The following blog contains a study of the Stitzel distilleries and the men behind them.

Each of the 9 separate parts copied below were written in May and June of 2025, so this blog post below lists each part as it was published on social media. Here on DramDevotees.com, I can piece together the string of thoughts in one place. The series began with my asking the following question: “Why was A. Ph. Stitzel’s Distillery Chosen?” I was curious to know how the Stitzel Distillery’s warehouse was licensed to act as a concentration warehouse and/or to sell medicinal whiskey during Prohibition. Who were the Stitzels, and just what kinds of connections did they have within the industry anyway?

The Stitzel Distilleries- Part 1.

The Prohibition Anomaly.

Why Was A. Ph. Stitzel’s Distillery Chosen?

Medicinal whiskey production during Prohibition was limited to a handful of distillers. (I’m excluding brandy and industrial alcohol production here, though they should not be excluded when describing medicinal spirits production during Prohibition.) The distilleries that were allowed to manufacture medicinal whiskey after 1929 were owned by men with connections- meaning they all had political connections in Washington. Over the next few days, I’d like to focus on one distilling company that didn’t seem to have those connections.

There were initially about 26 to 30 distillery locations across the United States that were given permission to consolidate and store America’s whiskey stocks under US government supervision in 1922. While the running presumption in Washington D.C. was that concentration warehouse permits were to be given to those warehouse owners in places with the greatest need for medicinal whiskey stocks (high population density, societal need, hospital locations, etc.), Kentucky was given the lion’s share of permits. Licenses ended up going to men of means with connections in Washington, even if the intent was to seek central U.S. locations with convenient distribution capabilities. And before anyone says, “But Kentucky had the most whiskey,” that’s not entirely accurate. Great quantities of whiskey were being stored in the Midwest and across the country. It was the great consolidation of whiskey taking place in the early 1920s that swelled the amount of whiskey stocks being stored in Kentucky, tipping the scales toward Kentucky. (Notice Cincinnati is NOT on the list below!) The licenses/permits allowing existing warehouses to act as concentration warehouses (1922 Concentration Act) went to the following locations:

In California:

1. South End Warehouse Co., general bonded warehouse No.2, San Francisco, Ca.

2. Fresno Warehouse Co., special bonded warehouse No.7, Fresno, Ca.

3. Cook-McFarland Co., general bonded warehouse No.3, Los Angeles, Ca.

In Illinois:

1. Sibley Warehouse & Storage Co., general bonded warehouse No.5, Chicago, Ill.

2. Railway Terminal & Warehouse Co., general bonded warehouse No.6, Chicago, Ill.

3. Corning Distilling Co., distillery bonded warehouse No.22, Peoria, Ill.

In Maryland:

1. Baltimore Distilling Co., distillery bonded warehouse No.27, Baltimore, Md.

In Massachusetts:

1. Quincy Market Cold Storage & Warehouse Co., general bonded warehouse No.2, Boston, Ma.

In Missouri:

1. R.U. Leonori Auction & Storage Co., general bonded warehouse No.2, St Louis, Mo.

2. Security Warehouse & Investment Co., general bonded warehouse No.3, St. Louis, Mo.

In New York:

1. Keap Warehouses, Inc., general bonded warehouse No.2, Brooklyn, NY

2. Cosmopolitan Warehouses, Inc., general bonded warehouse No.1, New York, NY

3. F.C. Linde Co., special bonded warehouse No.2, New York, NY

In Pennsylvania:

1. Dougherty Distillery Warehouse Co., distillery bonded warehouse No.2, Philadelphia, Pa.

2. A. Overholt & Co., distillery bonded warehouse No.3, Broadford, Pa.

3. Joseph S. Finch Co., distillery bonded warehouse No.4, Pittsburgh, Pa. (concentration warehouse permit originally located in Pittsburgh until 1924 when the permit was moved to Schenley, Pa)

4. The Large Distilling Co., distillery bonded warehouse No.5, West Elizabeth, Pa. (not a true concentration warehouse, but contained whiskey that was distilled on-site in 1920 and 1921)

In Kentucky:

1. Louisville Public Warehouse Co., general bonded warehouse No.1, Louisville, Ky.

2. Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Co. (Elk Run), distillery bonded warehouse No.368, Louisville, Ky.

3. Sunny Brook Distillery Co., distillery bonded warehouse No.5, Louisville, Ky.

4. G. Lee Redmon Company, distillery bonded warehouse No.414, Louisville, Ky.

5. R.E. Wathen & Co., distillery bonded warehouse No.19, Louisville, Ky.

6. E.H. Taylor, Jr. & Sons, distillery bonded warehouse No.53, Frankfort, Ky.

7. George T. Stagg Company, distillery bonded warehouse No.113, Frankfort, Ky.

Barton Co.), distillery bonded warehouse No.24, Owensboro, Ky.

9. Hill & Hill Distilling Co., distillery bonded warehouse No.18, Owensboro, Ky.

10. F.S.Ashbrook Distillery Company, Inc., distillery bonded warehouse no.35, Cynthiana, Ky.

11. Frankfort Distillery, Inc., distillery bonded warehouse No.33, Frankfort, Ky. (The contents of this warehouse were removed to a location in Louisville, KY)

12. Joseph Wolf (James E. Pepper Distillery), distillery bonded warehouse No.5, Lexington, Ky.

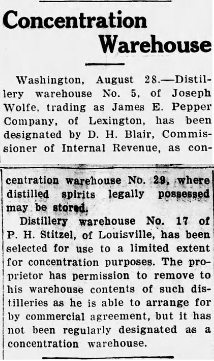

One distillery company is conspicuously absent from this list- The A. Ph. Stitzel Distillery.

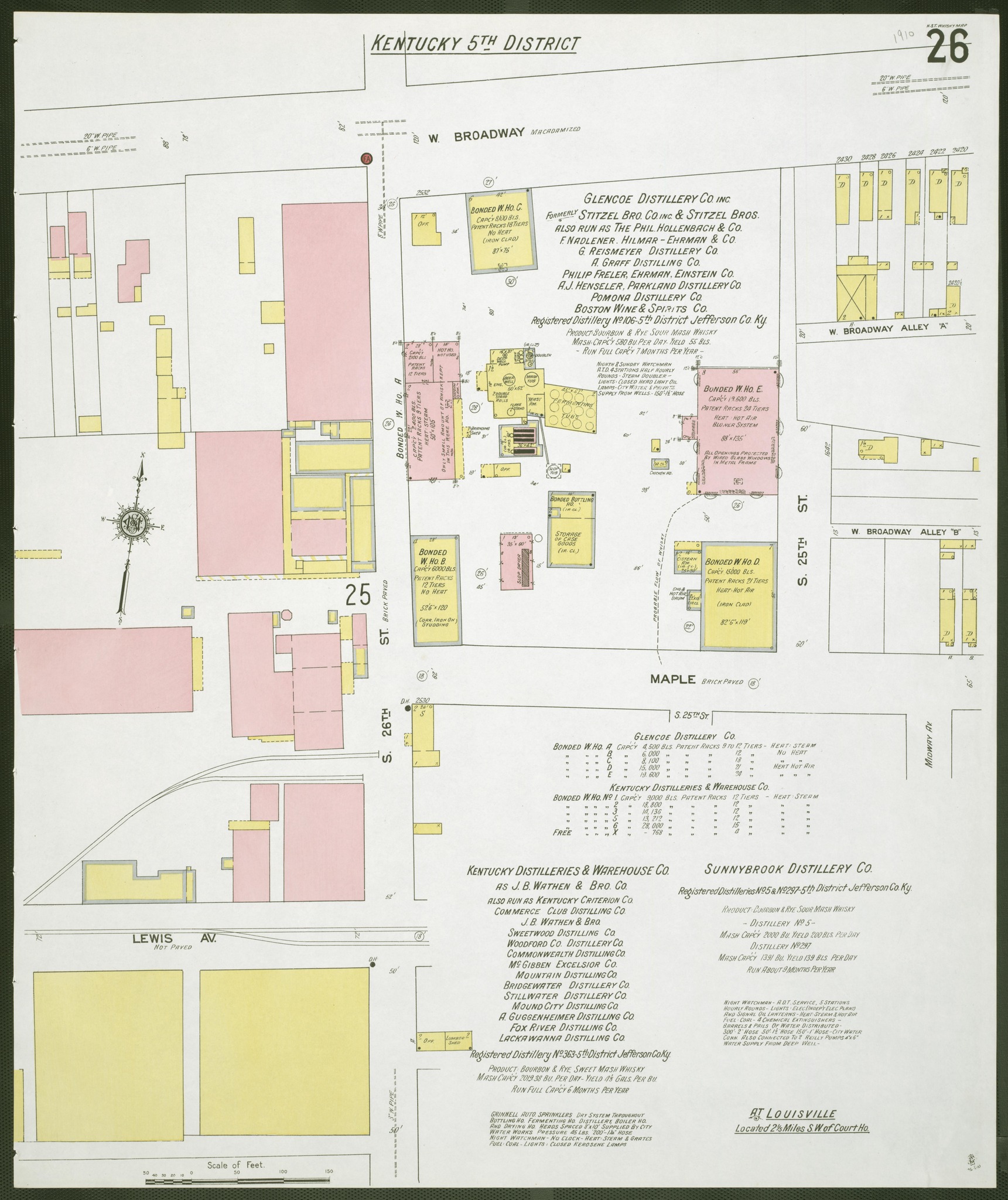

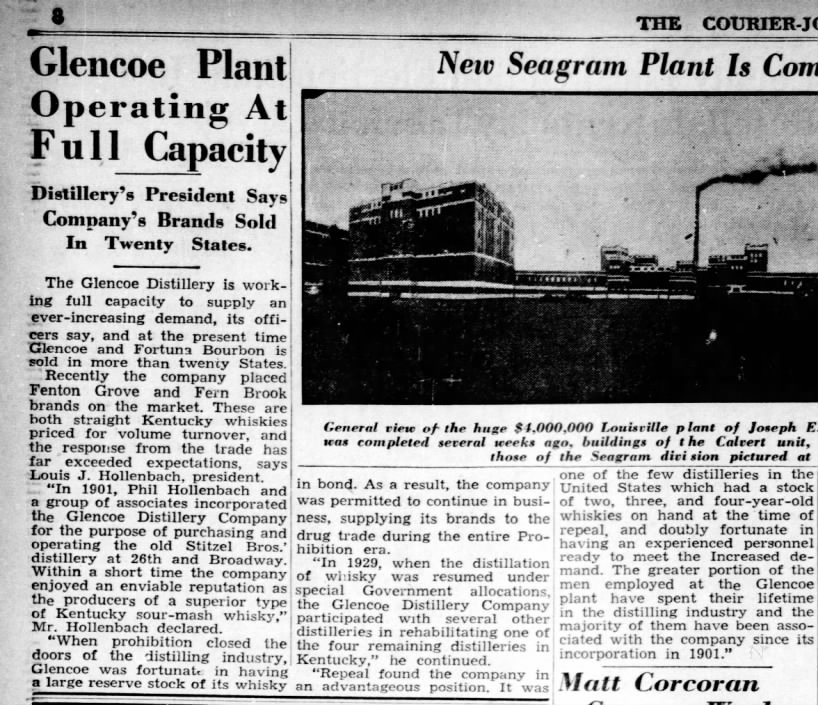

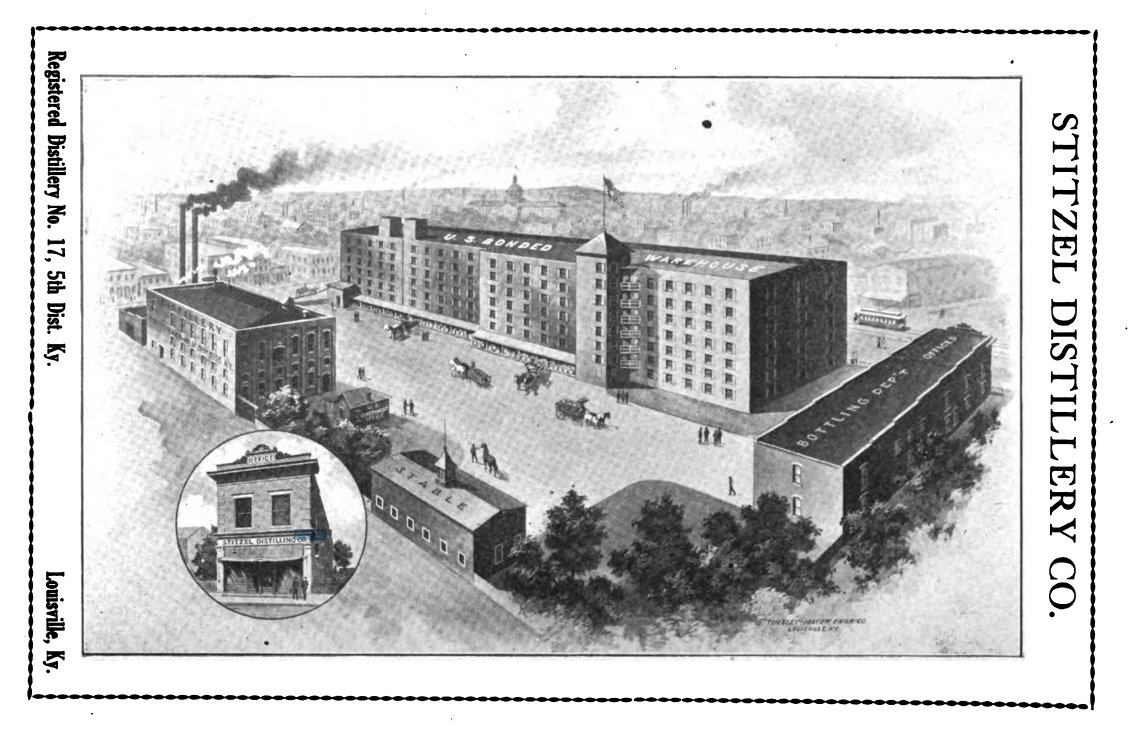

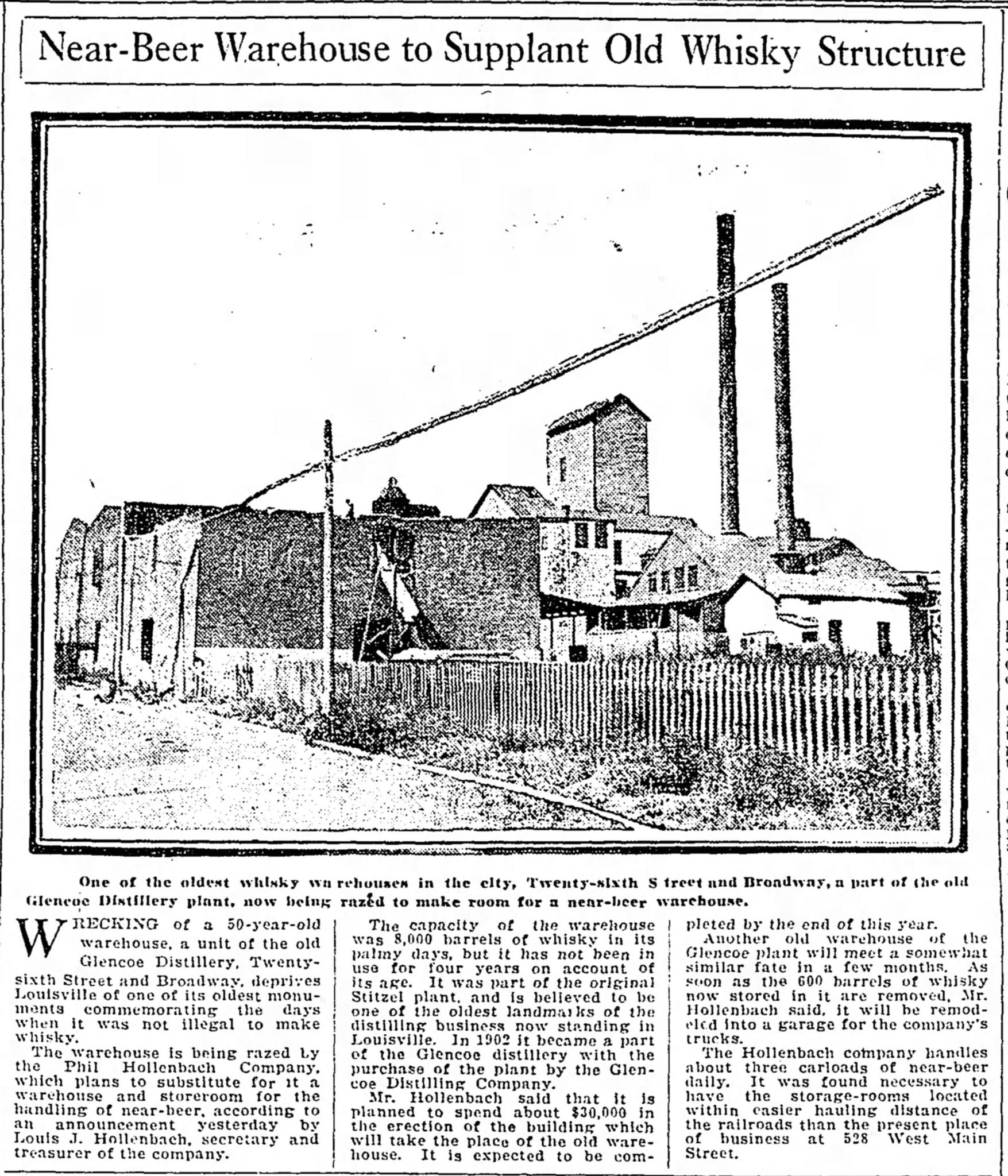

Most collectors of Prohibition-era whiskeys know that A. Ph. Stitzel’s RD #17 location bottled medicinal whiskeys. Registered Distillery #17 was on Story Avenue in Louisville, Ky. It was the third distillery built by the Stitzel family. This was NOT the location where distilling took place during Prohibition, but was given a permit to act as a concentration warehouse where medicinal whiskey could be bottled- after 1924. It was supposed to be a temporary measure, but the warehouse only grew in capacity over time. In fact, a huge new warehouse was built DURING Prohibition! The location where medicinal whiskey was manufactured for the Stitzel company, by the way, was at 26th and Broadway in Louisville, also known as the Glencoe Distillery or the Ph. Hollenbach Distillery (RD #106).

Most collectors of Prohibition-era whiskeys know that A. Ph. Stitzel’s RD #17 location bottled medicinal whiskeys. Registered Distillery #17 was on Story Avenue in Louisville, Ky. It was the third distillery built by the Stitzel family. This was NOT the location where distilling took place during Prohibition, but was given a permit to act as a concentration warehouse where medicinal whiskey could be bottled- after 1924. It was supposed to be a temporary measure, but the warehouse only grew in capacity over time. In fact, a huge new warehouse was built DURING Prohibition! The location where medicinal whiskey was manufactured for the Stitzel company, by the way, was at 26th and Broadway in Louisville, also known as the Glencoe Distillery or the Ph. Hollenbach Distillery (RD #106).

There were four Stitzel family distilleries in total, though it is unclear if those locations were unique. It is possible that the 1st and 2nd sites overlapped, but it’s unlikely- each location appears to have a unique address. (I covered a similar example of a company having multiple locations recently in my posts on Lawrenceburg, Indiana’s distilleries.) The market’s activity during the late 1800s turned distilleries into commodities. Distilleries, even while their management teams may have remained consistent, were sold and traded like hot potatoes. The names of distilleries were altered so many times that tracing which distilling company owned which distilling property at any time can be quite difficult. Corporations began to branch into subsidiaries and those branches were easily lost among the tree’s “branches”. Is it any wonder that the thought of a Stitzel Distillery having four different addresses is hard to believe? If they all had the same name, why should they be different? Therein, lies the trouble. Subsidiaries and corporate reorganizations created grey areas and confusion in the marketplace, sometimes purposefully. They have also created confusion in the research conducted around their histories. I’d like to focus on Stitzel’s history specifically because Stitzel’s distilleries are particularly confusing. I’d like to know more, so I’m going to continue to look at the company’s origins. Bear in mind, this is not an effort to smear a distillery whose history I love to love (Is my whiskey geek showing?)- It’s an effort to understand how this dark horse succeeded where SO many others failed.

There were four Stitzel family distilleries in total, though it is unclear if those locations were unique. It is possible that the 1st and 2nd sites overlapped, but it’s unlikely- each location appears to have a unique address. (I covered a similar example of a company having multiple locations recently in my posts on Lawrenceburg, Indiana’s distilleries.) The market’s activity during the late 1800s turned distilleries into commodities. Distilleries, even while their management teams may have remained consistent, were sold and traded like hot potatoes. The names of distilleries were altered so many times that tracing which distilling company owned which distilling property at any time can be quite difficult. Corporations began to branch into subsidiaries and those branches were easily lost among the tree’s “branches”. Is it any wonder that the thought of a Stitzel Distillery having four different addresses is hard to believe? If they all had the same name, why should they be different? Therein, lies the trouble. Subsidiaries and corporate reorganizations created grey areas and confusion in the marketplace, sometimes purposefully. They have also created confusion in the research conducted around their histories. I’d like to focus on Stitzel’s history specifically because Stitzel’s distilleries are particularly confusing. I’d like to know more, so I’m going to continue to look at the company’s origins. Bear in mind, this is not an effort to smear a distillery whose history I love to love (Is my whiskey geek showing?)- It’s an effort to understand how this dark horse succeeded where SO many others failed.

The Stitzel Distilleries- Part 2.

The Stitzel Men and Their Distilleries.

