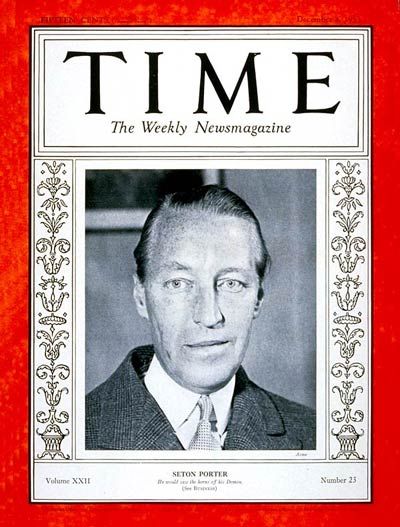

Influential Men in Whiskey- Seton Porter (Intro)

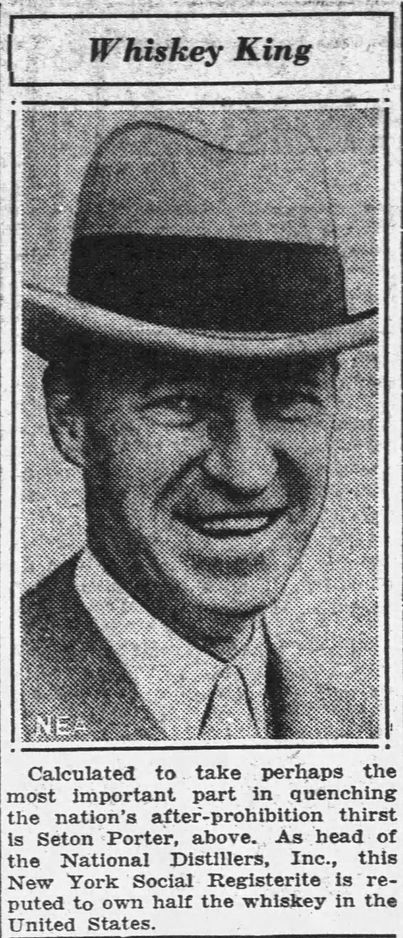

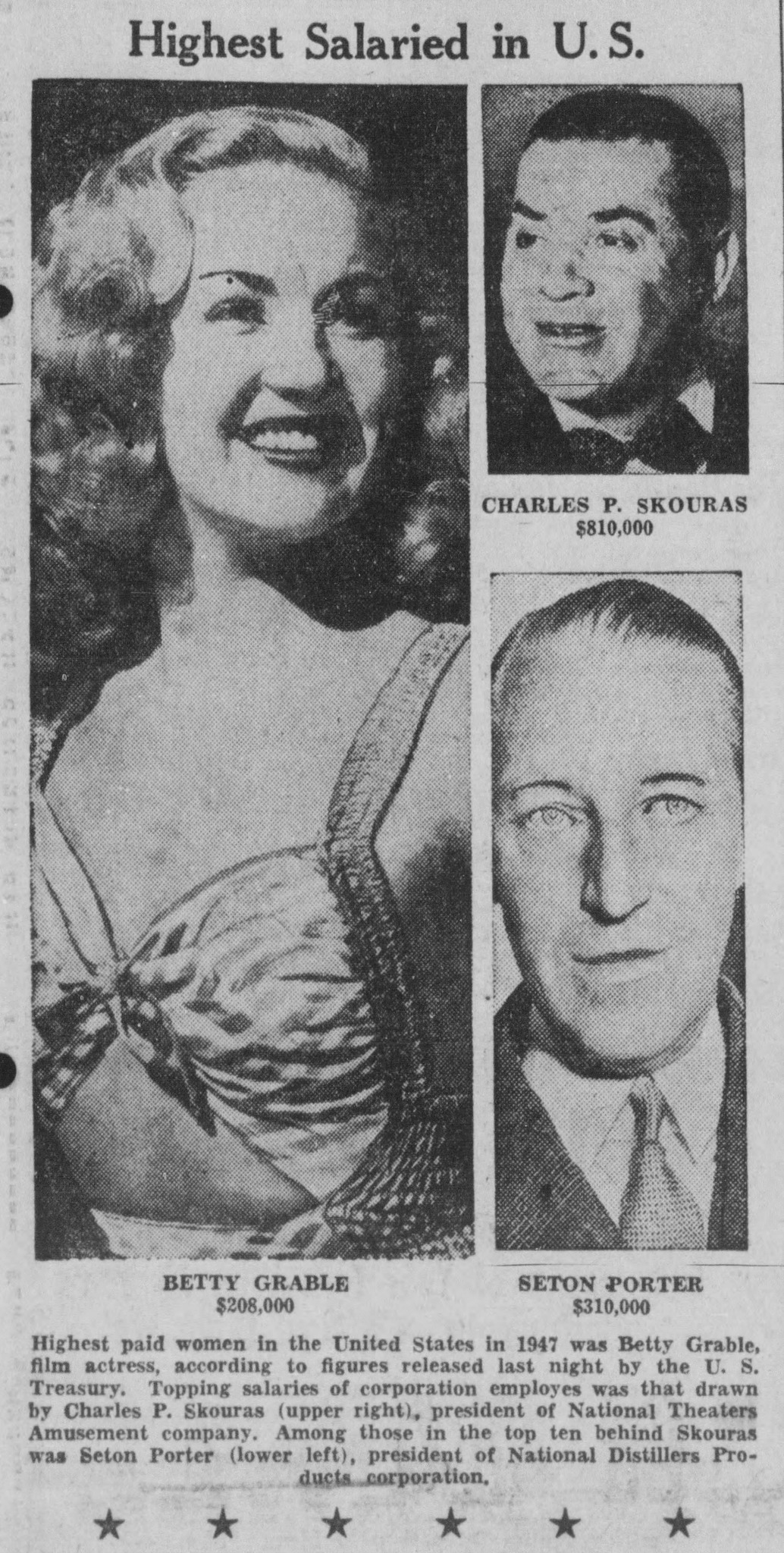

Seton Porter is one of those iconic figures that can not be ignored in American whiskey history. He was so influential that it’s difficult to sum him up! It’s easy to say that he was the man behind National Distillers’ Product Corporation, which owned nearly 80% of America’s whiskey stocks after Repeal. But owning nearly all the liquor in the United States and having all the connections necessary to sell it wasn’t enough for National Distillers. Perhaps the most impressive accomplishment by Seton Porter and his National Distillers was the cultural shift Porter was able to achieve in making liquor a socially acceptable product to purchase and a financially respectable product to sell after 13 years of its being considered illegal contraband. Whiskey, specifically, had been a pariah since Prohibition, but National Distillers spent a great deal of money marketing their whiskeys as a wholesome, natural part of the family experience- or at least part of “the man of the household’s” experience. Seton Porter was a superstar! He branched his empire into fuel and chemicals, but his laser focus toward maintaining his company’s domination over the US and Canadian whiskey industry made him arguably the most influential man in American whiskey history after Repeal in 1933. Even in the years before his death in 1953, he was crafting the whiskey industry to suit his own ends.

Part 1

(written 1/7/24)

The whiskey industry had been turned on its head after Repeal (1933). In all the uncertainly, one man had positioned himself to profit from the chaos. That man was the president of National Distillers, Seton Porter. Porter is often described as a “miracle worker” and the “savior of U.S Food Products Corporation.” But, in truth, Porter