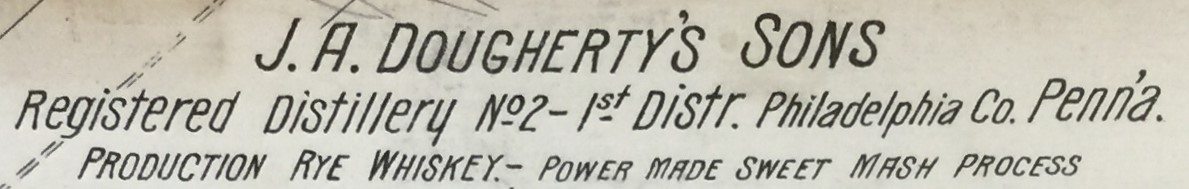

Generally speaking, Bourbon = sour mash and rye whiskey= sweet mash. Historically, I mean- I realize the distinction is all over the board today.

Historic distilling texts reveal that the term “sweet” was used to describe clean vessels and untainted distillate. If the mash entered the worm during a pot still distillation, that unintended accident was said to have “soured the spirit.” If a barrel was cleaned from boiling, scouring and/or burning, it was said to be “sweet.” A dirty barrel or a barrel with imperfections that might taint your mash were considered to be “sour” barrels. I’ve heard a lot of explanations about what the difference between sweet and sour mash is, but I find the easiest explanation is that one production method was clean or “sweet” from the start and one was dirty or “sour” from the start. This is not to say that sour mash is dirty, per se, but the act of adding previously used mash to your clean, new mash, has indeed “soured the mash.” One is not better than the other. It’s just a simple way of creating distinction between methods.

Harrison Hall, in his book ”The Distiller (1818),” describes how different his Pennsylvanian techniques were from the “mode of mashing adopted in Tennessee and Kentucky…” While he recommends against their sour mashing practice (he doesn’t use those words), he also admits to its inexplicable success in getting the job done for those distillers.

“It is not uncommon in some of the distilleries in those states to use dirty casks, into which the requisite quantity of pot ale in a boiling state is thrown, the corn meal is then added, and well stirred; in this state it is suffered to stand there, four or five days, when a small portion of rye and malt is added, and the whole is cooled off. No yeast is added and the stuff is ready for the still in about 4 days more.”

Another important distinction for sweet mashes, at least in Pennsylvania, was that distilleries kept a yeast room on site where they maintained their unique yeast strains. Those yeasts were kept “sweet” through the use of hops. Hop boilers were employed, and small amounts of hops were used to keep any bacterial infections at bay in yeast cultures. While this practice is usually associated with breweries, yeast masters depended on hops in distilleries as well. While it unlikely that the hops contributed to the flavor of pure rye whiskeys made before Prohibition, it can’t be ruled out that that they may have.