Pennsylvania’s historically heavy bodied and aromatic pure rye whiskeys started with the grain. The rye grain grown today does not compare to the ryes that were used for distilling whiskey before Prohibition. Historically, rye grain was purposefully bred for milling and distilling purposes, and farmers sought out the rye varietals their customers wanted to buy. Distillers bought large quantities of rye grain in bulk and paid top dollar for it, so smart farmers grew what distillers preferred. Pennsylvania, in turn, became of the nation’s top rye growing states in the 19th century- all in service to the rye whiskey industry!

Rye plants are notorious for being promiscuous pollinators. The pollen which puffs off of its flowers (anthers) in the spring is carried off by the wind, often floating for miles into other rye fields on other farms. This cross-pollination of rye fields led to the creation of homogenous rye variations called “landrace grains”. Landrace varietals were not purposefully created by seed breeding farmers; They were created naturally over time, and they became unique to specific geographically isolated regions. While the concept of landrace rye still exists and many Pennsylvania farmers still choose to grow rye from personally maintained seedstocks, the reality is that the majority of farmers buy their seed each year from a seed broker who sources his/her seed from outside the state. The natural progression and creation of landrace varietals has largely come to a halt in modern times. Instead of saving seedstock, farmers have opted to buy their seed from a broker each year. They don’t intend to harvest the rye anyway, so the variety and quality of the rye has become irrelevant. Rye is rye,…right?

Rye plants are notorious for being promiscuous pollinators. The pollen which puffs off of its flowers (anthers) in the spring is carried off by the wind, often floating for miles into other rye fields on other farms. This cross-pollination of rye fields led to the creation of homogenous rye variations called “landrace grains”. Landrace varietals were not purposefully created by seed breeding farmers; They were created naturally over time, and they became unique to specific geographically isolated regions. While the concept of landrace rye still exists and many Pennsylvania farmers still choose to grow rye from personally maintained seedstocks, the reality is that the majority of farmers buy their seed each year from a seed broker who sources his/her seed from outside the state. The natural progression and creation of landrace varietals has largely come to a halt in modern times. Instead of saving seedstock, farmers have opted to buy their seed from a broker each year. They don’t intend to harvest the rye anyway, so the variety and quality of the rye has become irrelevant. Rye is rye,…right?

There is quite a lot of rye grown in Pennsylvania, but the vast majority of the rye being grown is not meant to be harvested the following summer. For decades, farmers, especially corn and soy farmers, have planted rye as a “cover crop”. A cover crop is literally that, meaning it is deliberately planted to cover the ground during the winter months, anchoring the topsoil and reducing erosion with rye’s long, dense root system.  The variety of rye used for this purpose is usually bagged and sold as an NVS (non-variety stated) rye varietal. To the farmer, the quality and character of the berries produced by NVS rye is immaterial, because the purpose of the plant lies in its ability to anchor nitrogen and create “green manure” for the soil. The NVS rye that overwinters in a field will usually be tilled back into the soil so that a commodity crop can be planted in its place. NVS ryes were never intended to be used for food and tend to be a greener and much less flavorful rye when used for distilling purposes. Distillers today often describe rye whiskey made from NVS grain as being “grassy” or “earthy” when what they really should be looking for in their rye whiskey (if they mean to recreate historic PA rye) is “fruity” and “floral.”

The variety of rye used for this purpose is usually bagged and sold as an NVS (non-variety stated) rye varietal. To the farmer, the quality and character of the berries produced by NVS rye is immaterial, because the purpose of the plant lies in its ability to anchor nitrogen and create “green manure” for the soil. The NVS rye that overwinters in a field will usually be tilled back into the soil so that a commodity crop can be planted in its place. NVS ryes were never intended to be used for food and tend to be a greener and much less flavorful rye when used for distilling purposes. Distillers today often describe rye whiskey made from NVS grain as being “grassy” or “earthy” when what they really should be looking for in their rye whiskey (if they mean to recreate historic PA rye) is “fruity” and “floral.”

