Part 1.

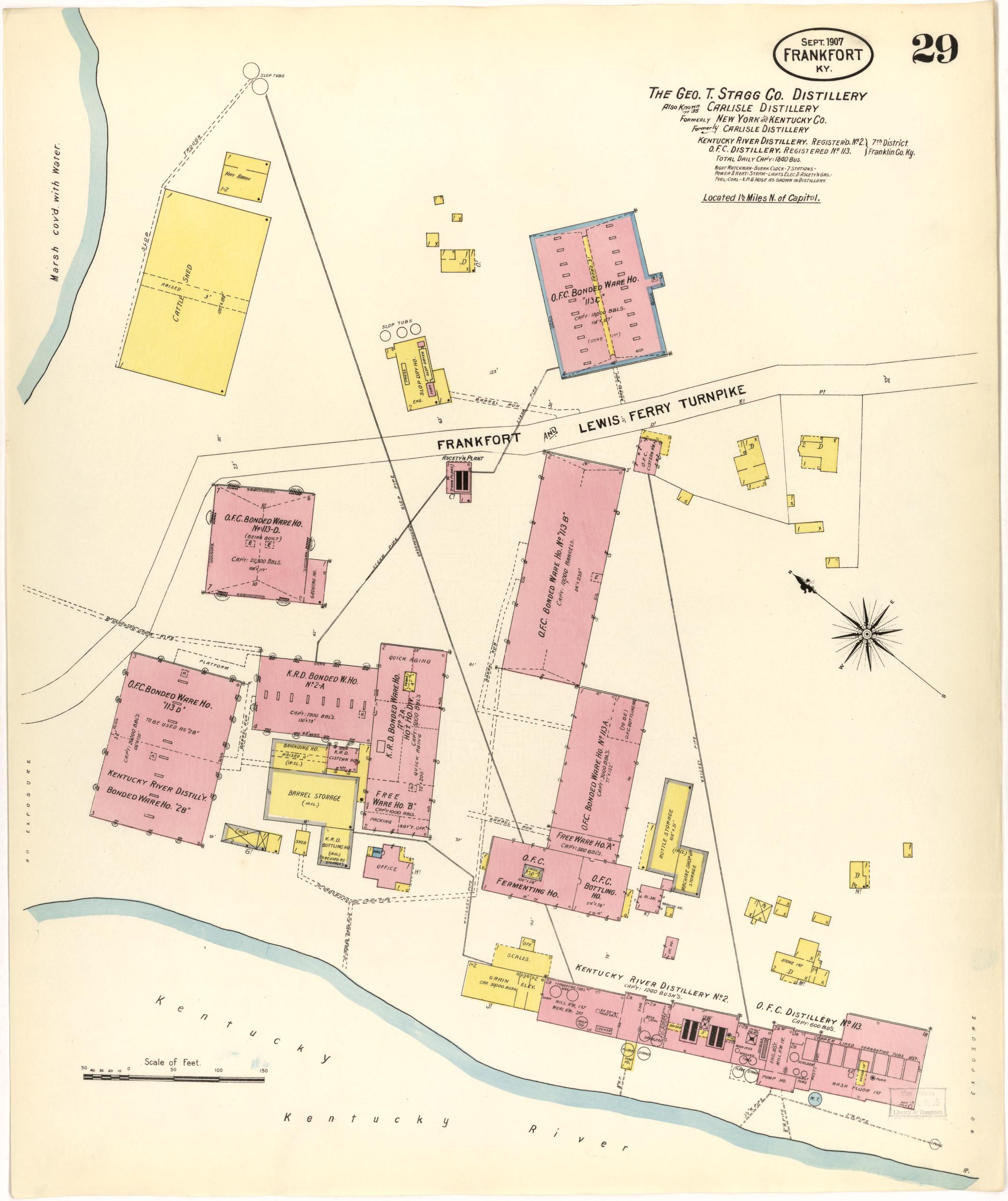

I have always wanted to know more about the man behind the marketing myth. George T. Stagg’s name has had quite an impact on the bourbon industry- and not at all because of any brand(s) bottled by Buffalo Trace Distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky. The “George T. Stagg” brand of bourbon did not exist until 2002, but the Stagg name has survived and endured for generations- against all odds. George T. Stagg was NOT from Frankfort, Kentucky, though he did own the two distilleries that once stood where Buffalo Trace’s distillery sits today. Stagg died in 1893, yet his name and the distilleries he touched while he lived have gone down in history. I want to look at the real man behind the brands we’ve come to know so well- a man who built his fortune in Missouri, not in Kentucky.

