Part One.

Introduction.

Perhaps we should begin where I began- By asking, “Where was Old Grand Dad originally made?” Jim Beam’s website explains the brand’s history this way:

“Known as Old Grand-Dad® to the generations that followed, Basil Hayden Sr. made whiskey the way he wanted. As a farmer-distiller, he went about distilling his whiskey with leftover grain from his crops and perhaps may have preferred rye as a flavoring grain.

Honed over time, his way of crafting whiskey was likely something he handed down to his son; and in turn, to his grandson Colonel R.B. Hayden who would justly name his distillery and bourbon brand after his “Old Grand-Dad”.

First bottled in 1882, very little has changed about it and that’s the only way we’d have it.”

Like most marketing for American whiskey, this description is full of fluff and very loosely based in fact. It’s a tale fit for the back label of a whiskey bottle, but it does hold a kernel of truth. Colonel R.B. Hayden WAS the grandson of Basil Hayden, Sr. And there’s no doubt that the name “Old Grand Dad” was meant to conjure up images of a bygone era for the brand…but why the rye mashbill? And who the heck was R.B. Hayden anyway? I wanted to look into just how much “has changed about it” over the last 133 years.

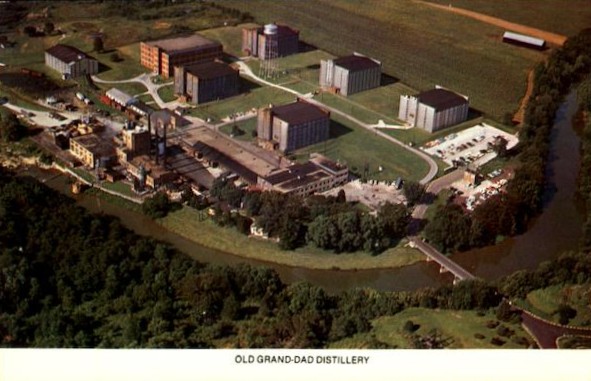

I’ve talked about Old Grand Dad bourbon’s history before during tastings or discussions, but when I thought about it for a moment, I realized I didn’t know much about the brand’s history- other than the lore and stories I’d cobbled together over the years. I couldn’t remember learning anything about where Old Grand Dad had originally been made. I’m aware that TODAY it’s being made by Jim Beam at their Clermont, Kentucky distillery- and HAS been made there since 1987…and I knew that it was made at the Old Grand Dad Distillery in Frankfort, KY before that…but that distillery wasn’t where Old Grand Dad was first made!

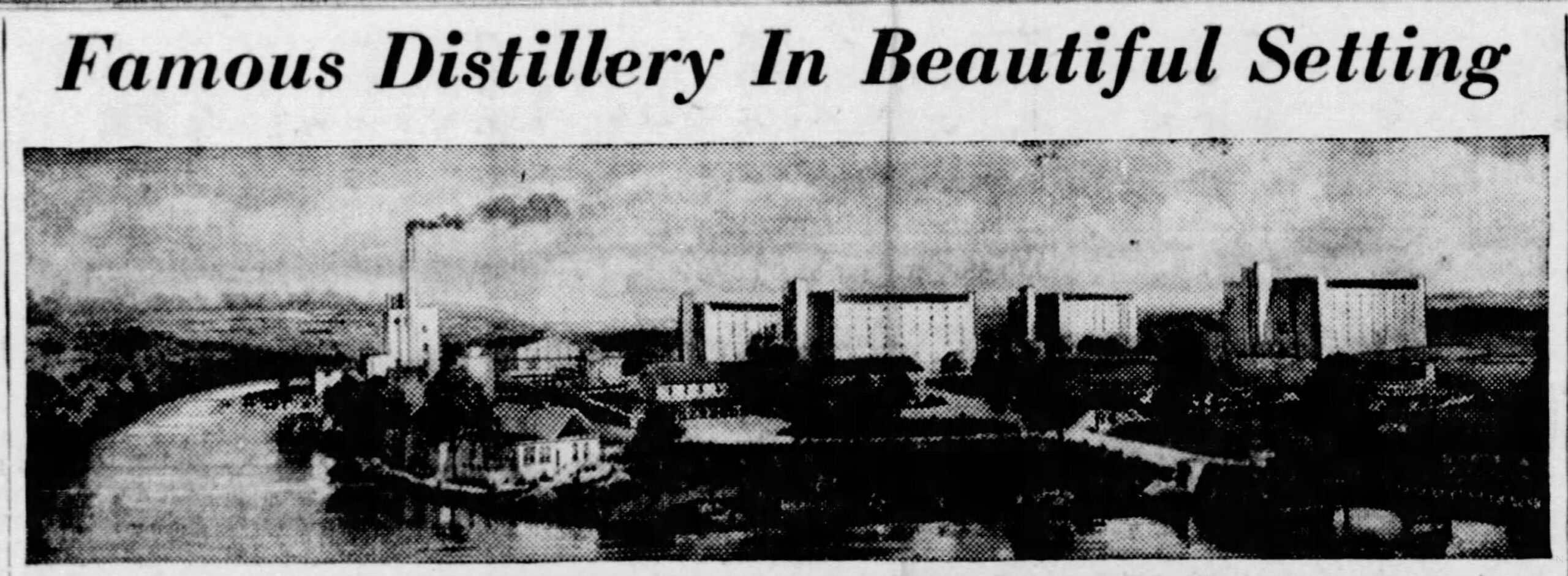

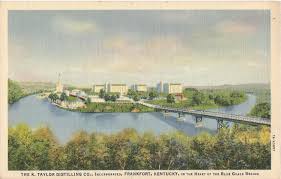

When whiskey history buffs refer to the “Old Grand Dad Distillery”, they’re referring to the old plant on Old Grand Dad Road in Frankfort (Franklin County, KY)- which had originally been the Frankfort Distillery (the one with the swastikas), aka the K. Taylor Distillery after Prohibition. Kenner Taylor was E.H. Taylor, Jr.’s son, and he ran the distillery on the site in Frankfort after Repeal, but OGD wasn’t originally from Frankfort! In fact, Old Grand Dad wasn’t even made at the K.Taylor/Frankfort Distillery until National Distillers acquired the property in 1940 and changed its name to Old Grand Dad Distillery. It’s a confusing back story, for sure, but I suppose when “National Distillers” begins to enter any conversation about historic origins, one must be prepared to dig into some archives for an honest origin story! National Distillers was notorious for shuffling the brands and distilleries they’d acquired over the years. It was never in the company’s interest to explain how little association they actually had with a brand they purchased. It was better (easier?) to just talk up the history and tradition of their brands and pretend it was theirs all along! Needless to say, all bets for historic accuracy are off when National Distillers gets involved.

When whiskey history buffs refer to the “Old Grand Dad Distillery”, they’re referring to the old plant on Old Grand Dad Road in Frankfort (Franklin County, KY)- which had originally been the Frankfort Distillery (the one with the swastikas), aka the K. Taylor Distillery after Prohibition. Kenner Taylor was E.H. Taylor, Jr.’s son, and he ran the distillery on the site in Frankfort after Repeal, but OGD wasn’t originally from Frankfort! In fact, Old Grand Dad wasn’t even made at the K.Taylor/Frankfort Distillery until National Distillers acquired the property in 1940 and changed its name to Old Grand Dad Distillery. It’s a confusing back story, for sure, but I suppose when “National Distillers” begins to enter any conversation about historic origins, one must be prepared to dig into some archives for an honest origin story! National Distillers was notorious for shuffling the brands and distilleries they’d acquired over the years. It was never in the company’s interest to explain how little association they actually had with a brand they purchased. It was better (easier?) to just talk up the history and tradition of their brands and pretend it was theirs all along! Needless to say, all bets for historic accuracy are off when National Distillers gets involved.

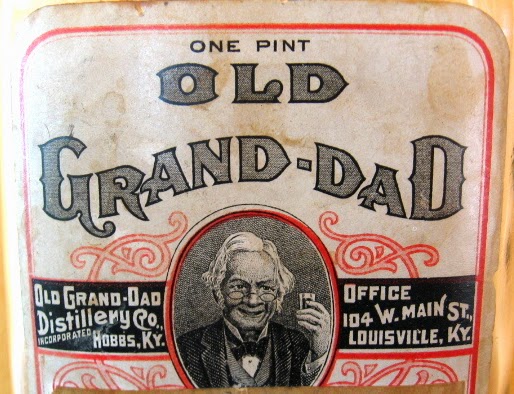

That being said, “Old Grand Dad” was a legacy brand that earned its reputation for excellence long before Prohibition. During Prohibition, the American Medicinal Spirits Company (which would later become National Distillers) owned the name “Old Grand Dad”- and all the patents and brand recognition that came with that ownership. The AMSC could use that beautiful orange label to repackage any number of whiskeys from any number of their concentration warehouses during Prohibition. Most collectors of antique whiskeys can tell you that their Prohibition-era pints of “Old Grand Dad” are repackaged whiskeys from one of the Wathen family’s distilleries. (You can clearly see the Wathen name on back labels and tax strips.) Richard E. Wathen was the president of the American Medicinal Spirits Company after 1927, so the Wathens’ stockpiles of whiskey were conveniently used to fill bottles labeled “Old Grand Dad”. Those same collectors of antique whiskeys will also tell you how wonderful those pre-Pro pints of OGD taste- but it’s worth noting that the whiskey in those pints was manufactured in a distillery that was already rubble by the 1930s. The famous distillery responsible for manufacturing that whiskey for the Wathens before Prohibition, also known as the Old Grand Dad Distillery, was about 12 miles north of Bardstown, not in Frankfort.

The Wathen family wasn’t solely responsible for the reputation of Old Grand Dad BEFORE Prohibition. They simply assumed ownership of a famous distillery in 1899 which made a famous brand of whiskey. The Old Grand Dad brand was already about 17 years old by 1899 and had already earned its reputation in the industry. (For a modern perspective, consider the fact that a majority of America’s most famous craft distillery brands are less than 15 years old, so 17 years was plenty of time to build a reputation!) Of course, the Wathens didn’t hurt Old Grand Dad’s reputation either, folks!

The Wathens came to be involved with the “Old Grand Dad” brand in 1899. This was also the year that nearly 90% of Kentucky’s distilleries were absorbed into the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company, a newly-formed subsidiary of the Whiskey Trust. (Read more on this topic HERE.)

The Wathens came to be involved with the “Old Grand Dad” brand in 1899. This was also the year that nearly 90% of Kentucky’s distilleries were absorbed into the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company, a newly-formed subsidiary of the Whiskey Trust. (Read more on this topic HERE.)

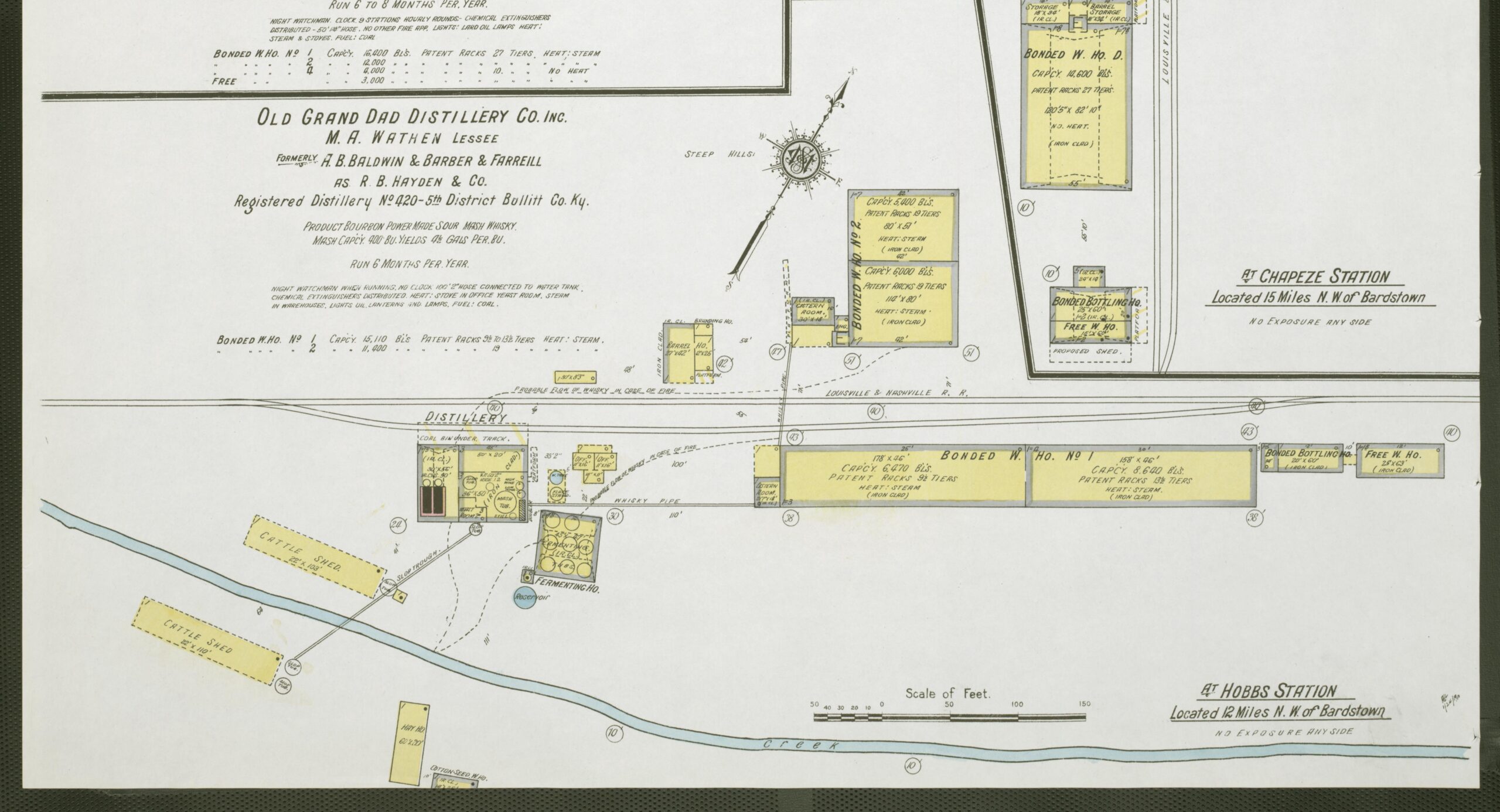

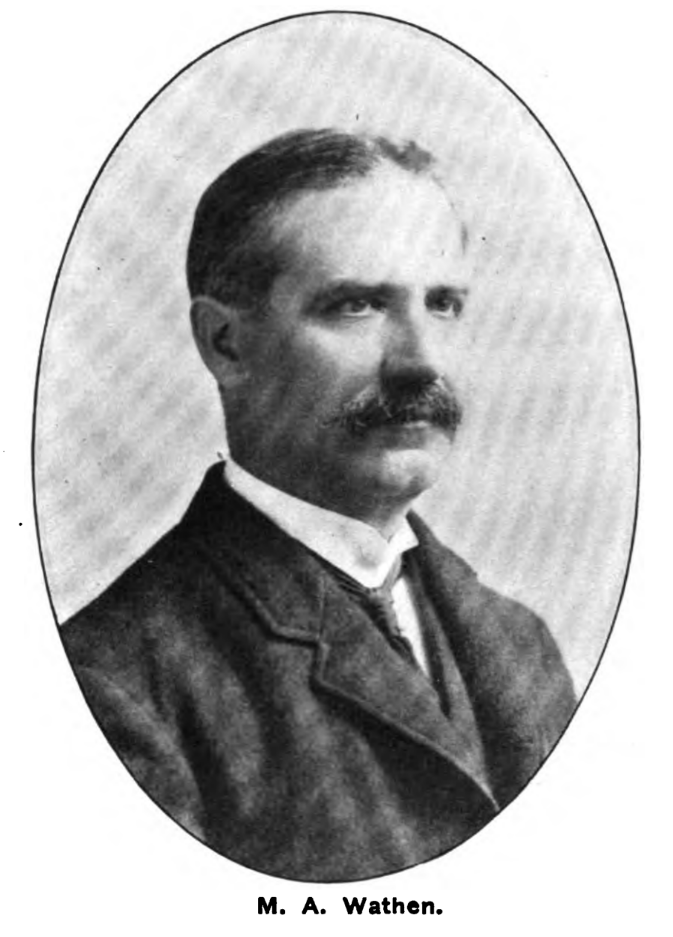

Raymond B. Hayden’s Distillery at Hobb’s Station in Bulleit County was renamed “The Old Grand Dad Distillery” after its most famous brand by the distillery’s new lessee, Martin Athanasius (M.A. or “Nace”) Wathen. (If you’re wondering which Wathen that was, “Nace” was J.B. (John Bernard) Wathen’s brother and R.E. (Richard Eugene) Wathen’s uncle…and beneficiary of the role that his family would play within the New Whiskey Trust.)