was not working miracles. He was gaming the system, and had done so quite capably. Seton Porter, with the support of many powerful men, was able to become the most powerful man in the American whiskey trade after Prohibition. He did so with the help of some very unscrupulous characters and through the use of his own great personal wealth.

Seton Porter’s biography has never been written about, which I find odd considering how important his contributions to American whiskey have been. It is quite shocking to me that no one has tackled this incredibly interesting person’s life. He has had more influence on the modern whiskey industry than perhaps any other person, yet he’s practically a footnote in American whiskey history. Of course, not all of his dealings were above board, and the truth of how he changed the industry would likely upend what a lot of people believe to be true.

Seton Porter was the product of the Gilded Age, but he was late to “the game”. His historic legacy as it related the American whiskey has been white-washed. Even his obituary eliminates his close ties to the oil and railroad industries. (This was most likely due to the proximity of his business dealings to the infamous Teapot Dome Scandal and his desire to keep his ties to American oil quiet.) He is always described as a talented engineer that dabbled in a few things before almost falling into the role of running the largest liquor company the world had ever seen. I assure you, that was not the case. Seton Porter was a man driven by the ambition to have it all…and he was quite successful! He did so by taking vertical integration to new levels and by making all the “right” friends that could help him achieve his ends. I’ll write this introduction to Seton Porter in a few parts- today, we’ll look at Seton’s early years. (Unfortunately, I could find no images that might help illustrate this period of time.)