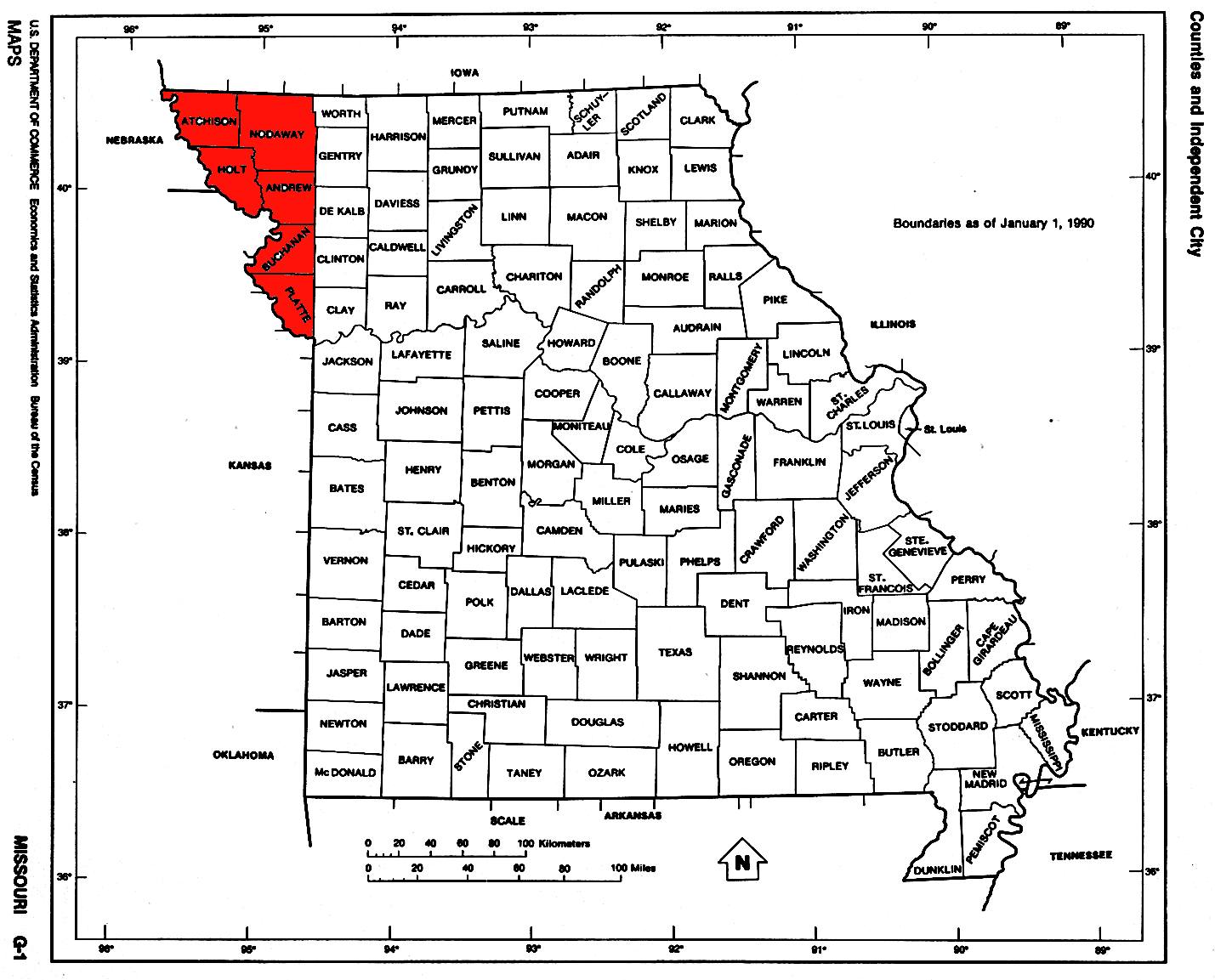

George Thomas Stagg was born on December 19, 1835 in Garrard County, Kentucky to Samuel and Margaret “Nancy” (Goodknight) Stagg. When George was a boy, his family relocated to Weston, Missouri in Platte County. The town of Weston, founded in 1837, was the first established settlement on the Platte Purchase- over 3000 square miles of territory in the northwest corner of Missouri that had been acquired from native people living there in 1836. Weston quickly became the 2nd largest port along the Missouri River (after St. Louis) and served as a stopping point for settlers moving further west. The 1850 census shows George (14) living with his father, Samuel Stagg (45-yrs-old), his mother, Nancy (43), and his older brother, Daniel (22). The Stagg family was living next door to Francis M. Bell (22 years), Elizabeth Bell (19 years), and their 1-year-old son, William, who had been born in Missouri. It seems likely that Elizabeth Bell was Samuel Stagg’s daughter (George’s older sister). The Bells had also moved from Kentucky to Missouri.