Did you get all that? Before Old Grand Dad whiskey was made at Jim Beam’s distillery in Claremont (Bulleit County), it was made in Frankfort (Franklin County), and before that it was made in Hobbs Station (Bulleit County)! Suffice it to say, the brand has hopscotched around a bit…and the whiskey changed as it went. But was the R.B.Hayden Distillery-turned-OGD Distillery at Hobbs Station the real birthplace of the whiskey behind the Old Grand Dad brand? And where the heck is Hobbs Station? If the brand was created by Raymond B. Hayden, grandson of Basil Hayden, Sr., shouldn’t the OGD distillery have been in Marion or Nelson County? We’ll answer some of these questions in my next post.

Old Grand Dad. Part 2.

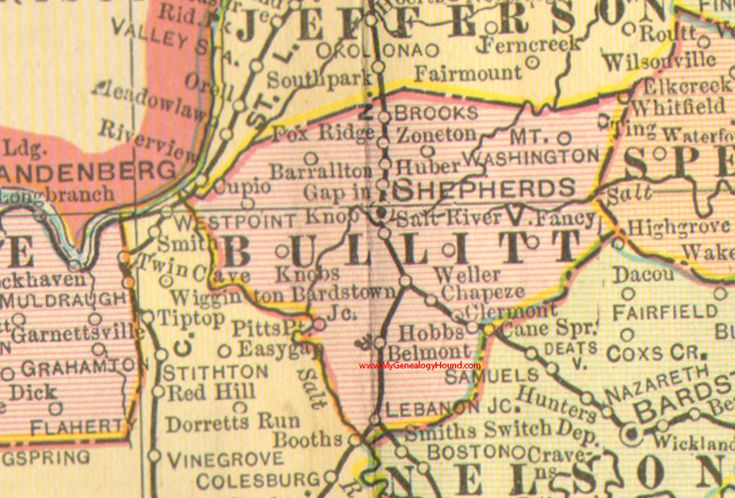

Hobbs Station

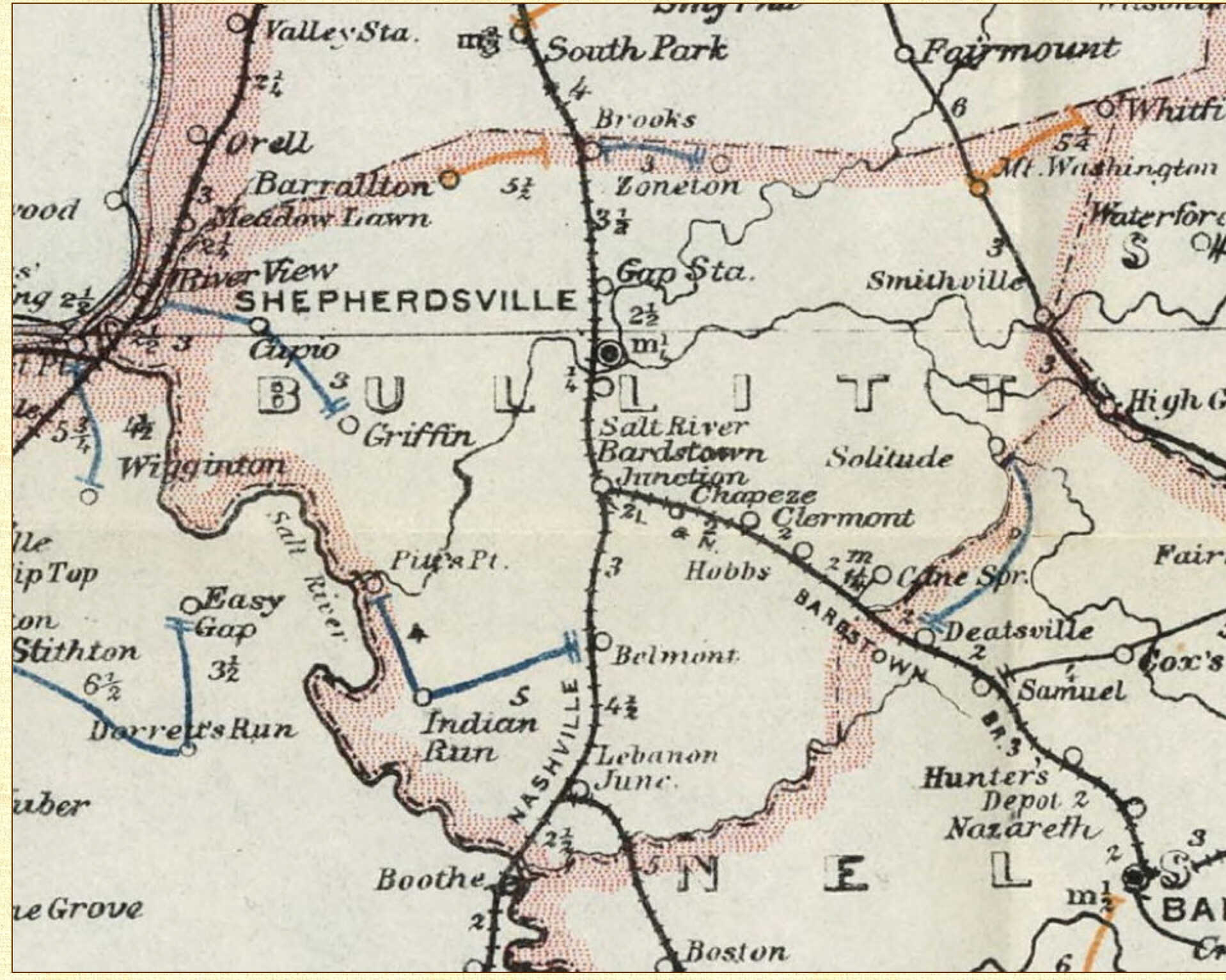

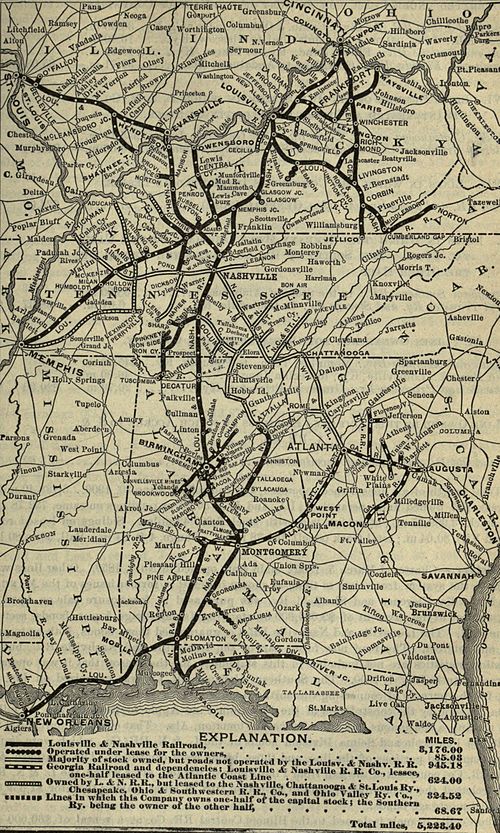

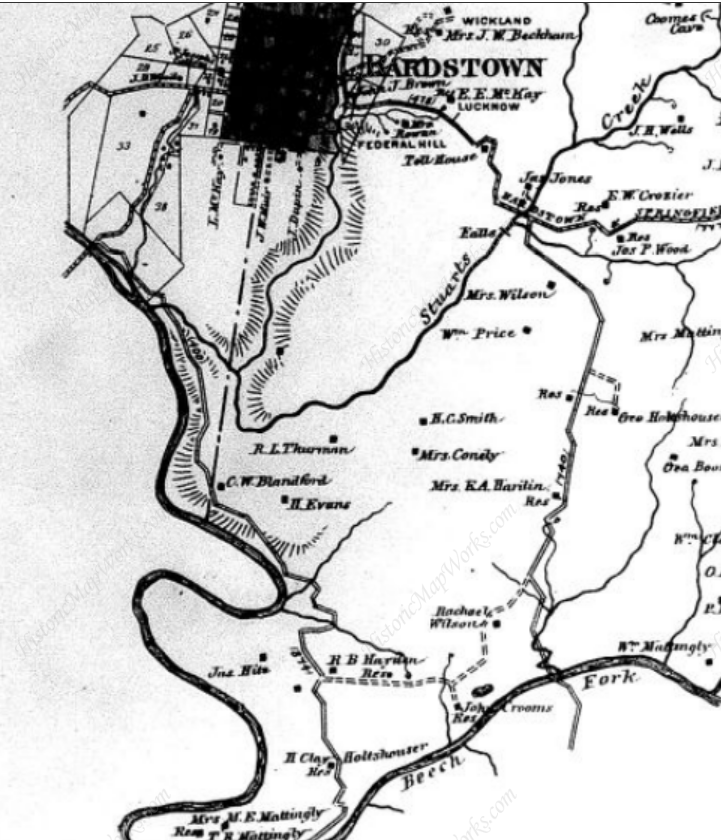

Yesterday, I asked, “Where the heck is Hobbs Station?” Well, as the name makes clear, it was a railroad station, and that station was about 12 miles northwest of Bardstown, Kentucky. The Bardstown Branch was a spur of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad which diverged from the main line (to Nashville) at Bardstown Junction, several miles south of Shepherdsville. The stops along the branch (bound southeast from Bardstown Junction) were as follows:

1. Chapeze

2. Clermont (today, home of Jim Beam Distillery)

3. Hobbs

4. Cane Springs

5. Deatsville

6. Samuels

7. Hunters Depot

8. Nazareth

9. Bardstown.

From Bardstown, the spur’s tracks continued southeast to Springfield. As you can see on the map, Hobbs Station is clearly within Bulleit County and was a stop on the way to Bardstown. Once the distillery at Hobbs Station was demolished, the need for a station disappeared, so it no longer appears on maps or in Google searches. But WHEN was it demolished? And why would the American Spirits Manufacturing Company demolish such an iconic location?

From Bardstown, the spur’s tracks continued southeast to Springfield. As you can see on the map, Hobbs Station is clearly within Bulleit County and was a stop on the way to Bardstown. Once the distillery at Hobbs Station was demolished, the need for a station disappeared, so it no longer appears on maps or in Google searches. But WHEN was it demolished? And why would the American Spirits Manufacturing Company demolish such an iconic location?