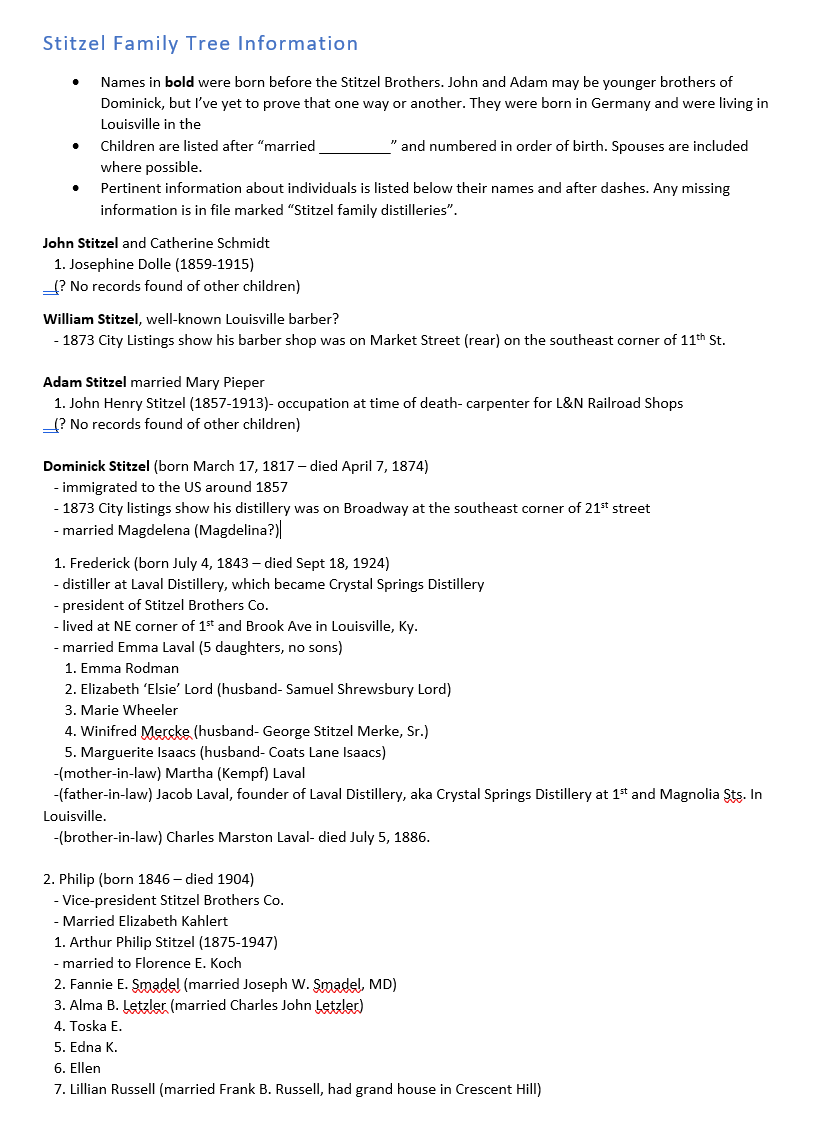

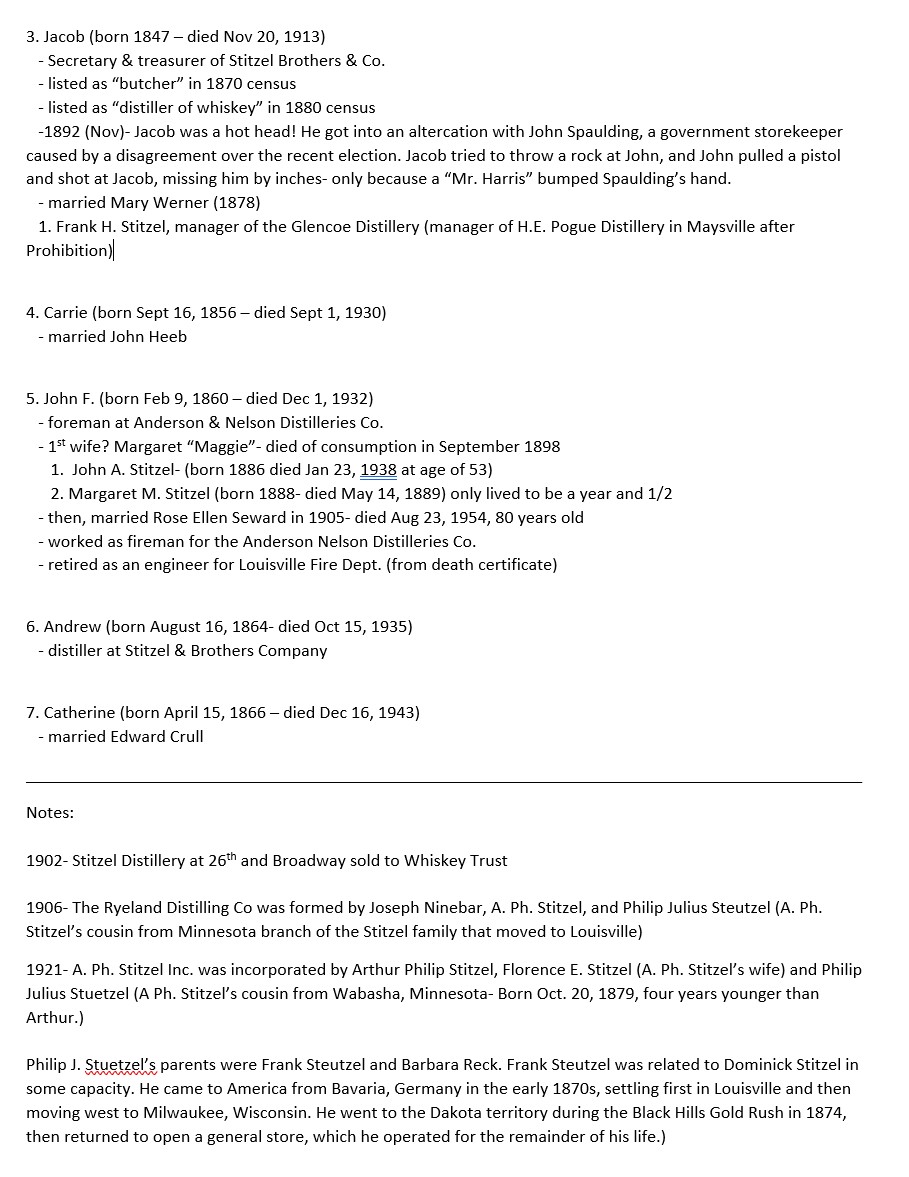

It’s unclear who was behind the original Stitzel distillery. The family’s first distillery, known as Stitzel & Bro., was built in 1872 in Louisville, Kentucky.* It appears to have been built and operated by Dominick Stitzel, the patriarch of the Stitzel family of distillers in the United States. (While little information exists about Dominick’s family, Louisville’s 1873 City directory lists a “Catharine (Schmidt) Stitzel, widow of John Stitzel” and “Mary (Paiper) Stitzel, widow to Adam J. Stitzel”. There was also a well-known barber named William Stitzel living in Louisville at the time who was son to John Stitzel. It is possible that Dominick was related to these men, though it’s unclear exactly how.) Dominick and his wife, Magdelena Zoller, both originally from Germany, were married in Louisville, Kentucky in 1859. They had 7 children together; Frederick (born 1843), Philip (born 1846), Jacob (born 1847), Carrie (married Heeb, born 1856), John (born 1860), Andrew (born 1865), and Catherine (married Crull, born 1866). Most histories describe Frederick, Jacob, and Philip Stitzel as having started their own distillery after their father’s death in 1874, but it was more nuanced than that. (Part 7 of this series covers the family tree!) Frederick Stitzel would’ve been 31 and Philip would’ve been 28 when their father died, so they likely helped to build the first Stitzel Distillery, but they certainly improved upon it while making it their own after his death.

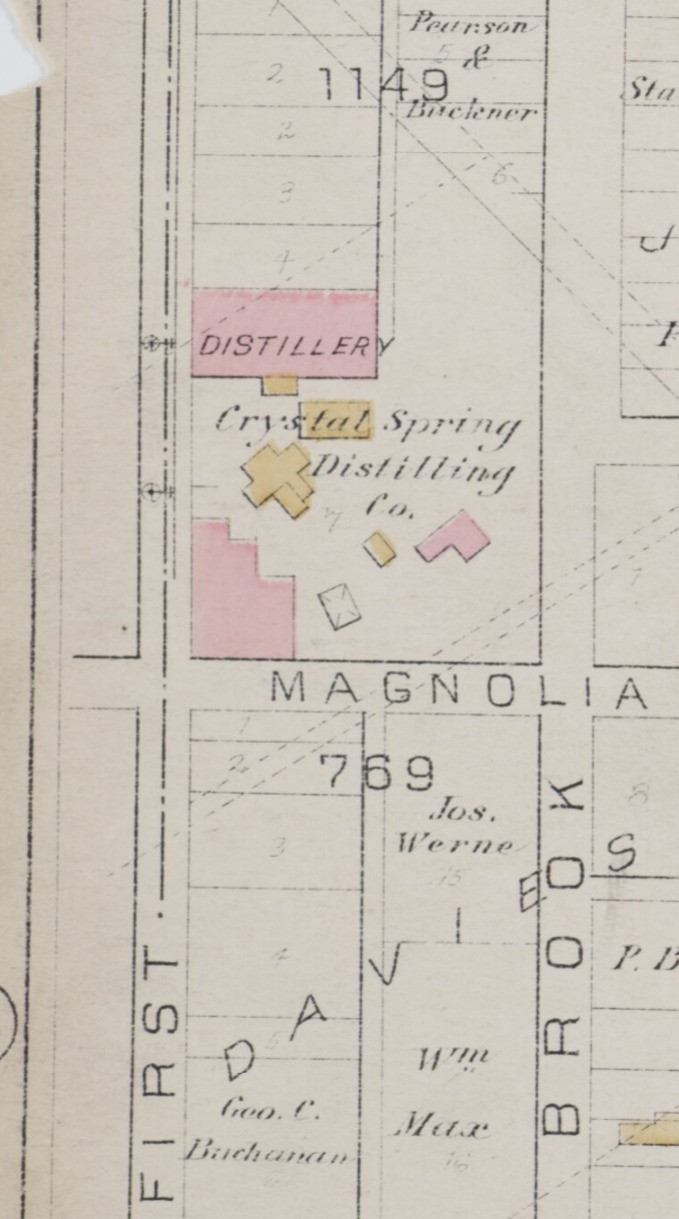

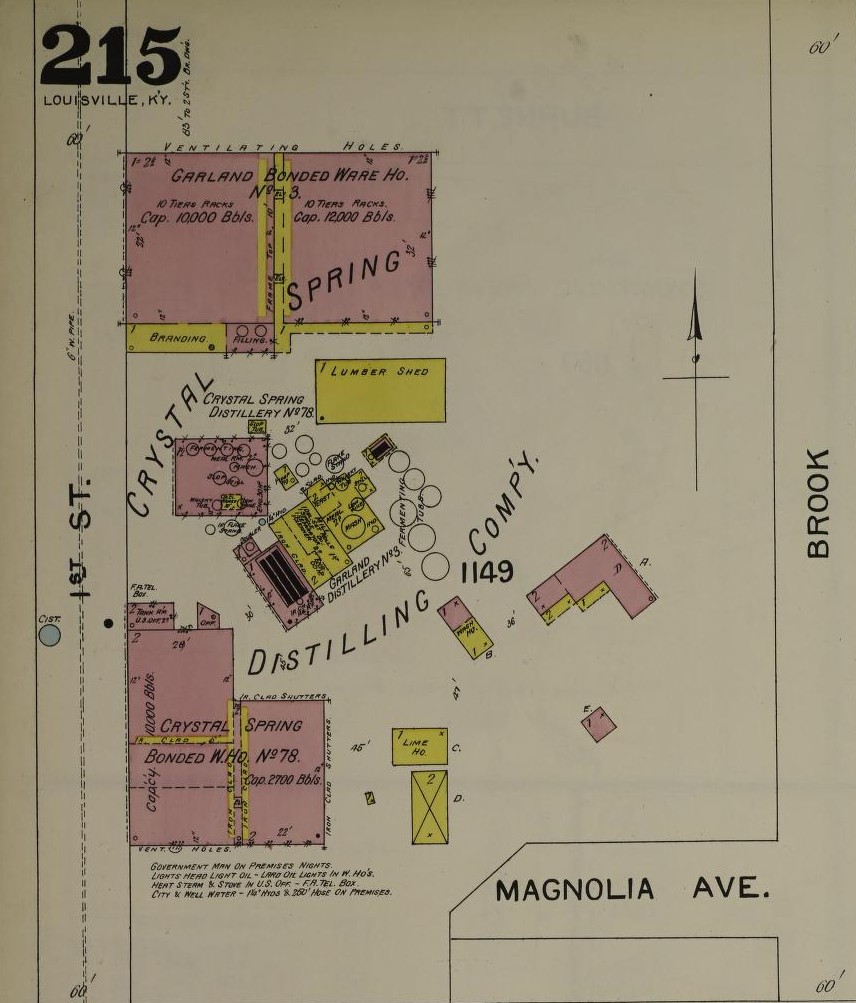

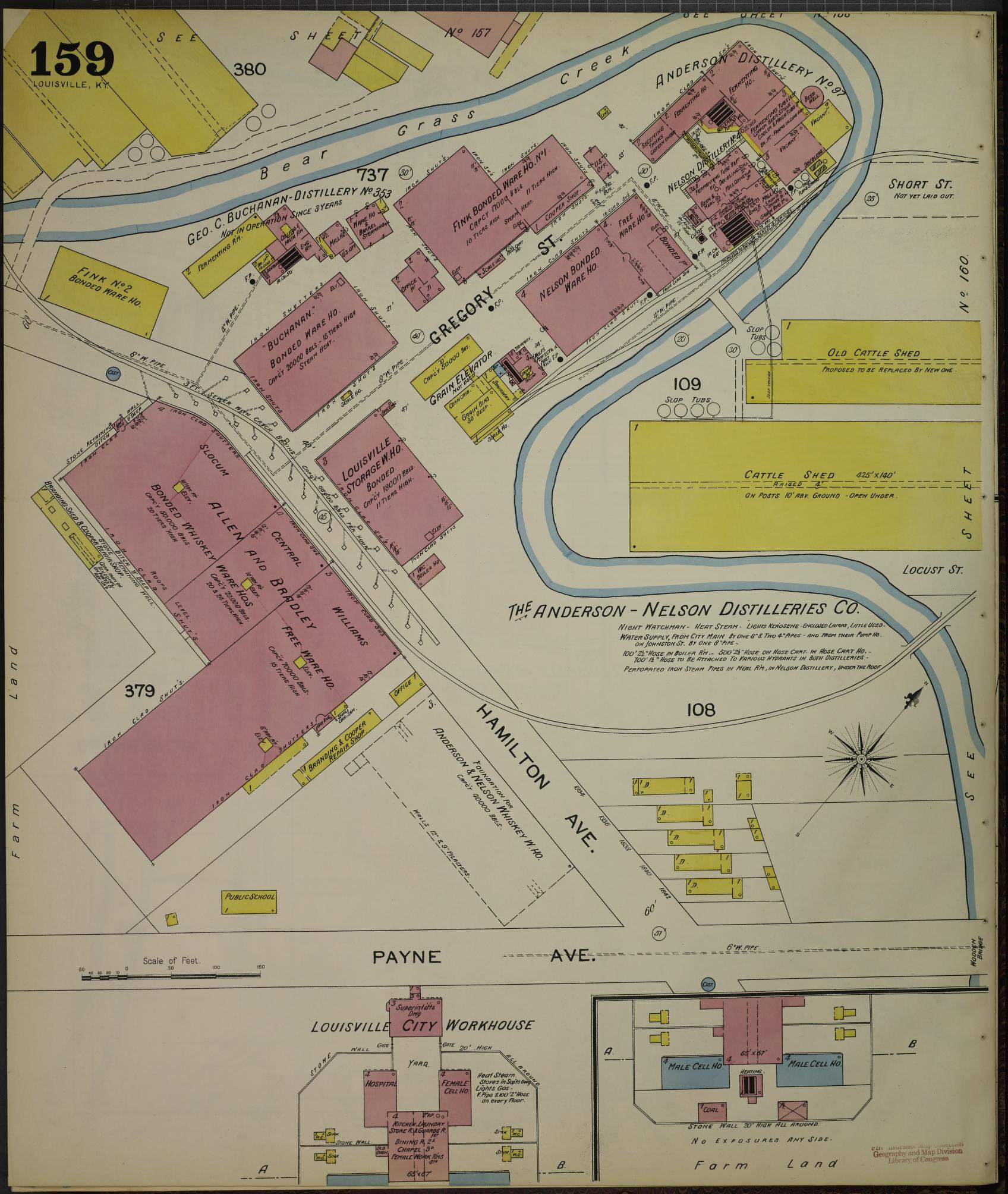

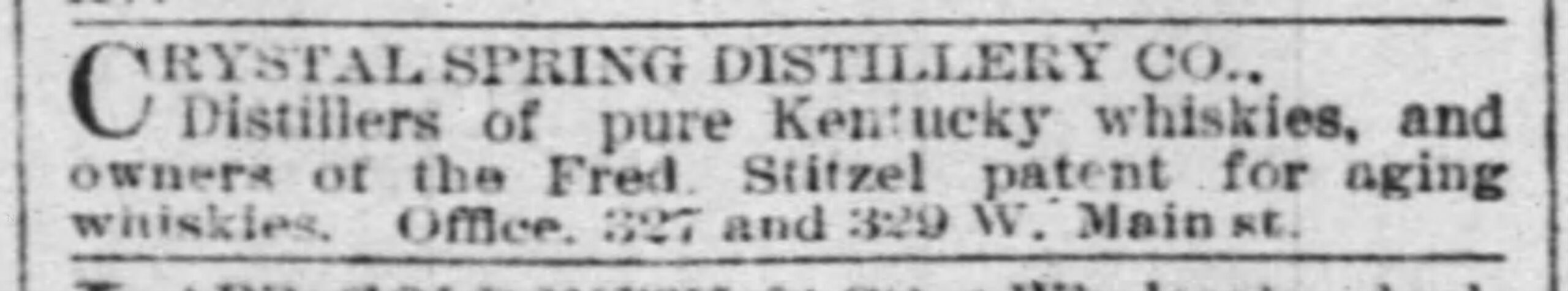

While the earliest of the Stitzel distilleries were being built, Frederick Stitzel, the eldest of Dominick’s sons, was working as a distiller for the Charles M. Laval Distillery, aka the Crystal Springs Distillery. The old Crystal Springs Distillery was located at 1st and Magnolia Streets in old Louisville. (See maps below- Today, that’s a residential neighborhood.) Jacob Laval, founder of the Laval Distillery, passed away in 1872, leaving the company to his son, Charles M. Laval. By 1874, Frederick was married to Emma Laval, sister to Charles. The Laval/Crystal Springs Distillery had been absorbed by one of the largest dealers of whiskey in the country at the time- the Newcomb-Buchanan Company. H. Victor Newcomb retired in 1871 to become director of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, leaving the Buchanan brothers to head the company. George C. and Andrew Buchanan got busy building an empire in distilleries, whiskey, cattle, and real estate in Louisville during the 1870s. Frederick Stitzel essentially became an employee of the Buchanans, even as he worked with his brother-in-law, Charles Laval, at Crystal Springs.

Louisville had been host to the Industrial Exposition from 1872 to 1873, so the future looked very bright for the Buchanans. Unfortunately, a financial panic in 1873 and stiff competition from Cincinnati and St. Louis put stress on even the largest liquor companies. Newcomb-Buchanan Co. was incorporated in 1875 and widely advertised over the next several years, but they overextended themselves. The company failed in 1878 and went into receivership.

By 1880, all Newcomb-Buchanan’s unpaid taxes were settled up with the government, and the company went back into business- with their powerful reputation within the trade still intact. Over the next several years, however, they were back in hot water with private debts, and by 1884, Newcomb-Buchanan was being accused of falsifying and duplicating receipts. Again, the company went into receivership. Their assets were auctioned off, and most of the company, with the exception of Monk’s Distillery, were sold to J.H. Lindenburger, president of a banking firm based in New York that had been buying up KY distilleries at the time. (NY’s Merchants National Bank was buying many large industrial firms for an English syndicate.) The company re-organized and incorporated in 1885 under a new name- the Anderson & Nelson Distilleries Company.

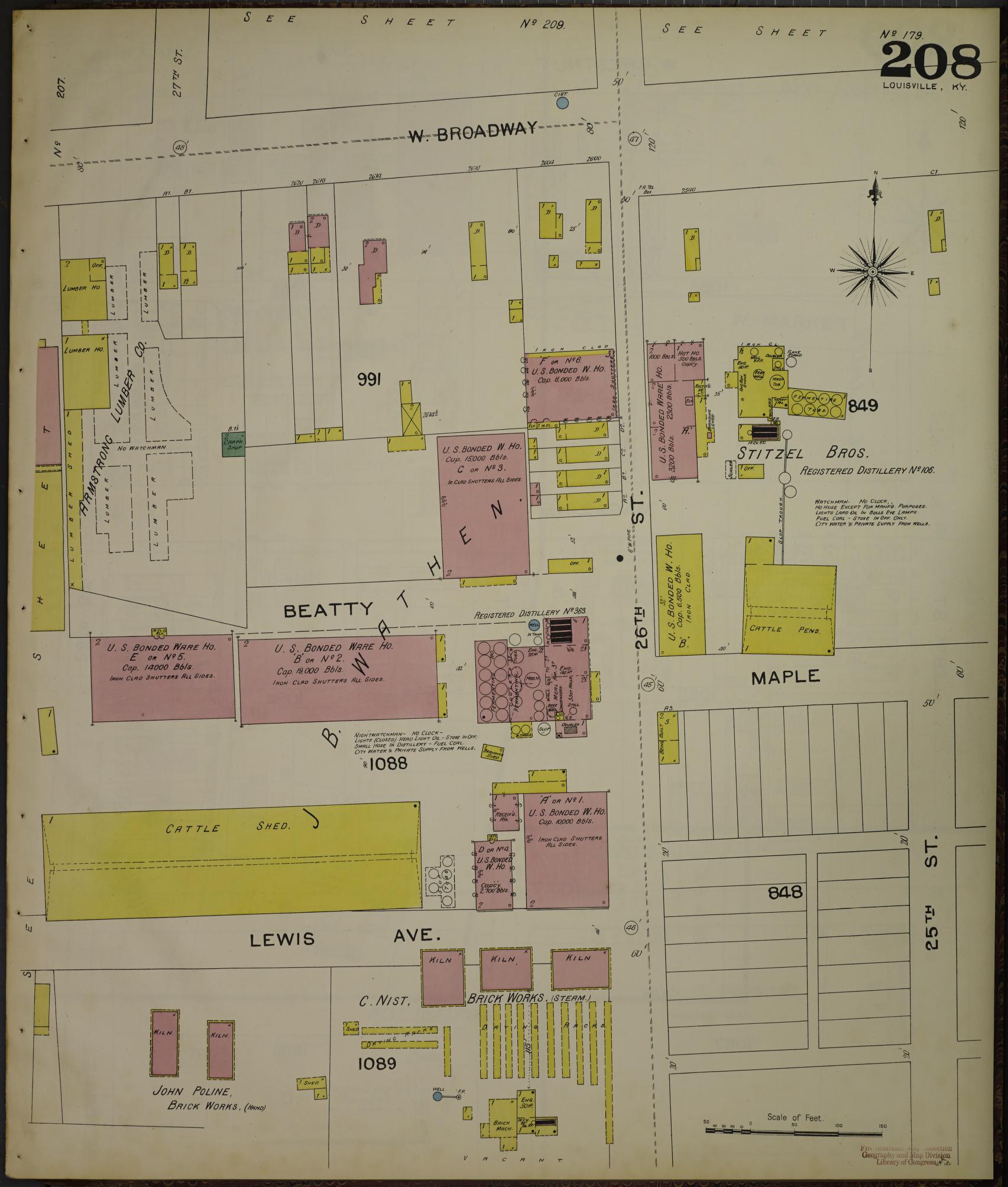

In the early 1880s, Dominick Stitzel’s eldest sons built a new distillery clear across town from their plant at 26th and Broadway. The new plant was located about 5 miles away at Buchanan and Story Avenue in Butchertown. Frederick Stitzel became president of the new Stitzel Bro. Distillery Company, Philip served as vice president, and Jacob became secretary and treasurer. It appears that both distilleries were managed by the Stitzel brothers, but ownership of original location had changed.

