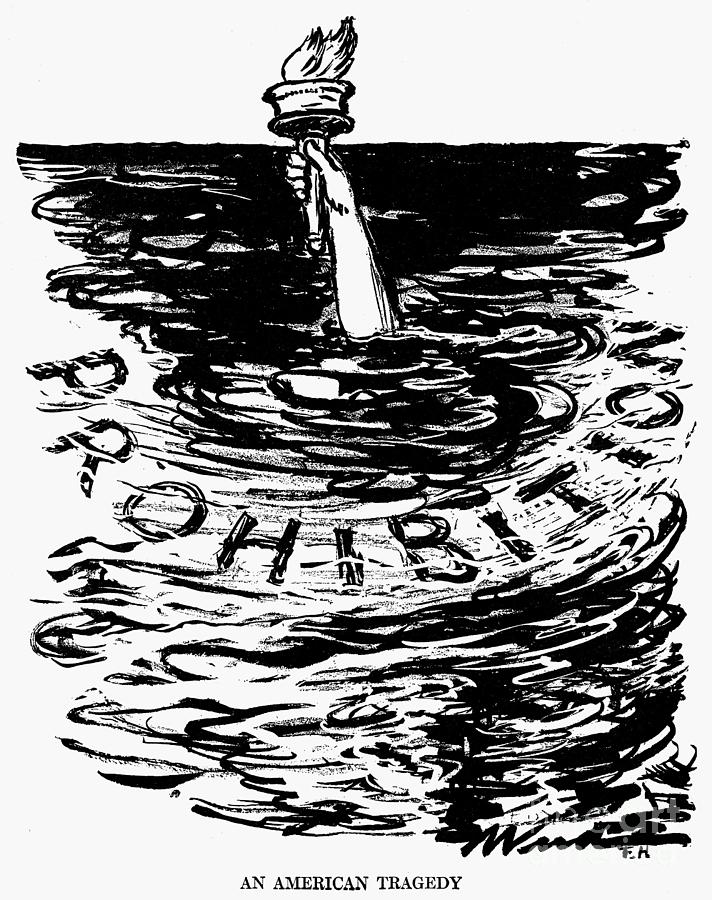

Prohibition usually conjures images of men dumping barrels or makes us think of bootleggers and gangsters with flapper girlfriends. Prohibition themed costume parties host ladies wearing fringe and sequins and men carrying plastic Tommy guns, wearing vests, and sporting spats on their shoes. But in our cartoonish modern portrayal of Prohibition, we tend to ignore the reality of the era. It’s understandable that we’d want to see Prohibition through rose tinted glasses because, in the end, America saw the error its ways and repealed the 18th amendment…right? I would argue that, sadly, we did not see the error in our ways. We were just forced to admit our failure because the country could no longer sustain such a poorly planned social experiment. Politics cannot be guided by social agendas because social agendas pit one side of the nation against another. To govern a society, we must consider it in its entirety.

Alcohol is consumed socially. It is present at gatherings held in celebration or in mourning. This social attachment to alcohol is as old as civilization- but, sadly, so is society’s need to determine who should be allowed access to it. In religion, the leader of the group handles and dispenses the alcohol. In drinking establishments, social status dictates where you choose to drink and with whom. When alcohol is given as a gift, the choice is carefully made to convey meaning upon its recipient. The type of alcohol one consumes during a meal is even connected to social status. The problem with outlawing a product so deeply rooted in our social structure is that any implementation of the law will affect citizens differently depending on where they sit in the social hierarchy.

Prohibition did not happen overnight. It began to plant seeds of influence on American society in the early 1800s. Churches sermons and religious services condemning alcohol consumption became more commonplace. Over time, people grew more willing to accept that America had a drinking problem. Working class women were particularly affected, both socially and financially. Women were limited in the type of work they could apply for and were not able to support their family on what work they could find. Their husbands, meanwhile, were working themselves to exhaustion during America’s Industrial Revolution and finding freedom/escape from their lives in their local saloon. With a household’s survival being almost entirely dependent upon the income provided by the man of the house and with very little political or social means, women turned to the only influential social organization that would listen to them- the church. Thus, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union was born. While the working class crowded the saloon after working long shifts in the factories and mines, the wealthy were leaving their offices to drink in their private clubs. All social classes drank different versions of the same ethanol, but the stigma of drunkenness was placed squarely on the poor in the saloon. While the WCTU was building social status for itself and bending the ears of politicians and judges, influential men embraced the cause (and the growing social fervor that came with it) and created the Anti-Saloon League. While the women chose to name their organization after Christian temperance which spoke to moderation and morality, the politically connected men chose to name their organization “Anti-Saloon” which was specifically targeted at saloons and casting social stigma on their customers.