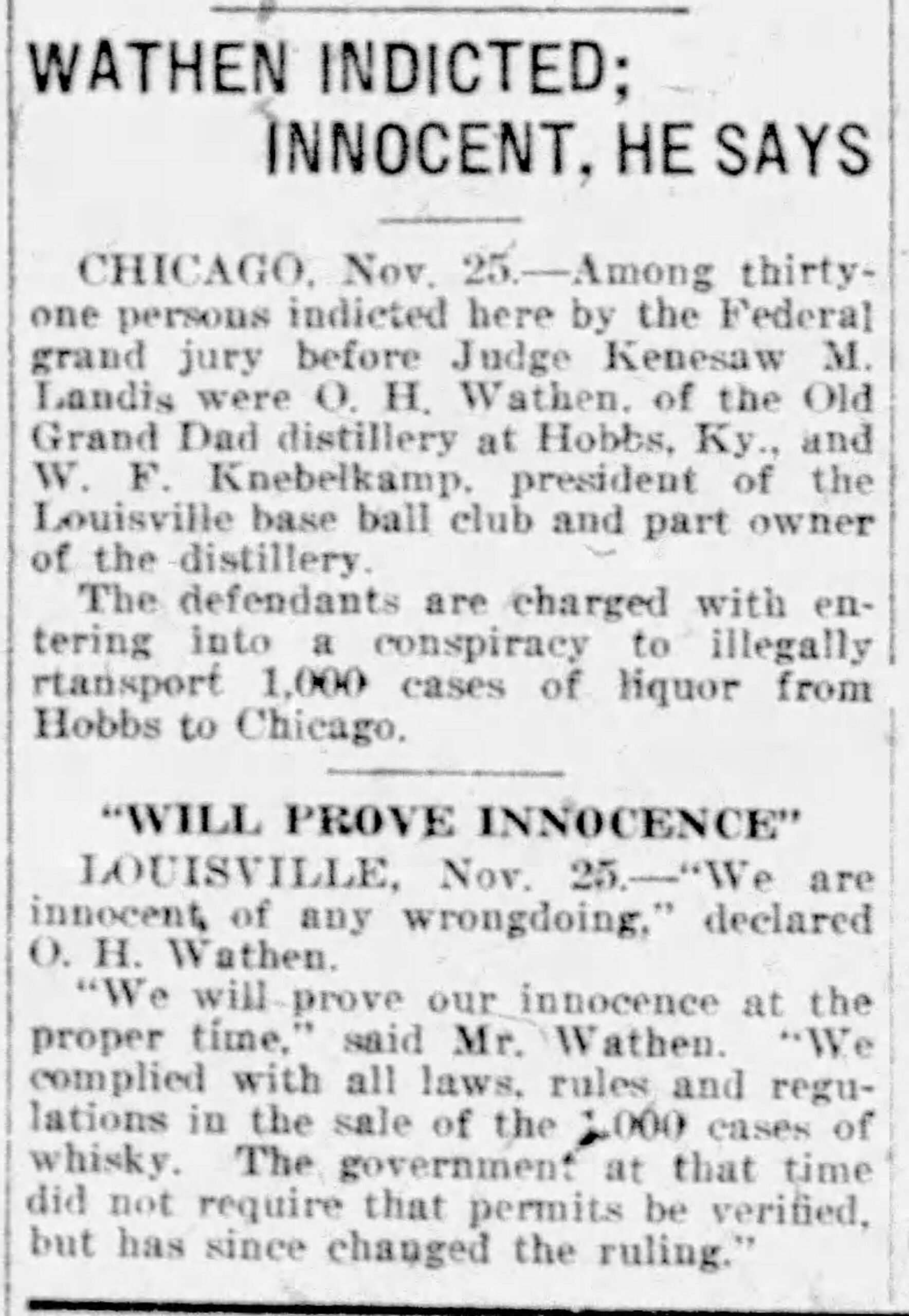

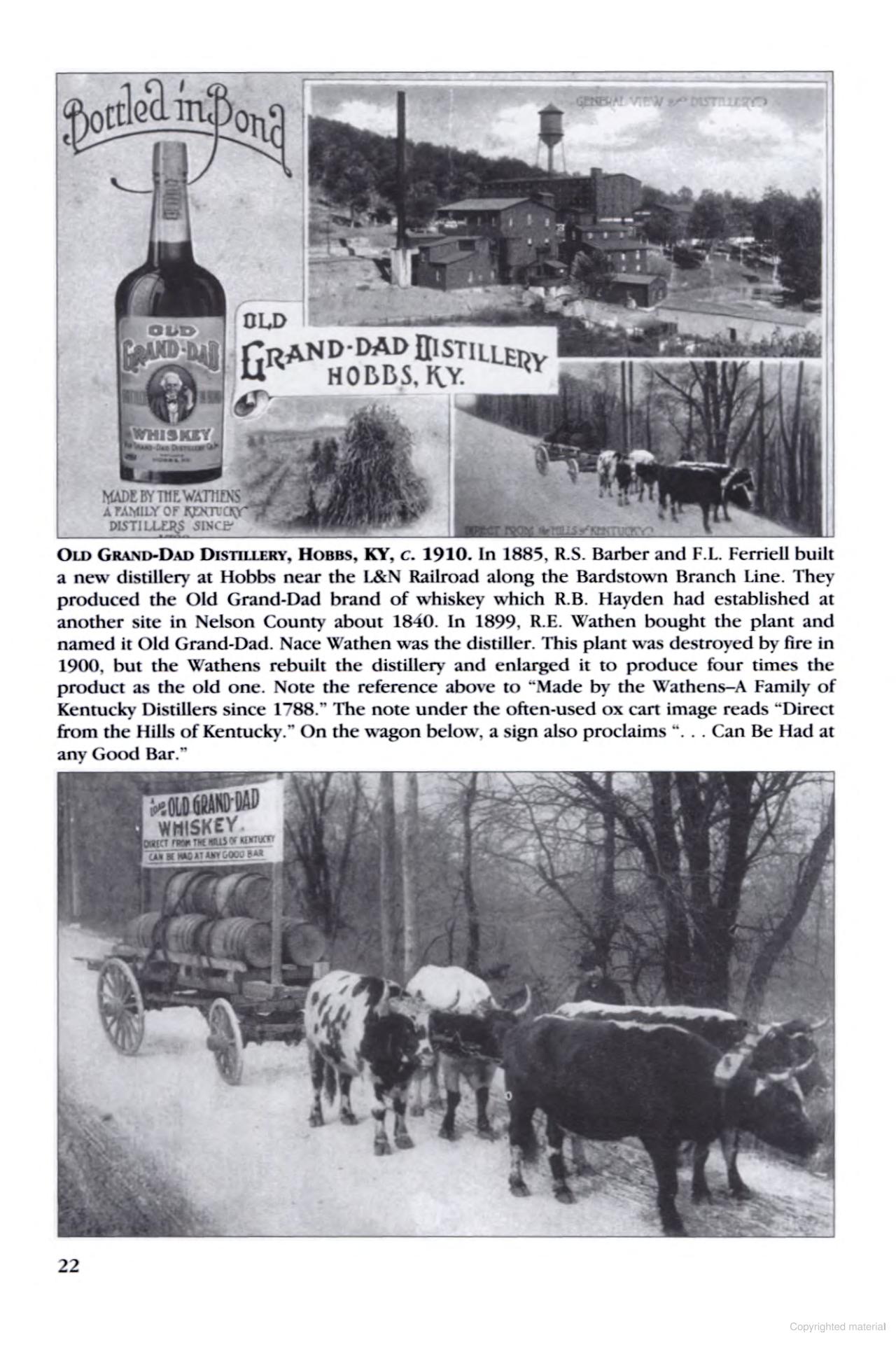

Thankfully, there is an account describing the sad state of the R.B.Hayden-turned-Old Grand-Dad distillery at Hobbs Station. The description makes it clear that the site had already fallen into ruin by 1926, which would have rendered the distillery inoperable and, therefore, of little importance to its owner, the American Spirits Manufacturing Company. In 1927, the American Spirits Manufacturing Company reorganized itself as the American Medicinal Spirits Company and had already begun to prepare their intact, operable distillery sites in anticipation of the medicinal whiskey production permits they had been lobbying to obtain. Unfortunately for the Old Grand Dad Distillery at Hobbs Station, it was not on that list of sanctioned sites, so it was abandoned and left to rot in the wake of scandal, burglaries, and corporate reorganization. (Read about the 1920 scandal involving the illegal transport of Old Grand Dad whiskey out of the Hobbs Station distillery’s location and the indictments that followed in articles below.) The “Bulletin of Pharmacy” published this account in December 1926, which was written by the editor of “The Kentucky Druggist”:

“A few weeks ago the doctor advised a trip to the country, away from the activity of the city, and, receiving an invitation from a friend living in Bullitt county, who has a home out among the high hills, with nothing but wilderness and forest trees surrounding, the editor arranged to take the 9:10 A.M. train of the L. & N. for Hobbs Station, Ky. Not knowing anything about the surroundings of the place he was headed for, he left contented, Soon the flagman began to go through the train calling out the names of the different stations. He said, “Next stop is Chapeze” ; then later he cried out, “Next stop Clermont”; and finally the conductor came along, looked at the editor, smiled, and then was joined by the flagman, and said, “The next stop is Hobbs Station. ” They evidently surmised that it was the editor’s first trip to Hobbs, or the ” Wilderness,” as they may have called it. They remained on the platform while the editor began to alight just to see the expression on his face. The editor saw the humor of the situation and asked the conductor the name of the best hotel there. By this time the engineer caught the situation, smiled, gave a few extra toots of his engine whistle, and waved farewell. The editor glanced about him and witnessed one of the saddest and most deplorable of surroundings-a sight that would have made men of younger age weep. There before him were the beautiful, high hills of Bullitt county covered with thousands of forest trees, a beautiful sight. But, alas, at his feet was a different reminder! There was no railroad station, but instead there was the dismantled ruins of the famous old Grand Dad Distillery -nothing showing above the ground but the stone foundation of what at one time was the producing place of more hilarity than almost any other spot in the world. All that remained were the old decayed mash tubs, the old boiler long in discard, the extinct warehouse and bottling plant, and the copper stills that could only be sold for junk. It was indeed a sad sight, and brought back memories of the days taken away from us, namely, the good old days of personal liberty-the time when liberty had a meaning to American citizens. The only thing that seemed to have life was the cold water that was emerging from the bottom of a 500- foot hill. After pondering over the sad scenes for a few moments, the host arrived with his Studebaker, and…”

(written by Bob Frick, Editor The Kentucky Druggist)

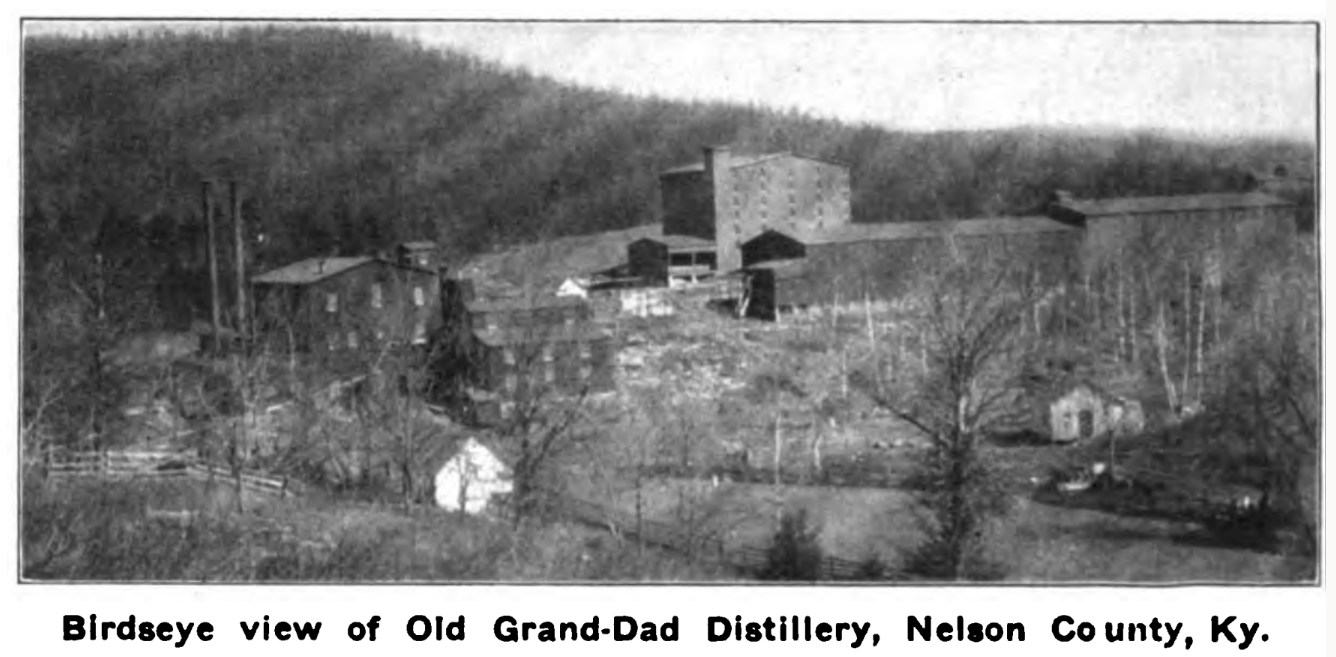

The late Dixie Hibbs (Rest in Peace, Mrs. Hibbs. You will be missed.) published some wonderful images of the old distillery at Hobbs Station in her book, “Central Kentucky: Bulleit, Marion, Nelson, Spencer and Washington Counties.” The images show the distillery in its heyday before Prohibition, circa 1910. Posterity has not preserved the memory of the old site because the “Old Grand Dad” name was swiftly reduced from a brick-and-mortar distillery site with an historic brand of whiskey to a name on a letterhead. The American Medicinal Spirits Company formed the “Old Grand Dad Distilling Company” as a subsidiary in October 1929, along with 16 other major brand-name-turned-distilling-company names. (Read more about that HERE.)

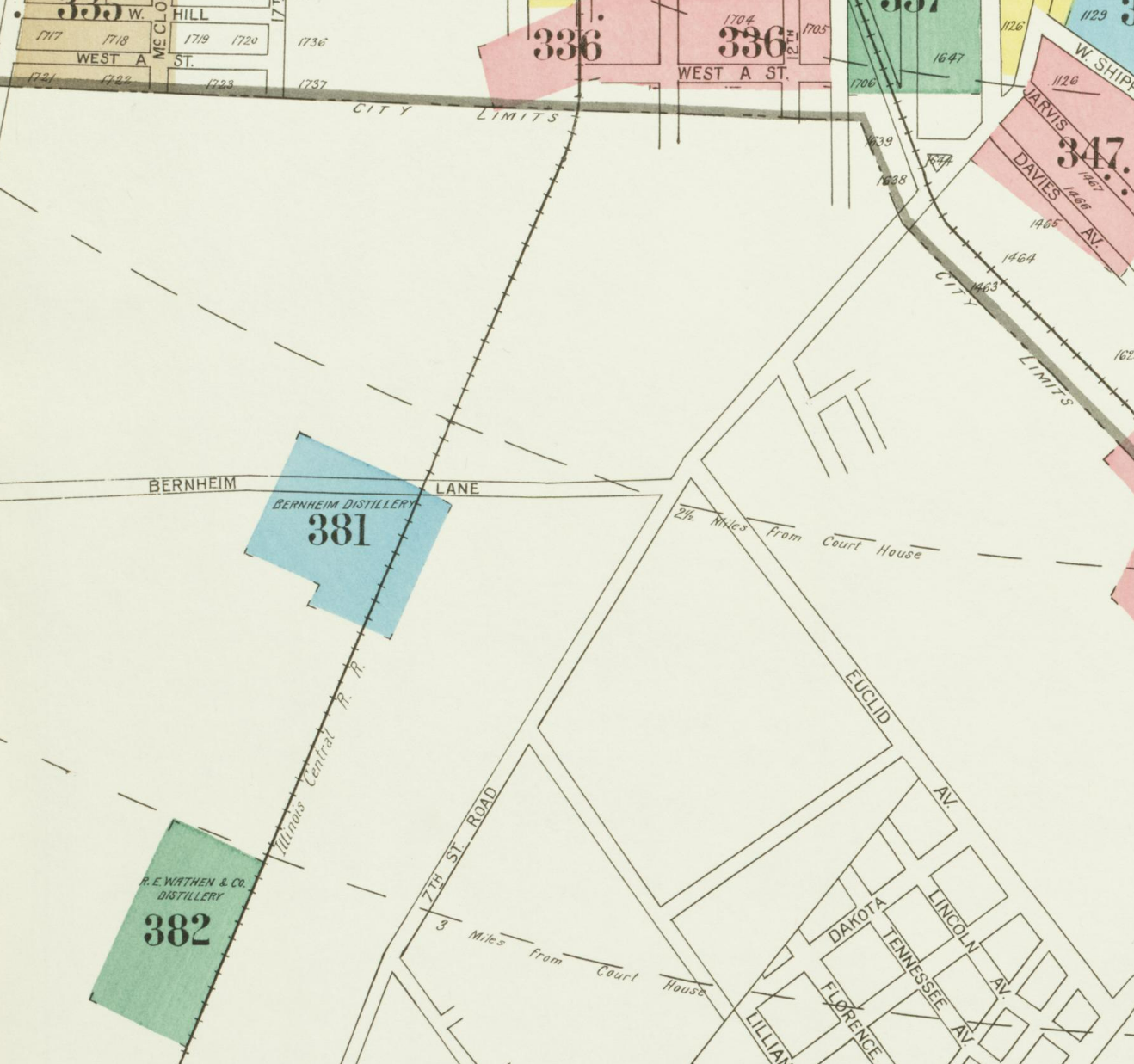

Old Grand Dad Distilling Company did not represent an ACTUAL distillery anymore. It existed in name only and presented itself on labels of whiskey bottled by the Wathen family. As we discussed yesterday, the “Old Grand Dad” brand of whiskey was homeless for almost 20 years between the time it was manufactured at Hobbs Station and the time it found a new home in Frankfort. It wasn’t until 1940 that National Distillers (AMSC 2.0) renamed the K. Taylor Distillery, aka the Frankfort Distillery, as the Old Grand Dad Distillery. Pint bottles of Old Grand Dad from the Prohibition era were filled with whiskey being stored in concentration warehouses belonging to the Wathen family. Auction listings clearly show that whiskey once stored at the Hobbs Distillery location had been relocated to R.E. Wathen’s concentration warehouse No.18 in Louisville, Jefferson County. (R.E.Wathen’s Distillery location, R.D. #19, was below the old Bernheim distillery, across the street from where the Michter Distillery’s in Shively sits today. See map in Part 3.) Thank goodness the Bottled-in-Bond Act, which made it necessary to record where the whiskey in each bottle had originally been made!

Old Grand Dad. Part 3.

The Wathens.

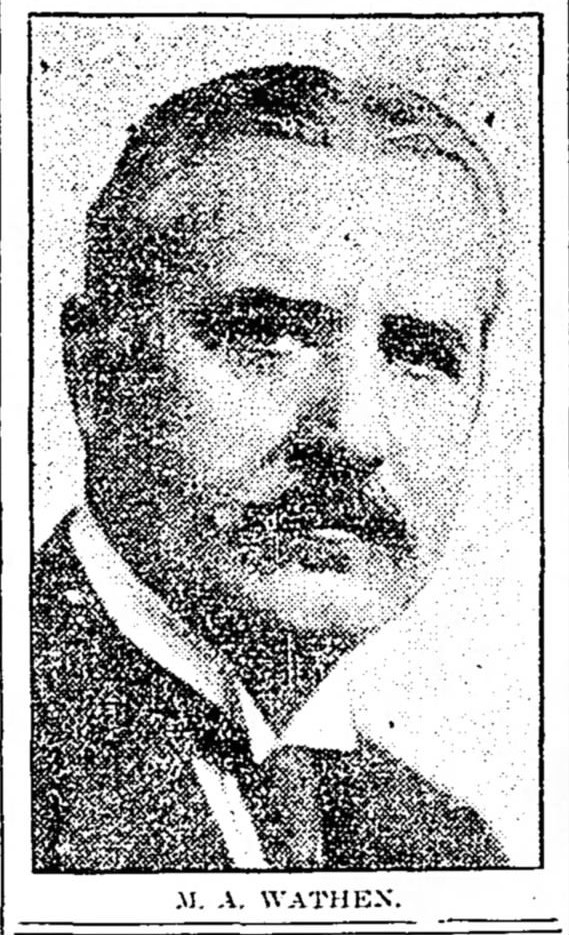

So, we’ve discussed how the R.B. Hayden Distillery at Hobbs Station was officially re-named the “Old Grand Dad Distillery” in 1899 by M.A. Wathen. But who was M.A Wathen, and how did he come to own it? Let’s look at how M.A. fits into the Wathen family and how Old Grand Dad managed to survive into the 20th century.