Several things likely led to the erection of a new plant.

1. While the second location represented an expansion of the company, it would also belong to them- something they had more control over.

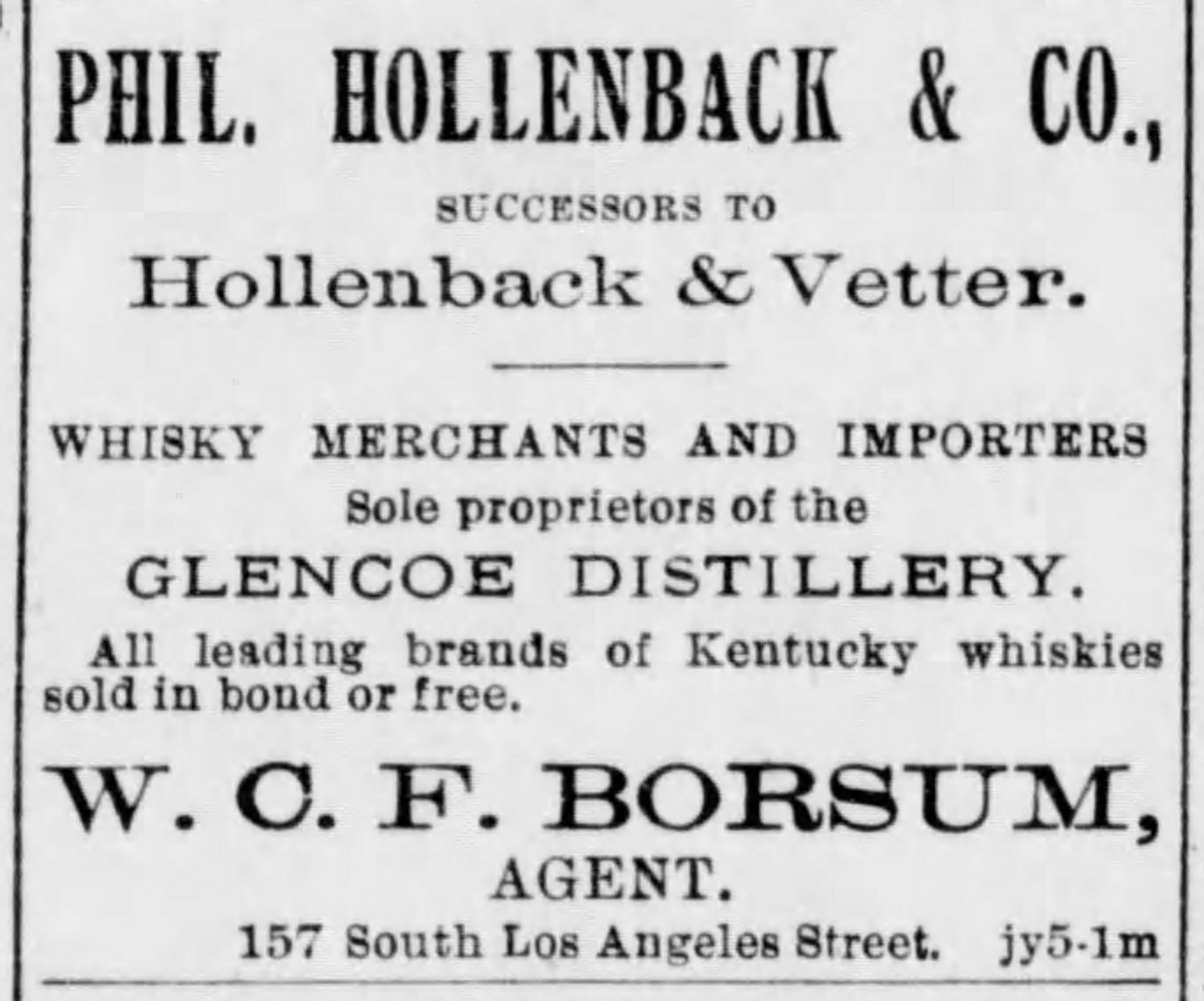

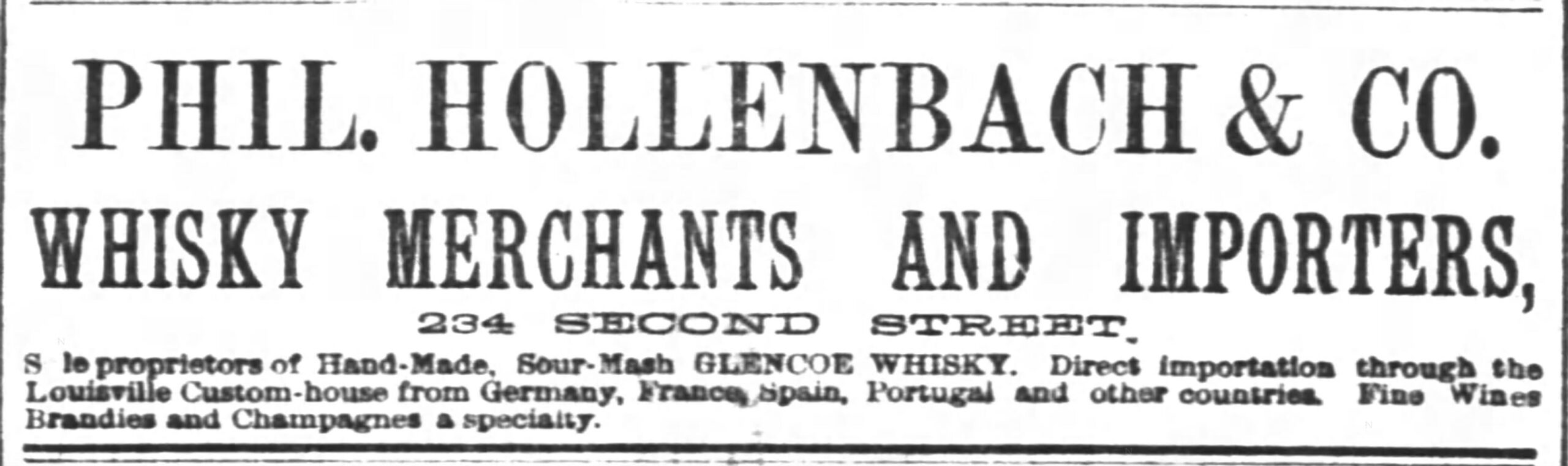

2. The financial difficulties of the Newcomb-Buchanan Company inspired new investments from different competitive firms. One of the Stitzel Bros’ biggest buyers in Louisville, Phillip Hollenbach, became proprietor of the Stitzel plant at 26th and Broadway. Hollenbach, who had been sourcing the whiskey for his “Hand Made Sour Mash Glencoe Whiskey” from the Stitzel plant, renamed the plant “Glencoe Distillery” after his famous brand. (Hollenbach also bottled Fortuna brand whiskey)

3. Frederick Stitzel remained a part of the Anderson & Nelson Distilleries Co. through his partnership with the Laval family and, later, with Fred W. Adams. The new Stitzel plant was built just across the Beargrass Creek from that grouping of distilleries (Nelson, Anderson, Buchanan distilleries & warehouses- and the Fink, Allen and Bradley warehouses). The decision to build at Story and Buchanan streets may have been due to its convenient location near the other plants Frederick was invested in.

The early 1880s also brought the youngest Stitzel brothers, John and Andrew, into the distilling business. John F. Stitzel followed in Frederick’s footsteps, working as forman for the Anderson & Nelson Distilleries Company. Andrew became distiller for the Stitzel Bros. company.

*To provide some context, the Stitzel Distillery at 26th and Broadway was built DIRECTLY across the street from the Wathen Distillery. The Wathen Distillery was on the same block as the Old Times Distillery. The Stitzel Distillery was literally next door to one of the major sites operated by the Whiskey Trust.

The Stitzel Distilleries- Part 3.

Frederick Stitzel.

Frederick Stitzel wasn’t just a distiller. He was a brilliant man. Frederick was an inventor, an investor, and a savvy businessman. His accomplishments would help to cement his family name in the history books- and not just the whiskey history books! But there were tragedies along the way- 2 of which nearly claimed his life. While we tend to assume that Frederick Stitzel’s most important achievements were related to his association with the Stitzel Brothers Distillery, I would argue that his connection to other companies had as much, if not MORE, to do with his family legacy standing the test of time.

Frederick Stitzel wasn’t just a distiller. He was a brilliant man. Frederick was an inventor, an investor, and a savvy businessman. His accomplishments would help to cement his family name in the history books- and not just the whiskey history books! But there were tragedies along the way- 2 of which nearly claimed his life. While we tend to assume that Frederick Stitzel’s most important achievements were related to his association with the Stitzel Brothers Distillery, I would argue that his connection to other companies had as much, if not MORE, to do with his family legacy standing the test of time.

On November 28, 1879, a cyclone struck the Crystal Springs Distillery. (As I explained yesterday, Fred Stitzel was in charge of the Crystal Springs Distillery at 1st and Magnolia Streets in old Louisville. He had been closely connected to the company since the early 1870s and had married the original owner’s daughter.) The extreme winds nearly destroyed the site. The still house was badly damaged and the smokestack was blown down. The distillery’s warehouse lost its south and western facing walls, and its roof was blown clean off. Frederick Stitzel narrowly escaped with his life after leaving the warehouse just moments before the cyclone hit and brought the walls down. A curious note in the newspapers was that only a few of the barrels in the collapsed warehouse had been damaged. Frederick’s famous patent for his barrel racking system had coincidentally been approved by the US patent office just three days earlier! While Frederick’s run-in with death was certainly a harrowing experience, the buildings were repaired and improved. Frederick would sustain other small injuries at Crystal Springs Distillery, but none as life threatening as what he’d experienced 5 years later.

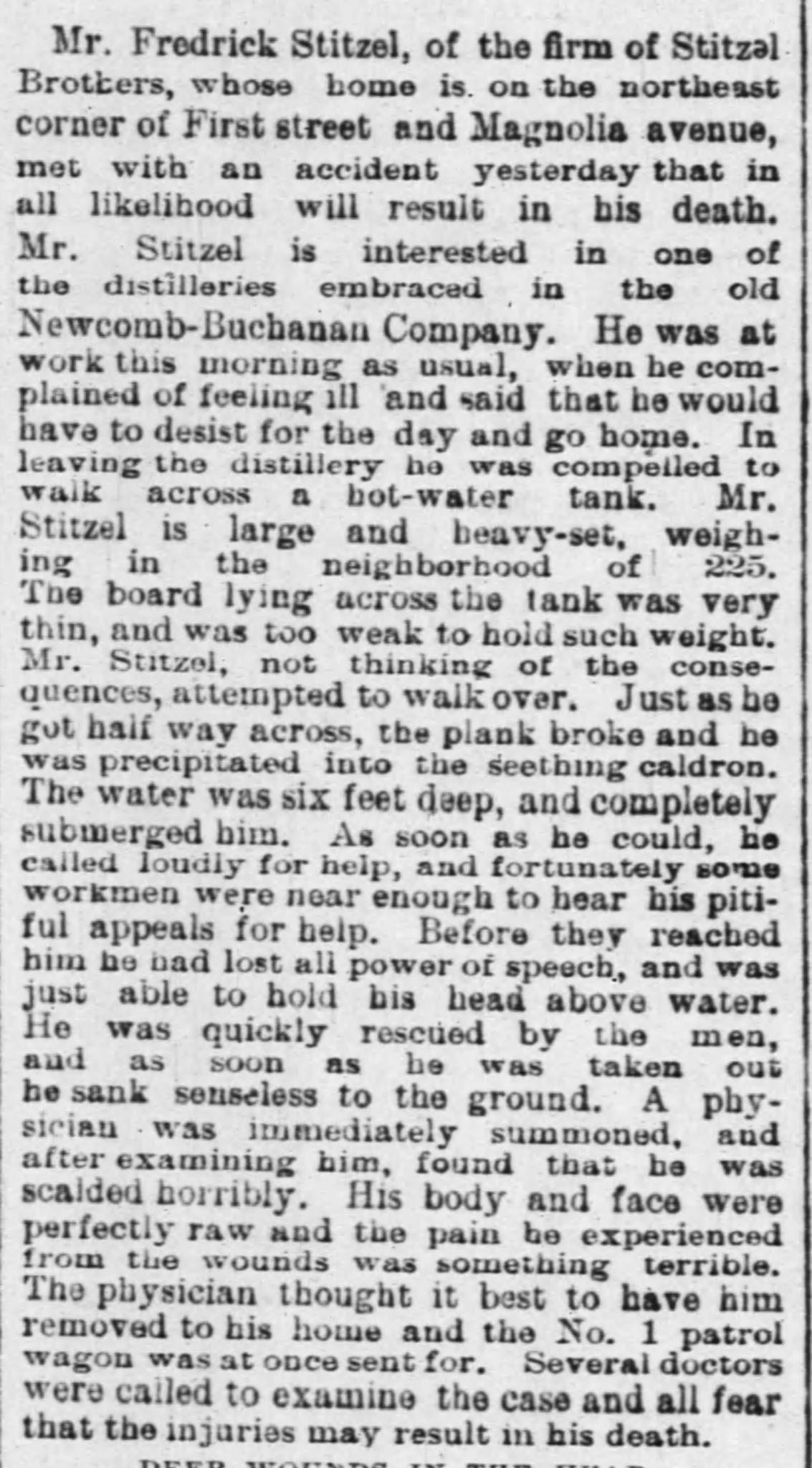

On May 18, 1885, Frederick, 42 years old and approximately 225 lbs., walked across a wooden beam stretched over a boiling tank of water. He’d probably done it a thousand times before, but that board collapsed under his weight that afternoon, dropping him into a 6-foot-deep boiling vat. He was pulled from the vat after his fellow workers heard his screams, but by the time he was pulled free, most of his body was scalded raw and his hair had nearly all come off. Doctors removed him to his home, which was thankfully beside the distillery on the same city block. Every visiting doctor warned that Frederick would not recover from his injuries, but he would prove them all wrong. He shared his home at 1st and Magnolia Sts. with nine women- including his wife, daughters, mother-in-law, and sisters-in-law. Suffice it to say, he was well looked after. Frederick would go on to live for almost another 40 years.

On May 18, 1885, Frederick, 42 years old and approximately 225 lbs., walked across a wooden beam stretched over a boiling tank of water. He’d probably done it a thousand times before, but that board collapsed under his weight that afternoon, dropping him into a 6-foot-deep boiling vat. He was pulled from the vat after his fellow workers heard his screams, but by the time he was pulled free, most of his body was scalded raw and his hair had nearly all come off. Doctors removed him to his home, which was thankfully beside the distillery on the same city block. Every visiting doctor warned that Frederick would not recover from his injuries, but he would prove them all wrong. He shared his home at 1st and Magnolia Sts. with nine women- including his wife, daughters, mother-in-law, and sisters-in-law. Suffice it to say, he was well looked after. Frederick would go on to live for almost another 40 years.