In the mid- to late-19th century, when “Pennsylvania pure rye whiskey” production was in full swing, the favored rye grain of distillers was known as “Mammoth White” rye. That variety also became known as “Egyptian White Rye” as the Egyptian Revival era was ushered in. There was nothing Egyptian about the grain, but the name stuck for marketing purposes. (Consumers, including farmers, loved the association with anything “Egyptian”, hence the name.) These white ryes were bred for their elongated seed heads and large berries. Longer heads meant more berries, and large berries meant more endosperm in each seed. More endosperm meant more carbohydrates and higher alcohol yields when rye whiskey was being made using that variety. Egyptian/Mammoth White rye was known for its ability to make very flavorful, high quality whiskey. The seeds also contained a higher protein content, which translated into higher conversion capability in fermentations and helped to contribute more dynamic flavors in the whiskey- especially when flavor-extraction apparatuses like the chamber still were used.

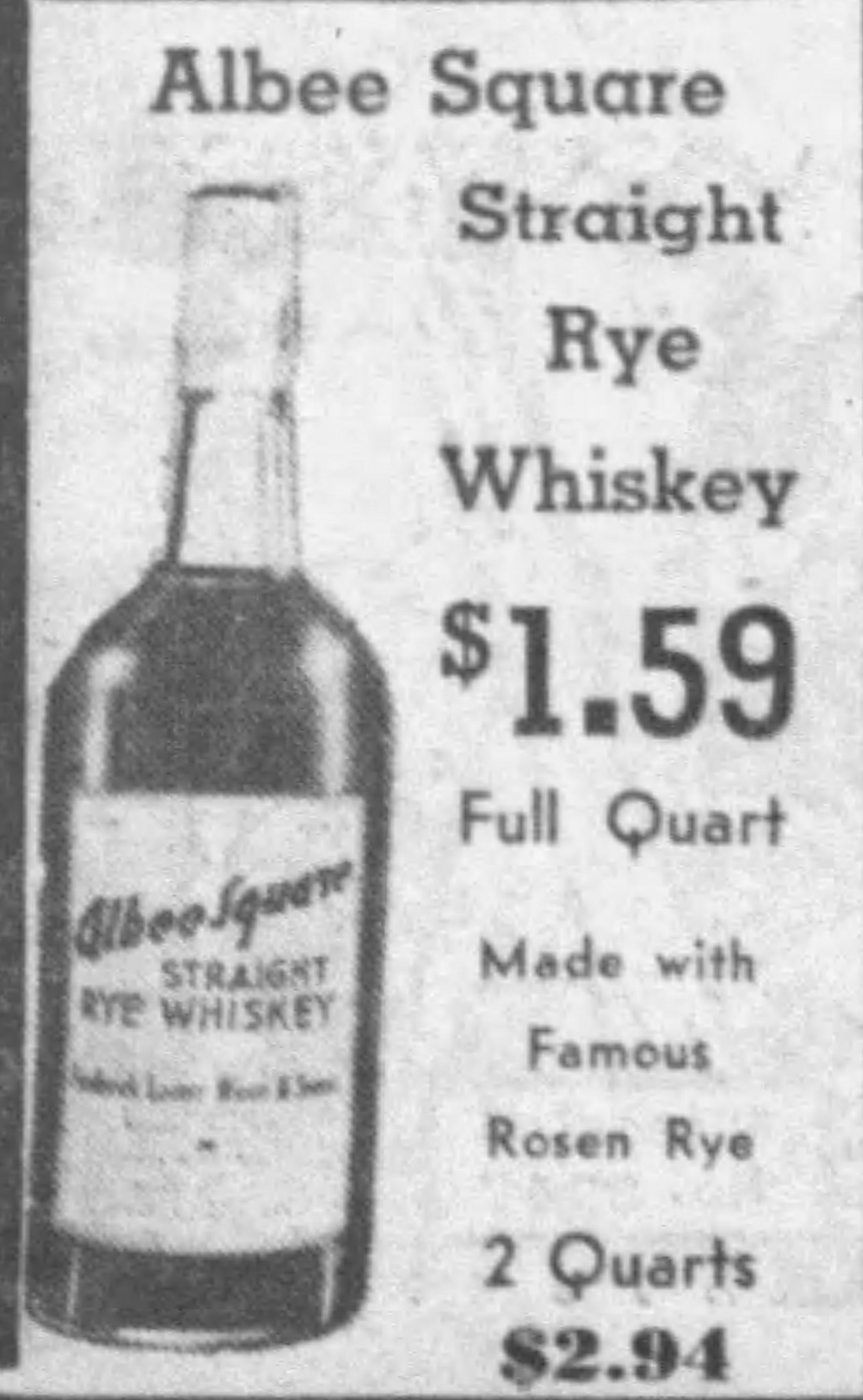

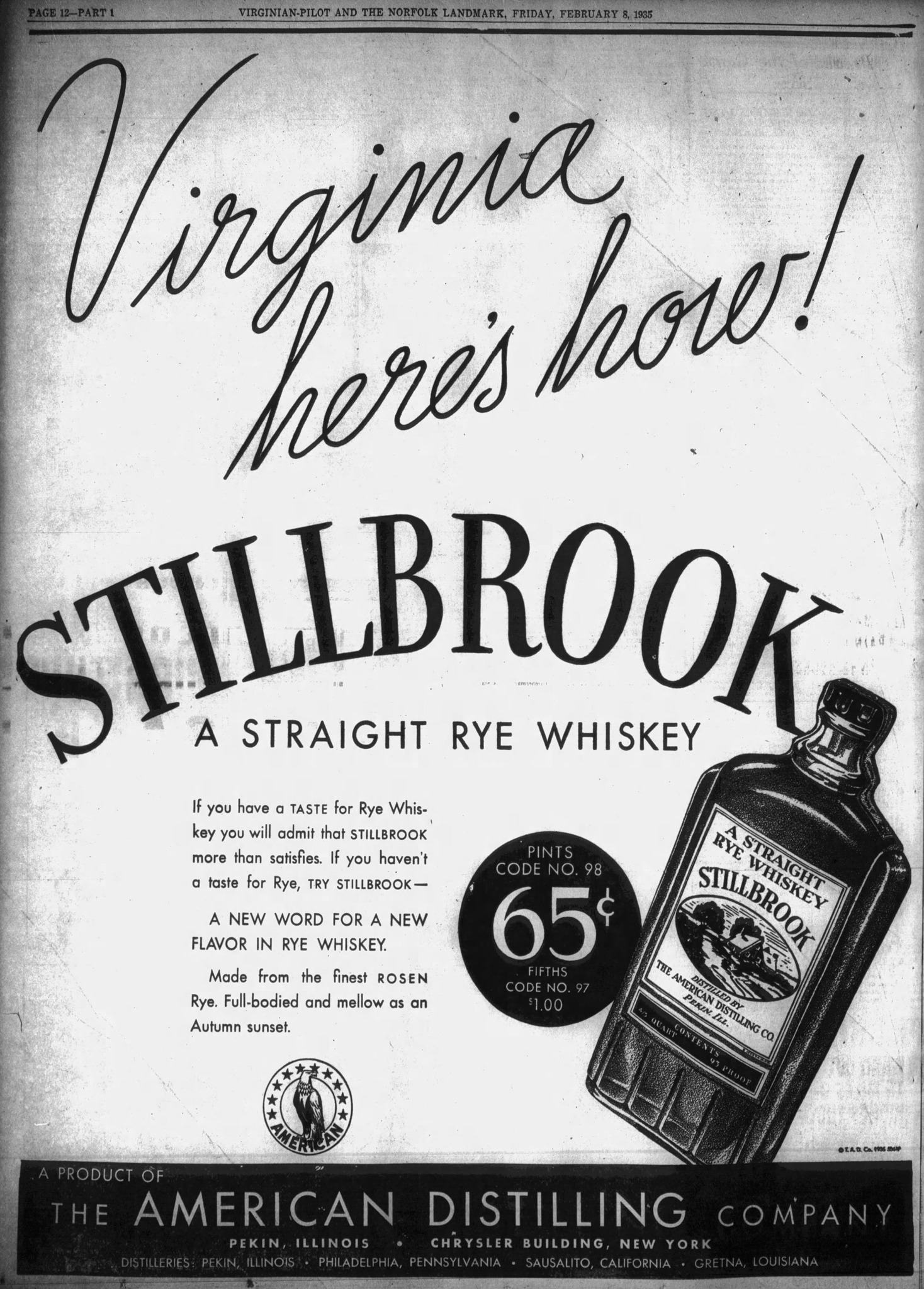

By the early 20th century, a new varietal of rye had been introduced to the U.S. grain market. Similar to what distillers had been using, Rosen rye was a white rye with a very competitive edge. Farmers in midwestern and Eastern states were thrilled with the performance of this new rye in their fields (higher yields), and distillers were thrilled with the impact it had on their whiskeys. Unfortunately for Rosen, the plant arrived in the United States just as the country was preparing to outlaw whiskey production. Prohibition had the added disadvantage of eliminating every rye farmer’s access to their best customers! After Repeal, with the encouragement of President Roosevelt, farmers were able to grow distilling and brewing grains once again- in great quantities. Rosen rye, which was still being grown in earnest throughout the 1920s, was readily embraced by some of the country’s largest whiskey producers- Hiram Walker and American Distilling Company among them. The expense of specialty grains like Rosen, however, increased as the market shifted toward commodity grains and toward corn-based spirits. As the number of rye whiskey distilleries decreased, rye grain began to lose its mojo.

