Where did “wheated bourbon” come from?

To be clear, “wheated bourbon” is a marketing term. The term has no historic precedent before the late 1990s. It is simply a modern means to describe bourbon made with wheat as the “flavoring grain” in place of rye, the more traditional grain used in bourbon production to balance the 70% (or more) corn used in a bourbon recipe. Distillers’ malt, made from barley, is used in smaller proportions (10% or less) than rye- specifically for its diastatic power to convert starches to sugars, not for its contribution to the flavor of bourbon. While distiller’s malt obviously contributes flavor to bourbon (It’s an ingredient!), it is specifically designed to prioritize conversion power over flavor contribution. After corn, rye is usually the small grain chosen to contribute the most dynamic flavor to a bourbon, so swapping out rye with wheat is clearly going to create a different flavor profile in the finished product. “Wheated bourbon” became a popular method of describing several products that were being manufactured by different bourbon distilleries in Kentucky in the early 2000s. That’s it…Sort of.

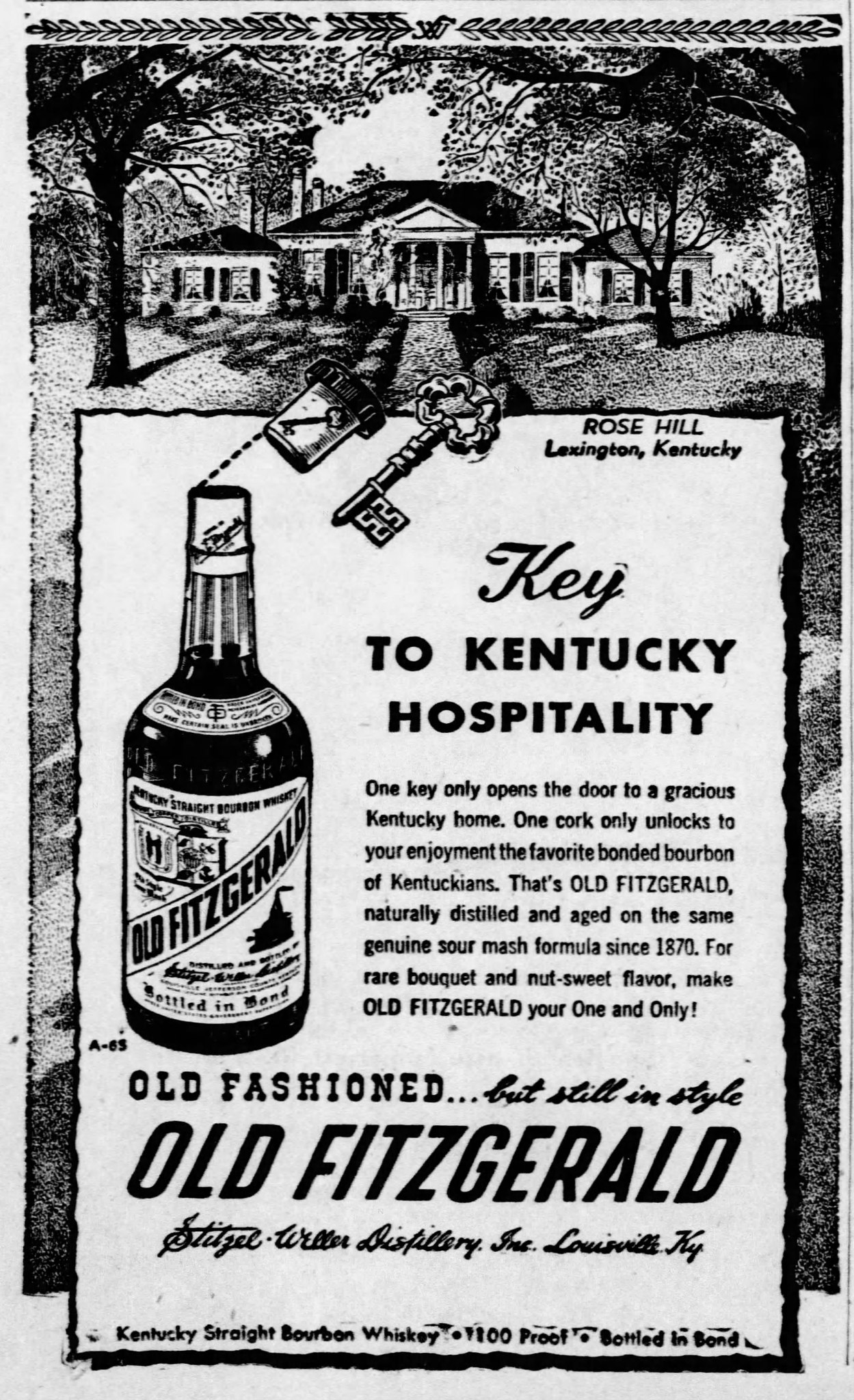

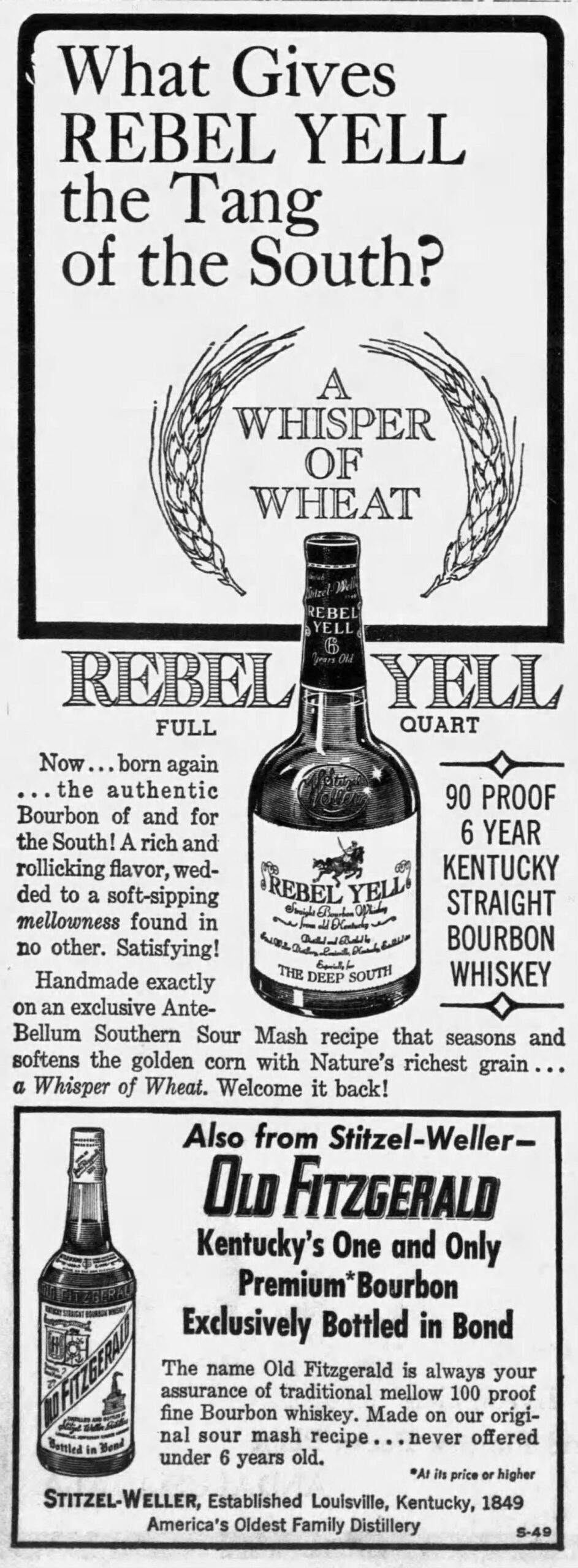

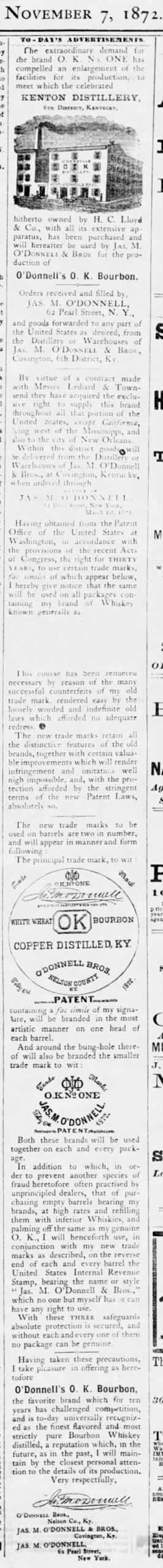

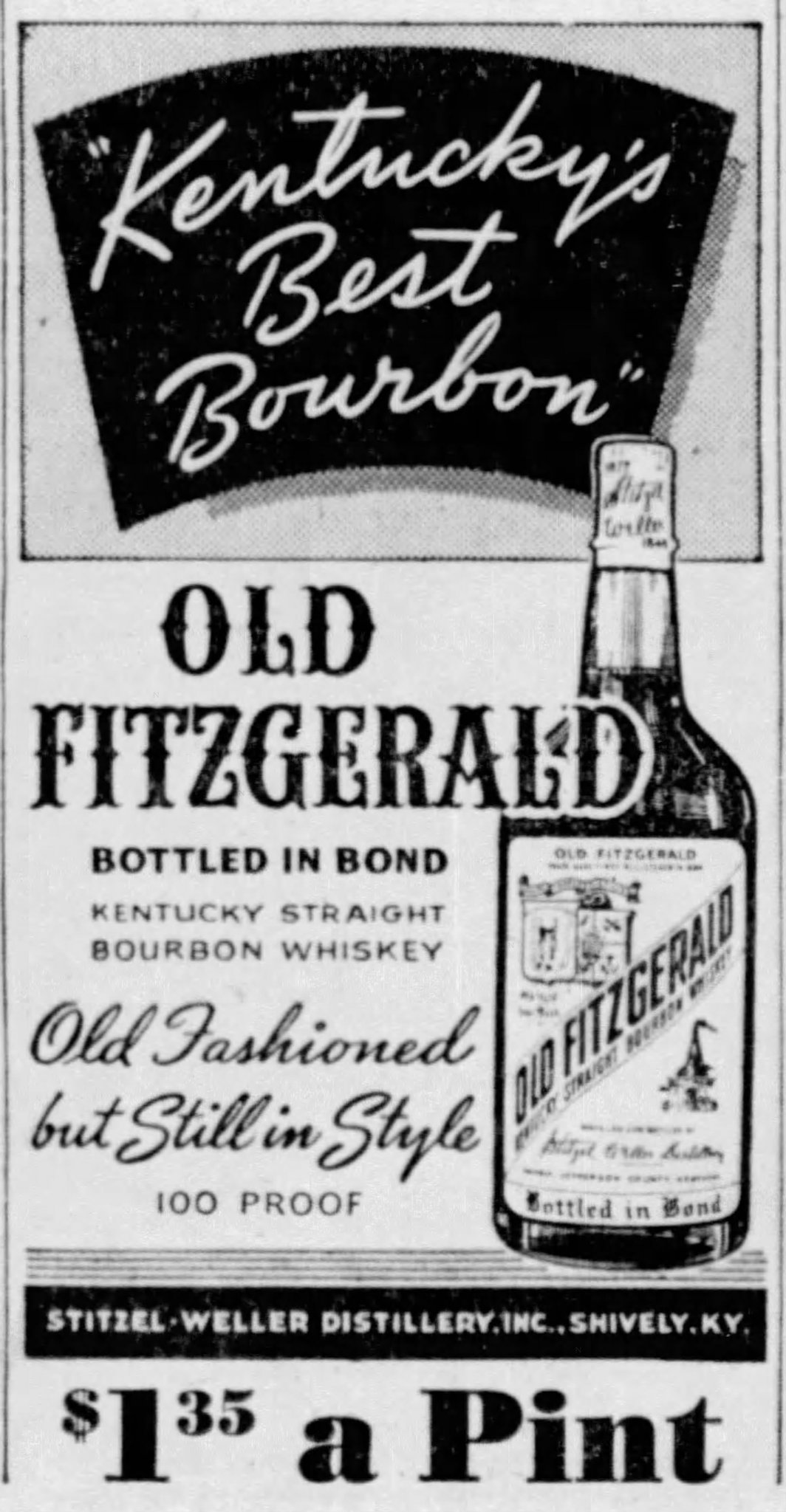

“Wheated bourbon” has always been a way for marketers to connect modern bourbon whiskeys to Stitzel-Weller. The Sazerac Company, which opened their Buffalo Trace Distillery (Frankfort, KY) in 1999, owned the W.L. Weller brand which was once manufactured by Stitzel-Weller in Shively, KY (once part of Louisville until 1938 when it became its own taxable district during the Great Depression…yes, because of whiskey). Heaven Hill Distillery (Bardstown, KY) owned the Old Fitzgerald brand, also considered a “wheated bourbon” and also previously manufactured at the Stitzel-Weller plant in Shively. (“Old Fitz” would become Larceny in 2012 to make room for older, higher priced specialty releases of Old Fitzgerald.) Same goes for brands like