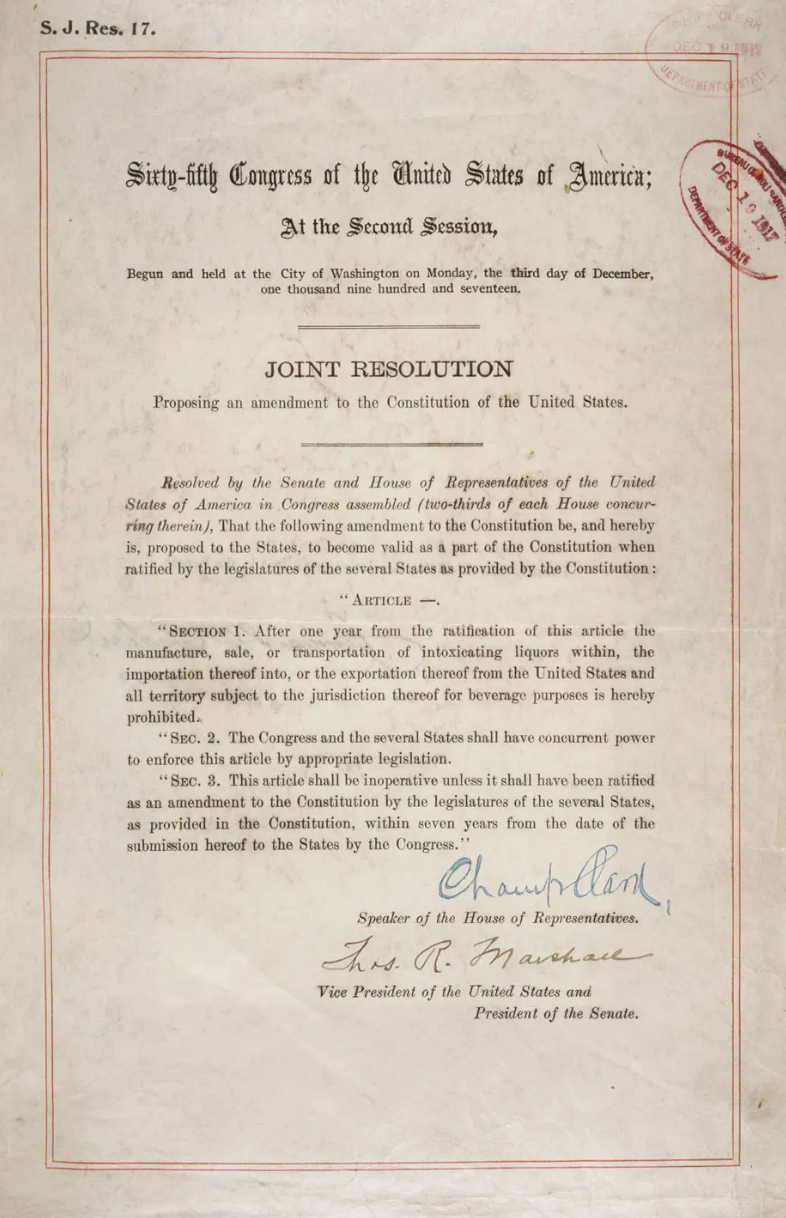

As the temperance movement gained steam, local options to create dry counties sprung up around the country. Instead of governing the businesses profiting from all this morally questionable drinking, the Anti-Saloon League and the courts sought to govern the social drinking habits of American citizens. When enough representatives in Congress had been convinced that the country needed to be controlled for its own good, a resolution to enact National Prohibition was drawn up.

It was telling how so much of the Volstead Act was designed to enforce who was and who was not given access to liquor. The three distinct purposes of the “National Prohibition Act” as described in Session I of the Sixty-Sixth Congress, Chapter S5 were:

1. “to prohibit intoxicating beverages,

2. “to regulate the manufacture, production, use, and sale of high-proof spirits for other than beverage purposes,

3. “to insure [sic] an ample supply of alcohol and promote its use in scientific research and in the development of fuel, dye, and other lawful industries.”