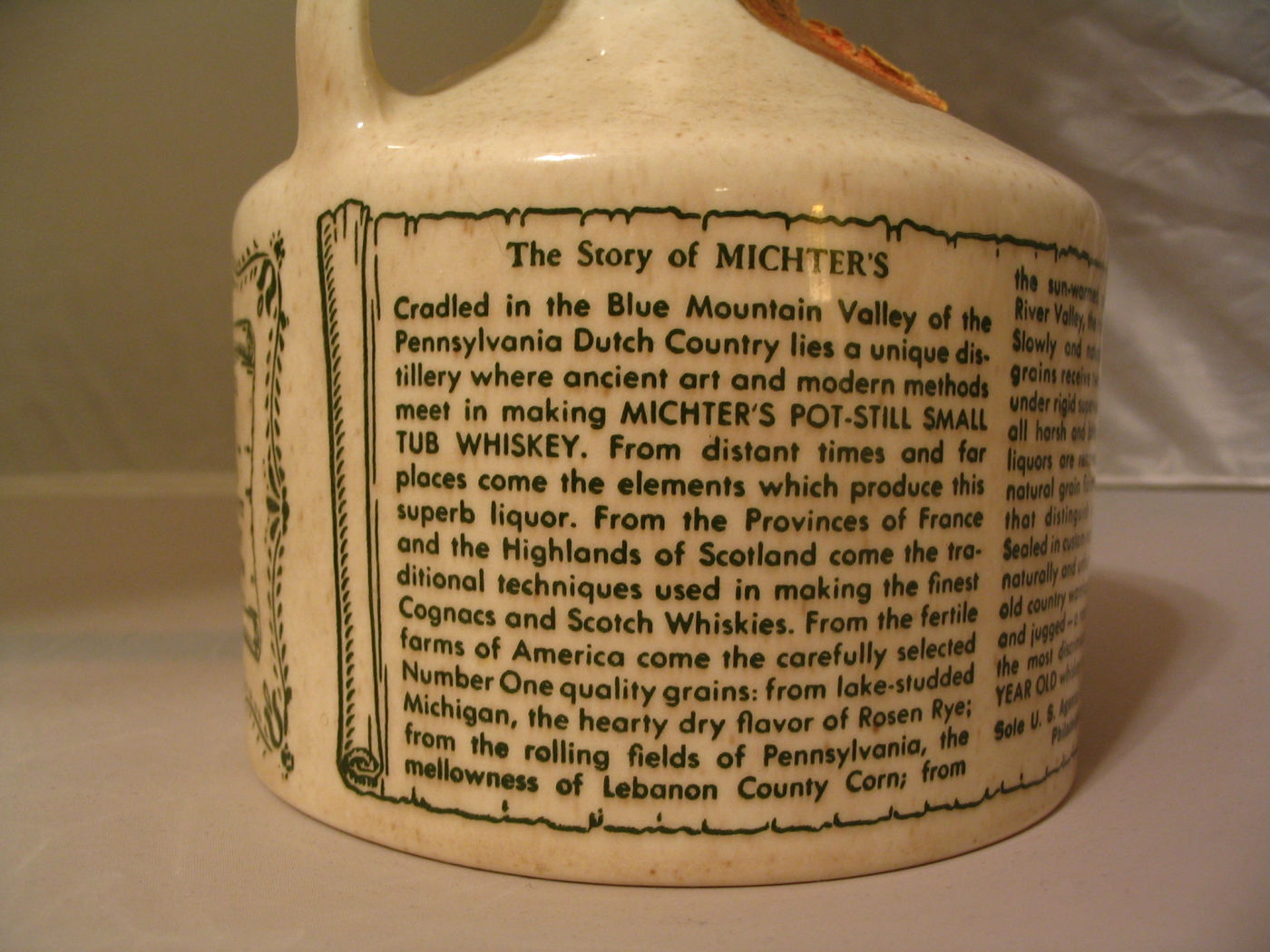

The 1950s ushered in a new era of grain supply consolidation. This was largely due to supply chain management regulations set in place decades before during Roosevelt’s New Deal. Distilling grains are all harvested around the same time, so every summer, the market floods and grain prices drop. Roosevelt wanted to extend the availability of commodity crops and make grain available year-round by establishing a grain reserve to more easily control the market. This had the unfortunate effect of placing the power in the hands of the largest farmers and the control of the market in the hands of the brokers. Rosen, which was prized by farmers for its yields in the field in the 1930s and 40s began to lose out to crops with much higher yields. The grain market was now dictating which grains distillers would use instead of the other way around. While there were rye whiskey distillers like Pennco Distillery (Michters) in Pennsylvania willing to pay more for local PA farmers to grow Rosen Rye for them into the 1970s, the bulk of whiskey being made in the United States was being made with corn, America’s favorite commodity crop. American whiskey would never be the same.

The amount of money being invested in rye research dried up by the 1970s and rye varietals that had been used for distilling purposes disappeared- literally! Egyptian white rye, the staple of American rye whiskey production in the 19th century, is gone. 100 years of rye production is M.I.A. (The varietal is literally missing. To this day, there is no record of Egyptian/Mammoth white rye seeds existing in seed banks because it was never sampled and saved for posterity’s sake.) Rosen rye, which HAD been sitting idly in isolated seed banks was returned to Pennsylvania by Penn State University with the financial support of he Delaware Valley Fields Foundation in 2015. Efforts are still underway to address the production of historically significant rye whiskeys in Pennsylvania. The return of heritage rye grain use in Pennsylvania rye whiskeys is a huge leap forward in recovering what’s been lost for so long.*