Rebel Yell, owned by David Sherman’s Luxco (St. Louis, MO), and Makers Mark, owned by Seagram’s (and then Allied-Domecq after 2001) but run by Bill Samuels, Jr. around the turn of the 21st century. Rebel Yell had been a Stitzel-Weller product, while Makers Mark was essentially using Stitzel Weller’s “wheated” recipe (and yeast!) at their distillery in Loretto, KY. I don’t think I need to explain that whiskey made at any distillery other than Stitzel-Weller would not be manufacturing a product in the 1990s or early 2000s that resembled anything once made at Stitzel-Weller. Some brands, like Sazerac’s Van Winkle line of whiskeys (and some of their antique collection whiskeys), DID contain whiskey that HAD been manufactured at Stitzel-Weller Distillery in Shively- whiskey that had been manufactured before the plant ceased operations in 1992. But those whiskey stocks ran dry around 2017, so the whiskey that made the brands famous to begin with have been gone for nearly a decade. As confusing as all this may sound, it’s not…not really. The act of buying a brand and making your own version of that brand at a different distillery has been a common practice since Prohibition. Companies like National Distillers and Schenley built their post-Prohibition brand portfolios on the backs of distillers and brand owners that were forced out of business in 1920. There was a lot of talk about heritage and tradition after Repeal, and while Kentucky’s distilling communities were certainly chock full of both, the big business of brand marketing was never going to be honest about the histories of these acquired brands. They couldn’t be! If they explained that their famous brand bore little to no resemblance to the whiskey that made those brands famous in the first place…well…that wouldn’t have gone over terribly well with consumers. Why build a new brand when you can piggyback on 50+ years of built-in brand loyalty? It was the marketing of these brands that has created so much confusion. Instead of inventing new names for these new products, they clung to the old brand names- because everyone knows that tradition sells whiskey. Again, this is nothing new and has been done for about 100 years, but consumers deserve some perspective.

