The Bottled in Bond Act is something that most whiskey enthusiasts can recite the basics on fairly easily. A whiskey that’s bottled-in-bond is a 100 proof, four-year-old whiskey that’s been distilled by one distillery during one distilling season, right? Well yes, but, believe it or not, that hasn’t always been the case. The Bottled in Bond Act of 1897 does not specifically state that whiskey must be four years old, though it is implied. That rule had already been established in 1894 and slightly modified in 1895. It also DID NOT SAY that whiskey must be 100 proof. It said that it can’t be LESS than 100 proof. And it certainly said nothing about the use of charred barrels. What the BIB Act of 1897 did state very clearly was that bottled in bond whiskey must be from the same distillery and made during the same distilling season. All legislation passed on March 3, 1897, of which the Bottled in Bond Act was a part, was signed by President Cleveland into law the day before he left office after completing his final term in the White House.

The BIB Act has been tweaked since it was first introduced in 1897. It is often said that it was the first consumer protection act, but that is not true. (You can easily google that Congressman Hendrick B. Wright of Pennsylvania made the first push for national legislation governing adulteration and misbranding of food and drugs in 1879- almost 20 years before the BIB Act. About 200 laws to protect consumers were put in place between 1879 and the passing of the Food and Drug Act in 1906.) The BIB Act doesn’t need to be the first to remain impressive, though. Setting guidelines for whiskey was a great idea! It didn’t mean the whiskey would be any good, but at least the consumer could know more about what they were buying. Neither “straight bourbon” OR “pure rye” counted as legal classifications for whiskey at the time, but “bottled-in-bond” now really meant something! Vatted whiskeys from multiple distilleries could not be labeled bottled in bond. This made unadulterated, barrel-aged whiskeys much more desirable, and that made it much more valuable.

The push for the bottled-in-bond act was an effort to secure the value of barrel-aged whiskeys during a phase of overproduction in the whiskey world. The late 1890s was a pivotal time for whiskey production because a series of economic developments were creating dynamic change within the industry. The financial crisis of 1893 severely affected every sector of the economy. New licensing fees were being implemented. Higher tariffs and excise tax rates were affecting the financial security of distilling companies. The Whiskey Trust had been flooding the market with cheap products and the value of whiskey- even straight whiskey- was dropping. By 1895, the Whiskey Trust was forced to break up after the passing of the Sherman Anti-Trust Law but was immediately reshaped as a corporation with many subsidiaries. With multiple companies all acting in concert under a parent company, the whiskey trust’s goal of creating a monopoly did not change course, but its methods would adapt with its new legal status. Now known as the American Spirits Manufacturing Company, the trust created the Kentucky Whiskey and Warehousing Company as well as an arm for distribution and another for acquisitions. Many of the powerful liquor firms were lobbying Washington to try to save the value of their products. The bottled in bond act was born out of all this activity. It’s passage certainly helped, too! Consumers, doctors, and pharmacists could seek out BIB products and know what they were getting. The makers of pure rye and straight bourbon were happy, too, because they could advertise the fact that their products were safe and “government approved.”

One of the rules laid out in the 1897 BIB Act that would prove its importance later was that bottled-in-bond whiskeys needed to state on the label who distilled the whiskey in the bottle. Seems easy enough, right? But during Prohibition, a couple dozen concentration warehouses contained all the country’s whiskey stocks- This meant that a handful of men owned whiskey from hundreds of distilleries, very little of which they made themselves.