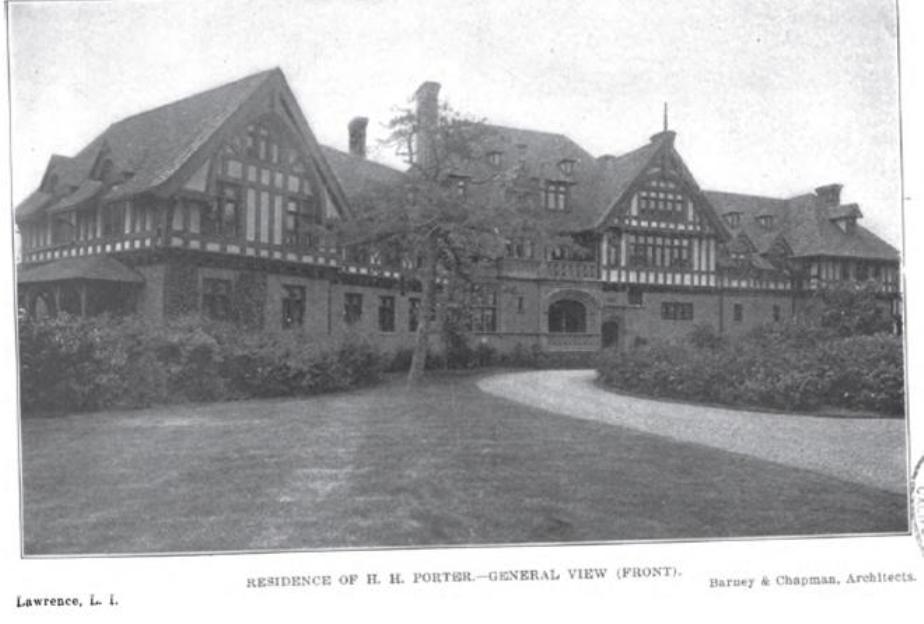

Seton Porter was born on July 8, 1882. He was the child of Henry Hobart Porter and Anna Metcalf Dwight Porter. The Porters owned the largest house on Washington Square in New York City. Henry H. Porter, Sr. was New York’s commissioner of charities and corrections from 1881-1896 and was close friends with the governor, Samuel J. Tilden. Henry Porter’s sister, as it happens, was an Italian countess! On one of his visits to her, Victor Emanuele II bestowed upon Henry the Italian Order of St. Maurice and St. Lazare. These was a very connected New York couple, and they bought their children the best educations money could buy. Like their wealthy parents, both Seton and his older brother, Hobart, would go on to be very successful. Hobart was 17 years older than his younger brother, so he experienced his business success during the Gilded Age in New York City. After the deaths of their parents (Anne in 1894 and Henry in 1904), Hobart would take Seton under his wing.

Hobart Porter was born on March 12, 1865. He was a graduate of Columbia University School of Mines, an engineering school in New York City. Porter, along with E.N. Sanderson, founded the engineering firm of Sanderson & Porter in 1894. Through his engineering firm Porter would become the chairman of the board of the American Water Works & Electric Company after a reorganization. He was also a director at a dozen other companies including the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Co., the Ann Arbor Railroad Co. and Chemical Bank & Trust Co. By 1900, he was on the board of directors for Brooklyn Rapid Transit. He and his companies had recovered well from Wall Street’s panic of 1893. By the time his younger brother graduated from Yale in 1905, Hobart was 40 years old and ready to help his brother seek his fortune.

Seton Porter became an accountant at his brother’s firm, Sanderson & Porter, right out of university. After only 3 months, he accepted a position in California as paymaster with the Union Construction Company, a company formed to construct the Stanislaus Electric Power Company. The company built hydroelectric dams near the summit of the Sierra Nevada Mountains that would transmit power to San Francisco. A blond-haired, blue-eyed Seton Porter continued to maintain relationships with friends in New York, hunting and sporting as a member of many highly respected clubs. It seems he was quite the tennis player! Seton’s associations with his friends from Yale would, of course, help him in the future.

After WWI, the US government formed the Emergency Fleet Corporation, led by Charles Schwab, and Sanderson & Porter was among the shipbuilding companies to win contracts to build ships for the fleet. The firm sent representatives to the Pacific Northwest to locate shipyards, and they found Raymond, with its location on the Willapa River and proximity to thousands of acres of forestland and the Pacific Ocean. Seton Porter was involved with the business of building ten cargo ships at their new Raymond shipyard site. The shipyard only produced ships for Sanderson and Porter until 1919, which is about the time we start to see Seton Porter focus his energies on the American oil industry.