There’s no denying that efforts have been made to make connections between modern “wheated bourbons” and the historically significant whiskeys made in Shively. Everyone from Buffalo Trace to Diageo has been blurring the lines between what “wheated bourbon” is and what it once was. Anyone that has tried Stitzel-Weller’s Rebel Yell or Old Fitzgerald from the 1960s, 70s, or 80s next to a modern “wheated bourbon” product knows that there is VERY LITTLE COMPARISON to be made. The truth is that a distillery as relatively small as Stitzel-Weller would never have been able to keep up with the demand generated by the modern bourbon boom- at least not in a way that would satisfy the needs of big business. One need only look to Scotland to see how difficult it would be to manufacture bourbon on the scale it’s being produced in the US. The Glenmorangie Distillery, in northern Scotland, might be described as a Prohibition-era-sized production facility. It manufactures about 4,700 gallons of whisky per day. At its peak, Stitzel-Weller manufactured between 18 and 19,000 gallons of whiskey per day. Today, Buffalo Trace manufactures about 120,000 gallons per day. That’s a bit staggering when you think about it, isn’t it? To be fair, a modern American bourbon distillery is more closely related to a Scottish grain distillery, so the closest comparison one might make would be to Cameronbridge Distillery (column stills), not Glenmorangie (pot stills). Cameronbridge Distillery manufactures about 98,000 gallons of whiskey per day. But Scotland is not famous for its grain distilleries, is it?! It’s famous for its single malt scotch distilleries, just as Kentucky was once famous for its many smaller scale production facilities…like Stitzel-Weller. Is it any wonder that “wheated bourbon” has changed so much as production has been steadily ramped up in the US?