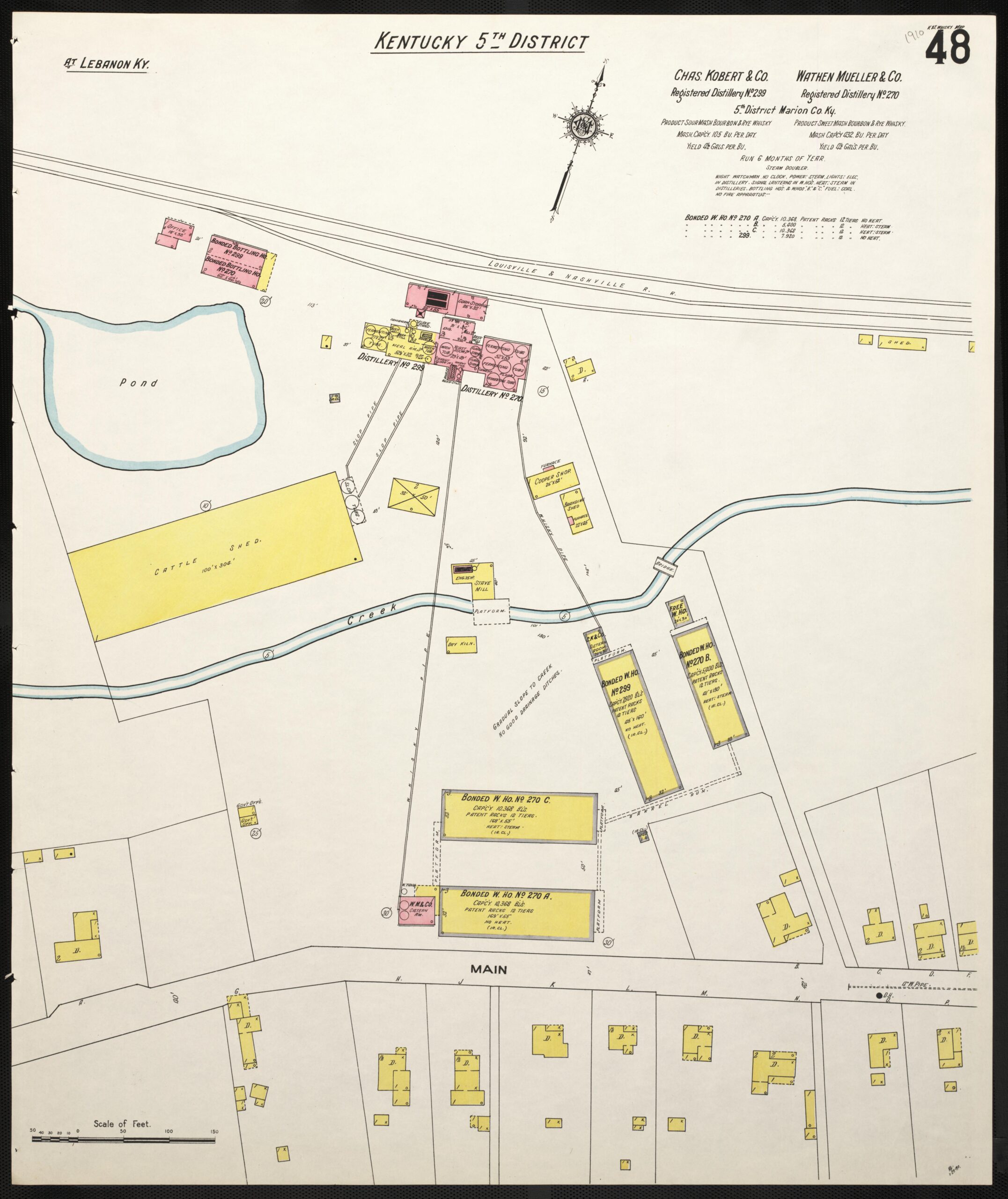

Martin Athanatius “Nace” Wathen (M.A.) was the son of Richard Bernard (R.B.) Wathen and grandson to the patriarch of Wathen distillers in Kentucky, Henry Hudson Wathen. Born in 1857, he was the 10th of 11 children. Nace (M.A) was about 24 years old in 1881 when he went to work for his older brothers. John Bernard, aka J.B. Wathen, Sr., (the eldest of R.B. Wathen’s sons), and Richard Nicholas, aka R.N. Wathen or “Nick”, brought Martin on as bookkeeper for the J.B. Wathen & Bro. Company. Of course, by the time “Nace” joined the company, his older brothers had already begun to broaden the scope of their distilling business. In 1879, they forged a partnership with H. Mueller and Charles Kobert of Cincinnati and enlarged their original plant in Lebanon to include a second still house- the new facility produced sour mash whiskey, while the original continued to manufacture sweet mash whiskey! (Yes, that’s right- Sweet and sour mash techniques were unique processes, enough to require separate facilities!) The original plant had become the Wathen, Mueller & Co. Distillery (aka the Rolling Fork Distillery- RD #270) and its partner the Kobart Distillery (aka the Cumberland Distillery- RD #299).

Martin Athanatius “Nace” Wathen (M.A.) was the son of Richard Bernard (R.B.) Wathen and grandson to the patriarch of Wathen distillers in Kentucky, Henry Hudson Wathen. Born in 1857, he was the 10th of 11 children. Nace (M.A) was about 24 years old in 1881 when he went to work for his older brothers. John Bernard, aka J.B. Wathen, Sr., (the eldest of R.B. Wathen’s sons), and Richard Nicholas, aka R.N. Wathen or “Nick”, brought Martin on as bookkeeper for the J.B. Wathen & Bro. Company. Of course, by the time “Nace” joined the company, his older brothers had already begun to broaden the scope of their distilling business. In 1879, they forged a partnership with H. Mueller and Charles Kobert of Cincinnati and enlarged their original plant in Lebanon to include a second still house- the new facility produced sour mash whiskey, while the original continued to manufacture sweet mash whiskey! (Yes, that’s right- Sweet and sour mash techniques were unique processes, enough to require separate facilities!) The original plant had become the Wathen, Mueller & Co. Distillery (aka the Rolling Fork Distillery- RD #270) and its partner the Kobart Distillery (aka the Cumberland Distillery- RD #299).

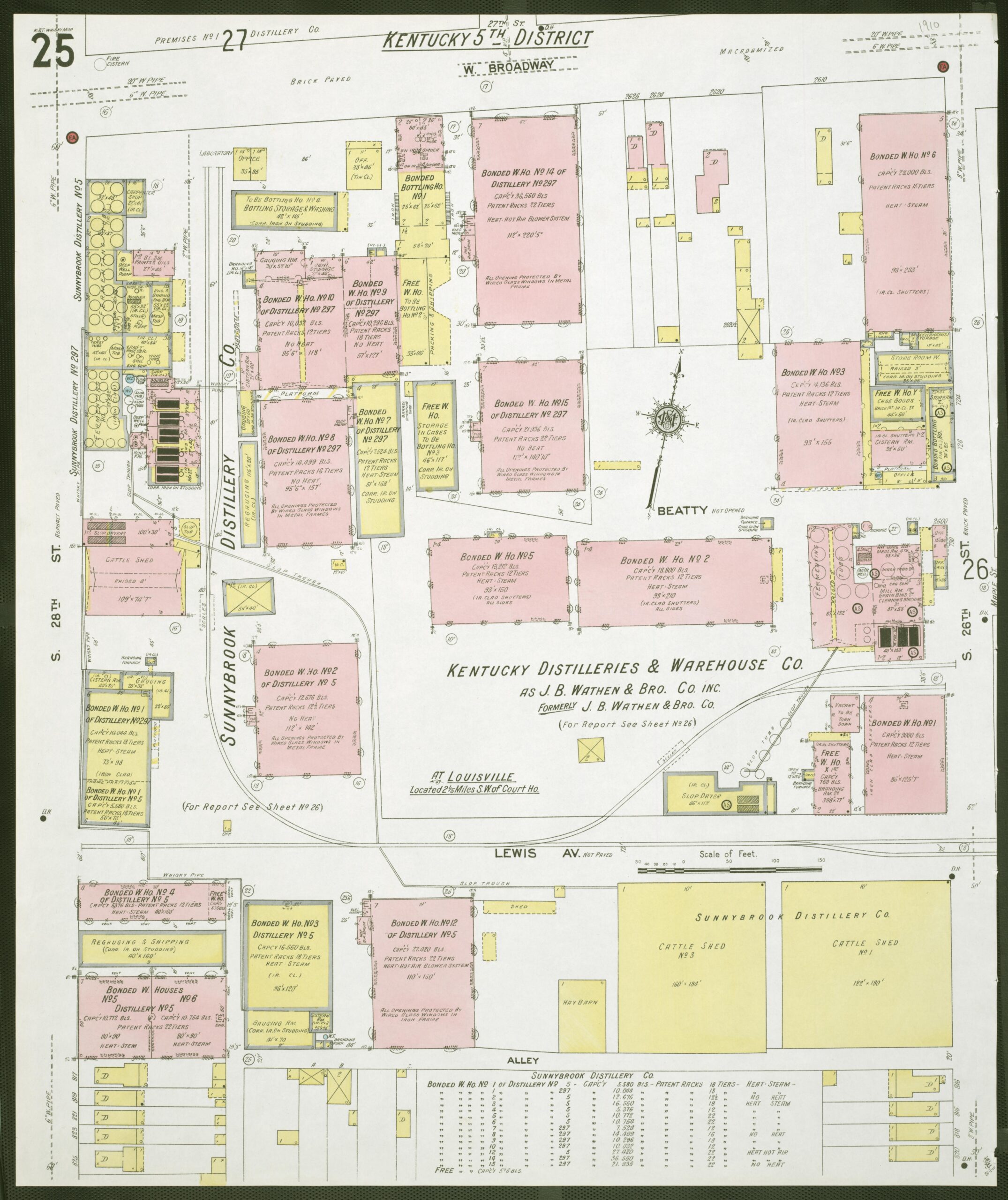

While Richard N. Wathen maintained an ownership stake in the tandem plants in Lebanon, John B., Sr. sold his shares back to his partners in 1880 and left Marion County to launch his own distillery at 26th and Broadway Streets in Louisville.

Nace took to the family business quickly. He assumed a secondary industry role as an Internal Revenue gauger in 1882, working under Attila Cox for the 5th district of Kentucky. Historic references show M.A. Wathen working as gauger between 1882 and 1886, but he is also quoted by newspaper journalists as the “secretary for the J.B. Wathen & Bro. Company” during those years, so he likely kept a foot in both camps. By the 1890s, M.A. Wathen had become a political creature in Louisville- not just as a government-employed tax collector, but as a member of Louisville society and its elite clubs.

In 1899, when the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (ASMC) acquired the J.B. Wathen Distillery at 26th and Broadway in Louisville, J.B. Wathen, Sr. was forced into retirement. The sale included a contract which gave the ASMC trademark rights to J.B. Wathen’s name- and it ALSO insisted that the 55-year-old J.B., Sr. cease all distilling-related activity within the whiskey industry for the next ten years! The contract couldn’t stop J.B.’s sons, however. The next year (1900), Nace’s nephews (Richard Eugene (R.E. Wathen), John Bernard, Jr., and Otho Hill (O.H. Wathen)) opened their own distillery in Louisville, calling it the R.E. Wathen Distillery. The fourth generation of Wathen distillers were ready to stake their claim in the industry.

In 1899, when the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (ASMC) acquired the J.B. Wathen Distillery at 26th and Broadway in Louisville, J.B. Wathen, Sr. was forced into retirement. The sale included a contract which gave the ASMC trademark rights to J.B. Wathen’s name- and it ALSO insisted that the 55-year-old J.B., Sr. cease all distilling-related activity within the whiskey industry for the next ten years! The contract couldn’t stop J.B.’s sons, however. The next year (1900), Nace’s nephews (Richard Eugene (R.E. Wathen), John Bernard, Jr., and Otho Hill (O.H. Wathen)) opened their own distillery in Louisville, calling it the R.E. Wathen Distillery. The fourth generation of Wathen distillers were ready to stake their claim in the industry.

The Whiskey Trust may have assumed ownership of the family’s largest distillery, but the Wathen family wasn’t going anywhere. Richard Nicholas Wathen was still in Lebanon at his Rolling Fork Distillery. James Abell Wathen, Nace’s only younger brother, who had been head distiller for his brothers in Lebanon before moving to Louisville to operate the J. B. Wathen Distillery, chose to remain in Louisville as an employee of the Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Company (subsidiary of the ASMC). The family would take advantage of the industry shakeup that came from Whiskey Trust’s massive acquisitions before the turn of the century. And when one of Kentucky’s finest distilleries was up for grabs in the late spring of 1899, the well-connected Martin “Nace” Wathen was ready to scoop it up.

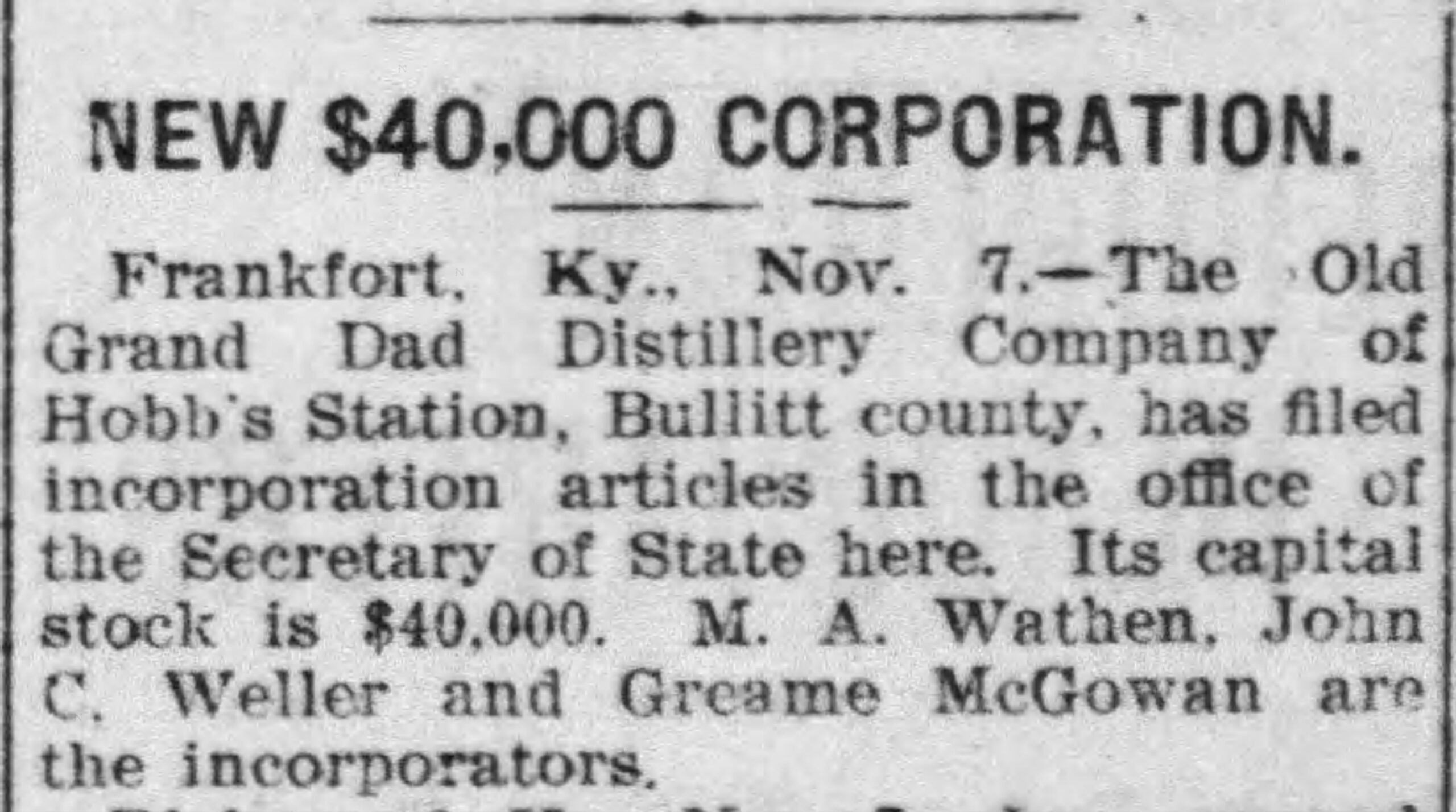

In April 1899, the R.B. Hayden Distillery in Hobbs Station near Bardstown had been sold to James L. Hackett of the Greenbrier Distilling Company. Hackett planned to flip the property and began entertaining offers almost immediately. Nace Wathen partnered with Graeme McGowan, sec./treasurer of the Greenbrier Distilling Co., and John C. Weller, son of W.L. Weller, to make the purchase. In November 1899, the men incorporated the Old Grand Dad Distilling Company of Hobbs Station with a capital stock of $40,000.