Seton Porter would marry three times during his life- first to Miss Gertrude Cheever in 1911, to Marie Alexander Barrows in 1926, and finally to Fredericka V. Berwind in 1936. Seton Porter’s private life is often glazed over, but his social standing and his ability to manipulate almost any situation he found himself in cannot be ignored. His connections ultimately made the man.

Part 2

By the mid-19 teens, Seton Porter was busy diversifying his business interests…and playing quite a lot of tennis competing in club tournaments. His social calendar, however, did not stop him from representing his brother’s firm, Sanderson and Porter, whenever he was called upon to travel and survey project sites. In January 1917, Seton was doing just that- overseeing the building of factories down in Fairmont, West Virginia. By April, the country had gone to war. That May, he was sent west to Washington state to survey sites for a shipyard where Sanderson & Porter could build cargo supply ships meant to transport American goods to Europe. In other words, Sanderson and Porter were acting in the interest of the US government. The site was purchased with US treasury funds, but the ships would be built by Sanderson & Porter’s engineers. To be clear, these government contracts were not orchestrated by Seton Porter, but by his brother and the company he was working for. While he had been dealing with state government politics in his work with utilities and construction, there is little doubt that the war gave Seton Porter a great deal more experience in dealing directly with government agencies.

Meanwhile, in the whiskey industry, America’s whiskey distilleries had been ramping up production as World War I threatened to cut off their grain supplies. They had been right to stock their warehouses with newly filled barrels because on August 10, 1917, the Lever Act, otherwise known as the Food and Fuel Act (or its longer name- “An Act to provide further for the national security and defense by encouraging the production, conserving the supply, and controlling the distribution of food products and fuel”) was passed by Congress. The nation’s distillers were all forced to shut down production to conserve grain supplies for the war effort. Their recent production push was going to hold them over for the next few years, but the temperance movement was bearing down on them as well. Even distillers that had been in denial about the movement for National Prohibition were beginning to realize that the end was near when Congress approved the “Resolution to enact National Prohibition” just a few months after the Lever Act was passed.

Grain and whiskey were obviously NOT the only American product being conserved for the war effort. It’s unclear whether Seton Porter was involved in the whiskey trade at all before Prohibition, but his connection to his brother’s company, Sanderson & Porter, connected him to water works, electrical power, ship building, railroads, iron, steel, and oil. Whiskey was big business and Seton Porter was immersed in big business. Even as a young man, his work had him moving through the upper echelons of trade and politics.

By 1920, Seton Porter was acting as general manager of the Brooklyn City Railroad Company and was president of the American Oil Engineering Corporation. He had also been elected to serve as a director of the Livingston Petroleum Corporation. Porter was in the midst of American oil production growth and the fight to control the country’s oil fields. There were questions about how much more oil could be pumped out of America’s mid-continental oil field- meaning those in Kansas, Oklahoma, northern Texas and Northern Louisiana. The government had begun to seize land to protect the country’s oil reserves, so much of the finest oil fields in California were kept idle. Enter the Teapot Dome Scandal. For those that don’t remember that history class lesson, the Teapot Dome Scandal had been the biggest political scandal in American history before Watergate took its place. Oil production fields (namely the Teapot Dome field in Wyoming) that were earmarked as Naval oil reserves by President Taft had been leased without any competitive bidding. The US Interior Secretary, Albert Bacon Fall, had been found guilty of accepting gifts in exchange for leasing oil production rights at Teapot Dome to Harry Sinclair of the Sinclair Oil Corporation and that of Elk Hills in California to Edward Doheny of Pan American Petroleum and Transport Company. Fall was sent to prison for a year, but he wasn’t alone. Harry Sinclair was given three months for contempt of court after not answering any of the court’s questions. He was given an additional 6 months (though he would not serve them all) and Harry Mason Day was given 4 months jail time- both sentences were given for jury-shadowing. Who was Harry Mason Day, you ask? Day was, in the context of the Teapot Dome Scandal, Harry Sinclair’s fixer…but he was so much more than that.