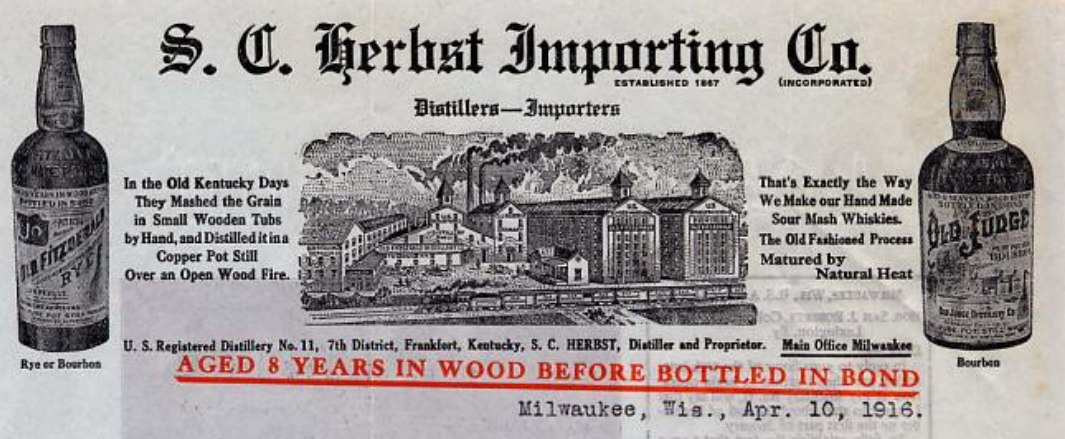

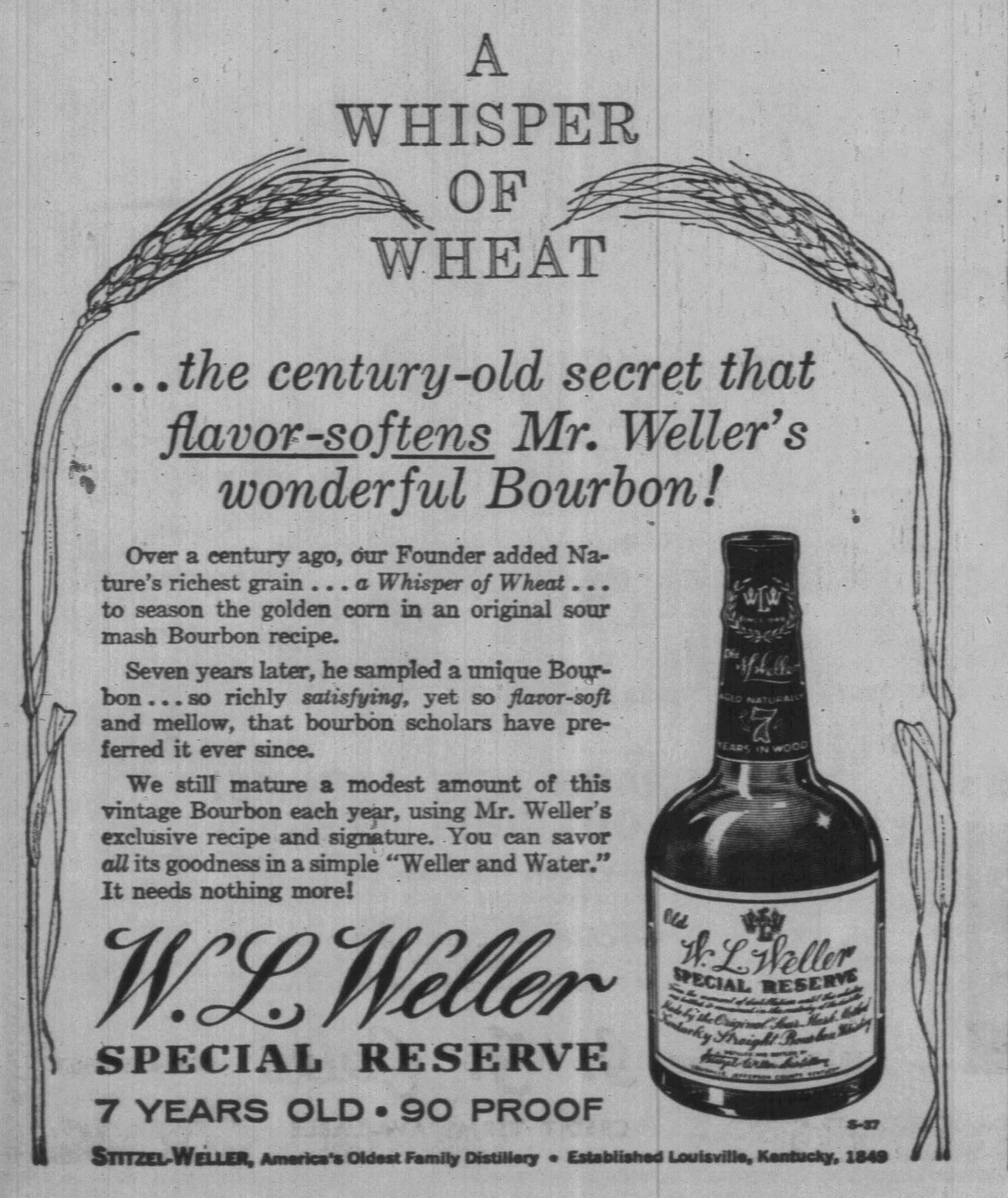

Stitzel-Weller was not without its own marketing campaigns before it closed in 1992. We’ve discussed how distilleries after Prohibition acquired brands, and Stitzel-Weller was no exception! Old Fitzgerald, their core product, was an acquired brand, too! Before Prohibition, the brand belonged to S.C. Herbst of Milwaukee, WI and had been manufactured at the Old Judge Distillery (RD #11) in Frankfort, KY. While Stitzel-Weller’s marketing team never used the words “wheated bourbon” in their ads for Old Fitzgerald, they used the description “a whisper of wheat”, which implied the same thing. The “whisper of wheat” description seemed to coincide with a new advertising campaign launched in 1962 for Stitzel Weller’s W.L. Weller bourbon (Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas) and its Rebel Yell Bourbon (Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee). Rebel Yell was the creation of Charles Farnsley, nephew of Alexander Thurman Farnsley, president of W.L. Weller & Co. and founder of Stitzel-Weller Co. The idea that wheat might be an marketing angle for post-Repeal advertisers of whiskey was born! Before “whisper of wheat”, the description “nut-sweet flavor” was used to describe Stitzel-Weller’s (SW) whiskeys. “Nut-sweet”, as odd as it may sound to a whiskey consumer today, seems to have carried over from other successful marketing campaigns of the early 20th century. Products like Kellogg’s breakfast cereals, breadstuffs (rolls and crackers), meat, and even tobacco products (cigars and cigarettes) were advertised as being “nut-sweet”! We can only assume that this description refers to the addition of wheat because there is no specific mention of any wheat being used at all. While modern marketing campaigns for “wheated bourbons” often draw comparisons to bourbons that had been manufactured at Stitzel-Weller as far back as 1935, there is little evidence to prove that wheat had always been incorporated into SW’s mashbill in the first place! I know…sounds crazy, right? But as I explained in my post yesterday, I’m looking for facts, not marketing lore…and there are plenty of clues to suggest that wheat may not have been introduced to the mashbill at Stitzel-Weller until the 1940s!

Stay with me! I’m not discounting the possibility that wheat had been part of the Stitzel-Weller mashbill since they rolled their first barrel of bourbon rolled into their warehouse…but I have questions…and like I said yesterday, “What began as a search into where wheated bourbon came from has opened a pandora’s box of obscure information, most of which has been whitewashed by marketing lore.”

Stitzel-Weller: Origins of the Wheated Mashbill