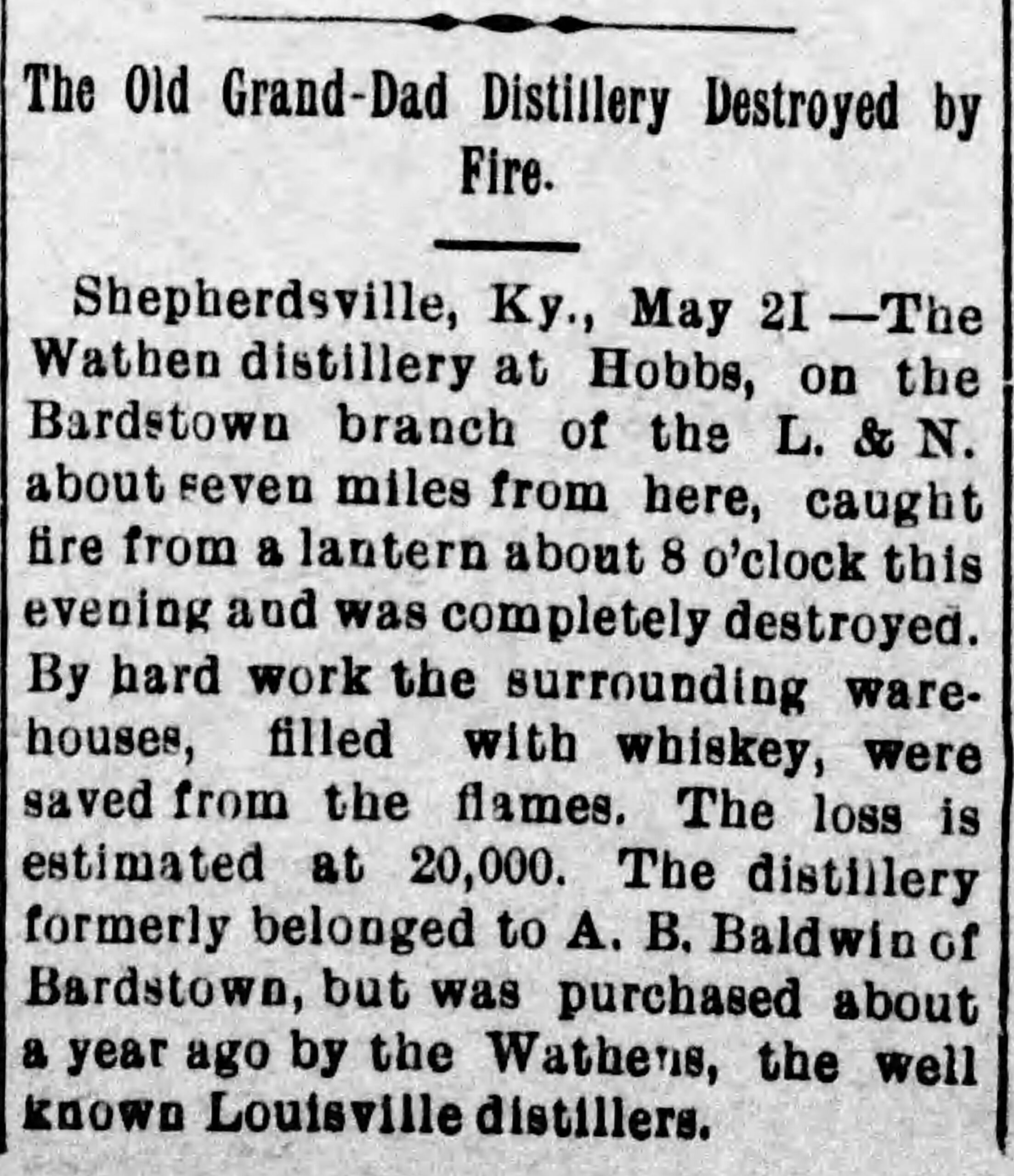

One year later, an exploding lantern set fire to the Old Grand Dad Distillery. The $20,000 in damage forced Nace Wathen to rebuild, so he erected a more modern sour mash facility with a 400-bushel capacity. R.E. Wathen invested in the distillery as well- some references say Nace and his nephew were equal partners in the firm. It’s important to note that while Nace Wathen had every intention of maintaining the integrity of the Old Grand Dad brand, he could not help but change the whiskey by modernizing it. M.A. Wathen continued to manufacture Old Grand Dad until his death in 1912. His nephew, J.B. Wathen, Jr. assumed proprietorship of the distillery after his passing. The distillery would be managed by J.B., Jr., R.E., and O.H. Wathen into Prohibition. Through scandal and the eventual abandonment of the Hobbs Station distillery in the early 1920s, the Wathens secured the famous Old Grand Dad brand for generations to come.

Next, we will discuss the origins of Old Grand Dad whiskey and how it evolved over time.

Old Grand Dad. Part 4.

History and Process.

“Old Grand Dad”, like most legacy whiskey brands, has a complex history which evolved over several generations of ownership. We’ve established that the modern version “Old Grand Dad” is a bourbon whiskey, made at the James B. Beam Distilling Co.’s plant in Clermont, which is owned by Suntory Global Spirits. It’s a unique product for the company- made with its own yeast strain and a “higher rye” bourbon mash bill of 63% corn, 27% rye, and 10% malted barley. The whiskey is distilled using a column still and matured in new oak at 120 barrel-entry proof somewhere inside Beam’s 126 rickhouses in Kentucky. When the brand was bought by American Brands, Inc. (Beam was a subsidiary) in 1987, they made efforts to reproduce National Distillers’ recipe for “Old Grand Dad”. At the new location in Clermont, Booker Noe did his best to reproduce the process of making Old Grand Dad as it had been made in Frankfort by National Distillers. Ironically, Beam’s Clermont location provided a more historically accurate home for Old Grand Dad than Frankfort ever could. Beam literally brought Old Grand Dad home by moving it back to Bulleit County- or at least as close to its old home at Hobbs Station site as possible. (See Part 2 for location information.) Being back in Bulleit County was one thing, but the whiskey would never be the same. Naturally, Old Grand Dad has changed many times since it was introduced in the 1880s. Let’s look at some of those changes by starting at the beginning.

“Old Grand Dad”, like most legacy whiskey brands, has a complex history which evolved over several generations of ownership. We’ve established that the modern version “Old Grand Dad” is a bourbon whiskey, made at the James B. Beam Distilling Co.’s plant in Clermont, which is owned by Suntory Global Spirits. It’s a unique product for the company- made with its own yeast strain and a “higher rye” bourbon mash bill of 63% corn, 27% rye, and 10% malted barley. The whiskey is distilled using a column still and matured in new oak at 120 barrel-entry proof somewhere inside Beam’s 126 rickhouses in Kentucky. When the brand was bought by American Brands, Inc. (Beam was a subsidiary) in 1987, they made efforts to reproduce National Distillers’ recipe for “Old Grand Dad”. At the new location in Clermont, Booker Noe did his best to reproduce the process of making Old Grand Dad as it had been made in Frankfort by National Distillers. Ironically, Beam’s Clermont location provided a more historically accurate home for Old Grand Dad than Frankfort ever could. Beam literally brought Old Grand Dad home by moving it back to Bulleit County- or at least as close to its old home at Hobbs Station site as possible. (See Part 2 for location information.) Being back in Bulleit County was one thing, but the whiskey would never be the same. Naturally, Old Grand Dad has changed many times since it was introduced in the 1880s. Let’s look at some of those changes by starting at the beginning.

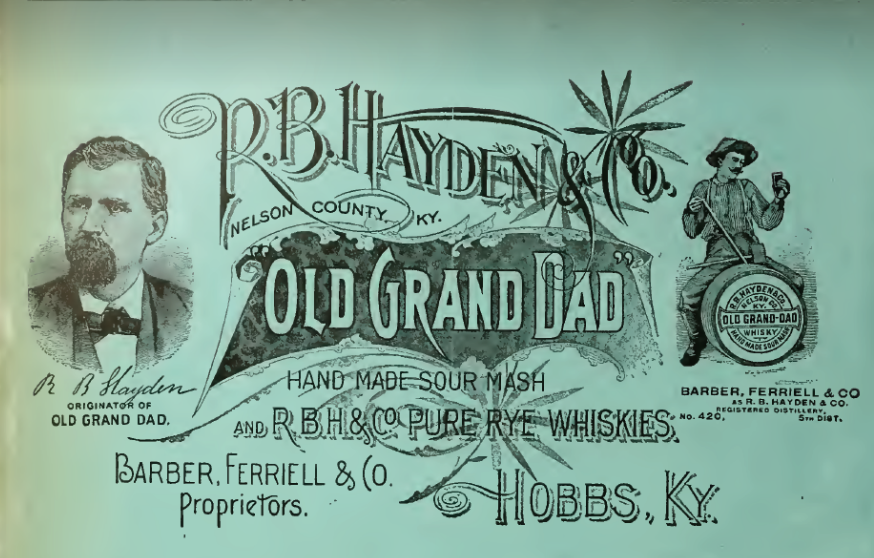

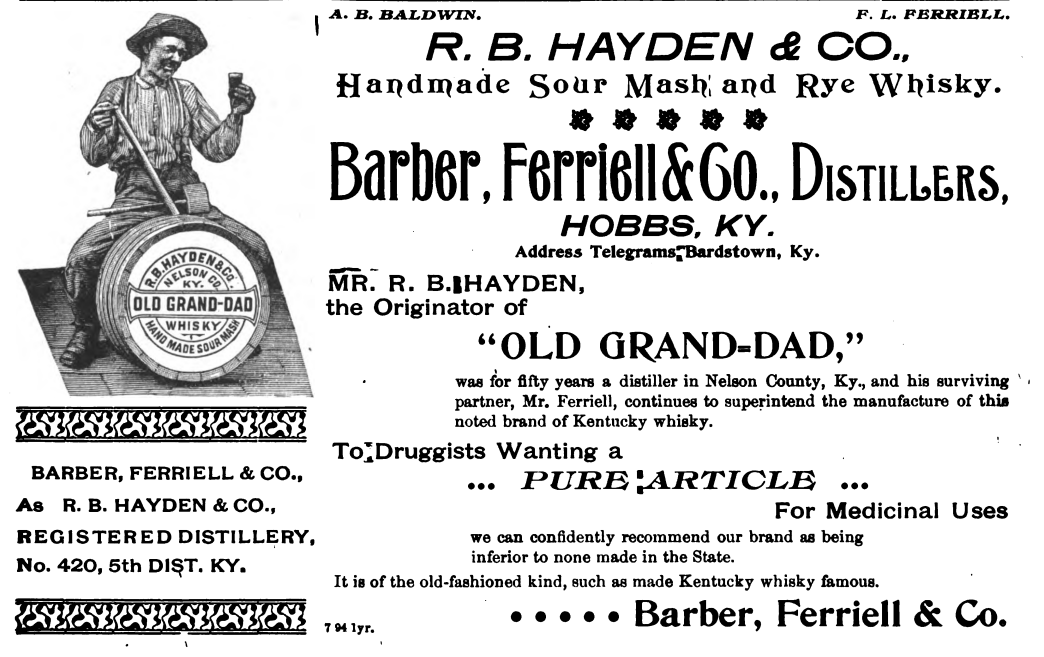

“Old Grand Dad” was first introduced to the market in the early 1880s.* The men behind the brand were Raymond Bishop Hayden and Francis Lemuel “Lem” Ferriell. It’s unclear how these natives of Marion County came to know one another, but Raymond and Lem were both known for their ability to distill whiskey. Oddly enough, Lem Ferriell had MORE to do with the preservation of the brand than R.B. Hayden! It is shameful that Ferriell’s contributions to the “Old Grand Dad” brand have been so overshadowed by the Haydens in the history books.

Raymond Bishop Hayden was the son of Wilford Lewis Hayden and the grandson of the famous Basil Hayden, Sr. who established the first Catholic settlement in Kentucky in 1785 at Holy Cross. Basil Hayden, Sr. led 60 families from Baltimore (through Pittsburgh and down the Ohio River on flatboats) to a settlement in Washington County near Pottenger’s and Cartright’s Creeks. (Marion County was carved from Washington County in 1834.) Basil Hayden, Sr. owned a great deal of land outside of Bardstown and owned slaves- all of which (and whom) he passed down to his surviving family members after his death in 1804. Basil’s son, Wilford Lewis Hayden, helped to maintain his father’s farmland and made whiskey on a piece of property about 3 miles south of Bardstown, presumably for local consumption. (This would later become the Boone Bros. Distillery, RD #422 after R.B. Hayden’s death)

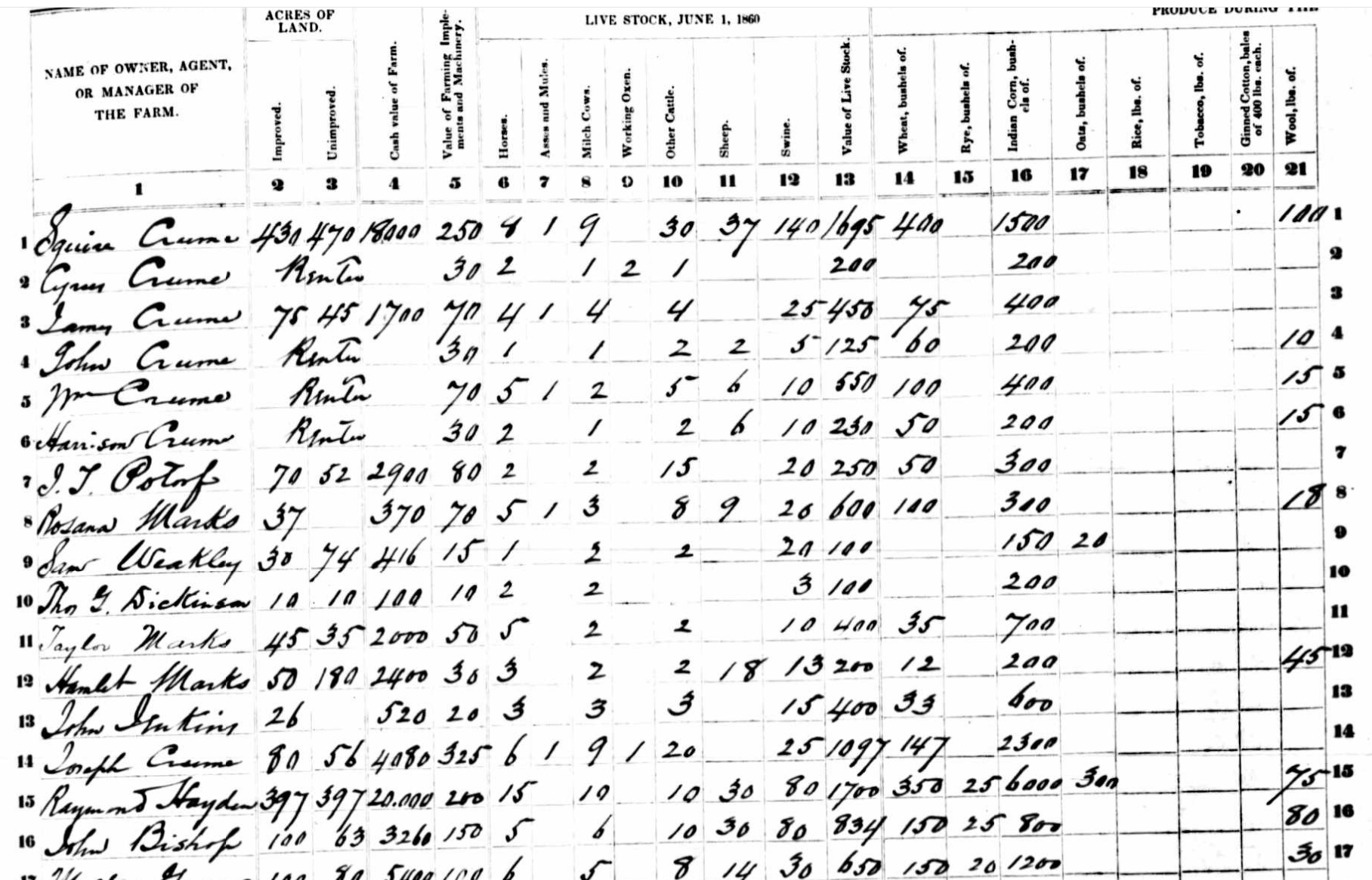

Lewis Hayden married Mary “Polly” Dant in 1810. The couple had many children, most of whom remained with their mother on the Hayden family’s farmstead into their adulthood. Lewis and Polly’s son, Raymond, became the head of the household after his father’s death in 1849. The Haydens were wealthy slaveowners and owned some of the largest and most valuable properties in Washington and Nelson Counties. It’s worth noting here that tax assessments for Raymond Hayden in 1860 DO NOT describe a great deal of rye on his property, though he was one of only a handful of farmers to have any rye at all! The tax records from June 1860 record the grains that were being stored on Raymond’s farm and their amounts: 300 bushels of oats, 350 bushels of wheat, 6,000 bushels of Indian corn, and only 25 bushels of rye. These tax records do not support the theory that he was using a high rye recipe for his whiskey, but the amount of corn certainly implies that it would have been made with mostly Indian corn!

