they took a majestic, well-adapted, valuable brand and turn it into a circus act. A proud, respected brand born out of one of the oldest whiskey producing cities in the nation was laid low to extract every last dime that could be squeezed out of it. Way to go, Seagram’s!

Beneath a small, etched print of a painting of Thomas Carstairs by Rembrandt Peale, the ads read: “Cash Payments will be made to locate old liquor bottles, Labels and Documents pertaining to Thomas Carstairs.” It seems the “founded in 1788” claim by the brand owners was highly prized and they wanted more substantial proof to build an exhibit in his honor. While I don’t doubt that James Carstairs III valued his family’s history and the integrity of his family’s brand, it seems that Seagram’s was not as keen. It took only 2 more years for the company to turn what they claimed to be a 152-year-old brand into a cheap whiskey blended with 72% neutral grain spirits. Carstairs White Seal Blended Whiskey was introduced in 1940 and the brand would never be the same. Nor would it ever regain its respectability. It’s almost too appropriate that they chose a seal balancing a ball on its nose to represent the new blend because they took a majestic, well-adapted, valuable brand and turn it into a circus act. A proud, respected brand born out of one of the oldest whiskey producing cities in the nation was laid low to extract every last dime that could be squeezed out of it. Way to go, Seagram’s!