Stitzel-Weller is certainly responsible for popularizing the use of wheat in bourbon mashbills. But let’s be clear about something. Wheat whiskey and the use of wheat in bourbon- or for any whiskey for that matter- was not unique to Stitzel-Weller. Pure wheat whiskey, as a style of American whiskey, is much older than bourbon. Wheat whiskey was very commonly used by liquor firms with rectifying licenses, either bottled in its straight/pure form or in blends. Pure wheat whiskey was manufactured for bulk sale by BOTH rye and bourbon distilleries. Distilleries diversified their outputs for the same reason any business would sell more than one product. It was financially in their interest to do so. Historically, the use of wheat in whiskey was dependent upon its price and availability, or sometimes, upon the legal limitations placed upon its use. Plentiful harvest years usually brought down the cost of wheat, making the grain more available for use by distillers. During wartime, the US government often curtailed the use of wheat by distillers, prioritizing its use by mills (flour) or bakeries (bread). Stitzel-Weller did not begin distilling any bourbon until it opened in 1935, so it’s difficult to know when the decision was made to incorporate wheat into their bourbon mashbill.

It’s worth noting that the whiskey manufactured by Stitzel-Weller in Shively was not available for sale until 1937, and that their initial brand was an 18-month-old straight bourbon called “Kentucky Oaks.” (Yes, this was bottled during that strange window of time where an 18-month-old whiskey could legally be labeled as “straight whiskey.”) Anything older than a 4 or 5-year-old bottled-in-bond whiskey labeled as a Stitzel-Weller product during the 1930s (Prohibition-era medicinal whiskeys) was NOT manufactured in Shively. They were simply bottled by Stitzel-Weller from any number of barrels that had been stored in A. Ph. Stitzel’s concentration warehouse. Some of their Prohibition-era whiskey was labeled as having been bottled by W.L.Weller & Sons or A.Ph. Stitzel & Co. or Waterfill & Frazier as well, but they were all related companies. When we look at early bottlings (1930s) of Old Fitzgerald or W.L. Weller bourbons being sold by Stitzel-Weller, we can reference the back labels or tax strips of those bottles and see for ourselves that they had been manufactured elsewhere by other distillers. Weird, right? Meanwhile, the still house in Shively was busy cranking out distillate and laying down thousands of barrels in their warehouses. The first bottled-in-bond (4-year-old) Old Fitzgerald bourbons made in Shively would not be available until 1939. 6- and 8-year whiskeys distilled by Stitzel-Weller would not be available for sale until the 1940s.