The Civil War took its toll on the Hayden family. Raymond’s younger brother, Basil Hayden, Jr., was so upset over the loss of his slaves that he swore an oath to never touch soil again- for as long as he lived! He was true to his word, became a “hermit”, and was ridiculed as a local oddity for his decision to cut himself off from society. The farm lost value after the war, but Raymond refocused his efforts into enlarging his distilling business. He moved his home and his distilling operations to a 780-acre farm in Nelson County about 6 miles east of Bardstown and began distilling in earnest. When Raymond was in his 60s, he chose to partner with a younger distiller and ex-gauger named Francis Lemuel (“Lem”) Ferriell. Lem was the eldest son of Thomas Samuel Ferriell, an important figure in Marion County. He fought as a soldier for the Union during the Civil War and became a government-appointed gauger in the years after the war. Raymond and Lem decided that scaling up production would require a more advantageous location for their distillery.

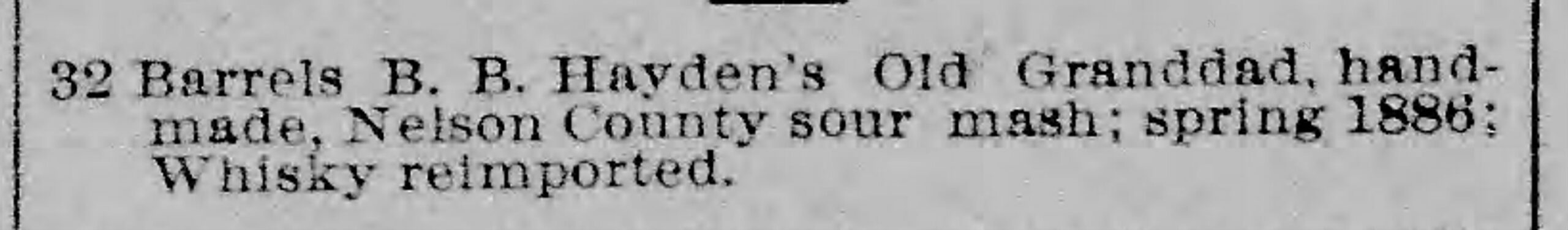

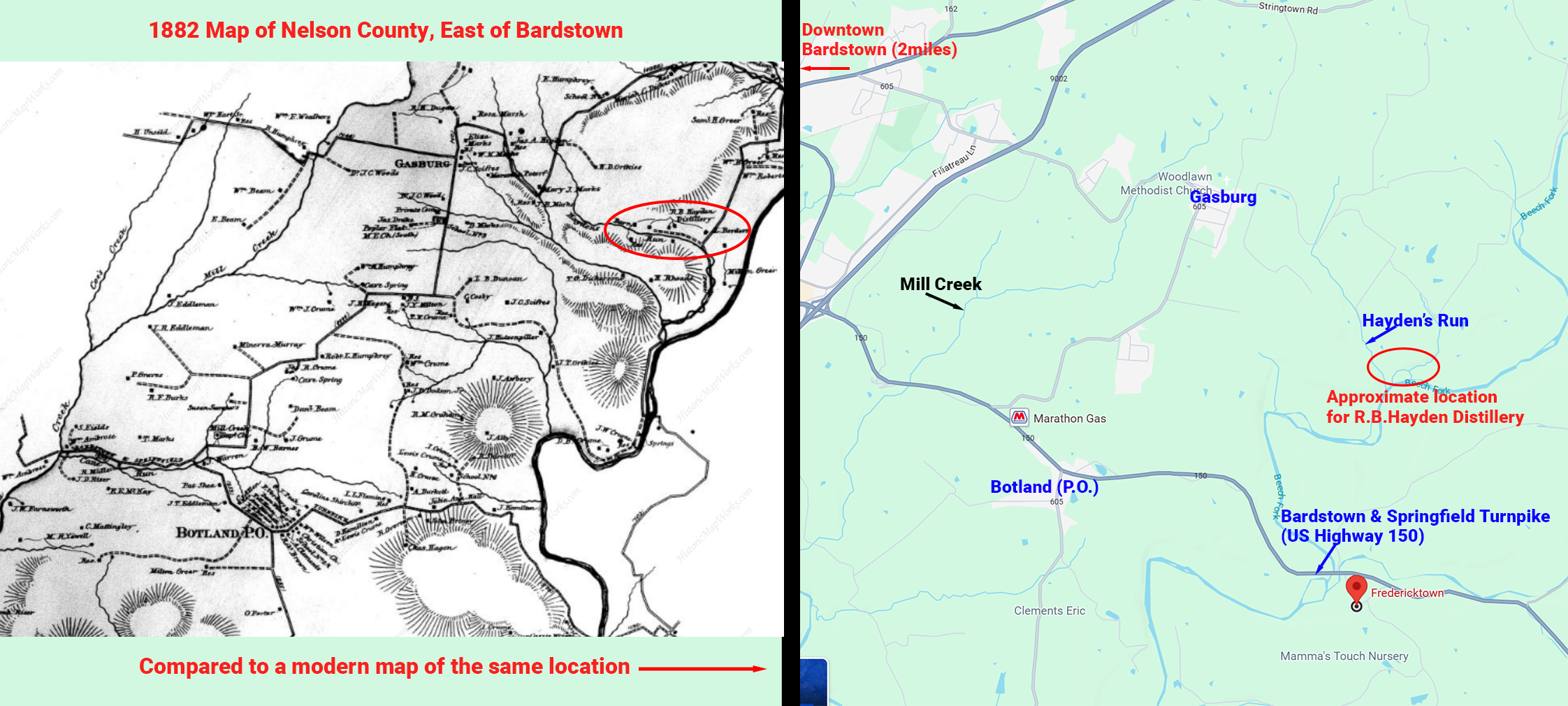

In 1882, R.B. Hayden and F.L. Ferriell built a new, 100-bushel capacity distillery with immediate access to the Louisville & Nashville Railroad at Hobbs Station, 12 miles northwest of Bardstown in Bulleit County. Most accounts describing the origins of “Old Grand Dad” whiskey mark this move and the founding of this new distillery as the year the “Old Grand Dad” brand was established. Is it likely that Raymond chose this moment to honor his grandfather by naming the whiskey he’d manufacture at Hobb’s Station “Old Grand Dad?” Or would the brand come a few years later? Either way, the future seemed bright for Raymond and Lem…until tragedy struck.

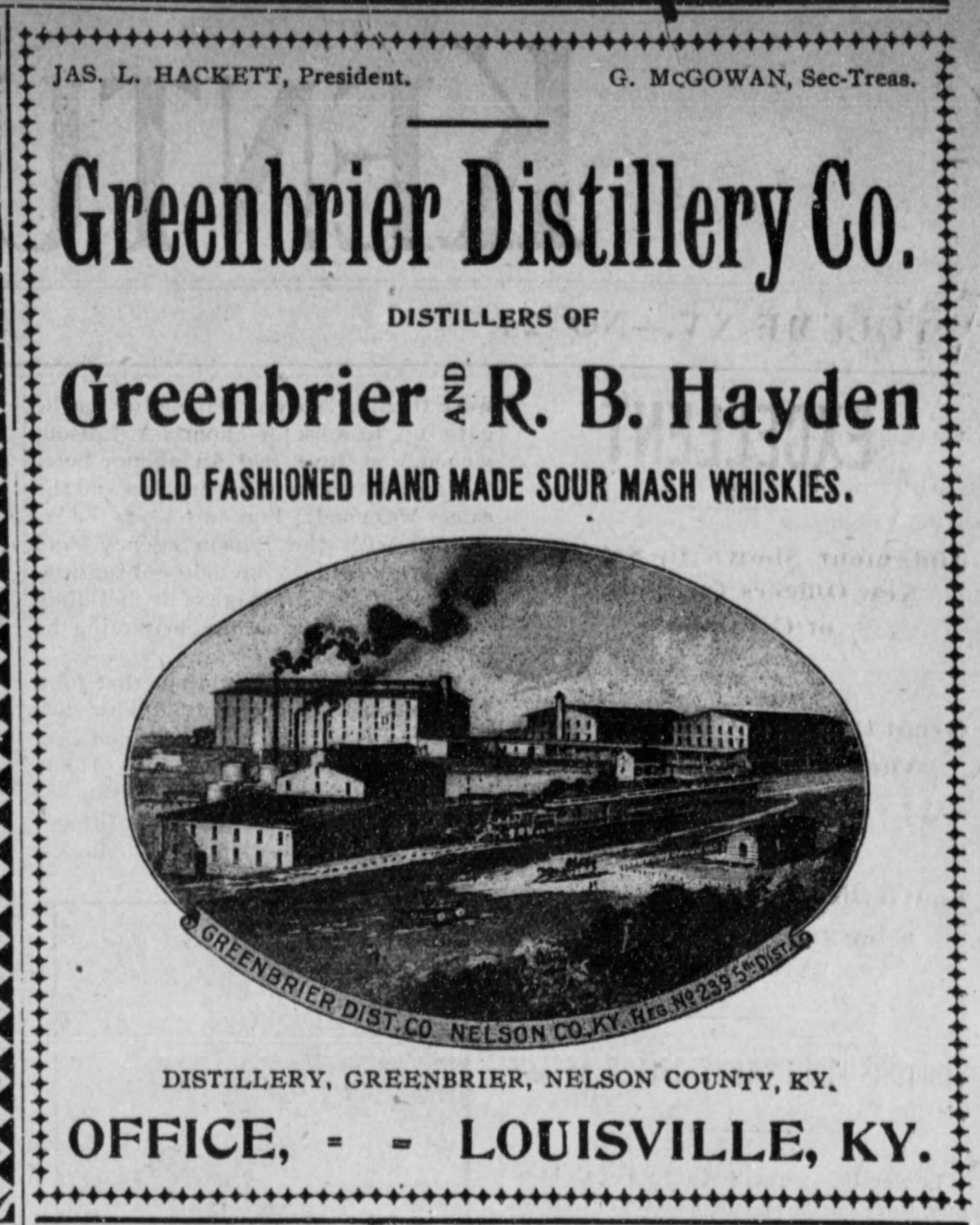

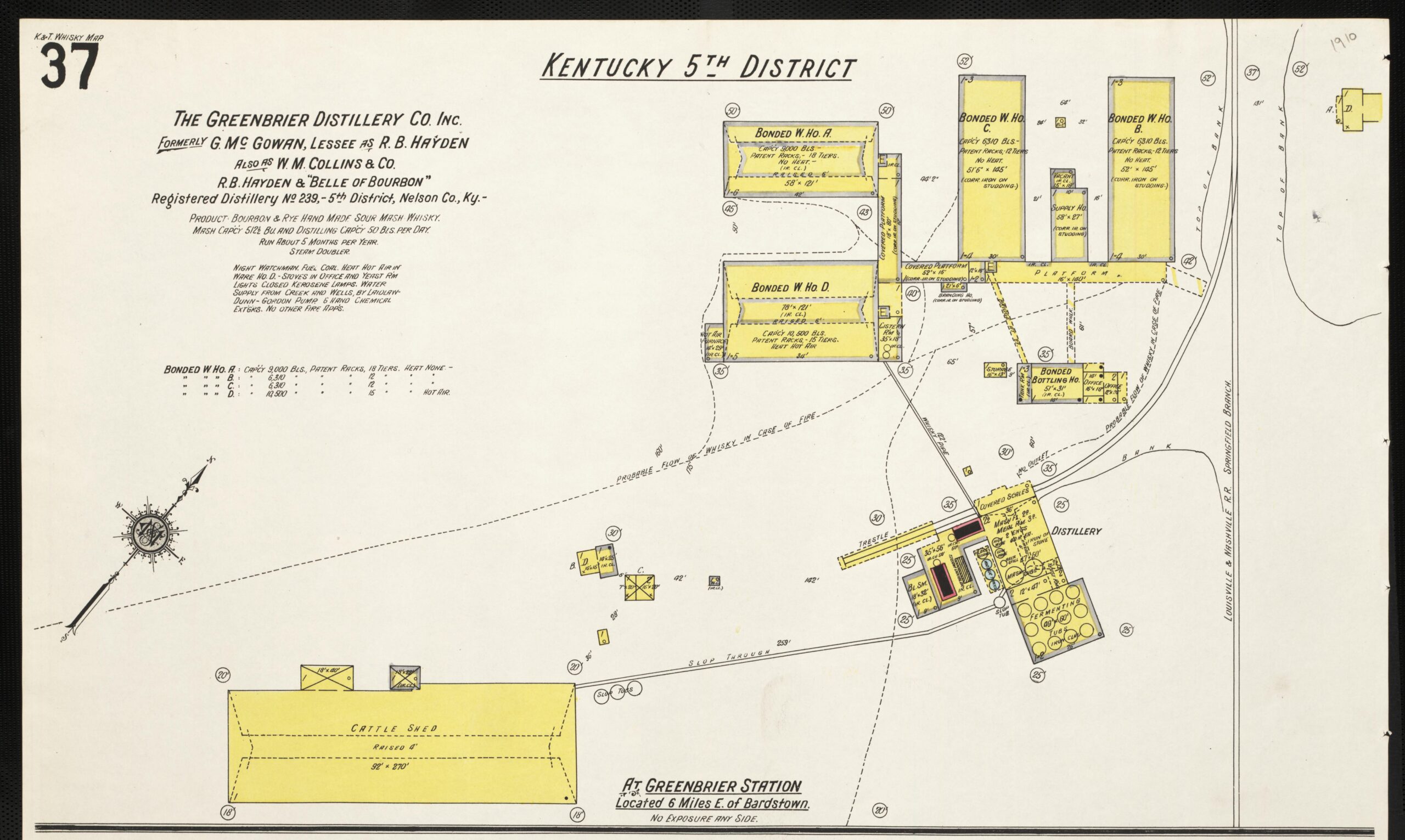

On June 11, 1885, Raymond was found dead in an orchard near his home (see 1882 map of distillery and property 6 miles east of Bardstown below). There was a bottle of poison found beside his body, so his death was deemed a suicide- even while some locals suspected foul play. R.B. Hayden was unmarried and had no heirs, so the following year (1886), the distillery property where he and Lem had built their distillery was sold in a commissioner’s auction. Lem Ferriell found a new partner in Philetus S. Barber, Esq., and together they purchased the property and resumed operations as Barber, Ferriell & Co. Raymond’s first distillery location near Beech Creek, 3 miles south of Bardstown, was sold at a separate commissioner’s auction in 1887, and it sold to the Boone Bros. R.B. Hayden’s distillery location 6 miles east of Bardstown, known as the “Belle of Bourbon Distillery”, was sold to Graeme McGowan and his Greenbriar Distilling Company. (See maps and images below. While R.B. Hayden’s first two distilleries did not manufacture “Old Grand Dad” whiskey, the distilling that took place on those properties surely influenced how “Old Grand Dad” would be made in the 1880s at the Hobbs Station plant.)

On June 11, 1885, Raymond was found dead in an orchard near his home (see 1882 map of distillery and property 6 miles east of Bardstown below). There was a bottle of poison found beside his body, so his death was deemed a suicide- even while some locals suspected foul play. R.B. Hayden was unmarried and had no heirs, so the following year (1886), the distillery property where he and Lem had built their distillery was sold in a commissioner’s auction. Lem Ferriell found a new partner in Philetus S. Barber, Esq., and together they purchased the property and resumed operations as Barber, Ferriell & Co. Raymond’s first distillery location near Beech Creek, 3 miles south of Bardstown, was sold at a separate commissioner’s auction in 1887, and it sold to the Boone Bros. R.B. Hayden’s distillery location 6 miles east of Bardstown, known as the “Belle of Bourbon Distillery”, was sold to Graeme McGowan and his Greenbriar Distilling Company. (See maps and images below. While R.B. Hayden’s first two distilleries did not manufacture “Old Grand Dad” whiskey, the distilling that took place on those properties surely influenced how “Old Grand Dad” would be made in the 1880s at the Hobbs Station plant.)