Very few rye whiskey-makers are using heritage rye grains- though admittedly, these are still early days in the heritage grain movement. Distillers usually chose to use non-variety stated rye or hybridized rye varietals for their rye whiskey mashes, though there are several good reasons for this: 1. It’s significantly less expensive to buy commodity rye grain. 2. Hybrid ryes provide more bushels per acre for farmers and produce a larger berry than most other ryes, which usually translates to higher alcohol yields for distillers. The trade off with hybridized ryes (like Brasetto), is that they were never bred with flavor in mind. Unfortunately, while agronomists were selecting and breeding plants to create higher-yielding hybrid ryes (more seeds per plant at harvest), they were sacrificing quality and flavor in pursuit of quantity. Most modern hybrid ryes were also bred for larger berry size, height uniformity for even pollen distribution, and overall crop consistency. This may be good news for modern flour mills or for livestock feed mills looking for rye with a higher carbohydrate content, but these grains were never going to be ideal for buyers prioritizing flavor in their rye- like distillers and bakers. (Read more about why rye whiskey fell out of favor here- http://www.dramdevotees.com/why-did-rye-not-survive…/)

There are certainly arguments for using NVS or hybrids ryes, but the proof is always in the whiskey. When tasting a heritage grain whiskey vs. a hybrid rye, there is no contest. The heritage rye is quite different and it’s easy to taste why those ryes were favored by distillers 100 years ago. The question for distillers is, “Is it worth the trade off to use a lesser rye?”