So, when Stitzel Weller did have properly aged whiskeys available for sale, can we assume that those whiskeys were “wheated” bourbons? Herein lies the difficulty, right?

Old Fitzgerald had not been a wheated bourbon before Prohibition. It had been manufactured at the Old Judge Distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky, and there’s no reason to believe that Jerry Bixler, the distiller at Old Judge before Prohibition, had been using wheat in the manufacture of his version of Old Fitzgerald. (I will have to return to Mr. Bixler and his son, Claude Vernon Bixler (distiller for Labrot & Graham), in the future.) Then where did the wheat come in? My theory (though it is JUST a theory and may be heavily contested) is that wheat was introduced to the mashbill at Stitzel-Weller in the early 1940s while the company was ramping up production.

Between 1942 and 1946, the US government actively encouraged the use of wheat by distillers. There were several newspaper editors (see an example below) that complained about the use of wheat by distillers during the mid-1940s. They argued that the government was mishandling the surplus of wheat they found themselves having to store during the Second World War. But, who better to handle a wheat surplus than America’s distilleries? Historically, distilleries had always made use of inexpensive grain, but this wheat was FREE! Yes, that’s right! The surplus of wheat was given to Kentucky distilleries FOR FREE. I imagine that Kentucky’s distilleries made use of this wheat in many ways, especially for industrial use during the war, but I also imagine that creative distillery owners would have looked to their experienced distilling staff to make the best of the situation, as well. “Distilling holidays” during the war allowed distilleries to manufacture straight whiskeys for their own use. How interesting would it be if Stitzel-Weller’s master distiller, William H. McGill, made use of that excess wheat in a productive, delicious way?