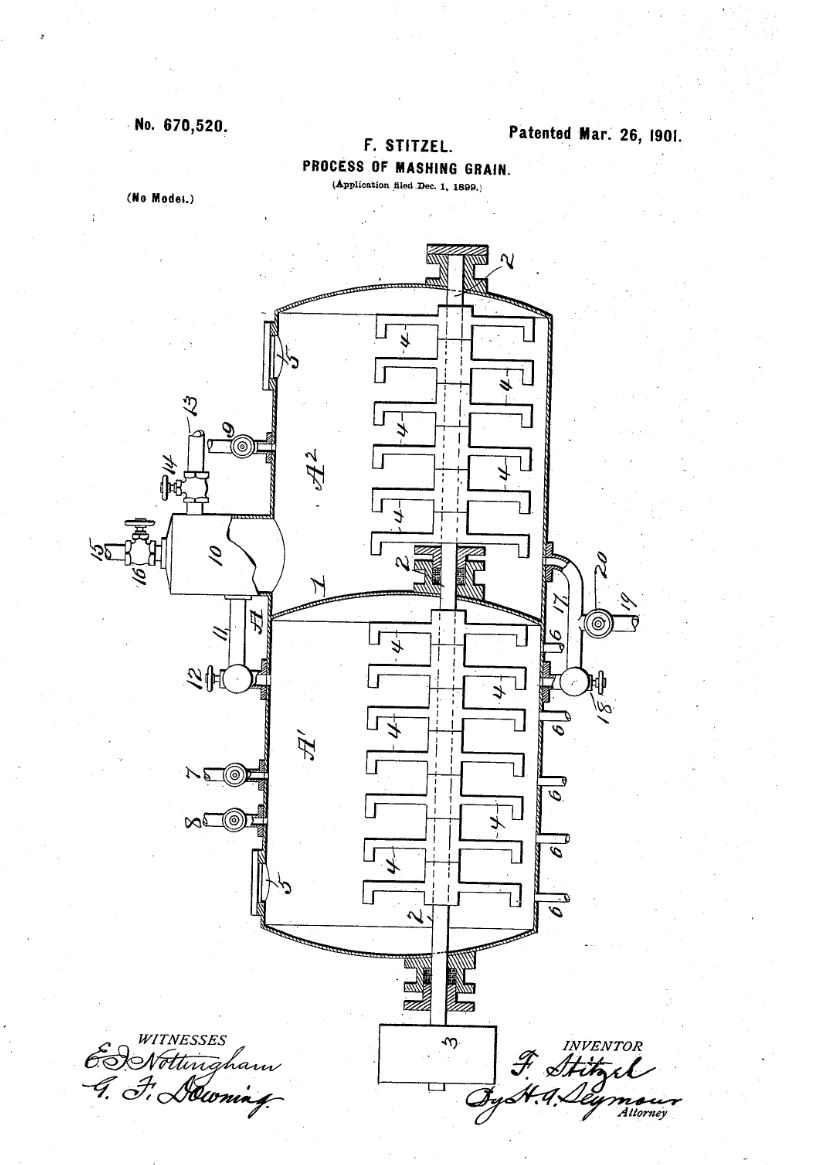

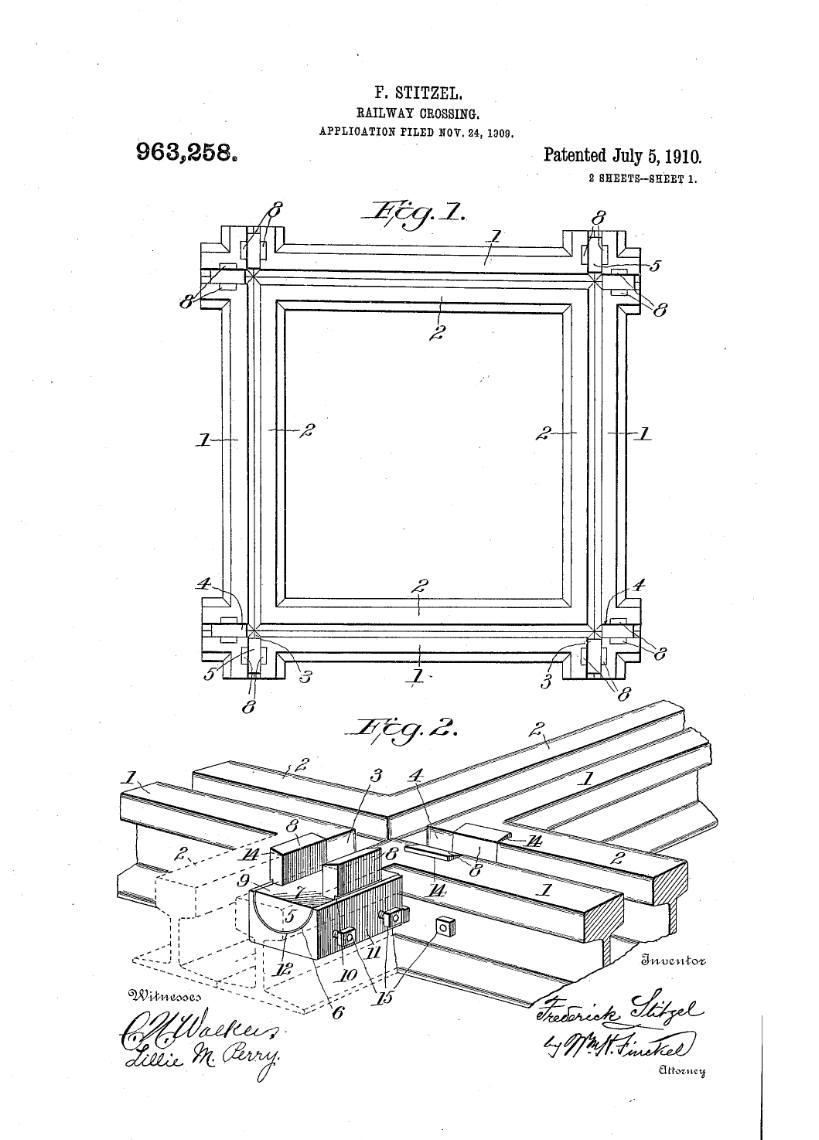

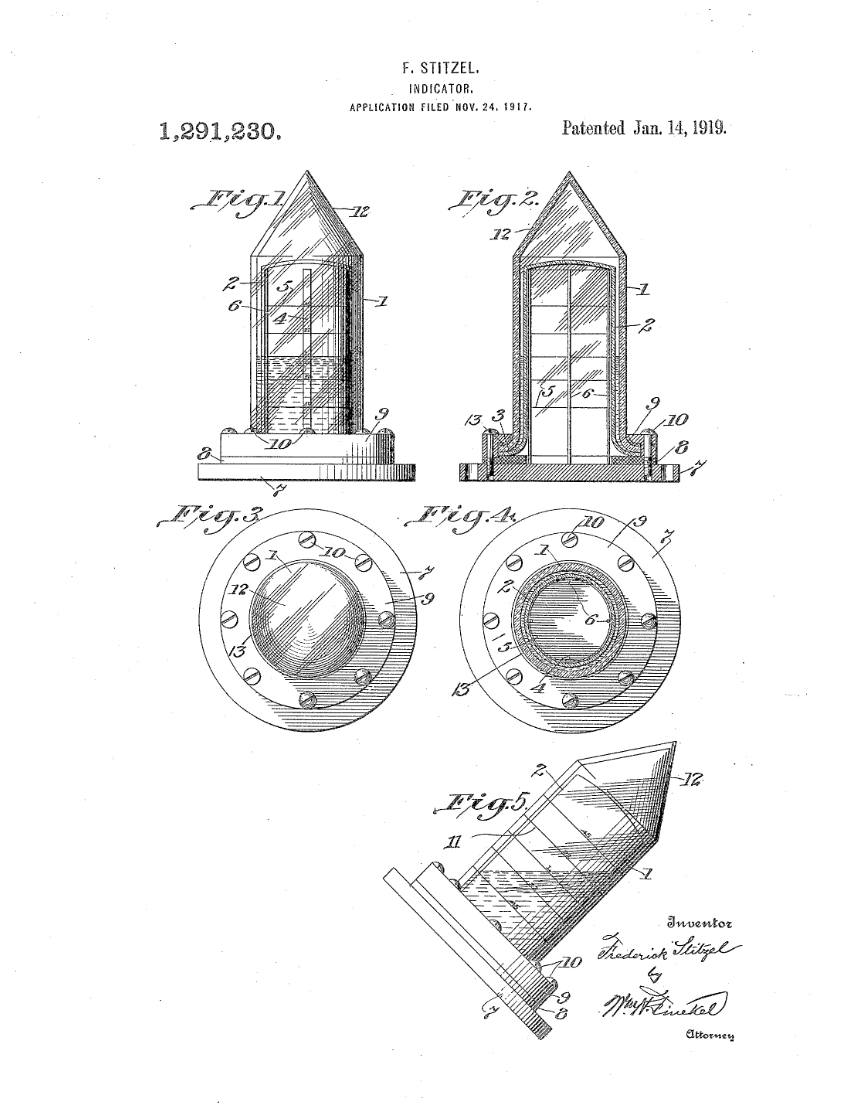

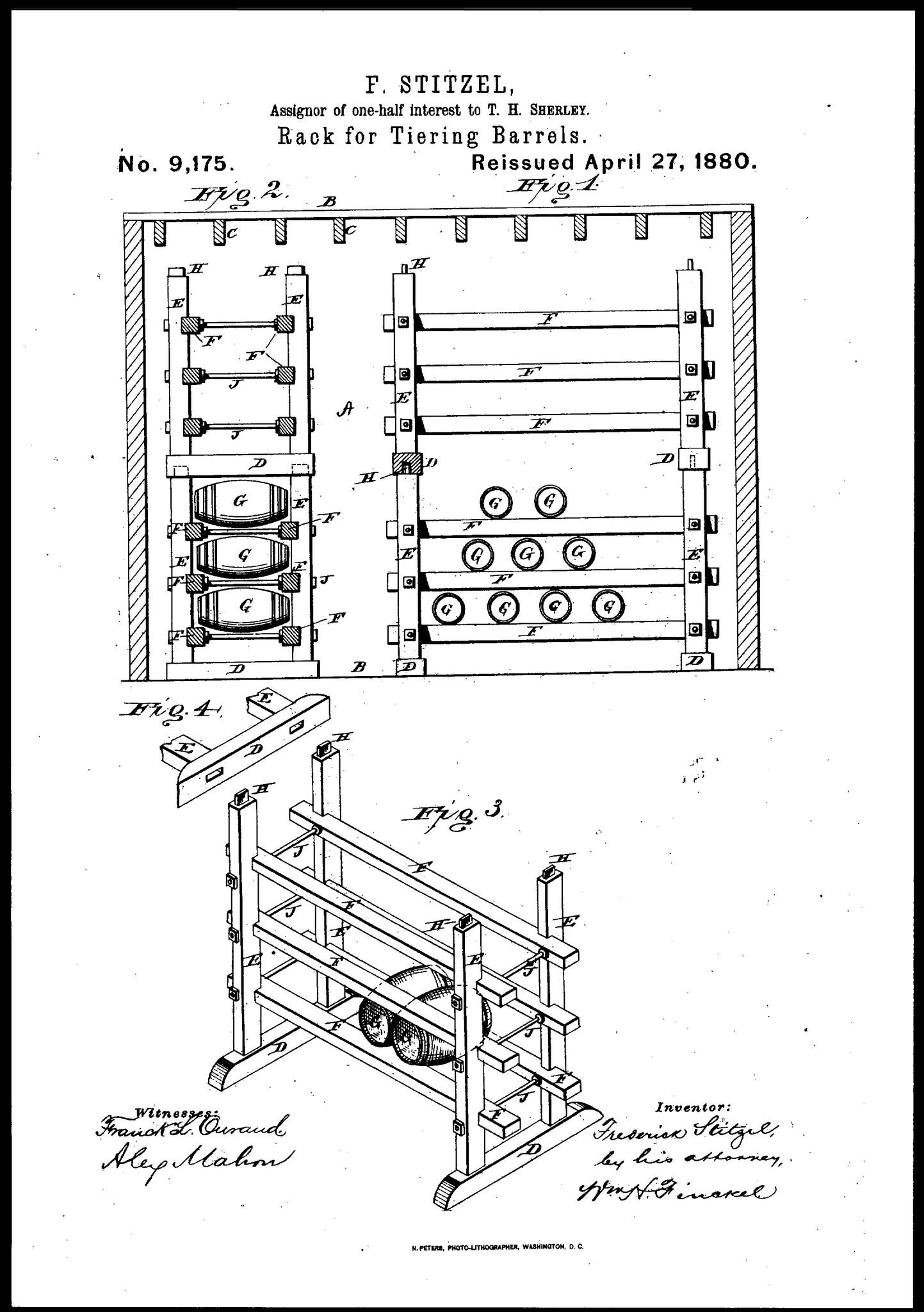

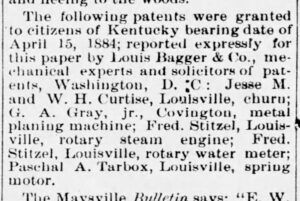

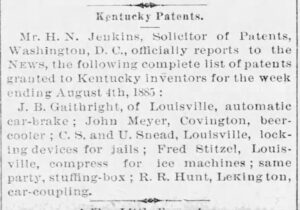

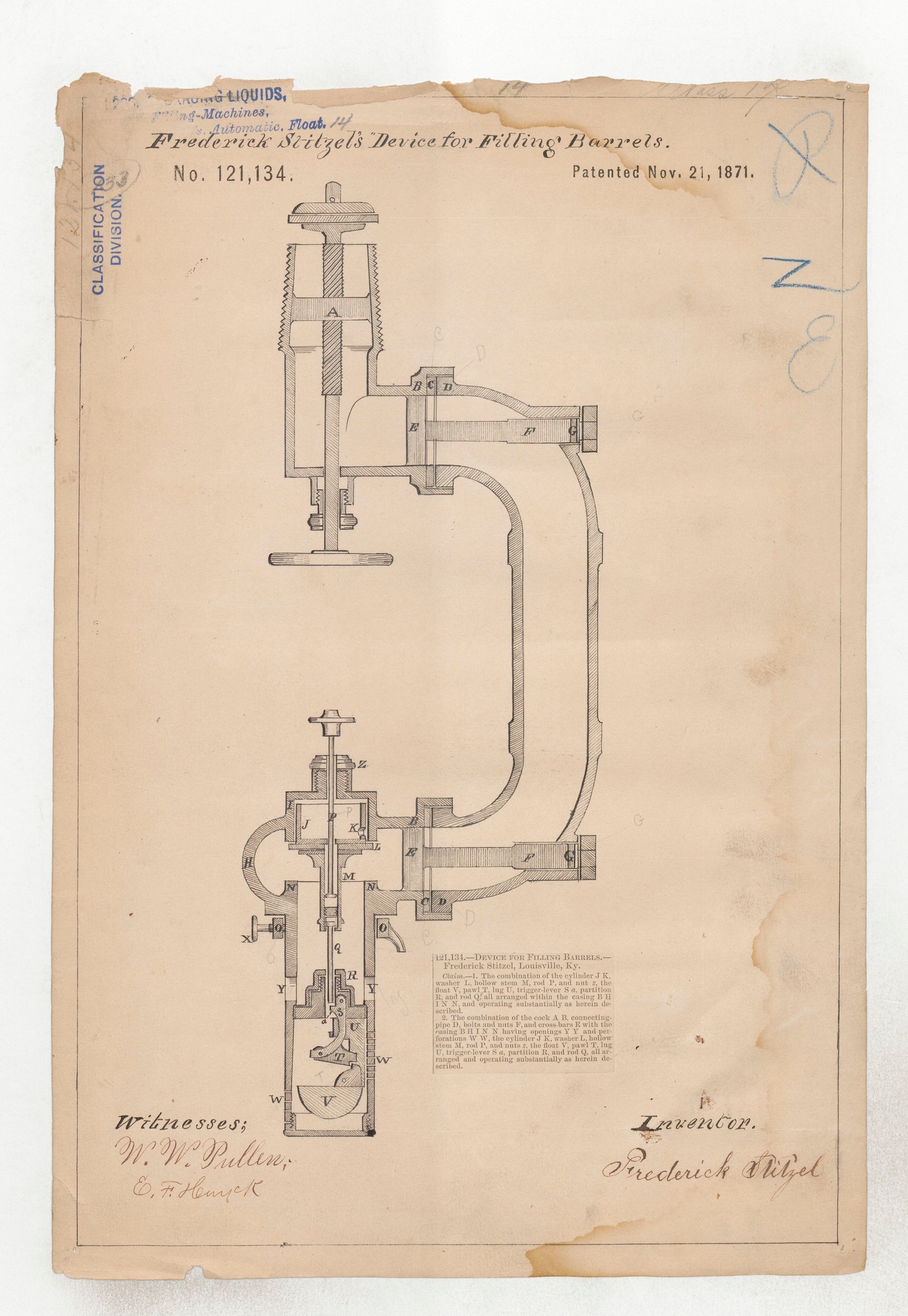

Frederick’s inventive business mind was not fazed by the accident. In fact, he seemed to become more committed to his inventions after the accident. While he recovered from his burns, he likely had plenty of time to think. No stranger to practical engineering, Frederick had been working with other inventors and applying for patents for his inventions for many years. While Fred Stitzel may be most often recognized by whiskey historians for his “rack for tiering barrels” patent in 1879, he had been an inventor throughout his life. 8 years before his barrel rack invention, he designed a method to improve the filling of barrels. He also invented his own patented process for speeding the maturation of whiskey.

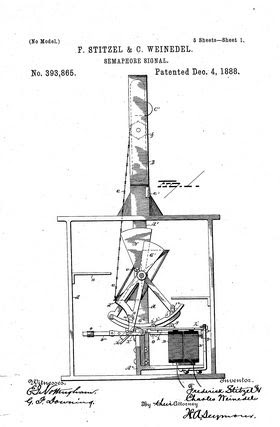

Arguably Frederick’s most impactful invention was his railroad semaphore. The patent for his invention was approved on June 29, 1886, just over a year after his scalding accident, but Frederick (and his partner, Charles Weinedel) had been tinkering with the concept for over 8 years. A semaphore is any apparatus used for signaling over long distances (flags, lights, fire, beacons, etc.). Frederick Stitzel designed a semaphore that could be installed by railroad companies along their tracks, helping engine drivers communicate while they’re still far enough away from one another to safely navigate the rails. On July 9, 1887, Frederick and his fellow patent holders incorporated the American Semophore Company with a capitalization of a million dollars. The invention of the railroad semaphore has been improved over time, but it vastly improved railroad safety- not just for passengers, but also for every bit of cargo that businessmen shipped by rail. Whiskey enthusiasts may remember Fred Stitzel for his barrel racks, but the nation remembered him for his semaphore. He would continue to invent for the rest of his life, adding dozens more patents to his list of personal achievements.

The Stitzel Distilleries- Part 4.

A Necessary Digression.

It is difficult to try to simplify the history of the whiskey industry in Kentucky. I have often found myself tied in knots whenever attempting to unravel who owned what and when. My research into American whiskey has been focused on Pennsylvania distilleries and the rye whiskey trade. Not an easy topic, obviously, but Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey distilleries were not bought, sold and traded the way that they were in Kentucky. New York, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Chicago…the liquor firms in America’s largest whiskey cities all wanted a piece of the bourbon trade. Distilleries became commodities and bonded warehouses became storage sites for America’s wealthiest liquor firms.

It is difficult to try to simplify the history of the whiskey industry in Kentucky. I have often found myself tied in knots whenever attempting to unravel who owned what and when. My research into American whiskey has been focused on Pennsylvania distilleries and the rye whiskey trade. Not an easy topic, obviously, but Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey distilleries were not bought, sold and traded the way that they were in Kentucky. New York, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Chicago…the liquor firms in America’s largest whiskey cities all wanted a piece of the bourbon trade. Distilleries became commodities and bonded warehouses became storage sites for America’s wealthiest liquor firms.

It’s important to note that America’s distilleries did not operate the way distilleries do today. A distillery was a production facility- a factory for whiskey production. Like any factory, a product was manufactured and sold in bulk to a customer that used it as a raw material for their own product. The whiskey they manufactured was made specifically for their customers- for liquor firms that bought their whiskey in bulk. Some of that whiskey was bottled “as was”, but most of it was altered in some way- usually as a straight whiskey blend or enhanced with additives and flavorings. Perhaps this description is not as romantic as we’d like it to be, but it doesn’t belittle the fact that some distilleries simply made better products than others, which made them very valuable. It’s difficult to imagine that distilleries were bought and sold as often as they were because we’ve come to think of our favorite old brands as being connected to specific historic distilling sites. While that was often the case in the 19th century, the 20th century shuffled the deck. One brand might be made at another site owned by the same company whose main offices were in New York or Cincinnati. While brands may have been founded by the families that built the distilleries in the first place (hence the matching names), those families usually had distribution networks with warehouses and offices in multiple US cities. As a brand changed hands, so did its bottling and distribution sites. Just because a whiskey was labeled as being “from Louisville” didn’t mean it was made there! It just meant it was distributed from there. We tend to think of distilleries today as being the owners of their own brands and the producers of their own whiskey, but even today, that is not always the case. Confusing, right? Try to think of it this way- Distilleries made whiskey. Liquor firms bottled, sold and distributed that whiskey.

Unfortunately, this shuffling of ownership in Kentucky helped to erode the value of individual production sites. In the late 1890s, this left bourbon distilleries vulnerable to consolidation. The Whiskey Trust scooped up about 90% of the distilleries in Kentucky in 1899. The members of the Trust were whiskey men from all over the country. They were the owners of the brands that the distilleries supplied. Unfortunately for the distilleries, the Trust understood that “the brand” was all that mattered. They could shut down the smaller distilleries they acquired and simply manufacture the whiskey they required in their largest facilities. The Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Company, a collection of the Kentucky distilleries that had been acquired by the Trust, became a subsidiary of the Trust’s umbrella company, the American Sprits Manufacturing Company. While it appears that everyone continued to operate as independent production facilities, the game had changed. There were independent production facilities that operated separately from the Trust, but they were under constant threat. The Trust manipulated prices and controlled the market, so it was necessary for independent firms to work together to maintain their place within the industry. This is where we return to the Stitzel distilleries. While the Trust swallowed up the original location of the Stitzel Brothers, the Stitzel family’s Story Avenue plant remained independent. This is where our story meets the Weller and Van Winkle timelines. But we’ll get to that…

The Stitzel Distilleries- Part 5.

The Glencoe Distillery.