Harry Mason Day was the son of an import tradesman and became one himself. He was involved with international trade throughout his career but handled a great deal of trade for the US government as well. In 1921, Day was president of the American Foreign Trade Corporation. He was appointed the Trustee for the Union of Foreign Trade and had been given the oil rights, lumber concession, licorice root and tobacco monopolies for the Caucasus (a transcontinental region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea). While he was acting as a purchasing agent in the interest of the United States government, he remained a private citizen. This was a highly politicized post because Azerbaidjan, Georgia and Armenia were Soviet government territories and Day was experimentally opening new trade relations with the area. American companies were seeking oil rights in Russia and Harry Day was right in the center of those efforts. The post WWI era was putting lots of money in Mr. Day’s pockets. Day’s association with Harry Sinclair was quite close and became quite public after the Teapot Dome Scandal. His associations with Seton Porter (among many other associates in the oil, lumber, and tobacco industries) are very vague. What is clear is that after Harry Mason Day served his jailtime for jury-shadowing in 1929, he went right back to his position at Sinclair Oil. His was also one of the first phone numbers that Seton Porter called when he was placed in a position to take over US Food Products Corporation in 1932. But I’m getting ahead of myself…More tomorrow.

Harry Mason Day was the son of an import tradesman and became one himself. He was involved with international trade throughout his career but handled a great deal of trade for the US government as well. In 1921, Day was president of the American Foreign Trade Corporation. He was appointed the Trustee for the Union of Foreign Trade and had been given the oil rights, lumber concession, licorice root and tobacco monopolies for the Caucasus (a transcontinental region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea). While he was acting as a purchasing agent in the interest of the United States government, he remained a private citizen. This was a highly politicized post because Azerbaidjan, Georgia and Armenia were Soviet government territories and Day was experimentally opening new trade relations with the area. American companies were seeking oil rights in Russia and Harry Day was right in the center of those efforts. The post WWI era was putting lots of money in Mr. Day’s pockets. Day’s association with Harry Sinclair was quite close and became quite public after the Teapot Dome Scandal. His associations with Seton Porter (among many other associates in the oil, lumber, and tobacco industries) are very vague. What is clear is that after Harry Mason Day served his jailtime for jury-shadowing in 1929, he went right back to his position at Sinclair Oil. His was also one of the first phone numbers that Seton Porter called when he was placed in a position to take over US Food Products Corporation in 1932. But I’m getting ahead of myself…More tomorrow.

Part 3

One of the reasons I felt the need to confront this research on Seton Porter was because the details around his transition to president of National Distillers has always been glossed over. It is often written that when the United States Food Products Corporation went in bankruptcy, Seton Porter was called in to assess the damage as a representative of Sanderson & Porter. He was then appointed to serve as president of the company, and…yadda, yadda, yadda…Seton Porter became the president of National Distillers, a company that would go on to become the largest liquor company in the world. It was all so grandiose and unbelievable. What was the US Food Products Company anyway? It sounds benign enough, doesn’t it? And where did this miraculous guy come from anyway? There was nothing to satisfy my need to know more. So, down the rabbit hole I went. You’ve read his impressive background, but let’s look at what happened when Seton Porter met his new friend, Prohibition.

The United States Food Products Corporation was once known as the Whiskey Trust. The original Whiskey Trust, the Distillers and Cattle Feeders Company, itself in incorporated rebranding of an earlier version of the trust, was reformed as the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (ASMC) in 1895 after the anti-trust laws forced the company to dissolve. It immediately restructured. in 1899, the reformed Whiskey Trust attempted to control the entirety of America’s whiskey production by forming the Distilling Company of America, but they failed to gain control of America’s pure rye producers, the most valuable piece of the plan. This forced the company to reimagine itself yet again as Distiller’s Securities Company in 1902. While the trust’s home offices and leadership changed over time, the company’s holdings and subsidiaries remained the same. In essence, the trust had not changed much from 1895 until Prohibition, other than its being reimagined under different corporate aliases. In 1919, Distillers Securities, under the leadership of Julius Kessler, reorganized again under a new name- the U.S. Food Products Company. The threat of Prohibition was imminent, and the company saw their future in cereals, denatured alcohol, vinegar, yeast, oil and feed products. Unfortunately, so did the rest of the country. US Food Products Co. was forced into involuntary bankruptcy in 1922. And who was called in to act as receiver-manager of the company’s subsidiaries and properties? None other than Seton Porter, as a representative of his brother’s company, Sanderson & Porter. It seems that Seton wasn’t taking Prohibition seriously in his personal life, because just over a month after being made receiver-manager of the old Whiskey Trust, he and a group of more than 50 other wealthy socialites were placed under investigation for “bootlegging activities in club and social circles.” It seems Porter was caught with a group of other men drinking at a bachelor party for R. Bartow Read in a club on Park Avenue. Nothing came of it, of course, but it’s clear that Seton Porter believed that Prohibition laws did not apply to him.