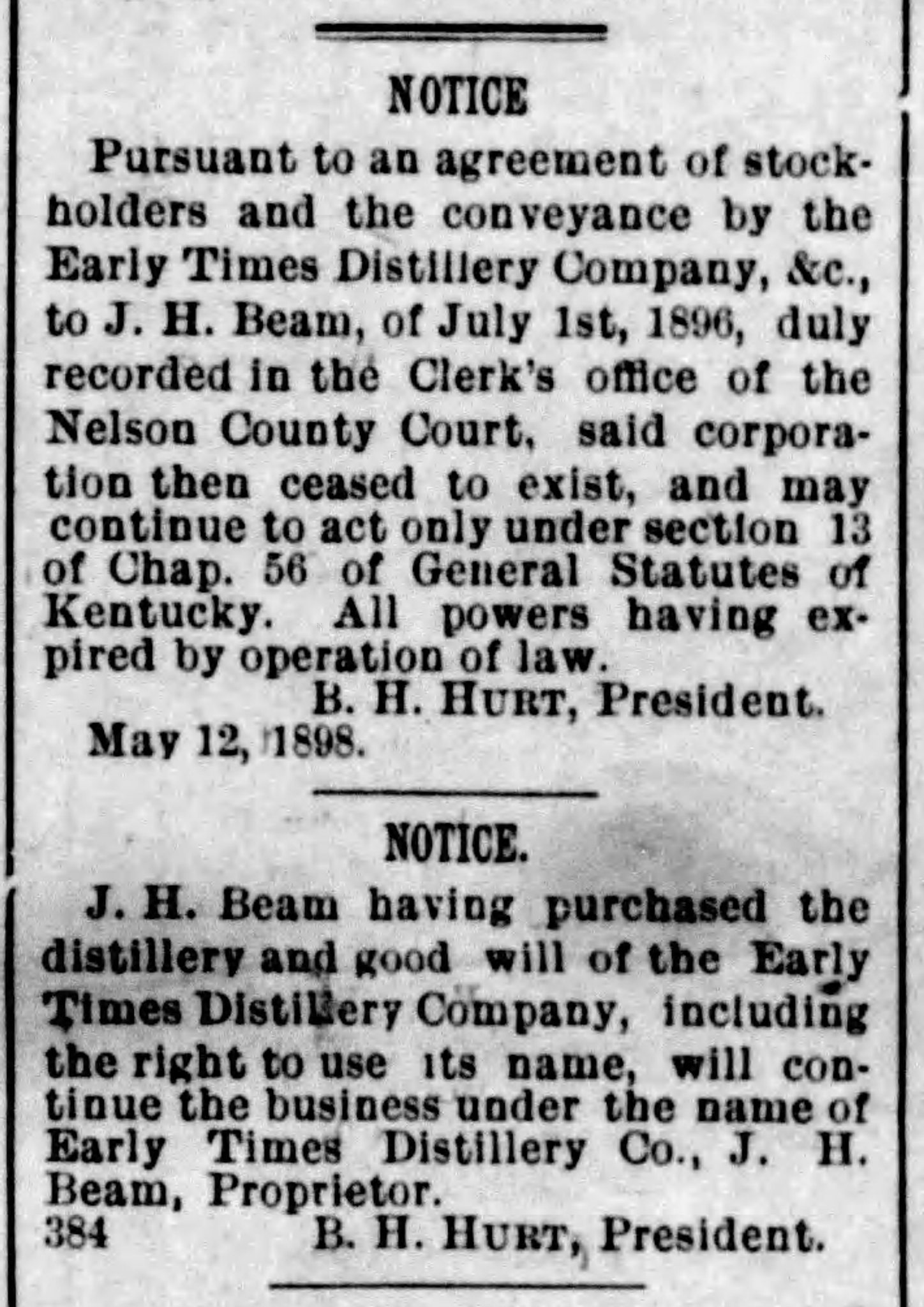

We must stop here to explain a bit about Will McGill, master distiller at Stitzel-Weller since 1935. While he had not been directly associated with the Stitzel or the Weller families before Prohibition…he HAD been associated with them INdirectly through his distillery in Bardstown. William H. McGill took a position as distiller at the Felix G. Walker Distillery in 1897, 5 years after Joseph Lloyd Beam married his younger sister, Katherine Leone McGill. Even if you’re unfamiliar with Kentucky distilling legend, Joseph Lloyd Beam, you’ve certainly heard of his slightly older (by 4 years) cousin, James Beauregard Beam, aka “Jim Beam”. Joseph L. Beam’s younger brother, John H. Beam, established the Early Times Distillery in eastern Bardstown in 1866. Joseph’s seven sons (Will McGill’s nephews) were the men behind much of the whiskey that was being made in Kentucky after Prohibition. While McGill’s family had been connected to the cooperage/distilling trade (son of James Meveral McGill), it was his association with Joseph and the Beam family that put him in the stillhouse making whiskey and mastering the art of yeast propagation. The brothers-in-law would eventually become partners. Will McGill’s partnership with Joseph L. Beam at the Felix G. Walker Distillery before Prohibition was a pretty big deal! In 1900, Hillmar & Ehrmann Co. bought half interest in the F.G. Walker Distillery, and by 1905, they owned it outright. Remember Hilmar & Ehrmann from my entry on Stitzel’s Story Ave distillery? Arthur Philip Stitzel had been a partner of the firm between 1901 and 1902, so here’s where we start to see the crossover between Stitzel, Beam, and McGill. Ownership is one thing, though. Distilling knowledge and experience is something else entirely.