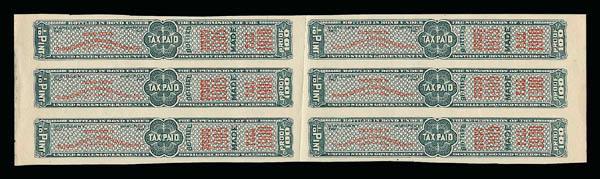

We think of medicinal whiskey during Prohibition as having been all bottled-in-bond, but that was only the case after April 1, 1923 when the US Prohibition Commissioner and Andrew Mellon, the country’s new Treasury Secretary, approved a law to force all prescriptions to meet the legal criteria for bottled-in-bond. In the early years of Prohibition, medicinal whiskey was being sold to pharmacists by distillers, wholesalers, and warehousemen, but many of these products were being diluted or blended with other products. Some barrels had already been adulterated before ever reaching a licensed pharmacist by middlemen, in transit, or by the warehouse owners themselves. (The 1922 Concentration Act had just been passed and the transportation of liquor to concentration warehouses was underway so anything was possible.) It was very unlikely that pharmacists were adding anything to purposefully harm anyone, but it was obvious that the profits from medicinal whiskey sales were moving away from concentration warehouse owners’ control. They had just invested in securing those warehouse permits and would press their advantage. Sales were quickly restricted to bottled-in-bond products only. The reason I say the decision had a lot to do with profits is because less than 4 years later*, after all the whiskey had been placed under the control of a handful of warehousemen and the bottling of all the aged whiskey stocks in their concentration warehouses began in earnest, the law was suddenly altered to allow leniency on what was considered “bottled in bond.” It is terribly convenient that the regulations devised in 1923 governed what could be sold to the public ONLY until the country’s whiskey was finally under the control a few powerful and connected companies. By 1927, the Treasury Department assumed the role of the Prohibition Commissioner’s office and instructed the warehousemen to bottle their barrel stocks to halt the aging process and gave them exclusive access to direct sales to pharmacies, effectively cutting out any middlemen. The newly bottled medicinal whiskey would still need to be labeled and stamped as bottled-in bond, so something would have to give. How would these 25 or so concentration warehouses bottle whiskeys from hundreds of defunct distilleries and be able to call that whiskey bottled in bond? It wasn’t made by their distillery during one distilling season! So Mellon allowed leniency, the bottling commenced, and the whiskey of America’s defunct distilleries began being bottled under labels belonging to a handful of companies…as bottled in bond whiskeys. Thankfully, due to that clause in the 1897 law, the original producing distillery was still made to be mentioned- if only on the back label. With exceptions being made by the Treasury Department and bottling being left to the warehousemen, it’s difficult to say just how much whiskey bottled around the time of Repeal was legitimately bottled-in-bond (as the 1897 law intended it to be). It’s also difficult to determine what whiskeys were vatted together or which may have been altered in any way. Anyone that has tasted Prohibition era whiskeys knows that a brand name can be vastly different from year to year.

The BIB Act was altered again in 1937 when the Amending Stamp Provisions Act of Bottling in Bond was passed. It stated,

“To be eligible for bottling in bond, spirits must be of domestic production, straight**; that is to say, unmixed or unblended, of precisely 100 proof, and at least 4 years old. Since the repeal of the prohibition amendment in December 1933 there have been only limited quantities of liquor which have met these requirements, and these have been used chiefly in the manufacture of blends. But little has been bottled in bond. Virtually all distilleries, however, have been accumulating stocks since the beginning or resumption of their operations at the time of repeal, and about December 1937 or January 1938 will be in a position to begin bottling spirits in bond on a large scale. As time goes on, it is expected that bottling in bond will become the rule rather than the exception, and that ultimately 50,000,000 gallons of spirits will be bottled annually under the provisions of law here referred to.”

*1927 was an important year because the Secretary of the Treasury approved the direct sale of medicinal whiskey only taking place between concentration warehousemen and pharmacies. This effectively removed any middlemen from the transaction. The immediate bottling of aging whiskey stocks was begun to halt the barrel aging process and preserve the value of the whiskey. This year also marked the start of negotiations on which distilleries would carry out the replenishing of America’s diminishing medicinal whiskey stocks. Very few men were consulted by the office of the Secretary of the Treasury. Mellon knew very well who he would appoint the permits to.

**The term straight was finally legally defined on August 29, 1935 (and effective March 1936) when the brand new Federal Alcohol Administration (early version of the TTB that never had to exist before Prohibition) approved the Federal Alcohol Administrations Act. Liquor classifications were finally set in stone.

“Straight whiskey,” as of 1936, was finally defined as “an alcoholic distillate from a fermented mash of grain distilled at not exceeding 160 proof and withdrawn from the cistern room of the distillery at not more than 110 proof and not less than 80 proof, whether or not such proof is further reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80 proof, and is-

-

Aged for not less than 12 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1936, and before July 1, 1937; or

-

Aged for not less than 18 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1937, and before July 1, 1938; or

-

Aged for not less than 24 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1938.