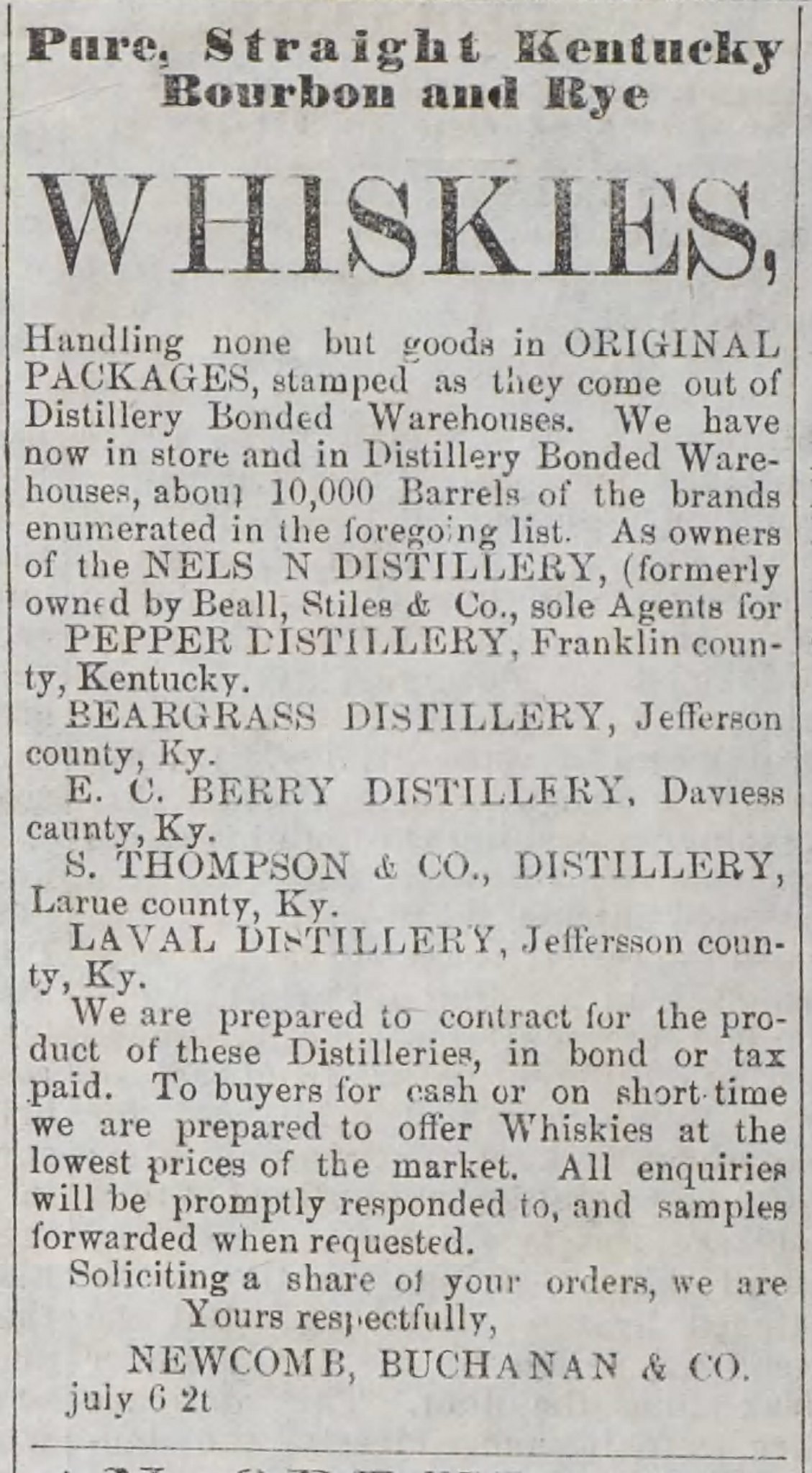

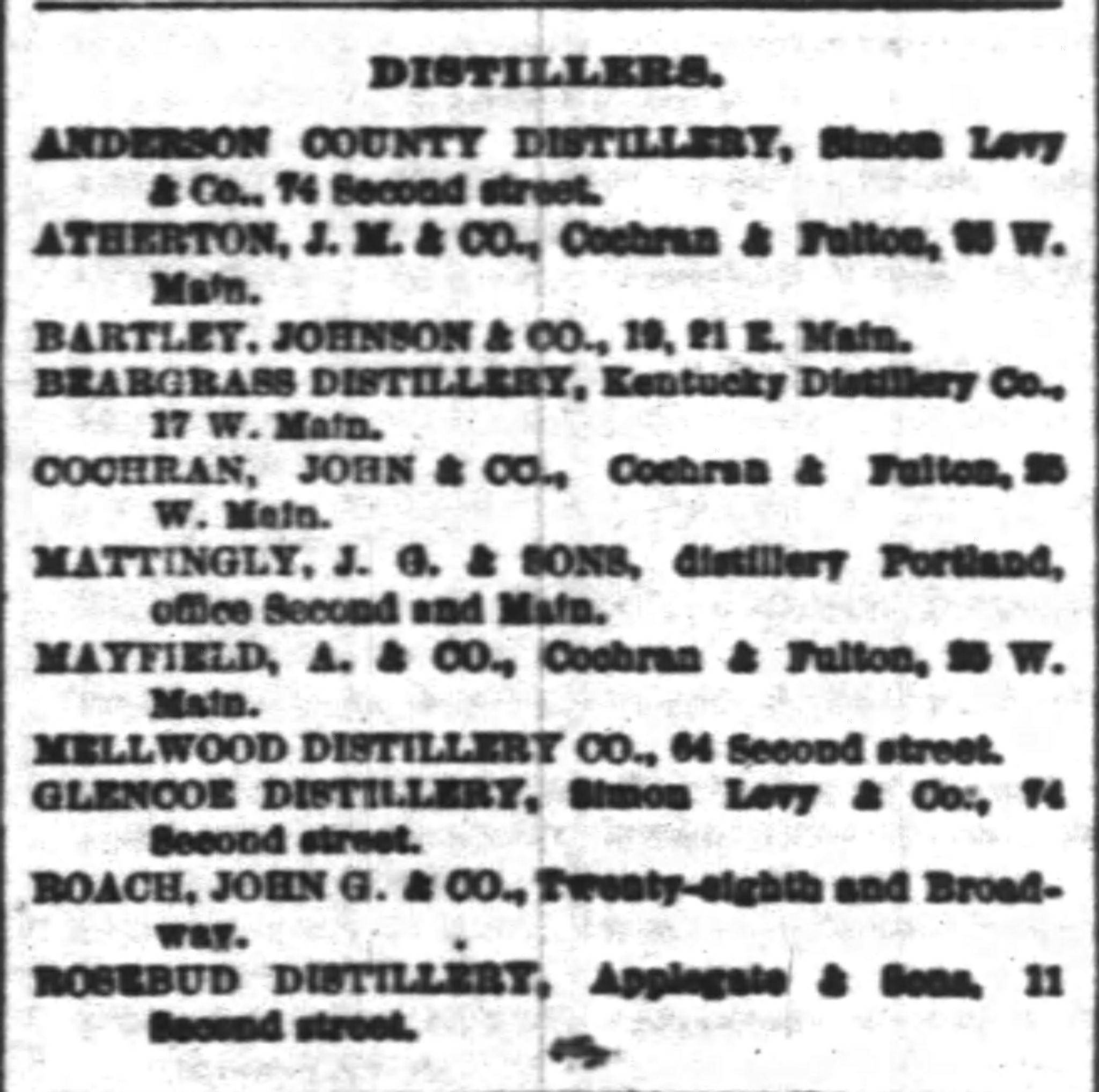

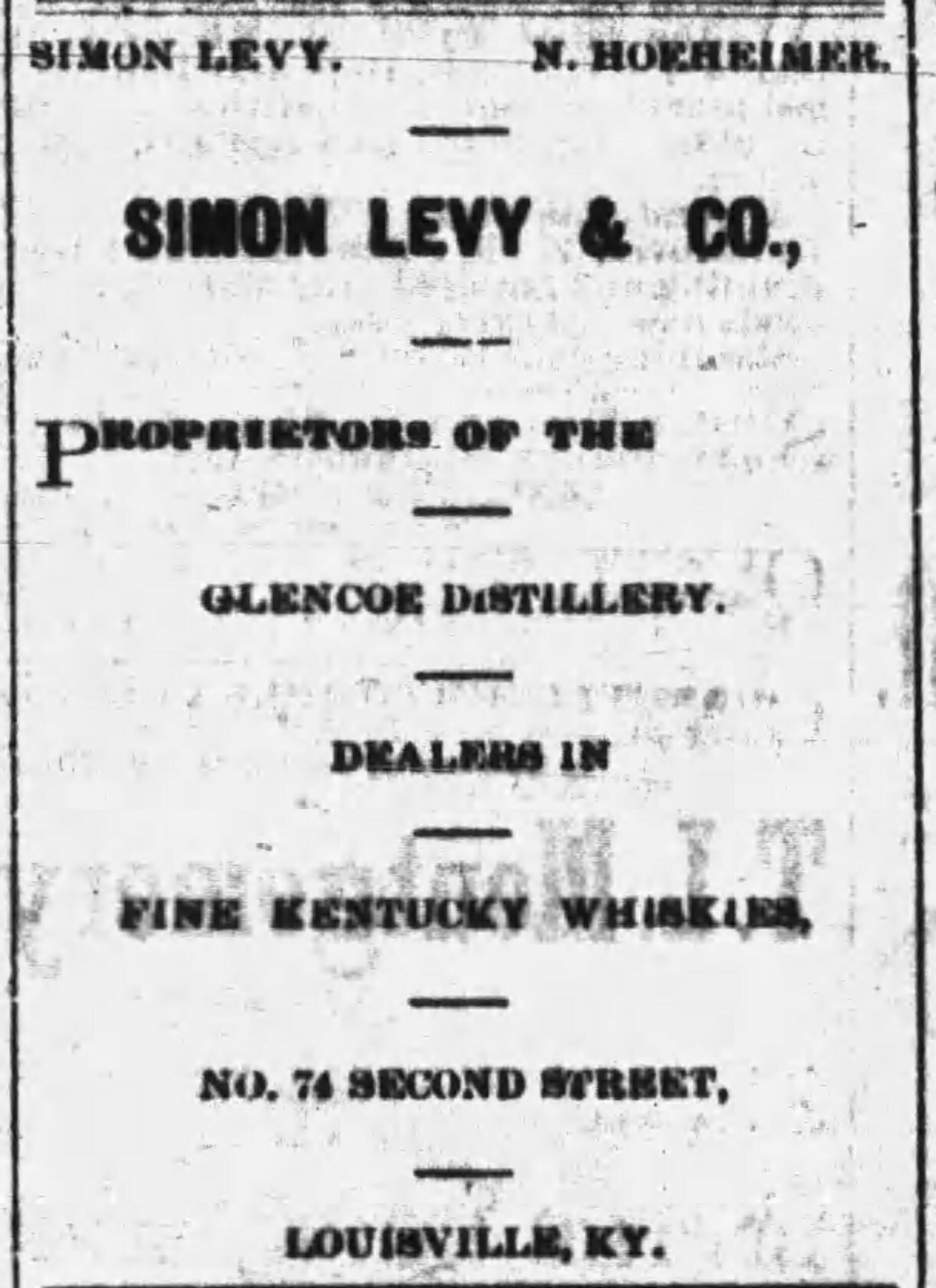

To put it simply, the Glencoe Distillery was the Stitzel Distillery at 26th and Broadway in Louisville. It’s hard to say with certainty where the name “Glencoe” came from, but the first liquor firm to use the name was Simon Levy & Co. of Louisville. Simon Levy’s partners were Nathan and Ernest Hofheimer of New York. The men managed a stand at 232 2nd Street and a retail store at 74 2nd Street in Louisville, but they also maintained satellite locations in other cities (Little Rock, Los Angeles, etc.), as well. In 1883, it appears that Simon Levy & Co. (or at least their rights to proprietorship of the Glencoe Distillery) was bought out by Phil Hollenbach & Co.’s retail establishment at 1st and Market Sts. in Louisville. Both Levy and Hollenbach’s brands were distilled by “the Glencoe Distillery.” While it is possible that both Levy and Hollenbach were referring to a rectifying establishment within their own wholesale locations, it’s more likely that they were referring to whiskey they purchased from the the Stitzel Bros. Distillery at 26th and Broadway. Early 1880s advertisements refer to both Simon Levy and Phil Hollenbach as “sole proprietors of the Glencoe Distillery”. (As I explained in Monday’s post, liquor firms were selling whiskey, not making it. The distillers of ‘Glencoe whisky’ were members of the Stitzel family even if the Glencoe brand was being marketed for sale by Levy or Hollenbach.)

To put it simply, the Glencoe Distillery was the Stitzel Distillery at 26th and Broadway in Louisville. It’s hard to say with certainty where the name “Glencoe” came from, but the first liquor firm to use the name was Simon Levy & Co. of Louisville. Simon Levy’s partners were Nathan and Ernest Hofheimer of New York. The men managed a stand at 232 2nd Street and a retail store at 74 2nd Street in Louisville, but they also maintained satellite locations in other cities (Little Rock, Los Angeles, etc.), as well. In 1883, it appears that Simon Levy & Co. (or at least their rights to proprietorship of the Glencoe Distillery) was bought out by Phil Hollenbach & Co.’s retail establishment at 1st and Market Sts. in Louisville. Both Levy and Hollenbach’s brands were distilled by “the Glencoe Distillery.” While it is possible that both Levy and Hollenbach were referring to a rectifying establishment within their own wholesale locations, it’s more likely that they were referring to whiskey they purchased from the the Stitzel Bros. Distillery at 26th and Broadway. Early 1880s advertisements refer to both Simon Levy and Phil Hollenbach as “sole proprietors of the Glencoe Distillery”. (As I explained in Monday’s post, liquor firms were selling whiskey, not making it. The distillers of ‘Glencoe whisky’ were members of the Stitzel family even if the Glencoe brand was being marketed for sale by Levy or Hollenbach.)

Phil Hollenbach began his business as a whiskey merchant and importer in Louisville in 1871. His consistent growth over the next decade was largely due to the popularity of the whiskey he had been sourcing from the Stitzel plant. When Phil Hollenbach assumed proprietorship of the Stitzel plant in 1883, Nathan Hofheimer of S. Levy & Co. was moving his interests to the Anderson & Nelson plants across town. (This move coincides with Frederick Stitzel’s connection to the same company.) By the late 1880s, Hofheimer became a buyer for English syndicates looking to acquire important Kentucky distilleries. (For more on this topic, click HERE) While Hofheimer was investing in the distilleries run by Newcomb-Buchanan, Phil Hollenbach was gaining control of the output of the Stitzel Distillery at 26th and Broadway.

In 1884, Phil Hollenbach partnered with Nace Vetter to form Hollenbach & Vetter. The partnership abandoned Hollenbach’s previous retail business, shifting their focus to the wholesale trade instead. Hollenbach & Vetter’s new salesroom was located at the northwest corner of 6th and Market Sts. in Louisville. Their sales of Glencoe whiskey stretched from Kentucky to California, and they were earning a stellar reputation as they went. To be clear, the reputations being built by these liquor dealers were built upon the excellence of the whiskey being manufactured by the Stitzel brothers. For Nathan Hofheimer, it was Frederick Stitzel’s whiskey being made at the Crystal Springs Distillery, a distillery owned by the Anderson & Nelson Distilleries group. For Phil Hollenbach, it was Jacob and Philip Stitzel who were busy making whiskey at the Stitzel plant at 26th and Broadway. Either way, the Stitzel men were boosting the reputations of Louisville’s liquor dealers.

In December 1889, the English syndicate buying distilleries through their representative, Nathan Hofheimer, had acquired 17 Kentucky distilleries. Among them were the Anderson and Nelson Distilleries (Anderson, Nelson, Laval/Crystal Springs, Beargrass Creek Distillery/Kentucky Distillery Co., the Pepper Distillery in Franklin Couty, the E.C. Berry Distillery in Davies Couty) as well as the Patterson and Atherton Distilleries of Louisville, the Ripy Distillery of Anderson County, the Old Lewis Distillery and the Megibben & Bramble Distillery- both in Lair, Ky, T.J. Megibben’s distillery in Cynthiana, among others…The consolidations of distilleries in Kentucky was already well underway. Frederick Stitzel at the Crystal Springs Distillery had a new boss. Again.

While all these consolidations were taking place, the rest of the Stitzel family continued to retain control of the output of their plant (Glencoe Distillery) at 26th and Broadway. Nace Vetter dissolved his partnership with Hollenbach & Vetter in 1888, leaving Phil Hollenbach as sole proprietor of the Glencoe Distillery. His independence would be challenged over the next decade, however, as a new power dynamic began shifting the landscape of Kentucky’s distilling industry. The Kentucky Distillers Association, which had been formed in 1880 by T.J. Megibben and John Callaghan (Cincinnati firm), was formed to lobby on behalf of Kentucky distilleries, but it was also managed by the people that were busy consolidating distilleries! A Whiskey Trust was taking shape in the West, but Kentucky’s liquor firms weren’t going down without a fight. The Kentucky distilling interests, eager to maintain their market share, followed the lead of their western competitors and created their own consolidated distilling companies. The trend seemed to imply that the bigger the firm, the more market share it could acquire and the less vulnerable it would become.

Unfortunately, business being business, the powerful firms began to see the benefits that came from consolidation- and those that didn’t want to be bought out were often forced into submission. By the late 1880s, the money was moving from Kentucky to the whiskey cities of the West- St.Louis, Peoria, and Chicago. Even when it seemed as if the Whiskey Trust’s power was being checked with anti-trust laws in the early 1890s, the Distilleries and Cattle Feeders Trust simply dissolved and restructured itself as a corporation with subsidiaries. The game hadn’t really changed; it just had new players. In August 1895, the old Whiskey Trust, based in Peoria, became the American Spirits Manufacturing Company, based in New York. Earlier that year, the Kentucky Distillers Association had also become a corporation. Its officers were R.N. Wathen (president), R. Monarch (vice president), Thomas S. Jones (secretary), and Fred W. Adams (treasurer). Fred W. Adams was secretary and treasurer of the Anderson & Nelson Distilleries Co. and associated with Fred Stitzel.

The Stitzel family and the Phil Hollenbach Company may have been able to resist the Whiskey Trust before, but its subsidiary, the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Co., was finally able to acquire the Glencoe Distillery at 26th and Broadway in 1902. It was, after all, right across the street from J.B. Wathen’s Distillery, one of the Trust’s crown jewel properties in Louisville. The Stitzel brothers, who had been working for Phil Hollenbach since 1883, had a new boss. Again.

The Glencoe Distillery continued to operate under the ownership of the American Spirits Manufacturing Company until it was closed by Prohibition. The distillery buildings were demolished in July 1924, but the brand would live on…without any connection to the distillery that made it famous. A new Glencoe Distillery would surface again in the 1930s- Louis Hollenbach built a new distillery at the corner of Cane Run and Campground Rds. The Hollenbachs would manufacture Glencoe and Fortuna whiskeys once again. It had been his brand since the 1880s, and Hollenbach would sell his new iteration of his old brand to a new generation of drinkers. The distillery was sold in 1943 to National Distillers and McKesson & Robbins. (Remember them?)

The Stitzel Distilleries- Part 6.

The Story Ave. Distillery.

I wanted to begin this post by saying that the history related to the Stitzel family that I have described thus far has had very little to do with the famous whiskeys manufactured at the Stitzel-Weller Distillery in Shively. I realize that heaps of marketing copy have helped to create a cult-like following for anything associated with Stitzel-Weller, but Stitzel-Weller was a POST-Prohibition distillery, built in 1935 about 10 miles away from the Stitzel brothers’ Story Avenue location. As I explained in the first part of this series on Stitzel, there were four Stitzel distilleries in Louisville- the first two near 26th and Broadway, the third at Story Ave. & Buchanan Sts., and the fourth in Shively (aka the Stitzel Weller Distillery). The last of the Stitzel brother distillers was Andrew Stitzel, and he passed away in 1935. In other words, the Stitzel-Weller’s master distiller, William McGill, did not learn to distill whiskey with the Stitzel brothers. McGill cut his teeth at the Felix G. Walker Distillery outside of Bardstown in the 1890s and worked for the Thomas Moore Distillery before Prohibition. He was an incredibly talented distiller of whiskey, but he was not a member of the Stitzel family. We’ll talk more about Stitzel-Weller soon, but I just thought it was important to make the distinction before going on. The distilleries and whiskeys that built the Stitzel legacy changed over time. To imply that there was ever a straight line connecting the Stitzel Brothers to Stitzel-Weller would be doing a disservice to the men who built the foundations of the company. Now, back to the Stitzels!

In 1902, the Whiskey Trust acquired the Glencoe (Stitzel) Distillery at 26th and Broadway. That same year, several other important events took place.

1. The Stitzel brothers (Frederick, Philip, Jacob, John, and Adam) lost their mother. Magdelena (Zoller) Stitzel died on February 20, 1902. She had outlived her husband, Dominick, by 28 years, but remained in Louisville with her sons and daughters until her death.

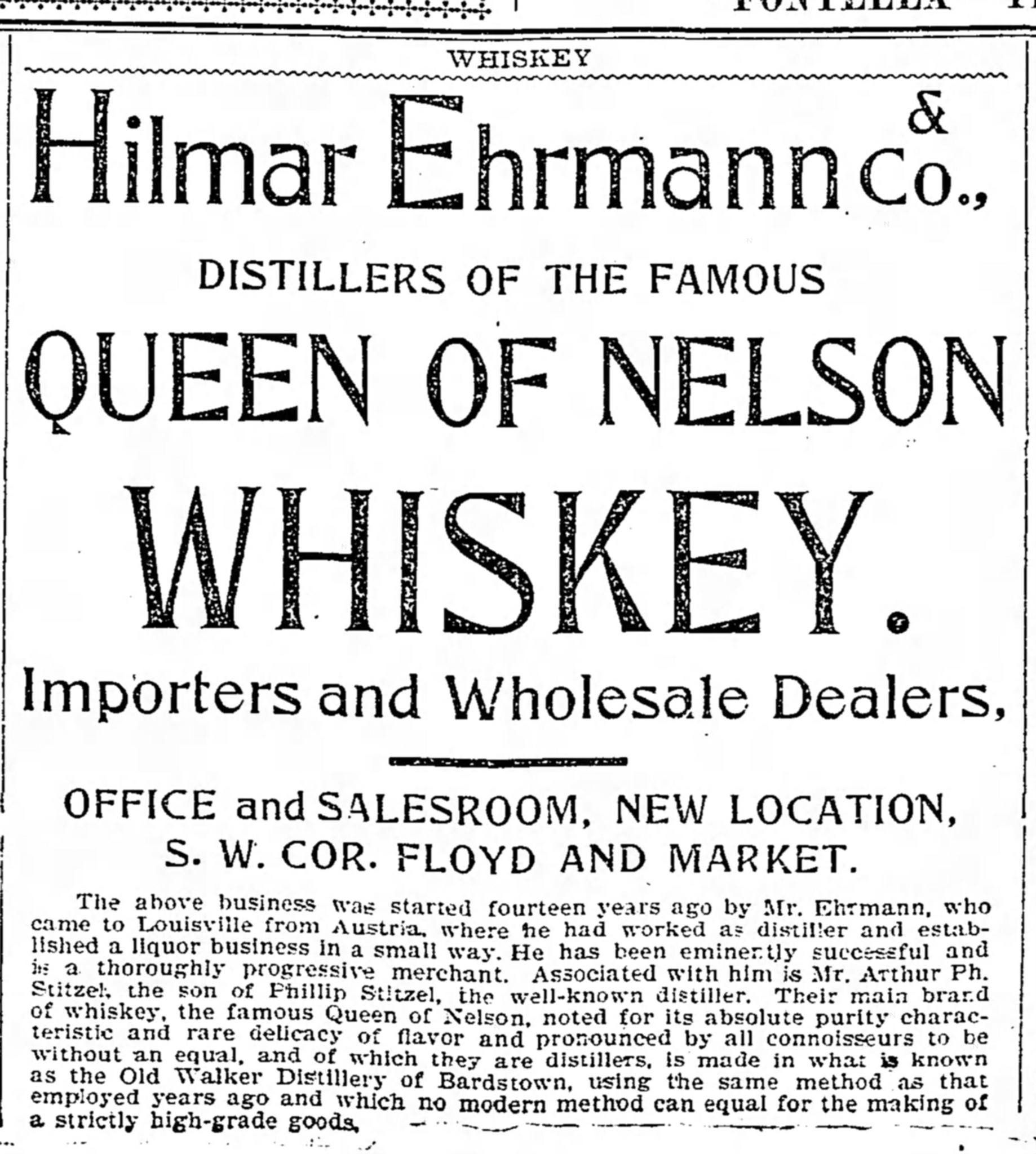

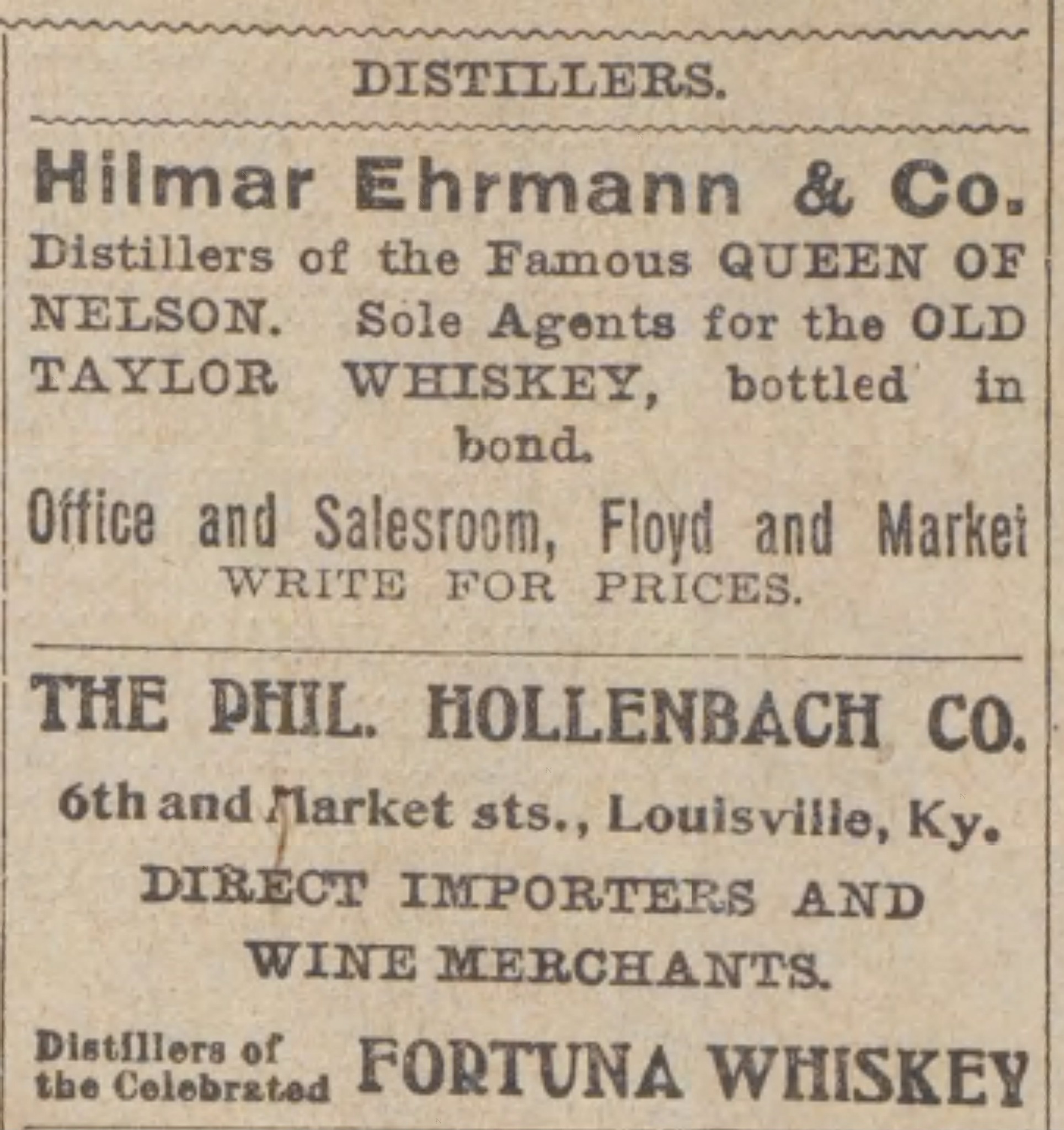

2. Philip Stitzel retired from active business. Arthur Philip Stitzel, 27-year-old son of Philip Stitzel, withdrew from the firm of Hilmar Ehrmann & Co., famous for their “Queen of Nelson” brand of sour mash whiskey. Arthur was drawn into a lawsuit for his departure, after serving less than 2 years of what was supposed to be a ten year partnership. Hilmar & Ehrmann bought most of their whiskey from Thomas B. Ripy’s distilleries in Bardstown. These neighboring distilleries were the T.B. Ripy/Old Walker Distillery, RD #112 and the Clover Bottom Distillery, aka Waterfill Dowling & Co. RD #418. Both distilleries were connected to the Anderson & Nelson Distilleries Co., so it makes sense that A.Ph. Stitzel found a place within the Hilmar Ehrmann Co., even if it was short lived. It appears he left the company to assume a place within the Stitzel Brothers Company after his father, Philip Stitzel, retired and the new distillery in Louisville was complete.