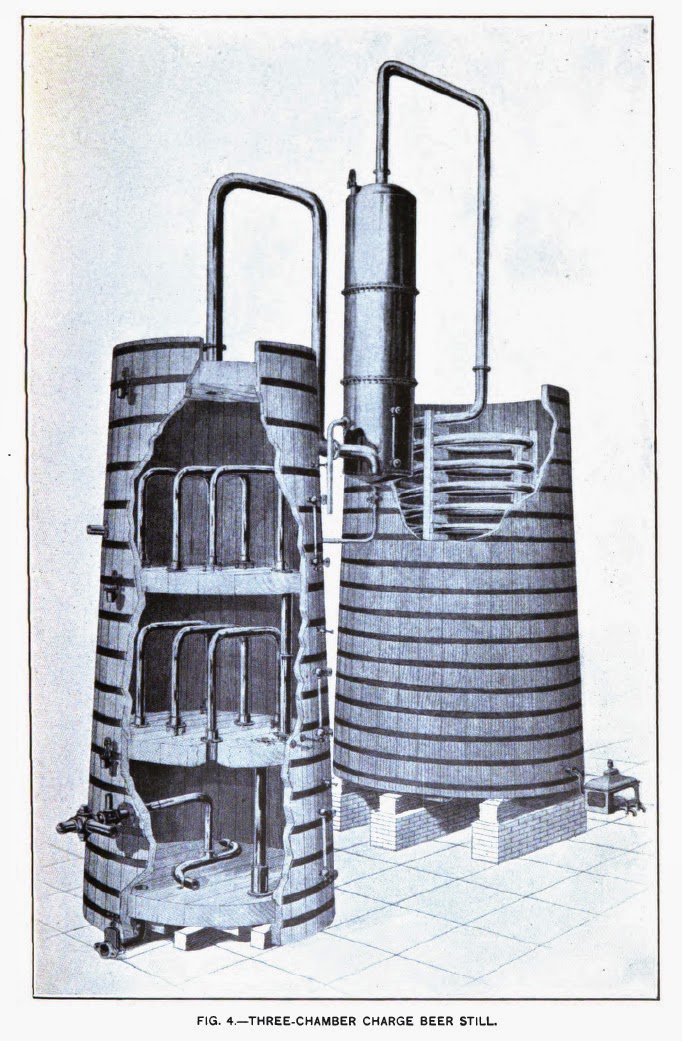

To be clear, Pennsylvania’s highly competitive pre-Prohibition rye whiskey distillers never traded convenience for quality. We can see this stubborn mindset through their insistence upon using inefficient chamber stills, open wooden fermenters, worm tubs, steam-heated warehouses Year round), and large quantities of high-quality rye in their mashbills. They could have abandoned tradition and cut costs and corners, but they never did. While one might argue that Pennsylvania’s rye makers were operating under flawed reasoning, but their success speaks for itself. In a crowded marketplace, Pennsylvania rye whiskey always represented the finest whiskey being made in the United States. When 90% of Kentucky’s distilleries sold out to the Whiskey Trust in the late 1890s, Pennsylvania’s millionaire distillers held out and refused to sell one distillery to the Trust. (Unfortunately, Prohibition would prove devastating to their independence.)

The modern whiskey industry exists in a highly competitive market, so is it in Pennsylvania’s interest to use higher quality grain? Is the extra cost worth it? I would certainly say that it is, but I can also understand why a distiller might start small and scale up slowly. The heritage grain market can grow alongside the distillers that choose to prioritize it- just like they did in the 19th century. Heritage grain rye whiskeys hold the potential to stand out in a crowded marketplace, just as they stood out over 100 years ago. Slow and steady wins the race, as they say. And if there’s one thing that distillers and farmers are good at, it’s being patient. Time will tell if consumers come around to embrace the complexity of rye whiskey…but I must ask, “How can 200 years of rye whiskey’s dominance in the American spirits market be wrong?” Those old distillers knew a thing about a thing or two. Perhaps its time to trust their wisdom.

*The first county to begin growing Rosen rye in earnest in Pennsylvania was Indiana County.