Sanderson & Porter placed Seton Porter into the role of president of the US Food Products Company in 1922. This also made him president of the Kentucky Distillers and Warehouse Company, a subsidiary of US Food Products. He reduced the company’s expenses by moving the Whiskey Trust’s remaining 70,000 barrels of aged whiskey from 20-odd Kentucky locations into the company’s Elk Run Distillery warehouses. Also that year, Congress simultaneously passed the Concentration Act, which effectively forced the consolidation of all the whiskey in the country into 24-30 government-controlled warehouse locations, 12 of which were conveniently located in Kentucky.

After Porter trimmed and tweaked the holdings of the giant corporation, he reorganized the old whiskey trust yet again. As of July 1924, US Food Products Corporation would now be known as National Distillers’ Products Corporation. He knew which direction the company should go, and it wouldn’t be food. That same year, The Fleishmann Company sued Liberty Yeast Company, a subsidiary of National Distillers, in the US District Court on 10 charges of patent infringement. Newspaper rumors swirled around the Fleishmann Company buying up National Distillers, and their stock rose over 6 1/2 points because of it. After months of stalling and renegotiating, Seton Porter sold Liberty Yeast Company to the Fleischmann Company for 4 million dollars in October 1925. Most of the sale went toward paying off outstanding debts belonging to National Distillers. (It was lucky that the stock value of the Fleischmann Company rose in the interim. I’m sure that wasn’t engineered at all…)

Seton Porter was among the experts called to advise Congress on how to proceed with decisions regarding the liquor trade throughout the 1920s. General Lincoln C. Andrews, Assistant Secretary in charge of Customs, Coast Guard, and Prohibition admitted that Seton Porter’s recommendations were often applied to legislative decisions. In 1927, The American Spirits Manufacturing Company was restructured to become the American Medicinal Spirits Company, a name more suited to its purpose. That same year, the American Medicinal Spirits Company, which already controlled the Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Co., purchased another 5 major consolidation warehouse sites: the R.E. Wathen & Co., F.S. Ashbrook Distilling Co., Hill & Hill Distilling Co., E.H. Taylor & Sons, and the Baltimore Distilling Co. Seton Porter now controlled over 50% of Kentucky’s whiskey stocks and nearly 30% of the country’s whiskey stocks. He would have the ear of the Treasury Department when the decisions were made as to who would be allowed to distill medicinal whiskey over the next few years. Porter’s influence within the Treasury Department and with the Prohibition Commission was quiet and conducted behind the scenes with the same men he mingled with in Newport, Rockport, and in New York’s clubs. When asked about the liquor trade during Prohibition, he would always side with temperance, while his National Distillers Products Corporation continued to climb in the stock market.

By the time Repeal seemed imminent, Seton Porter was ready. He called his old friend Harry Mason Day to help him corner the market in every way possible. Day, who was a leading partner at the New York stockbroking/ banking firm of Redmond & Co., and asked him to invest, which he did at $16 per share. Harry Day bought 20,000 shares in National Distillers then reached out to William E. Levis of the Owens-Illinois Glass Company. Levis bought 40,000 shares (and apparently a seat on the company’s board of directors). Day became Porter’s right-hand man, promoting National Distillers stock through his firm and finding avenues that secured its place at the top. Through Day’s efforts, National Distillers stock value rose from $16 a share to $124. The windfall would allow National Distillers to buy up as much available mature whiskey as possible. Then Seton met with some fellow Yale graduates for lunch and arranged for Charles Adams’ newly incorporated Penn-Maryland, Inc. to handle National Distillers’ blended whiskeys and for Charles S. Munson’s U.S. Industrial Alcohol (already half owned by National Distillers) to handle industrial alcohol production for the company. J.P.Morgan’s Standard Brands would come on board, as well, to make Penn-Maryland’s gin. Standard Brands brought Fleischmann’s back into the fold. In November 1933, before Repeal became a reality, Seton Porter was part of a team of experts called the “code authority” which helped to draw up drafts for Roosevelt administration’s “Codes of Fair Competition for the Distilled Spirits Industry.” The Secretary of Agriculture and the President’s Special Committee for the “Control of Alcohol and Alcoholic Beverages” drew up a plan that would impose rigid Federal control on the whole liquor business until Congress was able to tackle the subject. The code’s main provisions were:

- A Federal Alcohol Control Administration would rule the industry without benefit of any liquor representatives.

- No additions to present plant capacities except by a certificate of necessity from the FACA and absolute control of production and distribution through a quota system.

- Power to fix prices.

