Obviously, if the distillers of the Monongahela Valley had the means to grind the grain to make whiskey, they had flour. They had pork and lumber and most natural resources. But there were a few necessities that were very precious to frontiersmen. There was always a need for paper currency and coinage, and settlers needed a means to acquire manufactured European goods, but a major necessity…was salt. Unfortunately, Western Pennsylvania had no local source to fill their need for salt. Whiskey, however, was abundant and provided a great trade good to exchange for barrels of salt. Guess where there was a lot of salt to be traded? Kentucky! (Well, Virginia, really.) Lots of rye whiskey was making its way into the Virginia territory, soon to be known as Kentucky, in the mid to late 1700s. But what made salt so important to frontiersmen?

The North American fur trade had hit its peak at the end of the 18th century and the early 19th century when deer skins dominated the trade. Deer hunters and trappers needed salt to attract the animals, and the west held a wealth in animal skins. Frontiersmen also needed a great deal of salt to act as a preservative for meat and other foods. While there were few sources of salt in Pennsylvania at the time, there was plenty of salt to be had in Kentucky! Pennsylvania supplied the whiskey, and Kentucky supplied the salt- a very fair trade, indeed. We tend to take these necessities for granted today, but salt was no small thing on the frontier. Of course, neither was whiskey!

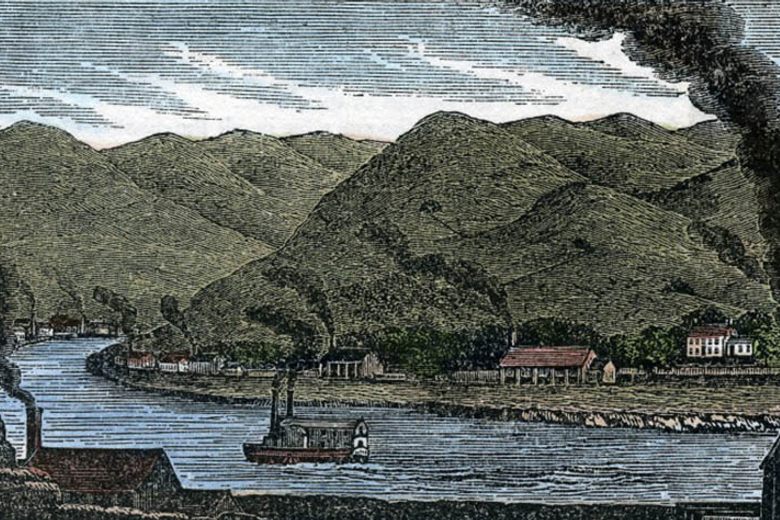

My last post explained that the western part of Pennsylvania did most of its trading with the south via the Ohio River. A major departure point for settlers moving west was Redstone Fort on the Monongahela River. It was a terminus for one of the major migration roads west- originally called Nemocolin’s Trail after the Indian trail it followed. From there, one could board a boat and head north along the Monongahela River (the Monongahela is a rare, northern flowing river) to where it met the Ohio River at Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh), then west and south to the Mississippi. Barges, and their rogue crews loaded with passengers and trade goods, were able to travel downstream from Pittsburgh to New Orleans in anywhere from 40 to 80 days depending on the season and conditions, but the trip back was closer to 4 months. A trip from Kentucky was not nearly as long a journey upstream, but it was no picnic. Shipping businesses were built upon these early efforts and made cities like Cincinnati, Ohio and Louisville, KY great centers of trade. In the very early 1800s, only a couple dozen barges were hauling freight of around 100 tons against the current, but smaller craft were carrying loads of 20 to 40 tons. Flatboats were downstream craft, but keelboats could go back and forth. It’s no wonder that trade in the early 1800s quickly grew to include investments in canals. Trade along the river, even in those early years, was less expensive than the cost of shipping over land. The frontier grew as quickly as the river traffic allowed- and the amount of whiskey being traded grew along with it.