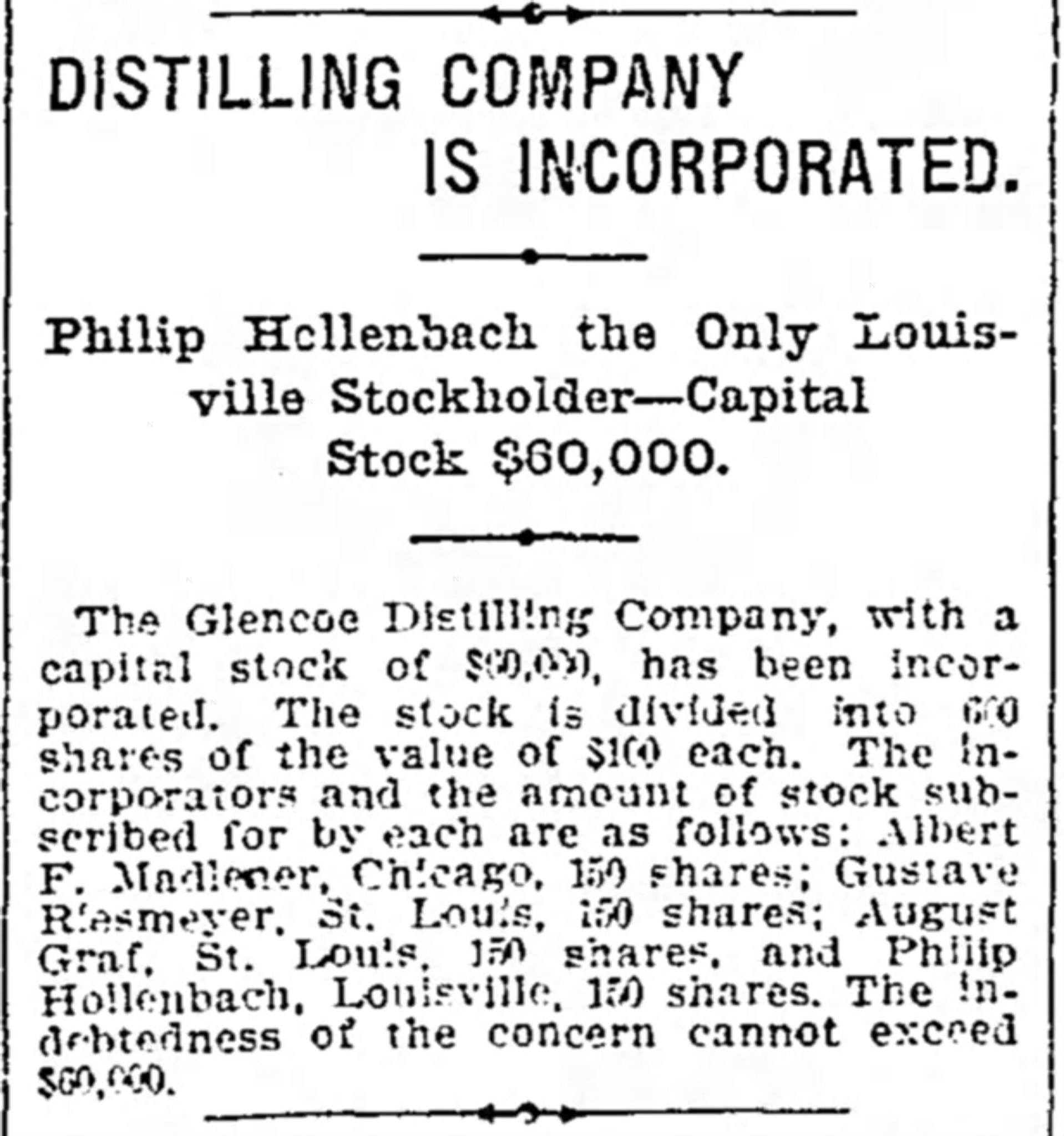

3. In June 1902, The Glencoe Distillery Company was incorporated in Jefferson County by four whiskey men- Albert F. Madelener of Chicago, Gustav Reismeyer and Gustave Graf, both of St. Louis, and Phil Hollenbach of Louisville. This incorporation effectively allowed Phil Hollenbach to retain his ownership of the brand he built. He continued to manage production at the Glencoe Distillery on 26th and Broadway, ownership of the plant had been passed to the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company.

4. In July 1902, Phil Hollenbach & Co. at 6th and Market Steets in Louisville, which would be celebrating its 25th anniversary the following year, incorporated with the following officers: Phil Hollebach as president, Edward Oesterritter as vice-president, Louis J. Hollenbach as secretary and treasurer, and Jake Hattemer as superintendent of the wine vaults. (It’s important to make the distinction between being a distillery owner and being a distilling company owner.)

5. The Stitzel brothers (Frederick, Philip, and Jacob) built a new distillery at Story Ave and Buchanan St. in Louisville, across town from their original location. This new Stitzel-owned property carried the family’s legacy forward. It appears that Andrew Stitzel, youngest of the Stitzel brothers, remained with the original plant which had been absorbed by the Whiskey Trust. John Stitzel was still with the Anderson & Nelson Co., also absorbed by the Trust.

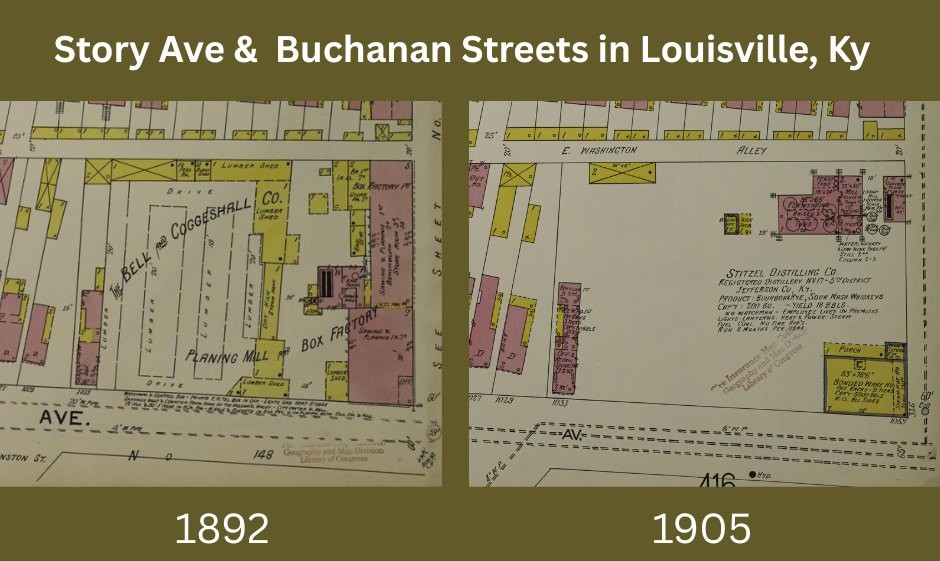

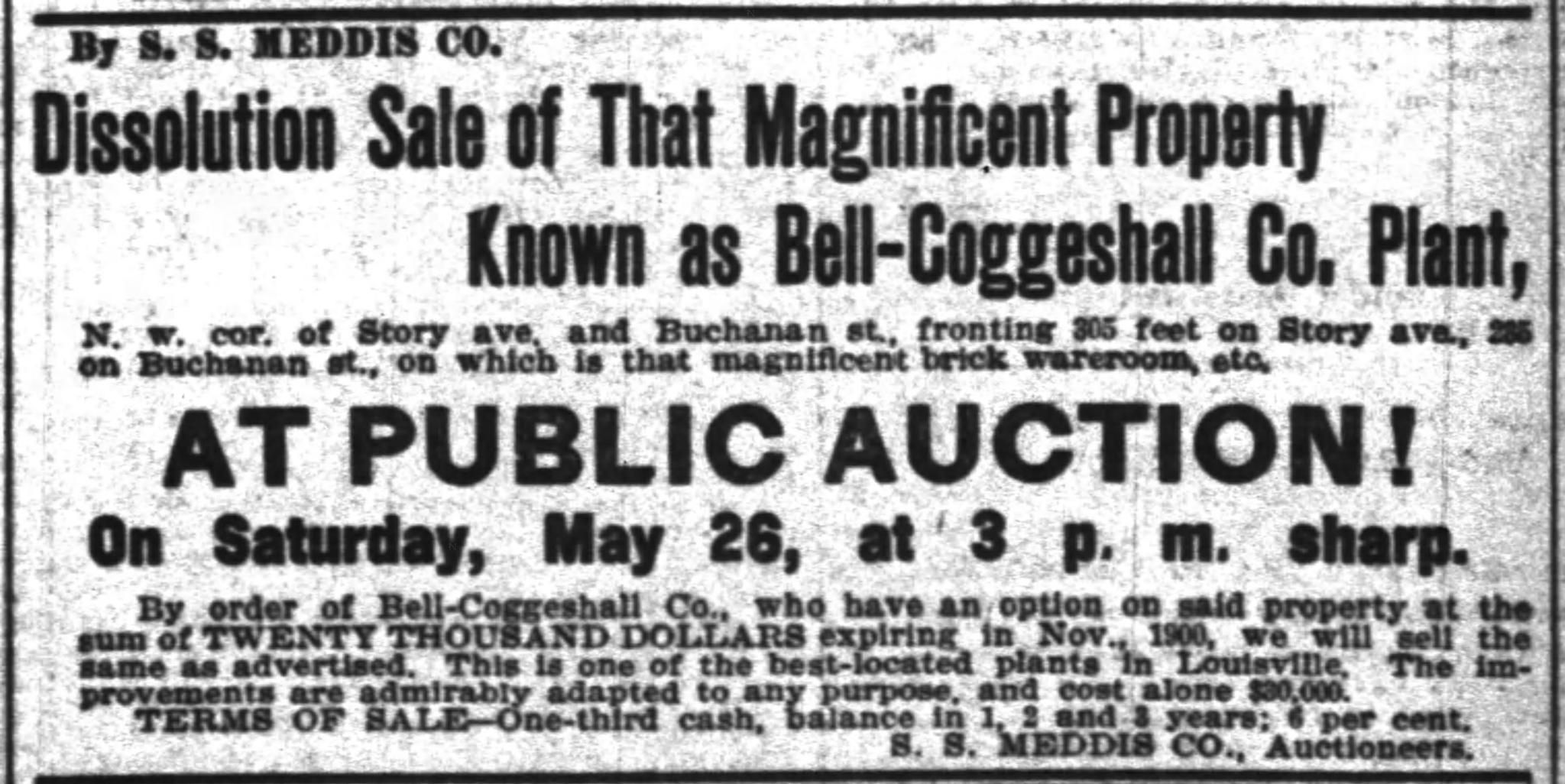

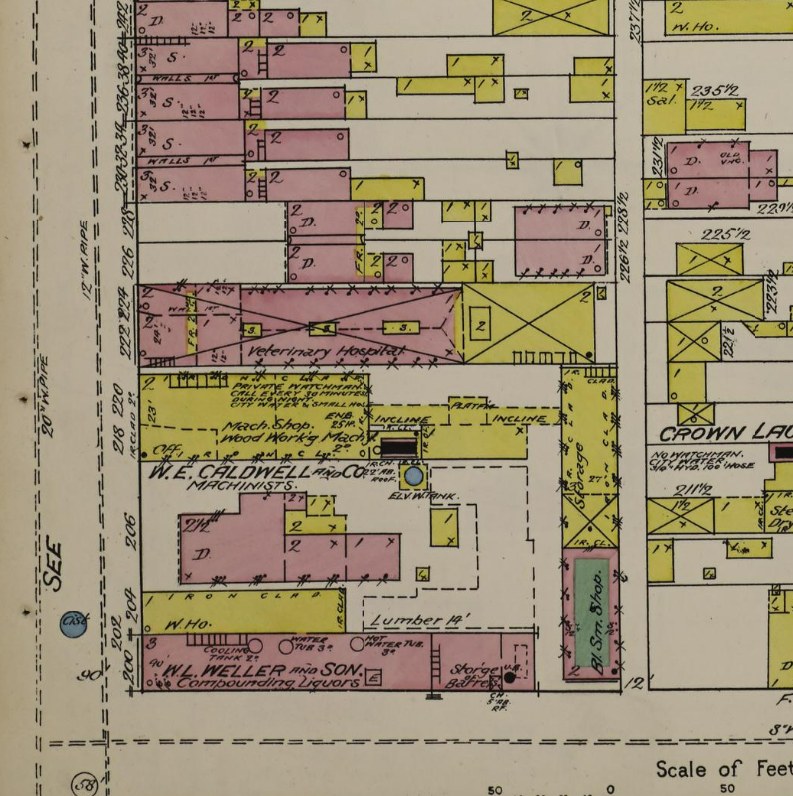

The new Story Ave plant was built on the site where Louisville’s Bell-Coggeshall Company had been until 1901. Bell & Coggeshall had been a planing mill and wooden box factory. They had a fine reputation for supplying lumber to build homes in and around Louisville and for supplying shipping crates for everything from whiskey to dry goods. While some histories describing the Stitzel Distillery on Story Ave. have the construction of the new plant taking place in the 1890s, that would have been impossible until Bell & Coggeshall moved their business to 16th and Lexington Aves in 1901. The site was a contentious one because of its location.  Rival cattle stock yard companies (Bourbon Stock Yards of Louisville vs. Union Stock Yards of Chicago) wanted access to the Louisville & Nashville railroad lines that neighbored the property. Several lawsuits involving access to the railroad were filed between 1899 and 1901. It’s curious to see the Stitzels gain ownership of the property in the end, but perhaps not so surprising when you take into consideration their connections within the city. The Story Ave plant continued to supply whiskey for Ph. Hollenbach & Co., Glencoe Distillery Co., and W.L. Weller & Sons (perhaps others?).

Rival cattle stock yard companies (Bourbon Stock Yards of Louisville vs. Union Stock Yards of Chicago) wanted access to the Louisville & Nashville railroad lines that neighbored the property. Several lawsuits involving access to the railroad were filed between 1899 and 1901. It’s curious to see the Stitzels gain ownership of the property in the end, but perhaps not so surprising when you take into consideration their connections within the city. The Story Ave plant continued to supply whiskey for Ph. Hollenbach & Co., Glencoe Distillery Co., and W.L. Weller & Sons (perhaps others?).

Philip Stitzel died in 1904 at the age of 58 from heart trouble. Philip, Dominick’s second son after Frederick, had always been a big part of the company. Frederick was distilling at Crystal Springs and doing business with several firms, but Philip seemed to be the rock that kept the Stitzel Distillery at 26th and Broadway running smoothly. The sale of the original site to the Whiskey Trust in 1902 sent him into retirement, but not before organizing the Stitzel Distilling Company and overseeing the construction of its new production facility on Story Ave. Philip’s only son, Arthur Philip Stitzel, would attempt to fill his father’s shoes within the company. Arthur had the experienced guidance of his uncles, so his transition into his role went rather smoothly.

In 1906, the Ryeland Distilling Company was incorporated with $20,000 capital stock. Its incorporators were Joseph J. B. Nienaber (Covington, Ky), Arthur Philip Stitzel, and Philip Julius Stuetzel (A. Ph. Stitzel’s cousin from Minnesota- the branch of family that settled in the west had a slightly different spelling.) Philip J. Stuetzel had been working for the German Insurance Bank in Louisville before going into business with his cousin. The next generation of the Stitzel family was feeling its oats. A. Ph Stitzel would be the one to carry the torch for his father and uncles. The family’s Story Avenue distillery would survive decades longer than the family’s original site at 26th and Broadway.

In 1906, the Ryeland Distilling Company was incorporated with $20,000 capital stock. Its incorporators were Joseph J. B. Nienaber (Covington, Ky), Arthur Philip Stitzel, and Philip Julius Stuetzel (A. Ph. Stitzel’s cousin from Minnesota- the branch of family that settled in the west had a slightly different spelling.) Philip J. Stuetzel had been working for the German Insurance Bank in Louisville before going into business with his cousin. The next generation of the Stitzel family was feeling its oats. A. Ph Stitzel would be the one to carry the torch for his father and uncles. The family’s Story Avenue distillery would survive decades longer than the family’s original site at 26th and Broadway.

The Stitzel Distilleries- Part 7.

The Family Tree.

Thought I’d share the family tree I compiled on the Stitzel family. I was asked how I keep everyone straight, and, well, this is how😊 I like to mockup family trees as I research so I can organize how individuals fit into the historic narrative. Dates and timelines can become confusing, but knowing who everyone is and where they fit in the family can be very helpful. This information is drawn from concrete sources- burial plots and cemetery records, obituaries, death certificates, marriage certificates, census records, immigration forms, military enlistment cards, city address listings, etc. Newspaper clippings, because they can be unreliable and full of typos, are always cross-checked against other (more reliable) sources. This is all based on information I have collected. I hope it’s helpful to anyone else looking at the history of the Stitzel family. The family tree is not overly detailed- it is just used as a quick reference for my own use- but, you’d be surprised how often I need to go back and check it (and update it!). If anyone has notes or insight into this family tree, please feel free to share!

The way I see it, people are what make American whiskey history interesting. Real people made real whiskey and built real legacies for their families- legacies that remain with us to this day! Reducing these real people into marketing blurbs or props to sell brands feels false somehow. I enjoy the opportunity to set the record straight- or at least as straight as I can get it! I find American whiskey distillers endlessly interesting! Even if history’s distillers are no longer with us, their stories provide touchstones for modern whiskey distillers and lend authenticity to old whiskey brands for consumers (even if the new brand versions are completely unrelated). The histories of distillers like the Stitzels help to reveal the complexities of the industry and provide context for the larger picture of what the industry was like during their lifetimes.

The Stitzel Distilleries- Part 8.

W.L. Weller & Sons.

While the Stitzel brothers were establishing themselves as respected distillers in Louisville during the 1870s and 80s, the Weller family had been building their own reputation as rectifiers. The two businesses, other than the fact that they were both within the city of Louisville, were unrelated to one another. That’s right. Unrelated. The only connection to speak of before Prohibition was through Weller & Sons’ association with the Whiskey Trust which purchased the Stitzel Distillery at 26th & Broadway in 1902. I could not find any proof that the Wellers sourced from the Stitzel Distilleries at all. Their connection happened after 1920. Odd as it may seem, it was Prohibition that brought them together.

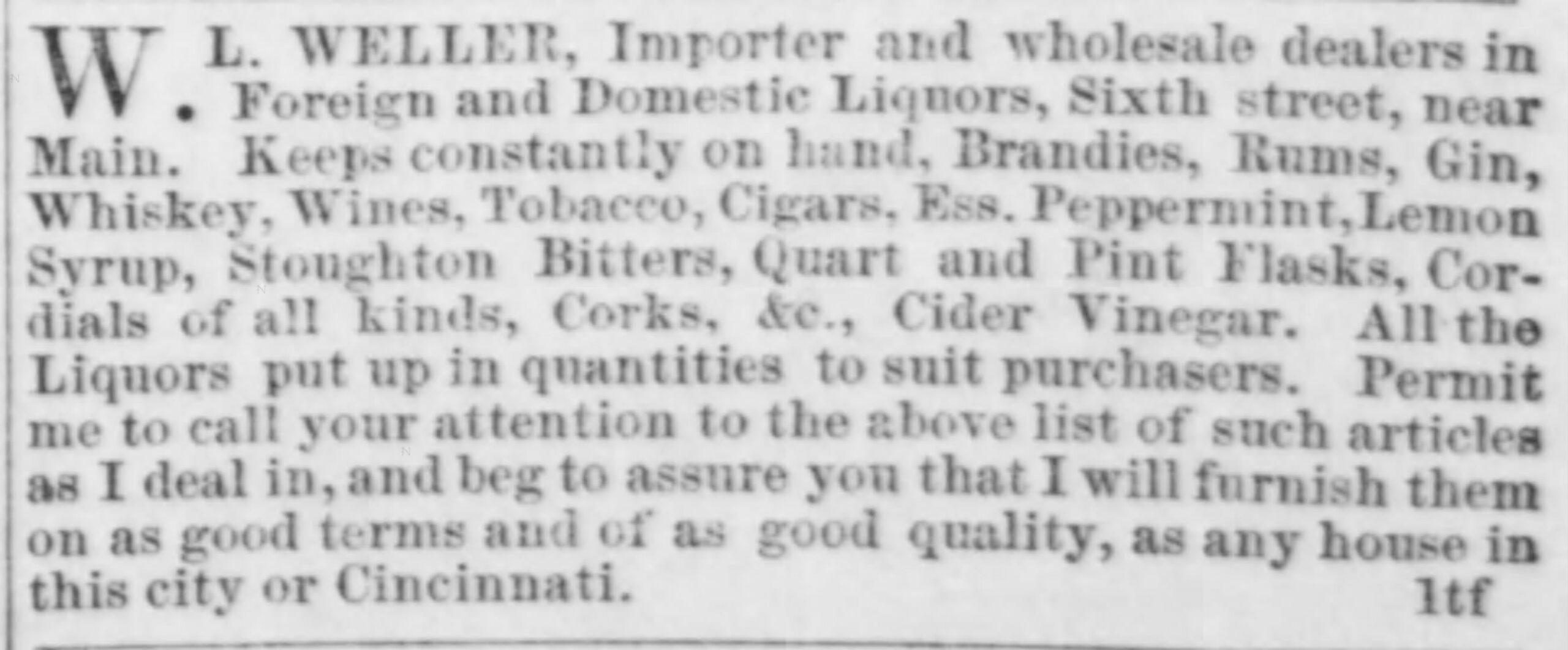

The Stitzel Distillery at 26th and Broadway was founded in 1872, while W.L. Weller & Son had been founded almost a quarter century earlier (1849) and represented one of the oldest liquor houses in Louisville. The location where William Lerue Weller built his business with his son, George P. Weller, as W.L. Weller & Son was located at Brook and Main Streets. (Today, that site is a small parking lot.)