- An agreement with the Secretary of Agriculture to pay “parity” prices established by him for raw materials.

The new codes drove America’s whiskey men to Washington to plead their cases and explain how unfair these regulations were. It had also been their understanding that industry’s future would be decided by the states, yet here, the federal government seemed to be back in the saddle again. Perhaps the only person to completely benefit from the “code authority’s” plans was Seton Porter and his National Distillers. He now controlled most of the whiskey in the country. He pushed to limit the sale of whiskey to bottles in cases instead of the wholesale sale of whiskey in barrels as had always been the industry’s preference. He held some of the best distribution networks in the country (including the Alex D. Shaw & Co., an import firm). But enough had never been enough for Seton Porter.

In September 1933, Seton Porter sent a letter along with Joe Kennedy and a young, impressionable Jimmy Roosevelt to deliver on their trip to visit with Winston Churchill in 1933. Porter had promised all of National Distillers New England trade to Joe Kennedy, so acting as personal courier for a letter was no imposition between friends. The purpose of their trip to England was to convince Churchill to invest in National Distillers, continue to invest in Seton’s brother’s venture in the Brooklyn Manhattan Transit (BMT) line, and to woo the British into giving Kennedy to rights to import scotch, gin and other liquors into the United States (for the benefit of National Distillers, of course). The trip was successful and Churchill made a cozy 10% profit after buying and quickly selling the shares he bought.