Most American citizens were not seeking complete prohibition from alcohol. They merely wanted the amount of liquor being consumed and distributed to be reined in. Distilleries had, after all, been flooding the markets with inexpensive liquor for the last 30 years and they showed no signs of letting up. The people wanted relief from what they saw was the moral corruption of their country. Americans were inconsistent in their thoughts on how to go about limiting access to alcohol. Many considered partial bans and asked, “Surely a little lower alcohol beer and/or wine would be allowed?” The concept of temperance over complete Prohibition was the favored position of most Americans. The Volstead Act, however, eliminated the sale of all alcohol containing “one-half of one per centum or more of alcohol by volume” which came as a shock to many citizens. While the act outlawed manufacture and transportation of alcohol without a permit, it did not specifically outlaw consumption. This basically meant that if you had alcohol, you could drink it. The wealthy owned liquor stocks and wine cellars, while the poor did not. To be fair, the Volstead Act included restrictions on the issuing of search warrants for private dwellings, but that restriction was followed by a clause stating that any items seized during a search (should one occur) shall not be returned to the owner. The burden of proof fell upon the homeowner not only to prove that the liquor seized belonged to them but also had to prove that they had no intention of selling it. The court could dispose of the seizures as they saw fit. Needless to say, many private homes were searched if there was suspicion placed upon the homeowner.

The unfortunate truth behind the Volstead Act was that it was designed to keep alcohol from working- and lower-class Americans. New laws were passed throughout Prohibition to mend the gaping holes in the Volstead Act. Each new law revealed that the government had no problem lining the pockets of the wealthy and driving a wedge between the upper and lower classes. Convictions of moonshiners making small quantities of liquor splashed the front pages of newspapers. Allegations of fraud and illegal trade of large quantities of liquor by wealthy men were also big news, but no convictions seemed to come from those indictments. The Commissioner of Prohibition, who oversaw the federal government’s enforcement of the liquor laws, worked with only a handful of wealthy, influential men to craft the laws being made during Prohibition. Each law advanced the wealth of a few so that the federal government could manage the nation’s liquor with more ease. Their desire to make “the liquor problem” go away simply allowed the funneling of responsibility into the hands of those that DID wish to manage the liquor. The companies that wished to manage all that pesky liquor grew incredibly wealthy while the Commissioner of Prohibition spent time and resources focused on ridding society of small-time bootleggers and arresting private citizens looking for a drink.

Before Prohibition, the Department of Internal Revenue created an alliance with many hundreds of distillers and filled their coffers with the millions of dollars collected from excise taxes. That alliance, even as it evolved and with all its growing pains, held for nearly 200 years. The morally driven desire to rid the country of booze did not allow room in people’s minds to consider the economic, political, and social impacts that a ban would create for the country. Instead of hundreds of distilling businesses functioning independently within a relatively healthy and competitive business environment, only a handful of businesses were allowed to remain. The years the federal government spent fighting liquor monopolies during the 1890s were cast away during Prohibition as the government determined that a monopoly able to control the output of liquor for its own purposes was actually in their interest. It was an enormous example of “throwing the baby out with the bathwater” (or the bathtub gin…). Throwing America’s liquor away was never going to work. It was too much a part of America’s social structure. There was very little rational or impartial discourse on how the distilling industry, the retail liquor industry, and the public might compromise over how to reduce public/at-work intoxication or liquor-related legal issues. When the solution to a complex social problem is complete abstinence, that solution will always be a failure.

Human nature cannot be governed by the law. The law can only govern order and accountability. Prohibition was largely an exercise in futility. Perhaps in the future, we will look at governing the institutions that create overproduction and see the flaws in allowing only the large corporations to dictate terms on how the public might best be served. Allowing the retail liquor establishments and the distiller/producers to debate the issue and find compromise would have been helpful. Finding a panel of impartial and well-informed judges to determine the best course of action would have been helpful. Allowing only the loudest moral minority to determine the fate of all American citizens was not (and will never be) a sound way to add an amendment to the Constitution, that’s for sure.

(Let’s cover some of the questionable legislation passed during Prohibition that changed American whiskey and the distilling industry forever in my next blog post.)