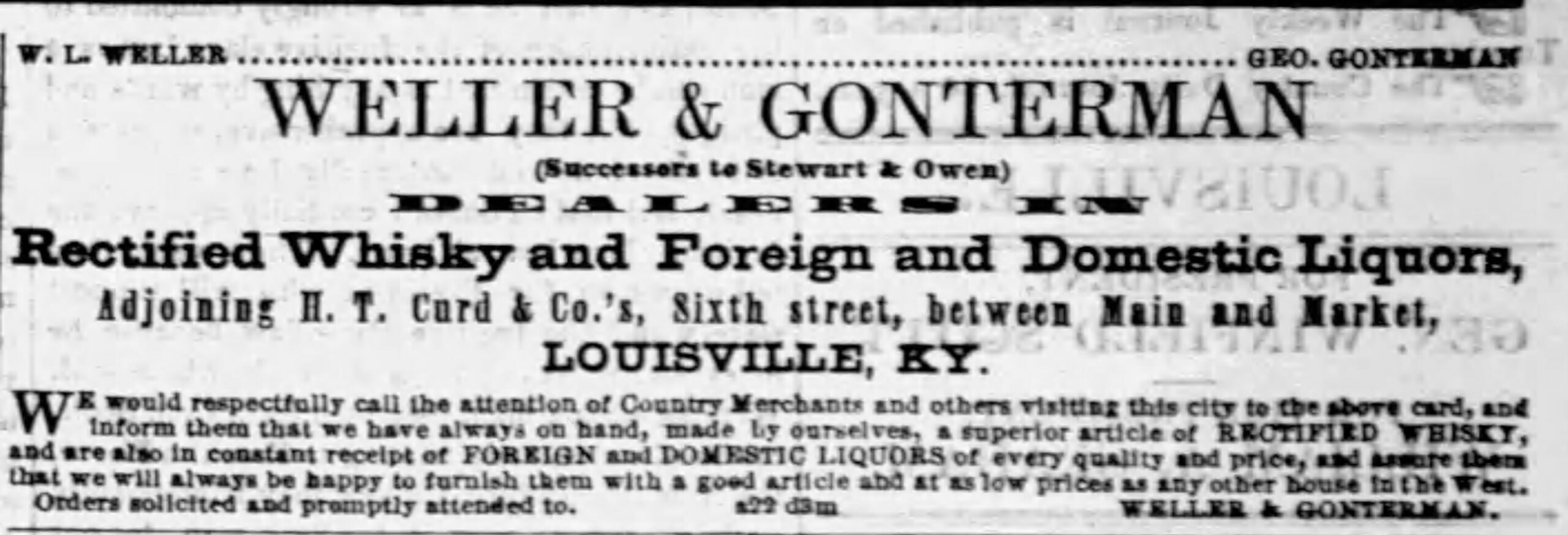

William Lerue Weller was born in Lerue County on July 26, 1825, son to Samuel and Phoebe (LaRue) Weller. (His grandfather founded LaRue County.) He came to Louisville when he was 19 years old, and enlisted in the Louisville Legion during the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). After returning from his deployment, he married Sarah B. Pence (1850) and became involved in the local liquor trade.  In 1852, William partnered with George Gonterman. The two men were successors to Stewart & Owens, a successful wholesale firm in Louisville that handled everything from liquor to coffins.

In 1852, William partnered with George Gonterman. The two men were successors to Stewart & Owens, a successful wholesale firm in Louisville that handled everything from liquor to coffins.

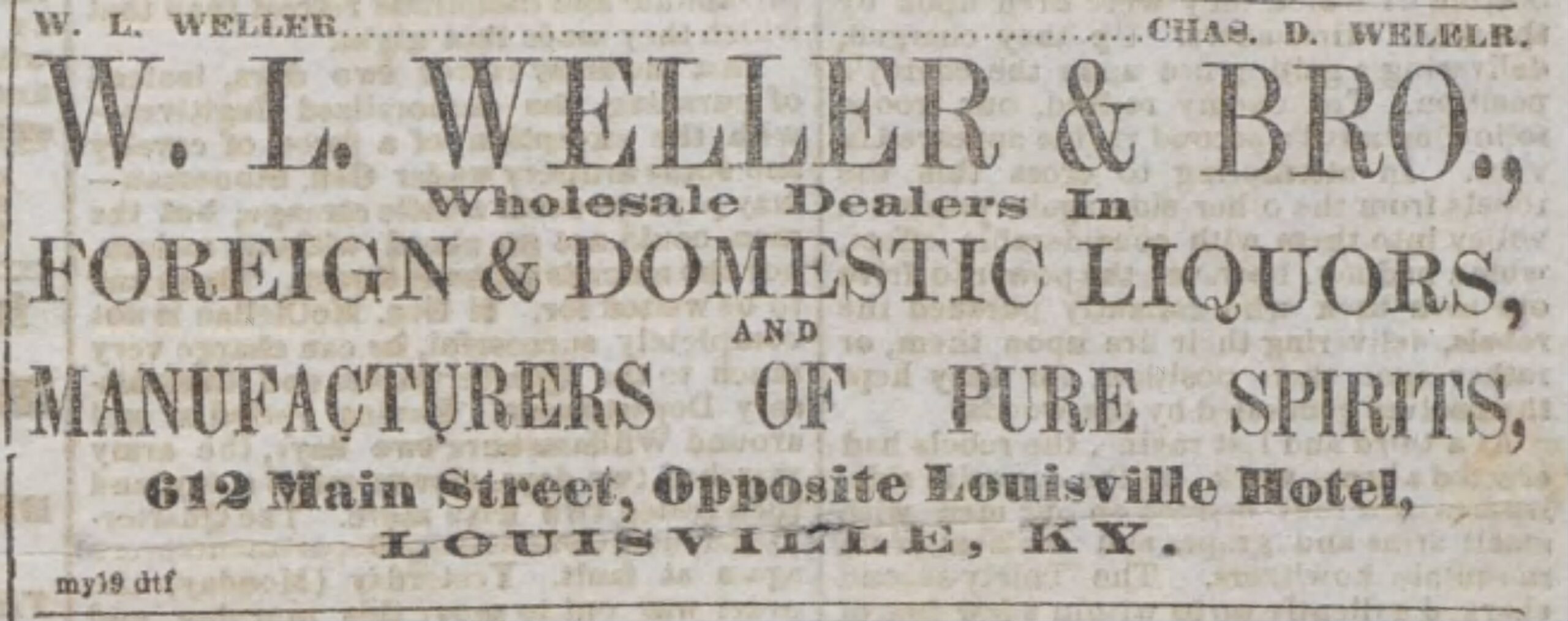

By the mid-1850s, the wholesale store on 6th Street between Main & Market (1st belonging to Stewart & Owen and then to Weller & Gonterman) was listed as simply “W.L. Weller”. William’s brother, Charles David Weller, joined the firm in 1860, which changed the firm’s name again to “W.L. Weller & Bro.” Unfortunately, Charles died on July 1, 1862 while serving as a soldier for the Confederacy. (An ad with his name as co-partner of “W.L. Weller & Bro.” was printed in the Louisville Daily Express less than two weeks before his death.)

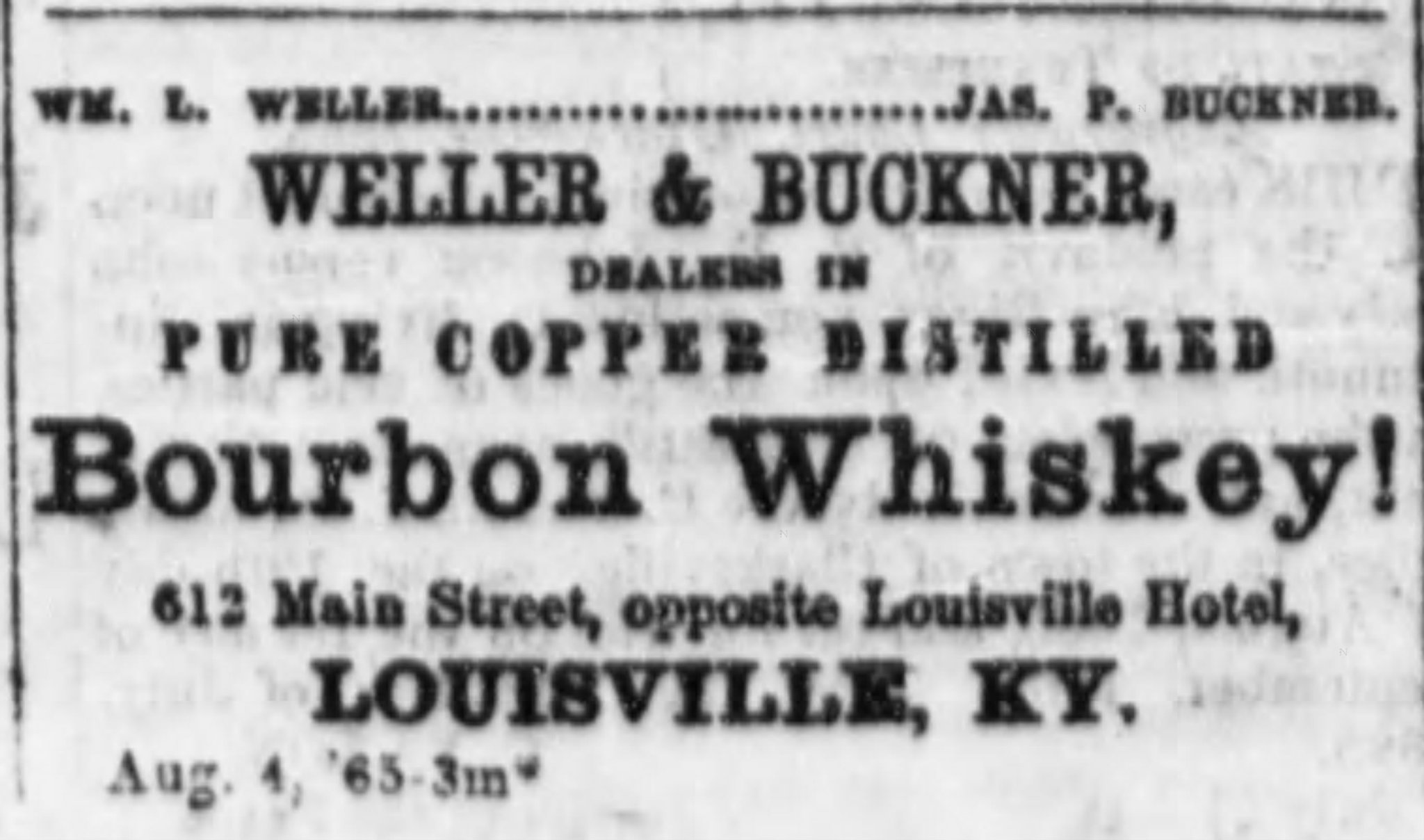

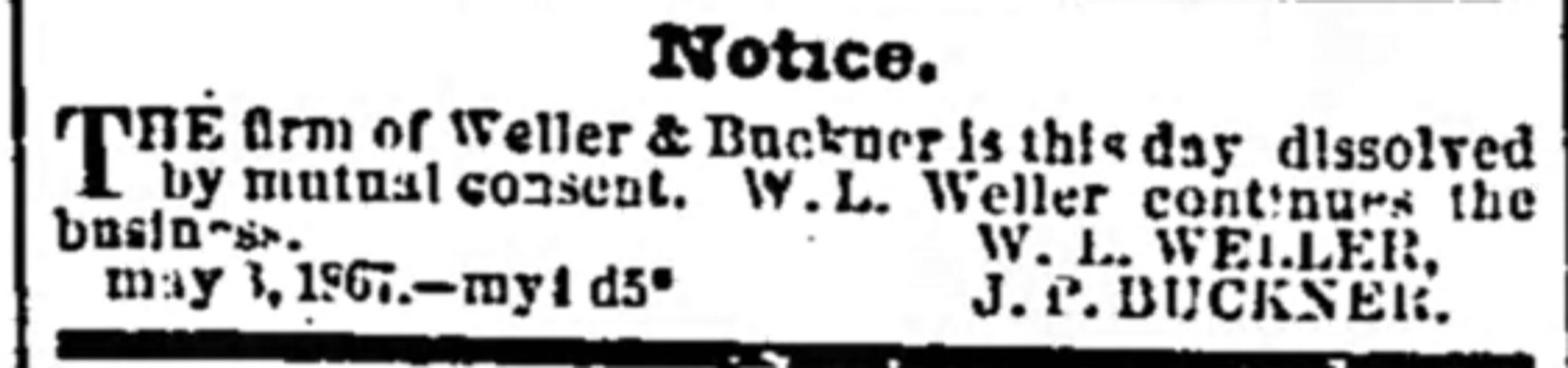

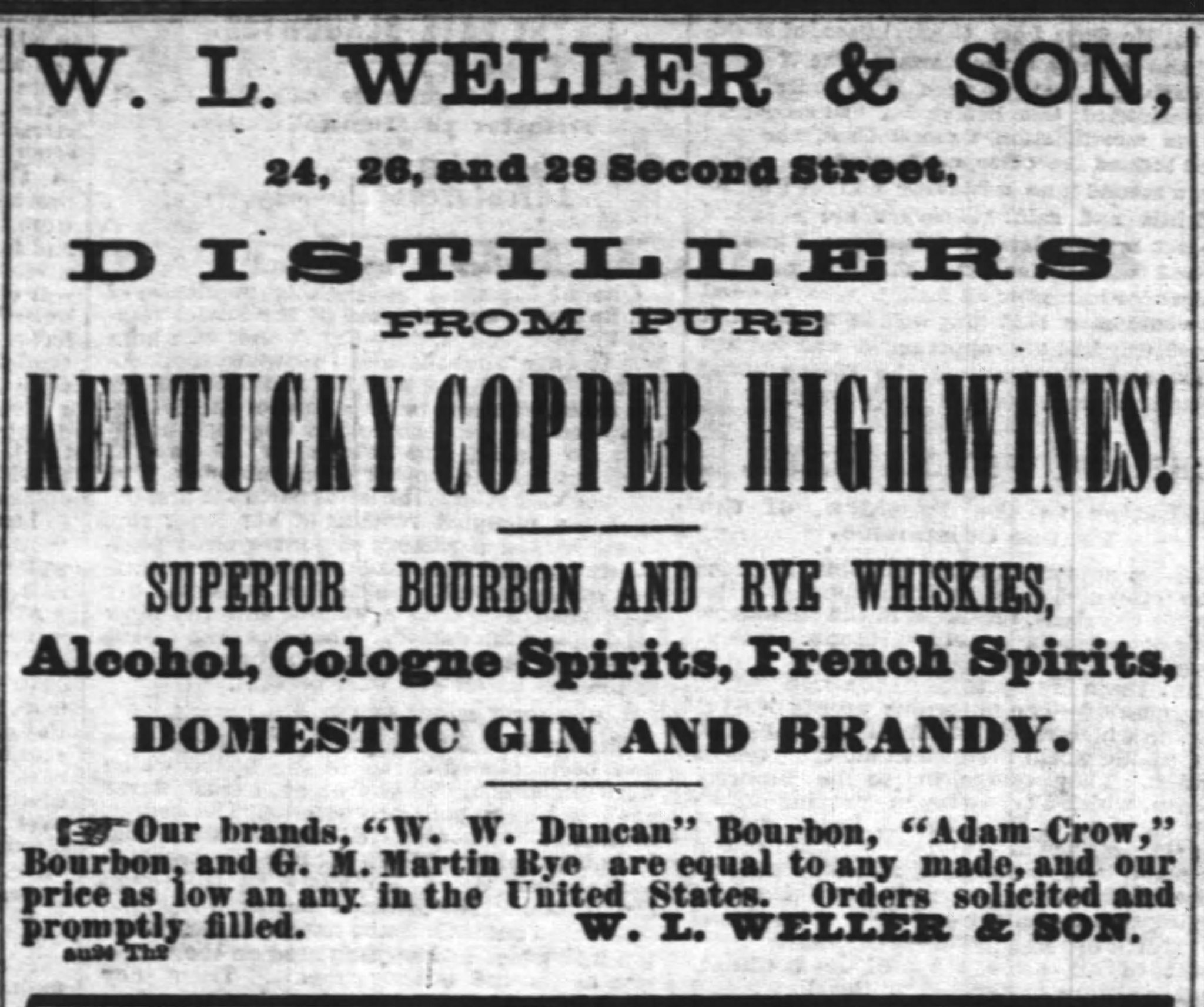

After the war, William partnered with James P. Buckner, though their association was short-lived. Their shop was in a new location- 612 Main Street, across the street from the Louisville Hotel.  William and James parted ways in May 1867. James P. Buckner began to advertise himself at 69 Sixth Street, while W.L. Weller relocated again to 24-28 2nd Street.

William and James parted ways in May 1867. James P. Buckner began to advertise himself at 69 Sixth Street, while W.L. Weller relocated again to 24-28 2nd Street.

By 1870, William eldest son, George, was turning 19 years old and joining the business, so W.L. Weller became W.L. Weller & Son. William Lerue Weller, Jr., George’s younger brother by 5 years, (when he finally came of age) took on politics instead of distilling. He would win the office of Auditor Agent (1900), act as a revenue agent (1903), and perform the duties of County Clerk of the Circuit Court for Louisville and Jefferson County (1902-1907). He also served as Kentucky’s State Senator.

While William and George Weller seemed to be doing well, the company faced bankruptcy in 1878.

Thankfully, the company’s assets were worth more than their liabilities, so they were able to pull through relatively unscathed after selling off a large chunk of whiskey, equipment, and real estate. William’s son and George’s much younger brother, John Charles Weller (now entering his 20s), joined the firm. W.L. Weller & Son became W.L. Weller & Sons.

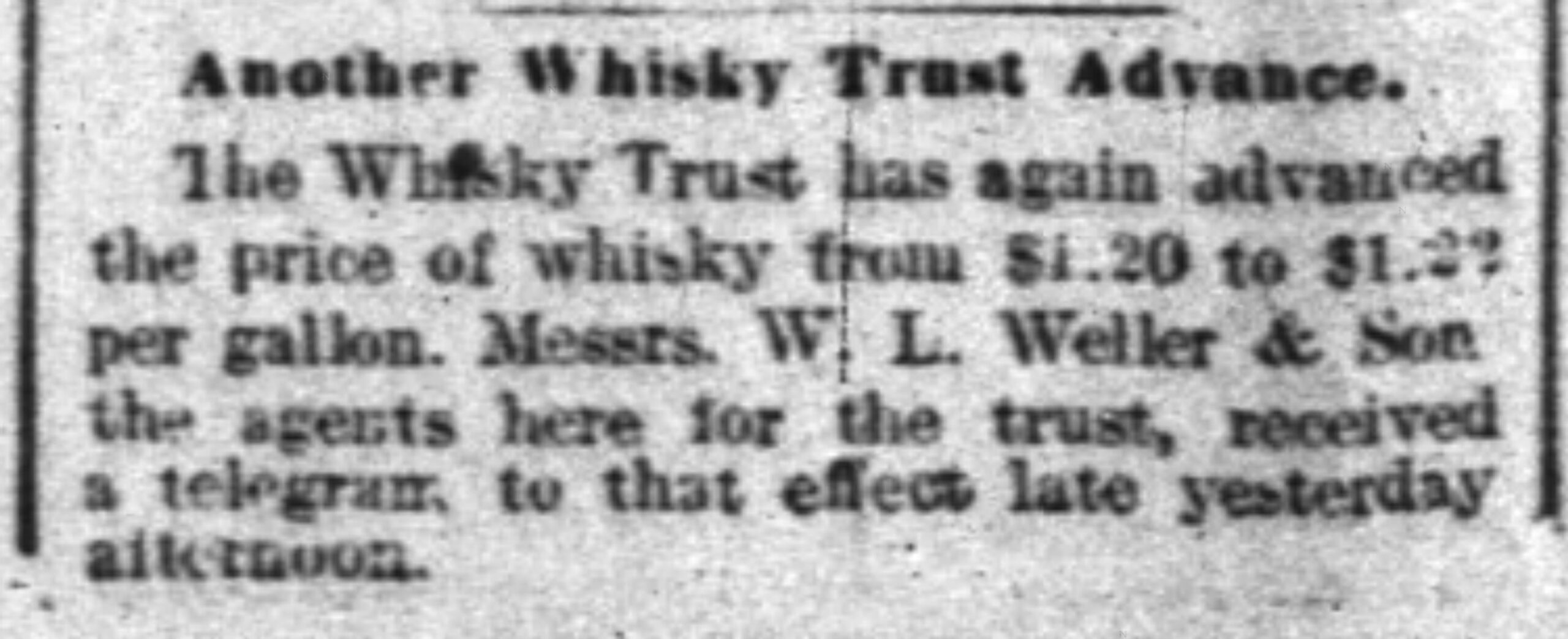

The early 1890s introduced a very lucrative opportunity. W.L. Weller had been given the opportunity to act as agents for the Whiskey Trust in Louisville. This new arrangement put W.L. Weller & Sons into an enviable position. Not only were they privy to all the trust’s plans for price hikes before they happened, they gained access to the trust’s political and financial contacts AND its distribution network! Their address during these good years (1880s & 90s) was at the southeast corner of Brook and Main Streets, just one block east of the famous Galt House on Whiskey Row. (see map below) William L. Weller stepped back from the business in 1896, leaving George P. to take over the role of president.