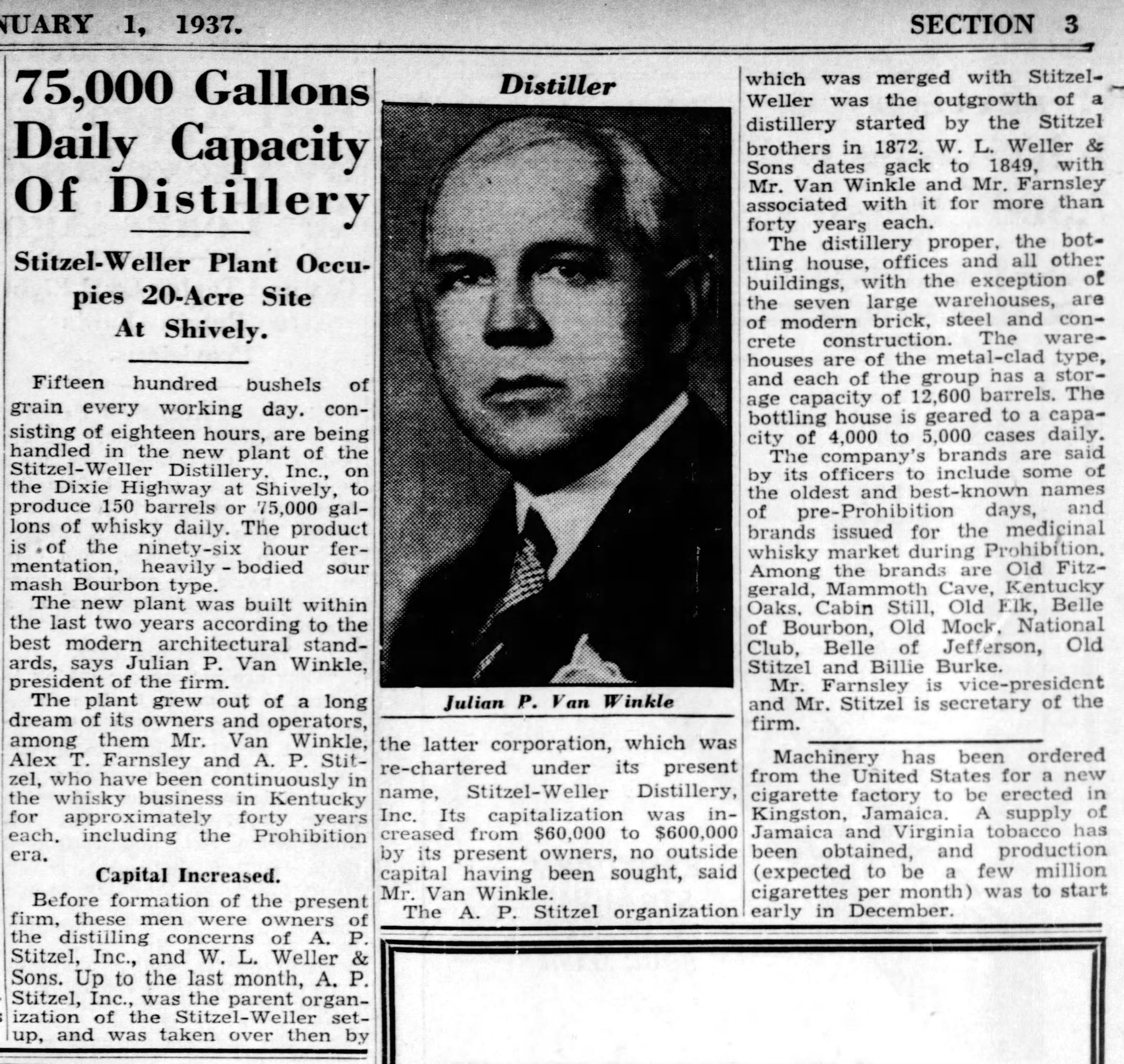

When Will McGill was hired by A.T. Farsley, J.P. Van Winkle, and A. Ph. Stitzel to act as master distiller at Stitzel-Weller in 1935, he was bringing his pre-Prohibition skillsets with him- skillsets handed down to him through Mr. Joseph L. Beam. Did Mr. McGill use his understanding of wheat-flavored mashbills right away in 1935, or did he use them in the early 1940s when wheat was offered for free by the government? Did the owners at Stitzel-Weller recognize that the whiskey being made with wheat was somehow superior to the rye-flavored whiskeys they had been making? Did they recognize that this “wheated” mashbill offered something more marketable for the company? It seems strange to me that a relatively new distillery would focus on a unique mashbill without the strong belief that it would eventually pay off. With a salesman like Julian Procter Van Winkle to promote the whiskey and a highly influential company president like Arthur Philip Stitzel, perhaps Will McGill’s whiskey would not have found its market…but as it happens, their “wheated” mashbill DID find success. Van Winkle, often touted as the “distiller” at Stitzel-Weller, was, indeed, an excellent salesman. Stitzel-Weller’s wheat-flavored whiskeys were recognized for their unique characteristics and sold well. By the 1950s, when the Star Hill Farms Distillery in Loretto was looking for inspiration for their Makers Mark brand, Julian P. Van Winkle was able to share Stitzel-Weller’s success by offering their “wheated” bourbon recipe to Bill Samuels. Roy Hawes, who had been working under Will McGill at Stitzel Weller since 1936, is quoted in an interview as being the one who personally delivered the yeast strain they had been using at Stitzel-Weller to Bill Samuels (owner) and Sam Cecil (distiller) in the 1950s.* Stitzel-Weller’s “nut-sweet” recipe had found a market, but perhaps they hadn’t anticipated how successful Mr. Samuels would be with his new product launch. Star Hill Farms and Stitzel Weller were the only distilleries to use that wheated mashbill for decades.

When Will McGill was hired by A.T. Farsley, J.P. Van Winkle, and A. Ph. Stitzel to act as master distiller at Stitzel-Weller in 1935, he was bringing his pre-Prohibition skillsets with him- skillsets handed down to him through Mr. Joseph L. Beam. Did Mr. McGill use his understanding of wheat-flavored mashbills right away in 1935, or did he use them in the early 1940s when wheat was offered for free by the government? Did the owners at Stitzel-Weller recognize that the whiskey being made with wheat was somehow superior to the rye-flavored whiskeys they had been making? Did they recognize that this “wheated” mashbill offered something more marketable for the company? It seems strange to me that a relatively new distillery would focus on a unique mashbill without the strong belief that it would eventually pay off. With a salesman like Julian Procter Van Winkle to promote the whiskey and a highly influential company president like Arthur Philip Stitzel, perhaps Will McGill’s whiskey would not have found its market…but as it happens, their “wheated” mashbill DID find success. Van Winkle, often touted as the “distiller” at Stitzel-Weller, was, indeed, an excellent salesman. Stitzel-Weller’s wheat-flavored whiskeys were recognized for their unique characteristics and sold well. By the 1950s, when the Star Hill Farms Distillery in Loretto was looking for inspiration for their Makers Mark brand, Julian P. Van Winkle was able to share Stitzel-Weller’s success by offering their “wheated” bourbon recipe to Bill Samuels. Roy Hawes, who had been working under Will McGill at Stitzel Weller since 1936, is quoted in an interview as being the one who personally delivered the yeast strain they had been using at Stitzel-Weller to Bill Samuels (owner) and Sam Cecil (distiller) in the 1950s.* Stitzel-Weller’s “nut-sweet” recipe had found a market, but perhaps they hadn’t anticipated how successful Mr. Samuels would be with his new product launch. Star Hill Farms and Stitzel Weller were the only distilleries to use that wheated mashbill for decades.

Does this prove anything? Not really. But it might offer some insight into why wheat may have been introduced into a classic rye-forward bourbon mashbill. Historically speaking, mashbills had never been considered very important where marketing was concerned. The introduction of regulations on American whiskey’s standards of identity in 1935 certainly would have had an influence. Suddenly, whiskey was supposed to be made a certain way with clear limitations placed on grain usage. The fact that Stitzel-Weller and Makers Mark were making whiskeys that separated themselves from “the crowd” was certainly impactful…even if it took years to establish that were, indeed, different. Charles Farsley certainly recognized the uniqueness of Stitzel-Weller’s wheated mashbill when he launched his campaign for Rebel Yell in the early 1960s. By the 1970s, “a whisper of wheat” had become a marketing angle for advertisers. It’s very hard to hard say with any certainty what drove the introduction of wheat into bourbon mashbills, but it’s easier to pinpoint when wheat became a marketable addition to bourbon. What we can say with certainty is that Will McGill and Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle helped to make that happen.

*It is also curious to note that Roy Hawes explained in that same interview that he had been sent from the Frankfort Distillery to run the stills at the Story Avenue plant in 1933. He described their use of 22-gallon (quarter cask) barrels to help rush product to market. He also mentioned the use of wheat grits during the war in the early 1940s.