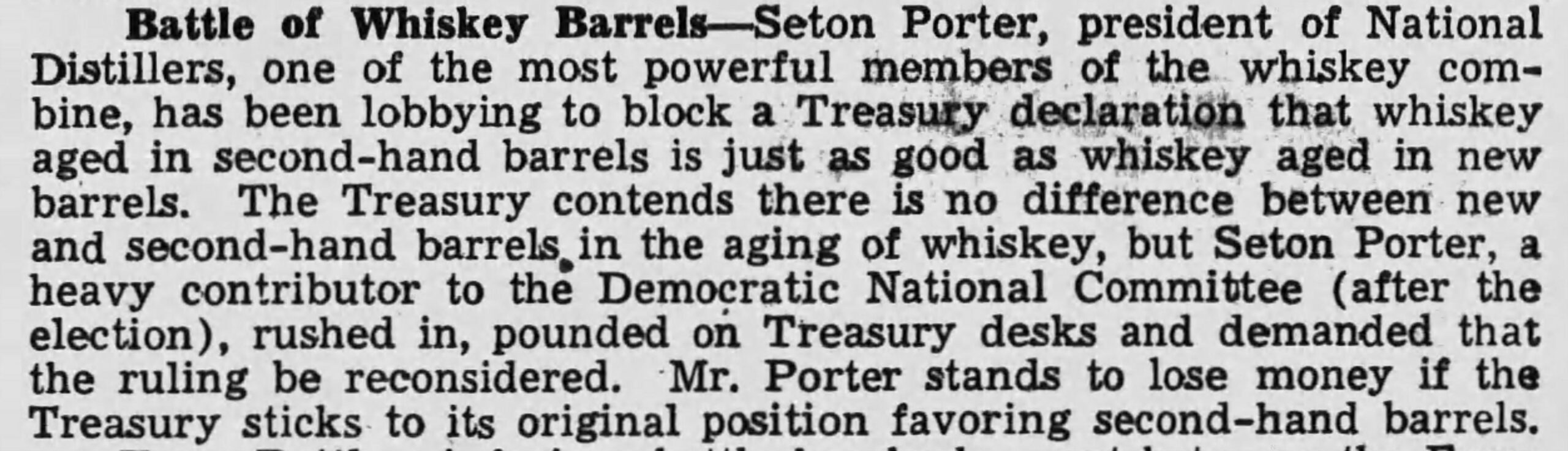

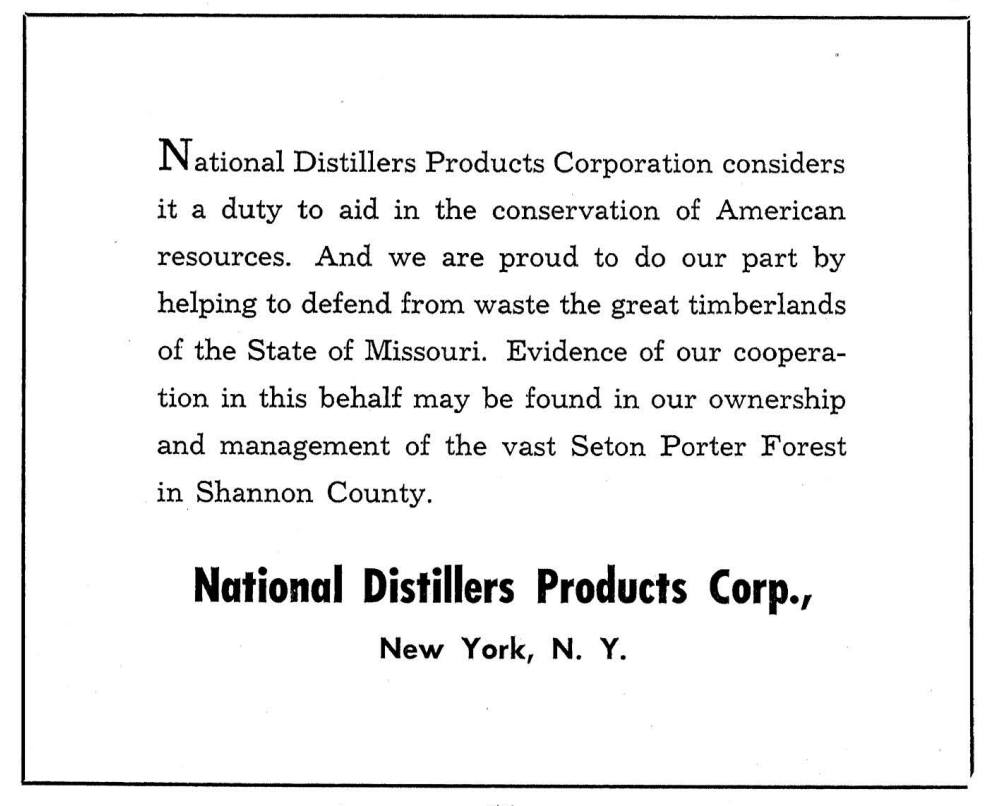

Seton Porter had yet another ace up his sleeve after FDR’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau passed a regulation requiring the use of new charred oak barrels on July 1st, 1938. He literally bought a forest on behalf of National Distillers- A 90,000 acre American white oak forest in the Ozarks to be precise. Humbly named Seton Porter Forest, it was to be one of the first sustainably managed timber forests in the country. A draw back for the rest of the industry was that if anyone wanted barrels assembled by cooperages that dealt with lumber sourced from Seton Porter Forest, they had to wait in line behind National Distillers. There are examples of Julian Van Winkle writing to Seton Porter asking for timelines on when staves would become available. Porter’s answers were slow and less than helpful.

Seton Porter had yet another ace up his sleeve after FDR’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau passed a regulation requiring the use of new charred oak barrels on July 1st, 1938. He literally bought a forest on behalf of National Distillers- A 90,000 acre American white oak forest in the Ozarks to be precise. Humbly named Seton Porter Forest, it was to be one of the first sustainably managed timber forests in the country. A draw back for the rest of the industry was that if anyone wanted barrels assembled by cooperages that dealt with lumber sourced from Seton Porter Forest, they had to wait in line behind National Distillers. There are examples of Julian Van Winkle writing to Seton Porter asking for timelines on when staves would become available. Porter’s answers were slow and less than helpful.

The rest is history, of course. It’s quite difficult to summarize a man like Seton Porter. After three parts, I think I’m exhausted. This man needs a book written about him. I hope I’ve been able to explain that Seton Porter was a great deal more than his association with National Distillers. Many lovers of American whiskey history have seen National Distillers ads from the 1930s that explain the state of the industry and promote the warehouses of pre-Pro straight whiskey at their disposal. Seton Porter likely fancied himself giving his own version of a straight-forward “fire-side chat” in print with America’s drinking public. National Distillers always wanted to be the elite whiskey company with all the finest brands. Seton Porter was able to make America nostalgic for the old days and re-take the respect that American whiskey once commanded. But the liquor industry is not, and has never been, a growth industry. It has its limits, and no corporation will settle for any less than more, so Porter would retire in 1949 as the company ventured into chemicals and other growth industries. Perhaps coincidentally, 1949 was the same year that National Distillers was under investigation by Congress for monopolistic activities. The investigation was summarily dropped and the reason for its being dropped remains unclear. Seton Porter would live for another 4 years. He died on February 7, 1953. As with most powerful men, his obituaries never mention his early years and mask most of his life in congratulatory sentiments. It’s worth knowing more about him, though. I hope I’ve scratched the surface, at least.