Barber, Ferriell & Co., operating as the R.B. Hayden Distillery even after Raymond’s death, were filling about 1000 barrels per year in the late 1880s. The Bonfort’s Wine & Spirit Circular published an article written on December 9, 1887- It poetically described the R.B. Hayden Distillery at Hobbs Station and provides production details on how “Old Grand Dad” was being made in the 1880s:

“A pretty distillery and an excellent warehouse, situated at a bend on the railroad, down in a spot where nature is at her best. Down the hill at this point, almost perpendicular from the distillery and warehouses, shaded by giant trees, beneath whose branches many a deer has sought relief from burning summer sun, three springs, of inexhaustible capacity, of the greatest purity, clear as a crystal, and with a summer temperature of fifty-two degrees, burst from the solid rocks. Such water it seems to me I never tasted, and surely had a Prohibitionist seen me drink of it his soul would have been delighted. At this spot the ‘Old Grand Dad’ whisky of R. B. Hayden & Co. is made by Messrs. Barber, Ferriell & Co.

“Not everyone who reads the CIRCULAR will recognize this brand of whisky, for the simple reason that the small crop made each year suffices only for the fortunate few, who divide it among themselves. It’s a most excellent whisky, though; a connoisseur’s whisky, if I may use the term. It is a clear whisky, rich and full- bodied. It touches the palate gently, and yet satisfies the taste. It is a splendid bar whisky straight, and still it has sufficient body to stand liberal cutting. It is a sour mash, fire copper, and mashed in small tubs. One peculiarity in the manufacture of this whisky is that two doublers are used. The second is charged about half full of low wines, and the vapor from the first is run through them. This prevents spewing, and seems to purify the spirit in every way. The first doubler is directly over a wood fire. The warehouse is an iron-clad building, and the whisky is stored in patent ricks far above the ground, most of it gaining from four to six degrees in proof.

“No drayage is charged on whisky, and shipments are promptly made.

“Of the crops previous to ’86, Messrs. Barber, Ferriell & Co. tell me every barrel has gone into consumption, not one being exported. The following lots represent all of these goods for sale at the present time, viz: of crop of ’86, 726 barrels; of crop of ’87, 1411 barrels.

“Dealers desiring to control the sale of a fine, sour mash Kentucky whisky, cannot do better than to secure control of the product of this distillery. The whisky is of the best quality; it is well coopered and stored, and promptly delivered, and the warehouse receipts are safe, as hundreds of thousands of dollars are behind the company. Samples of the whisky, with prices, etc., can be obtained by addressing Barber, Ferriell & Co., Hobbs, Kentucky. The whisky speaks for itself.” (- M. Ligmot)

High praise, indeed- “A connoisseur’s whiskey”! Note the use of small fermentation tubs and the use of a wood fired copper pot still with two doublers! This style of whiskey is far removed from what Old Grand Dad would become in the 20th century. Another important thing to note is the sale of “Old Grand Dad” at wholesale and as young whiskey with vintage years. Its limited availability gave it prestige and placed it in high demand among wholesale buyers. It had “sufficient body to stand liberal cutting” which would have appealed to rectifiers looking to use it in blends. This whiskey, made by Lem Ferriell, had already earned an enviable reputation- and this article was written JUST TWO YEARS after R.B. Hayden’s death. The brand was already developing a life of its own, entirely separate from the Hayden family, even if the name of the distillery suggested otherwise.

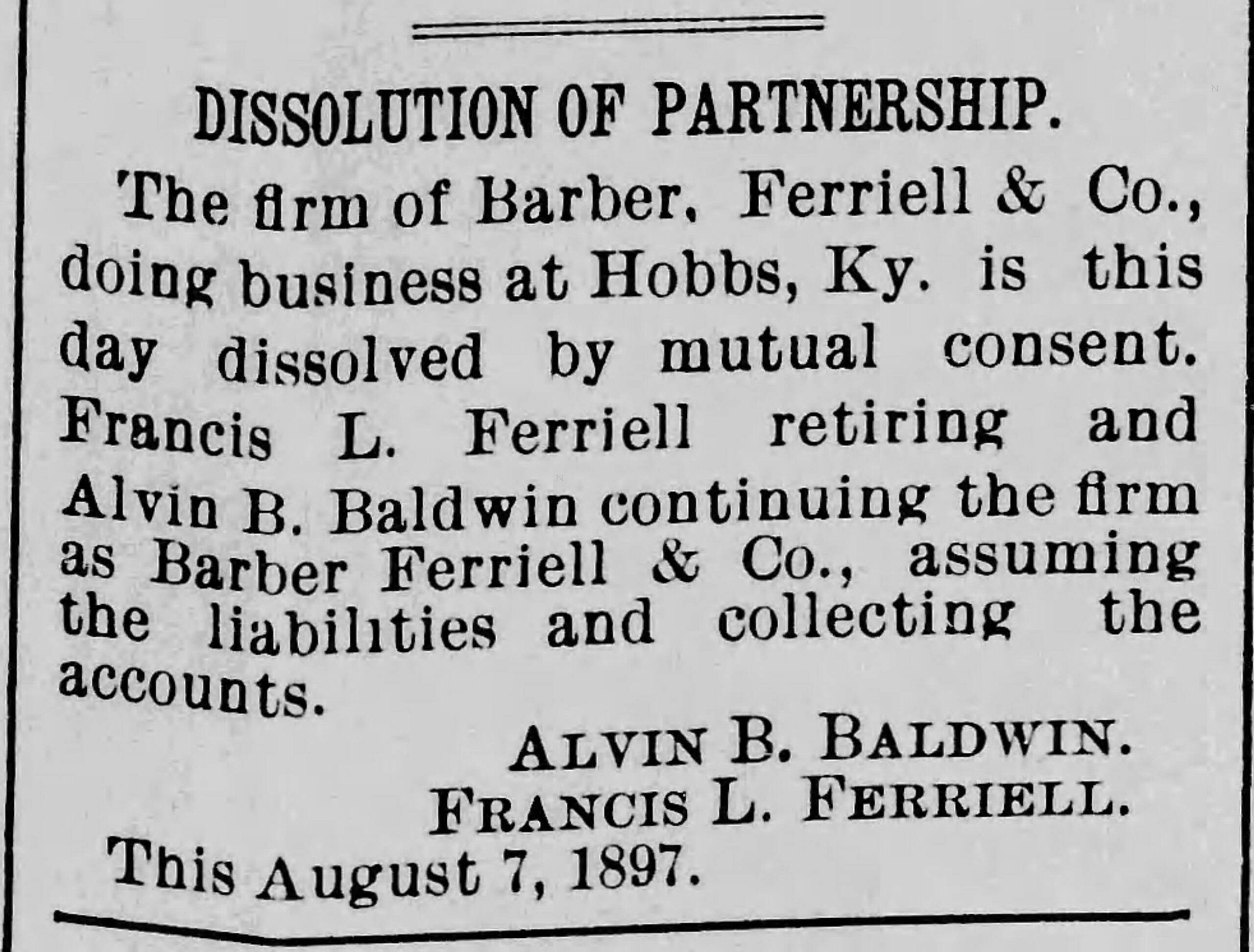

Philetus S. Barber, noted as the wealthiest man in Nelson County, passed away in 1894. Barber’s ownership stake in the R.B. Hayden Distillery at Hobbs Station passed to his son-in-law, Alvin B. Baldwin. F.L. Ferriell remained business partners with A.B. Baldwin until 1897 when Lem retired, and the partnership was dissolved.

In 1899, Baldwin sold the distillery to the Greenbrier Distilling Co. who quickly flipped it by selling to M.A. Wathen. To be clear, Graeme McGowan, sec./treasurer of the Greenbrier Distilling Company, did not divorce himself from the “Old Grand Dad” brand through the sale of the Hobbs Station plant to M.A. (Nace) Wathen. Instead, he partnered with Nace Wathen and John C. Weller to form the “Old Grand Dad Distilling Company” in November 1899! The rest is history…and explained in Part 1, 2, and 3!😊

A curious addition to this story- I’ve mentioned the Greenbrier Distilling Company before in my write up on the Schreiner family of distillers! R.B. Hayden’s Distillery east of Bardstown- the one that became the Greenbrier Distillery after R.B. Hayden’s death by poison? That distillery was disassembled in 1922 and shipped to Canada to become the LaSalle Distillery in Montreal! And for all the whiskey collectors out there- Yes, the pints of Greenbrier whiskey were distilled at the “Belle of Bourbon Distillery”(R.D. #239) which was originally owned by R.B. Hayden until he died by poisoning in the orchard on that property, but NO, it was NOT made like “Old Grand Dad” any more than any bourbon made in Nelson County was made like “Old Grand Dad”.

Old Grand Dad whiskey has obviously changed a great deal over the years, but where did the “high rye mashbill” come from? I have a theory that seems to make a lot of sense, and I’ll tell you all about it in my next post!

*Any suggestion that it was introduced in 1840 is false. That date approximates the year that Lewis and Raymond Hayden may or may not have begun distilling whiskey on their property 3 miles south of Bardstown in Nelson County. “Old Grand Dad” was never produced on that site. That farm would later become the Boone Bros. Distillery, RD #422, after the property was sold in 1887 and after Raymond Hayden’s death.

** I’ve included two 1882 maps below- The distillery marked “R.B. Hayden’s Distillery” has a modern map showing its approximate location. The property marked “R.B. Hayden Res.” shows the location of R.B. Hayden’s original distillery. See attached article from 1901 acknowledging the location having belonged to the Boone Bros. and its sale to Thixton, Millet & Co.

Old Grand Dad. Part 5. (Finale)

The “High Rye” Mashbill.

I’m not the first person to question the truth behind Old Grand Dad’s historic recipe. Was it really always a high rye mashbill? Is that the way Basil Hayden really made it? And if it’s not, how did the modern version of Old Grand Dad come to be what it is today?

Old Grand Dad and Basil Hayden whiskeys are made at the James B. Beam Distilling Co.’s plant in Clermont using the same distillate- so same yeast, same mashbill, same spirit off the still. The differences between the “Old Grand Dad” and “Basil Hayden” brands are determined after distillation- in the barrel, the position of that barrel in the warehouse, and the final bottling proof. (Basil Hayden has also branched into a seemingly endless number of barrel finishes, as well.) This slight differentiation between brands is historically normal for the whiskey industry; Competing whiskey companies would often buy barrels of whiskey at wholesale from the same distillery and mature it under their own unique conditions or rectify the same whiskey slightly differently to create their own twist on a the same distillate. In fact, I pointed out yesterday that Old Grand Dad was a wholesale product being sold to the independent bottlers and rectifiers. Today, Old Grand Dad and Basil Hayden whiskeys ARE different. They taste different from one another, and they taste different from other bourbons on the market. Supposedly, it’s that “high rye mashbill” that’s setting them apart.

Beam’s website for Basil Hayden says this about the brand:

“This style of bourbon was inspired by 1792 whiskey pioneer Meredith Basil Hayden, Sr., a rye farmer from Maryland who moved to Kentucky and began distilling. He chose to distill his bourbon with a higher percentage of rye, and Booker set out to create a similar high-rye mash bill that would offer the same refined, approachable taste profile.”

There is no proof that Basil Hayden, Sr. was ever a rye farmer. He settled in Washington County, Kentucky in 1785. That 1792 date was the year Kentucky became a state. The part that DOES ring true here is the credit given to Mr. Booker Noe. Basil Hayden was released to the public in 1992 as one of four small batch whiskeys- Knob Creek for the bourbon sippers (9 year old, 100 proof), Basil Hayden for the Canadian whiskey drinkers (80 proof, lighter profile bourbon), Bakers for the bartenders (107 proof for mixing strength), and Bookers…well, for Booker- at cask strength. Only Basil Hayden was a high rye whiskey…it was a lighter version of Old Grand Dad and a way to rebrand an old classic.

Old Grand Dad had been made at Clermont by Booker Noe since 1987 when the brand was absorbed by American Brands, Inc; Booker made it, and he did his best to maintain the integrity of the brand when it was moved from Frankfort’s distillery on Elkhorn Creek (and its home for 47 years- 1940 to 1987) into his care at Beam’s Clermont Distillery. But why was Old Grand Dad being made with a high rye mashbill in Frankfort?! We’ve established that The Old Grand Dad Distillery in Frankfort was NOT the original home for Old Grand Dad, so how did that mashbill get there in the first place? Does it really seem plausible that National Distillers was SO integrity-driven that they prioritized the maintenance of Old Grand Dad’s original recipe? I mean…if they WERE trying to do that, why don’t we see any advertising material suggesting purpose behind a specifically rye-heavy formula for Old Grand Dad? In fact, ads describing “high rye” or rye-heavy bourbons don’t really appear until after Booker created Basil Hayden bourbon in 1992. To figure out where this high-rye recipe came from, we have to look at the history of the distillery at the Forks of the Elkhorn BEFORE National Distillers came to own it.