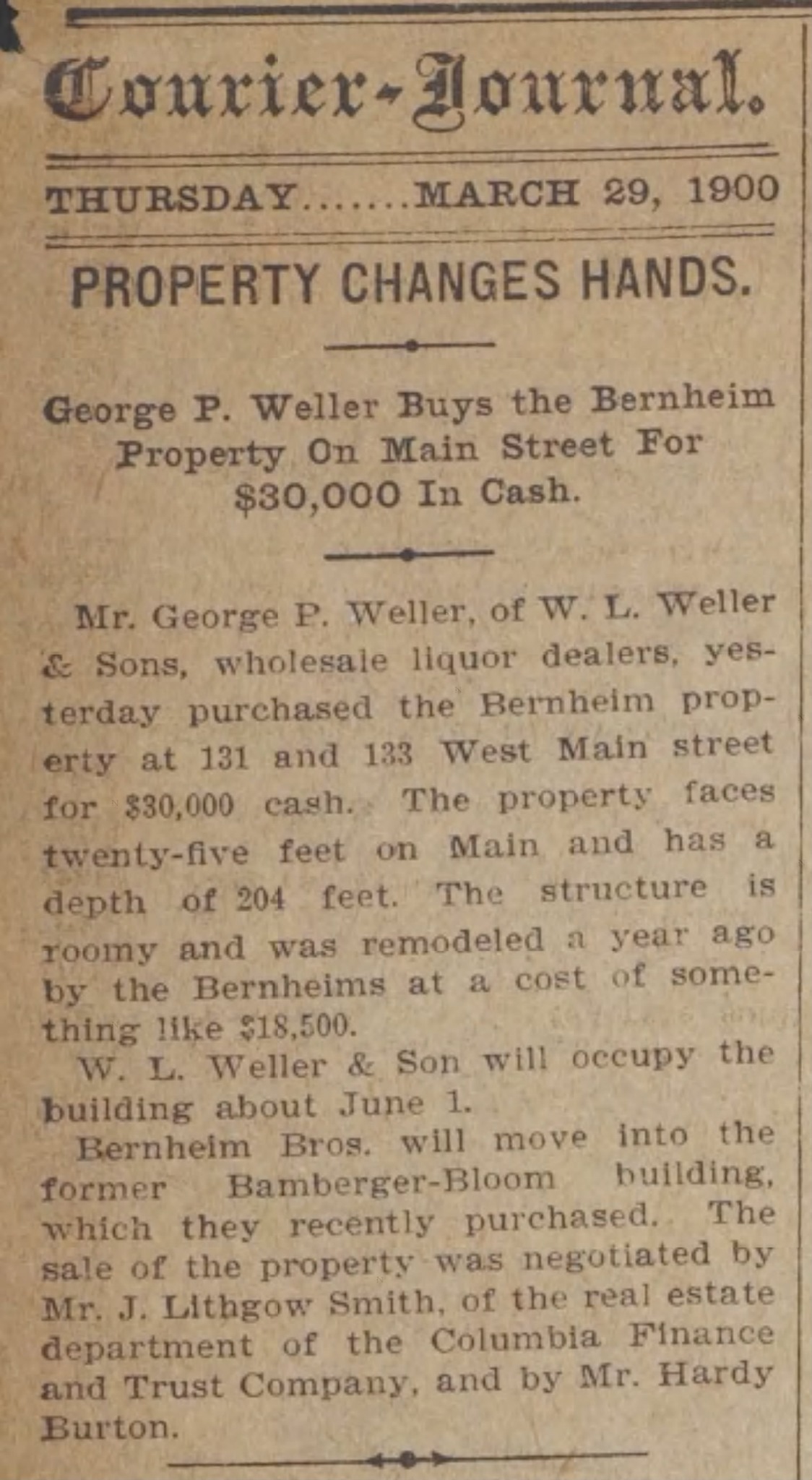

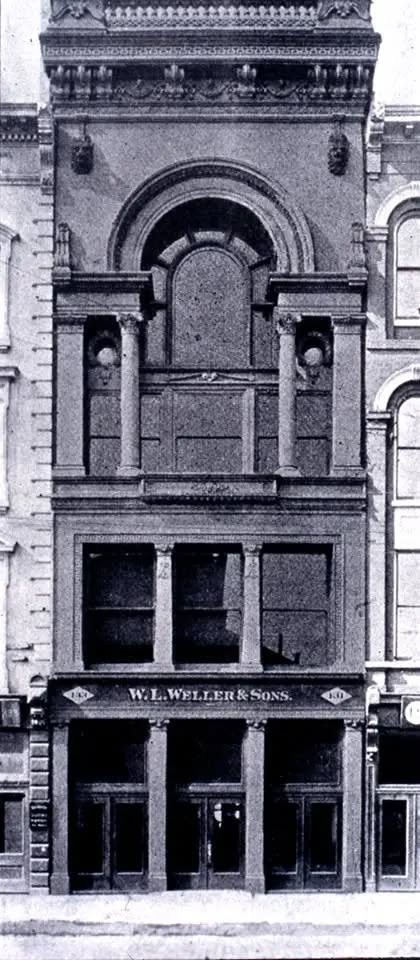

William Lerue Weller died in 1899, bringing an end to his 50 years in the whiskey business. In 1900, George P. Weller bought the Bernheim property at 131-133 West Main Street (Whiskey Row) for $30,000. This is the large, multi-story property normally associated with the Weller firm. (see image below) George’s son, George L. Weller, was admitted as a partner on July 1, 1904. On the same day one year later, John C. Weller withdrew from the firm. John, now 41, was establishing his own wholesale liquor firm, John C. Weller & Co. He, too, would have an address on Whiskey Row and an association with the Whiskey Trust. John’s partner was Gabe J. Felsenthal of Cincinnati. (We’ve discussed G.J. Felsenthal before in association with Lewis Rosenstiel.) John would also become owner of the Burks Springs Distillery in Loretto (the distillery that would one day become Makers Mark). In 1912, John C. Weller & Co. merged with John T. Barbee & Co, adding another distillery to his firm. John would act as president of John T. Barbee & Co., G.J. Felsenthal as secretary/treasurer, and John’s brother-in-law, Gus D. Caldeway, filled the role of vice-president.

William Lerue Weller died in 1899, bringing an end to his 50 years in the whiskey business. In 1900, George P. Weller bought the Bernheim property at 131-133 West Main Street (Whiskey Row) for $30,000. This is the large, multi-story property normally associated with the Weller firm. (see image below) George’s son, George L. Weller, was admitted as a partner on July 1, 1904. On the same day one year later, John C. Weller withdrew from the firm. John, now 41, was establishing his own wholesale liquor firm, John C. Weller & Co. He, too, would have an address on Whiskey Row and an association with the Whiskey Trust. John’s partner was Gabe J. Felsenthal of Cincinnati. (We’ve discussed G.J. Felsenthal before in association with Lewis Rosenstiel.) John would also become owner of the Burks Springs Distillery in Loretto (the distillery that would one day become Makers Mark). In 1912, John C. Weller & Co. merged with John T. Barbee & Co, adding another distillery to his firm. John would act as president of John T. Barbee & Co., G.J. Felsenthal as secretary/treasurer, and John’s brother-in-law, Gus D. Caldeway, filled the role of vice-president.

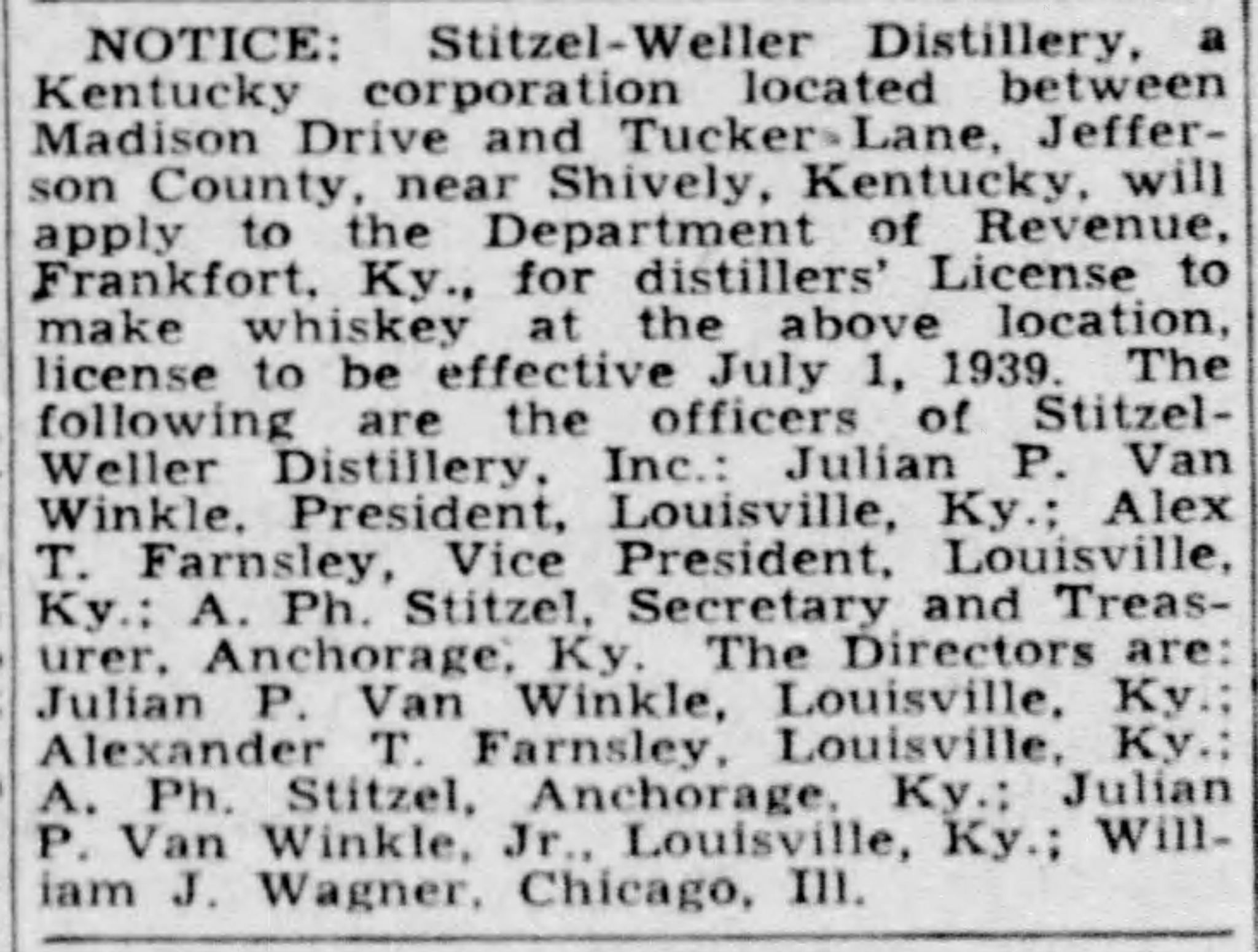

On January 1, 1908, W.L. Weller & Sons filed articles of incorporation with a declared capital of $25,000. The incorporators, each with equal shares, were George P. Weller, George L. Weller, and Alexander Thurman Farnsley. Farnsley, an incredibly well-connected young man (honestly, we’d be here all day with his family’s connections going back to the Mayflower and Plymouth Rock!) had become associated with the company back in 1904. In 1905, he married the daughter of Dr. E.D. Standiford, president of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad- a handy connection for the company, indeed. Now, Farnsley was vice-president of one of the oldest and most respected liquor firms in Louisville. The sky seemed to be the limit for W.L. Weller & Sons.

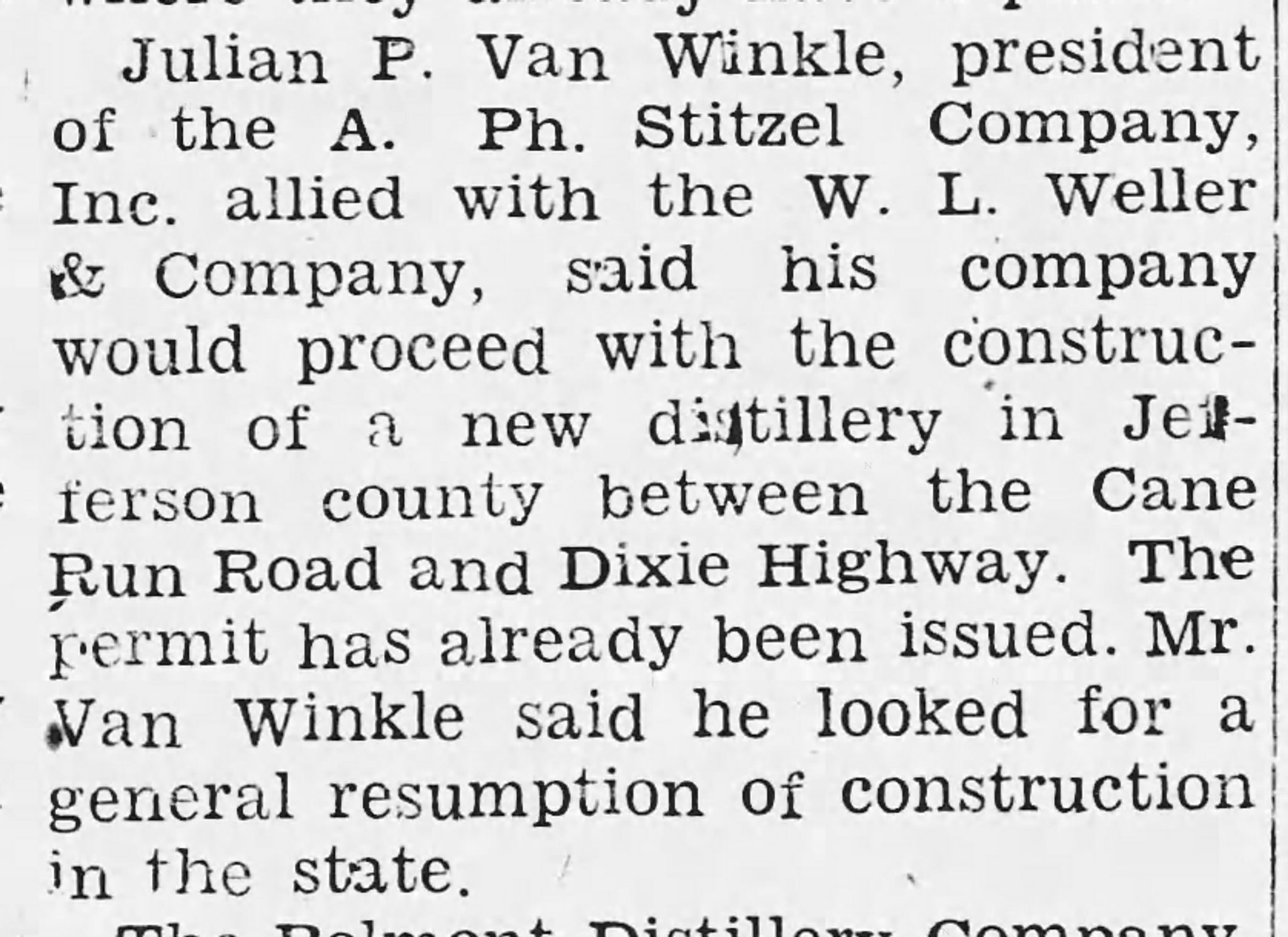

In 1915, amended articles of incorporation were filed for W.L. Weller & Sons, increasing the limit of indebtedness from 50,000 to $150,000. The amendments were signed by Alex T. Farnsley (203 shares of the company) and J.P. Van Winkle (206 shares of the company). Julian and his wife, Katherine, had just welcomed their first son, Julian Procter Van Winkle, Jr. the year before. The new face of Weller & Sons was taking shape before Prohibition set in.

When Prohibition became an inevitability, W.L. Weller & Sons began losing its sons. John C. Weller died in 1918 of pneumonia at the age of 54. He had become vice-president of the American Rubbing Stone Quarry of Indiana before his death. William Lerue Weller, Sr. (politician and son of the founder who died in 1899), died unexpectedly in 1920 of heart disease. George P. Weller, now 68, was living in Anchorage, Kentucky in 1920, and George L. Weller was living in Buffalo, New York where he had taken a position as superintendent at a concrete and steel company. W. L. Weller & Sons had lost its Wellers.

The Stitzel Distilleries- Part 9.

Prohibition.

I started writing about the Stitzel family and the Weller family because I wanted to try to understand how their names came to form one of the most famous distillery related hyphenations to ever exist in the United States. I’ve read many Stitzel-Weller historic accounts. Usually, their histories are lumped together in the same articles, which led me to believe that they had always been associated with one another. So, I was surprised to learn that Stitzels and the Wellers were not connected before Prohibition. I never found any proof that W.L Weller & Sons was sourcing from Stitzel at all or that Stitzel had been using a “wheated recipe” for the bourbons they made after Prohibition. If anything, I found the opposite! What I did find is that Prohibition caused these companies to collide with one another. These two powerful Louisville-based distilling companies faced the chopping block in 1920, but they were preserved through their consolidation. Stitzel Distilling Company, the 18-year-old straight whiskey production site at Story Avenue, and W.L. Weller & Sons, the rectifying liquor firm with 70 years of experience blending and selling whiskey, were merged after Prohibition by the 45-year-old son of Philip Stitzel, Arthur Philip Stitzel, better known as A. Ph. Stitzel.

In March 1917, when Prohibition had become an inevitability, A. Ph. Stitzel’s frustration with the state of the industry was recorded by Louisville’s Courier Journal. He explained that Kentucky’s distilleries were closing their doors and that recent legislation was making it difficult for good men like himself to sell his whiskey to his customers. He would be forced to close his plant on Story Ave, he complained, and sell it for about a tenth of the $350,000 it was worth. In October 1918, Arthur Stitzel purchased his family’s plant and all the equipment that remained within its walls at auction for $25,000. (Before the sale, the property and equipment were assessed as being worth $51,259.) Arthur Stitzel, it seems, had no intention of abandoning the liquor business.

In 1921, Arthur, his wife, Florence, and his cousin, Philip J. Stuetzel, incorporated the A. Ph. Stitzel Company in Louisville with $60,000 capital. Arthur secured the contents of his father’s distillery and formed a corporation to sell the whiskey stored in its warehouses.

Prohibition’s arrival had been anticipated by the men with offices in Cincinnati, Chicago, and New York who owned distilleries and warehouses in Louisville. They had already been stockpiling whiskey barrels for several years by 1920. The men with the biggest stockpiles would control the medicinal whiskey trade, and they all knew it. There was a new game being played by America’s whiskey men, and it was no longer being played by the same rules. Arthur Stitzel was not new to the game, either. He had been 27 years old when the Whiskey Trust bought his grandfather’s distillery at 26th and Broadway, and he watched his father build the family’s new distillery across town at Story Ave and Buchanan. He was 45 when his grandfather’s distillery was bulldozed to the ground and his father’s (now his) distillery was forced to shut down production. He was well-acquainted with the mercurial nature of the whiskey trade, so he was well-equipped to deal with the new normal brought on by Prohibition, and he was willing to employ some questionable tactics to carry his family’s business forward. By 1923, Arthur was able to secure a concentration warehouse permit for his distillery property on Story Ave. It is unclear how he was able to pull off such a feat (one which many that other men were unable to achieve), but he was a very well-connected man in Louisville. His city had already managed to secure a quarter of the available permits in the United States! What was one more for a connected son of Louisville, after all?

It is unclear how closely Louisville’s newly incorporated W.L. Weller & Sons Company was connected to Arthur Philip Stitzel during the early years of Prohibition (at least before 1930), but there was plenty of overlap between the two companies after 1920. George P. Weller and his son, George L., had essentially removed themselves from the whiskey business. W.L. Weller & Sons Co. had been left in the capable hands of Alexander Thurman Farnsley and Julian Procter Van Winkle, Sr. A. T. Farnsley served as president of the company, while J.P. Van Winkle, who had been a salesman for the company since before the turn of the century, served as its vice-president. After the distillery at Story Ave was shuttered in 1920, its warehouses continued to store barrel stocks that belonged to W.L. Weller & Sons. We can see proof of this by looking at auction records from 1923. The auction announcements clearly state that the whiskey to be sold (Mammoth Cave whiskey) was in the “W.L. Weller warehouse” on the premises of Distillery #17 on Story Ave. While it is unclear exactly how the whiskey came to be stored in the Stitzel property’s warehouse, the effort to consolidate the privately-owned whiskey in the newly designated US concentration warehouse helps to illustrate the crossover between the companies. (The same series of auction announcements show similar crossovers with the Ripy Bros. Distillery in Anderson County and the United Distillers Co. of New York City.)

When A. Ph. Stitzel Company was granted its official license to act as a concentration warehouse in 1923, it wasted no time auctioning the sale of its warehouses’ contents. Large amounts of Dowling Bros. whiskey, manufactured at the Cold Water Distillery (RD #148) in Mercer County and previously owned by E. Eppstein & Co., were “sold” (aka repurchased) by A. Ph. Stitzel in July 1923. By November 1923, 7,000 barrels and 500 cases of Mary Dowling’s whiskey from her plants in Lawrenceburg and Tyrone were also scheduled to be transferred into the Stitzel warehouses.

Perhaps now is a good time to remind folks that concentration warehouses are a large source of confusion when it comes to the source of pre-Prohibition brands. The lines between who manufactured whiskeys before Prohibition and who sold most of that whiskey during Prohibition began to blur as early as the 1920s. Newspaper articles often list a concentration warehouse site as being responsible for manufacturing brands when all they were doing was bottling the whiskey that had been stored in their US bonded warehouse. Thankfully, the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 made it necessary to include the name of the original manufacturer on the bottle. In most cases, that information is either revealed on the tax stamp or on the back label- NOT on the front label.

By 1929, A. Ph. Stitzel was named among the distillery owners that had been granted permission to manufacture medicinal whiskey to replenish America’s dwindling stocks. This was not coincidental, as he and his business partners had been lobbying for the opportunity for years. If you recall, Arthur Stitzel bought his father’s distillery in 1918 with all of its equipment intact. With a little investment in refurbishment, the Stitzel Distilling Company on Story Ave was up and running by the second week of December in 1929. A Ph. Stitzel’s distillery produced 40 barrels per day. (The first distillery to fire up was the American Medicinal Spirits Manufacturing Company’s Bernheim Lane plant two weeks prior to the Story Ave plant going online. They were able to produce 165 barrels per day. The following year, the AMSC was also manufacturing about 700,000 gallons of rye whiskey at their plant in Baltimore. The third to begin manufacturing in 1929 was the Glenmore Distillery in Owensboro.)

In February 1930, more crossover between Louisville’s distillery companies was made evident. Miss Blanche Watson, former secretary of George Remus, sold about 2,000 barrels of whiskey that had belonged to her employer to two companies- The Brown Forman Company and the A. Ph. Stitzel Company. ¾ of the whiskey was sold to Brown Forman (approx. 1500 barrels) and ¼ was sold to Stitzel (approx. 500 barrels). The fact that George Remus had been present for the sale of those barrels in Louisville after being released from prison for bootlegging in 1924, killing his wife in 1927, and being acquitted for that crime before selling those barrels for about $210,000 is…well, a bit of a hard pill to swallow. Add to that the fact that Miss Watson then took some of that money from that sale of barrels to a horse track in New Orleans, bet on one of her own horses at 5 to 2 odds, and win…well, let’s just chalk it up to Prohibition being a good time to play fast and loose with money and morals.

When Prohibition drew to a close, the Stitzel plant had doubled its capacity. The amount of two-year-old whiskey in Kentucky’s warehouses should have grown to 7,408,263 gallons, according to the “original gauge” taken after distillation. (The Treasury Department, meanwhile, set that figure at 5,245,088 gallons…so a 30% angel share loss in 2 years? Sounds about right…right?) A. Ph. Stitzel was president of the A. Ph. Stitzel Distillery, Julian Van Winkle had been appointed president of the A. Ph. Stitzel Company, and Alex Farnsley remained president of Weller & Sons. In November 1934, Arthur Philip Stitzel joined with Alexander T. Farnsley and Julian P. Van Winkle to form Waterfill & Frazier, Inc. with a capitalization of $1,000. At the same time, W.P. Weller & Sons decreased its capital stock from $150,000 to $25,000. A new, post-Prohibition plan had been set into action, this time for the newly formed Stitzel-Weller Company. A new warehouse was commissioned to be built by the Comb Lumber Company at the Story Avenue distillery site that would accommodate 15,000 barrels. A new, modern distillery for the company would be built at the intersection of Cane Run and Campground Rds. in Shively, about 10 miles away from the A. Ph. Stitzel distillery site on Story Ave. The new Stitzel-Weller Distillery would open for business on Derby Day in 1935.