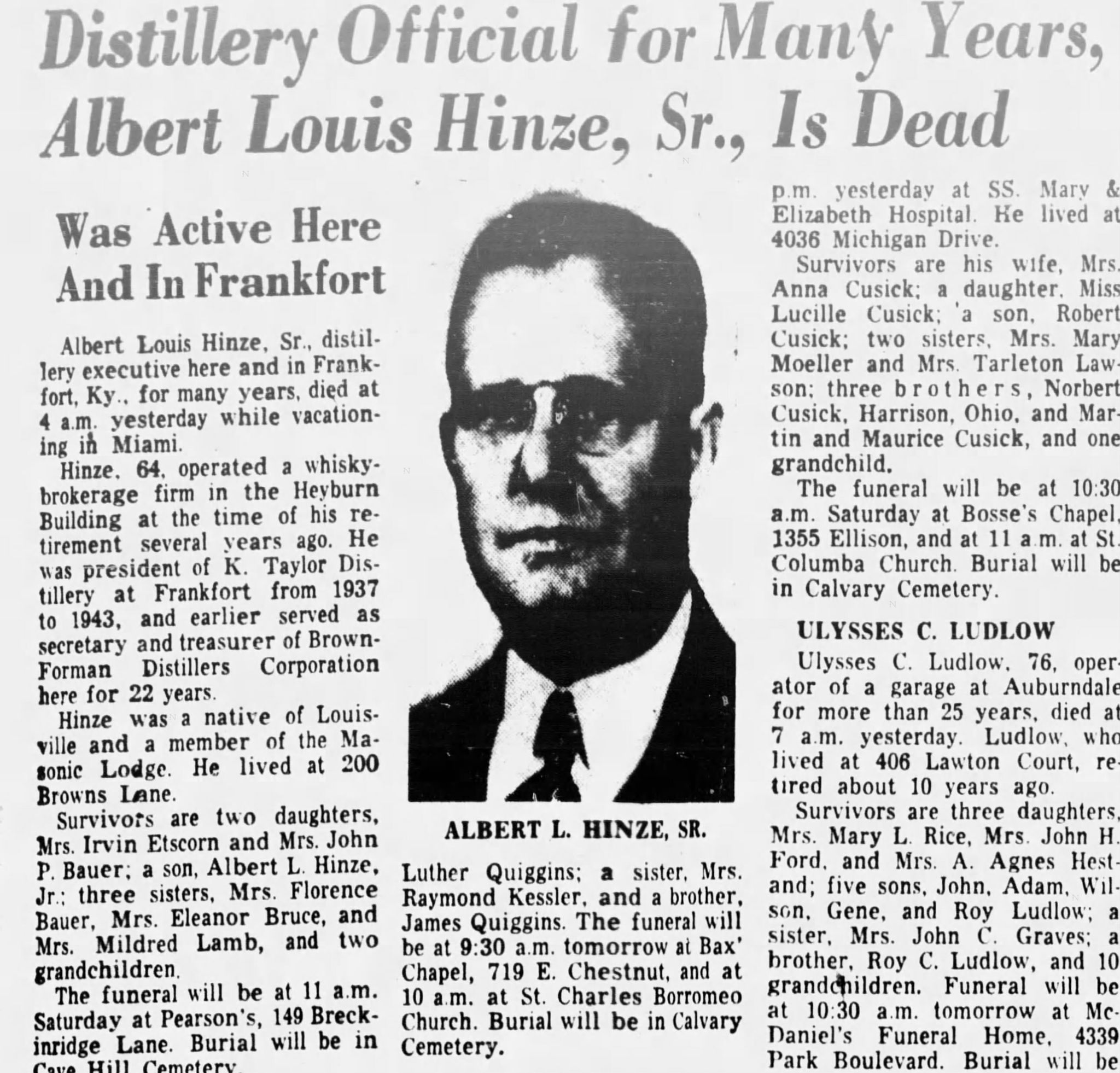

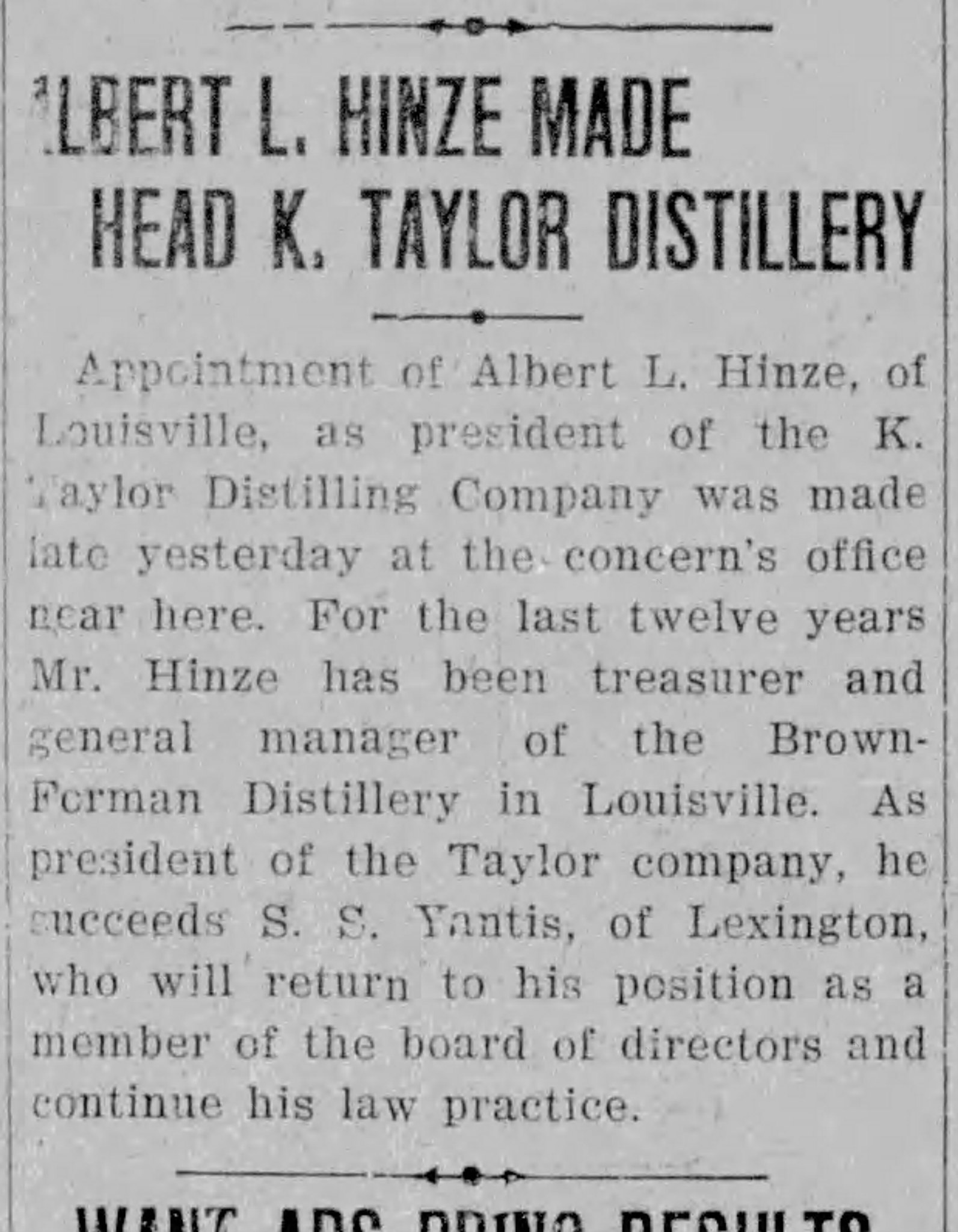

In December 1933, just after Repeal, the new owner of the old Frankfort Distillery was Kenner Taylor, son of E.H. Taylor, Jr. Kenner had been manager at his father’s Old Taylor Distillery (just outside of Frankfort on Glenn’s Creek) before Prohibition, but his post-Prohibition sights were set on renovating the old Frankfort plant on the Elkhorn. He renamed the plant, calling it the “K.Taylor Distillery”. Unfortunately for Kenner Taylor, he did not live to see the distillery completed. He died on June 1, 1934 at the age of 70 while the plant was still under construction. The K. Taylor Distillery was left leaderless even before the stills could be fired up! Between June and November 1934, a Lexington lawyer named S.S. Yantis filled a temporary leadership role, but by November, a man named Albert Louis Hinze stepped up to become K. Taylor’s new president. A.L. Hinze had been treasurer and manager of the Brown-Forman Distillery in Louisville since 1922. (Yes, during Prohibition!) He also handled sales, so Hinze had a clear vision for what his distillery could be.

When A.L. Hinze fired up the stills at K. Taylor for the first time on March 1, 1935, he was making a whiskey of his own design. Hinze had been taught to make and sell whiskey by Thomas S. Jones of Louisville. Jones had been owner/distiller at the old Coon Hollow Distillery and Big Spring Distilleries (aka the Nelson County Distilling Company) during the 1890s and secretary of the Kentucky Distillers Association (KDA) before Prohibition. His tenure with the KDA included lobbying to benefit the straight whiskey interests in Kentucky, especially during the late 1890s and early 1900s (Bottled-in-Bond Act, Pure Food and Drug Act, Taft Decision, etc.). Albert Hinze went to work for Thomas Jones in the years before Prohibition, learning everything he knew about distilling and brokering the sale of whiskey from him. That expertise landed him a job with the Brown Forman Company during the early years of Prohibition. Hinze remained with Brown Forman as the company’s secretary/treasurer and distillery manager until 1934. When Kenner Taylor died, Albert L. Hinze was ready to fill his shoes in Frankfort.

When A.L. Hinze fired up the stills at K. Taylor for the first time on March 1, 1935, he was making a whiskey of his own design. Hinze had been taught to make and sell whiskey by Thomas S. Jones of Louisville. Jones had been owner/distiller at the old Coon Hollow Distillery and Big Spring Distilleries (aka the Nelson County Distilling Company) during the 1890s and secretary of the Kentucky Distillers Association (KDA) before Prohibition. His tenure with the KDA included lobbying to benefit the straight whiskey interests in Kentucky, especially during the late 1890s and early 1900s (Bottled-in-Bond Act, Pure Food and Drug Act, Taft Decision, etc.). Albert Hinze went to work for Thomas Jones in the years before Prohibition, learning everything he knew about distilling and brokering the sale of whiskey from him. That expertise landed him a job with the Brown Forman Company during the early years of Prohibition. Hinze remained with Brown Forman as the company’s secretary/treasurer and distillery manager until 1934. When Kenner Taylor died, Albert L. Hinze was ready to fill his shoes in Frankfort.

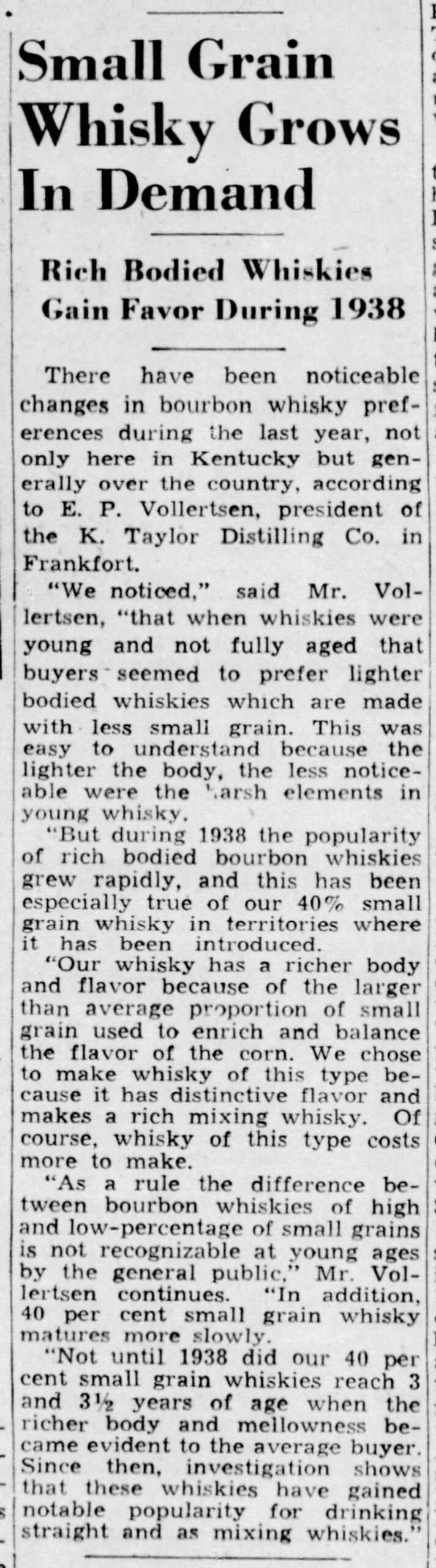

Albert Hinze’s first order of business at the K. Taylor Distillery was to fire up the stills in the spring of 1935. His formative years in the whiskey industry, learning from Thomas S. Jones clearly had an effect on him, because he set right to work making an expensive style of whiskey! He insisted upon the use of 40% small grains in his mashbill. A veteran whiskey broker during Prohibition, Hinze understood that the country’s whiskey drinkers would pay up for a high-quality whiskey. He also understood that a heavy-bodied whiskey could be sold in bulk at a higher rate to distilling companies seeking blending agents! The K.Taylor Distillery, often described as “Kentucky’s most beautiful distillery”, was, from the first day of its operation after Prohibition, making a HIGH RYE BOURBON!

Hinze remained president of the K. Taylor distillery until January 12, 1937 when he established his own brokerage firm to sell the whiskey he had a hand in manufacturing. His new company, the A.L. Hinze Distillery Company, was based out of the Heyburn Building in Louisville, Kentucky. Ever the savvy salesman, Hinze’s first big sales campaign for his new company was for “War Admiral Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey.” He could not have known that in the months following his sales campaign, (launched in early March after War Admiral won the Chesapeake Stakes in Havre de Grace on April 24, 1937) that War Admiral would become the 4th winner of the American Triple Crown! But his intuition was good and his whiskey was better. A company announcement before the Kentucky Derby in 1937 stated,

“Fine whiskies like thoroughbred horses- have proud pedigrees.

“A.L. Hinze Bourbon 40 Per Cent Small Grain is a whisky rich in tradition. A.L. Hinze is actively carrying onward in the making of fine whisky. Following the same straight path blazed by distillers of reputation under whom A.L. Hinze received his training, and adhering to the samr rigid precepts and principles that had their beginning long, long years ago.

“A.L. Hinze Bourbon 40 Per Cent Small Grain is an outstanding whisky. It is not an accident, but the result of careful planning, constant watchfulness, and painstaking care. It combines the two great gifts of nature; pure limestone water and carefully selected grain, by the art of the distiller, a master in his calling.

“A.L. Hinze Bourbon 40 Per Cent Small Grain is then laid away in new heavily charred white oak barrels. Over these Father Time waves his magic wand of passing years until the deep charred wood has done its share. Then from the barrel in full, rich, red, mellow glory there issues the greatest gift to the happiness of man, Kentucky burbon (sic) whisky, which brought fame to the Bluegrass State, its home and birthplace.”

A.L. Hinze essentially set up production at the Frankfort Distillery in the early 1930s, so even when he left to start his own firm, and E.P. Vollertsen took his role, the plant had its marching orders. Frankfort was manufacturing a high-rye bourbon in bulk.

A.L. Hinze essentially set up production at the Frankfort Distillery in the early 1930s, so even when he left to start his own firm, and E.P. Vollertsen took his role, the plant had its marching orders. Frankfort was manufacturing a high-rye bourbon in bulk.

In 1939, National Distillers sued the K.Taylor Distilling Co. for their use of the word “Taylor”, and by 1940, they had absorbed the company. National Distillers moved production of “Old Grand Dad” from where it was temporarily being made in Louisville (R.E. Wathen Distillery) to its new home in Frankfort, Kentucky. The K. Taylor was re-named “The Old Grand Dad Distillery”…and the rest is history.

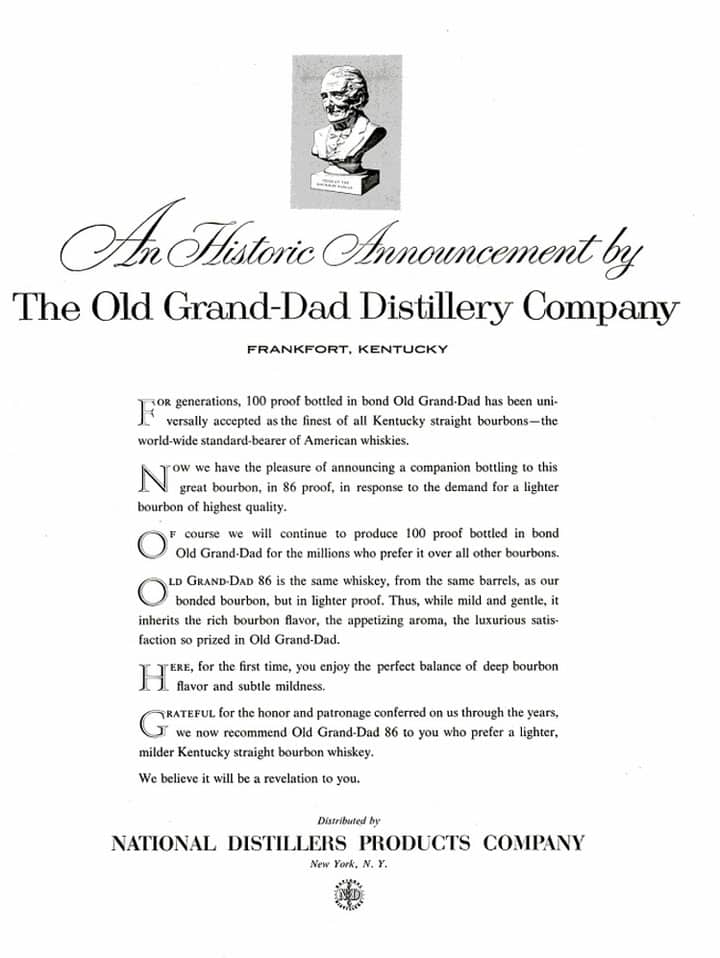

Some would argue that the best Old Grand Dad that was ever made was made while National Distillers owned the brand. They never even mentioned Basil Hayden or “high rye” in the 47 years the brand was in their possession. Immediately after Prohibition, when it was being manufactured at the R.E. Wathen Distillery in Louisville, National Distillers made no connection to Basil Hayden. That famous bust that was supposedly carved to look like Basil Hayden? There’s no proof it was anything more than a life-like rendering of the cartoonish figure on the brand’s label. The bust and its “Old Grand Dad” pedestal began appearing in ads around 1939 when National Distiller Products Co.’s campaign for Old Grand Dad was “Head of the Bourbon Brands.” “Head”…Get it? There are no portraits of Basil Hayden, Sr. for us to compare any likeness to the bust, anyway.

What I’m getting at here is that the whole “high-rye bourbon came from Basil Hayden” is a marketing angle that was devised in the 1990s. It was a great angle, mind you! Basil Hayden was from Maryland, and distillers made rye whiskey there. Basil Hayden went to Kentucky, so it makes sense that he would’ve used rye…but that is a huge stretch considering the fact that Raymond Hayden was only responsible for the brand for 3 years of his life (If that!), and the “Old Grand Dad” brand has existed and been manufactured at several different locations for almost 150 years! It just makes more sense that the distiller at K. Taylor Distillery in Frankfort established a recipe and mashing schedule for bourbon in the early 1930s, and National Distillers, when they absorbed the distillery and moved Old Grand Dad from Louisville to Frankfort, simply decided that “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” When Booker Noe took over the manufacture of Old Grand Dad for Jim Beam in Clermont, Ky (1987), he wanted to maintain the excellence that he had come to associate with Old Grand Dad bourbon- so he followed the same, tried and true methods that made it excellent…methods that had been taught to A.L. Hinze by Thomas S. Jones, a man who knew bourbon the way a seasoned veteran of the bourbon industry and president of the Kentucky Distillers Association should have known bourbon. He made it the way that bourbon’s old granddad made it. Maybe not the way Basil Hayden made it, but that shouldn’t matter.