While most of George Stagg’s formative years had been spent in Missouri, the sudden loss of his mother when he was 14 (1849) and his father just 3 years later (1852) likely forced him to find his own way in the world- and to find his own fortune. The family seemed to maintain their connection to Kentucky, because in 1858, when George was 22, he returned to Madison County to marry Eliza Bell “Bettie” Doolin. In fact, George seemed to be making trips back and forth between Kentucky and Missouri throughout the latter 1850s. His young wife had become pregnant shortly after their marriage, and she remained in Kentucky with her family. The trade route between the two states was not an easy one; It likely hardened him for river travel and instilled in him a great deal of practical experience in the business of trade.

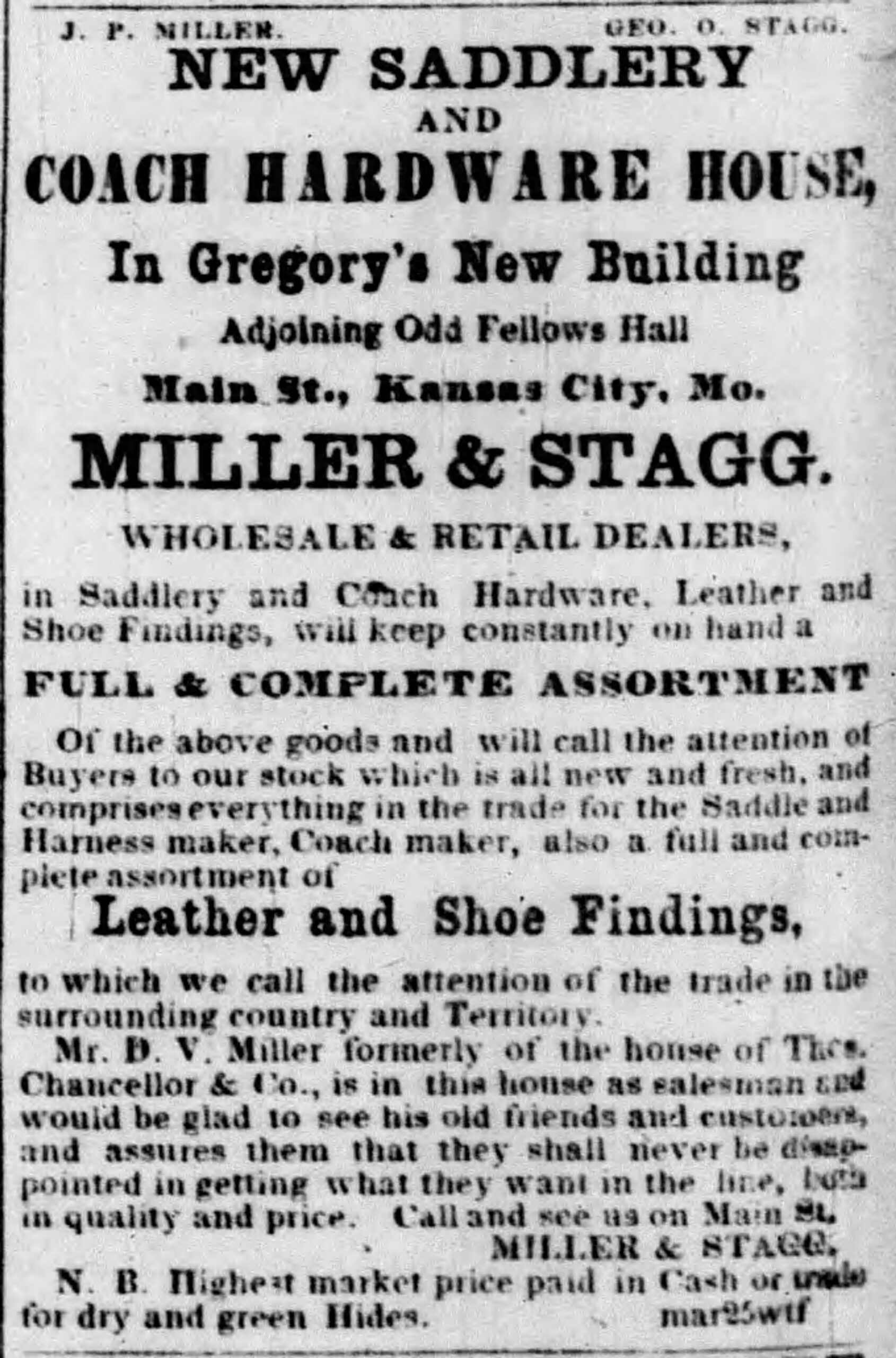

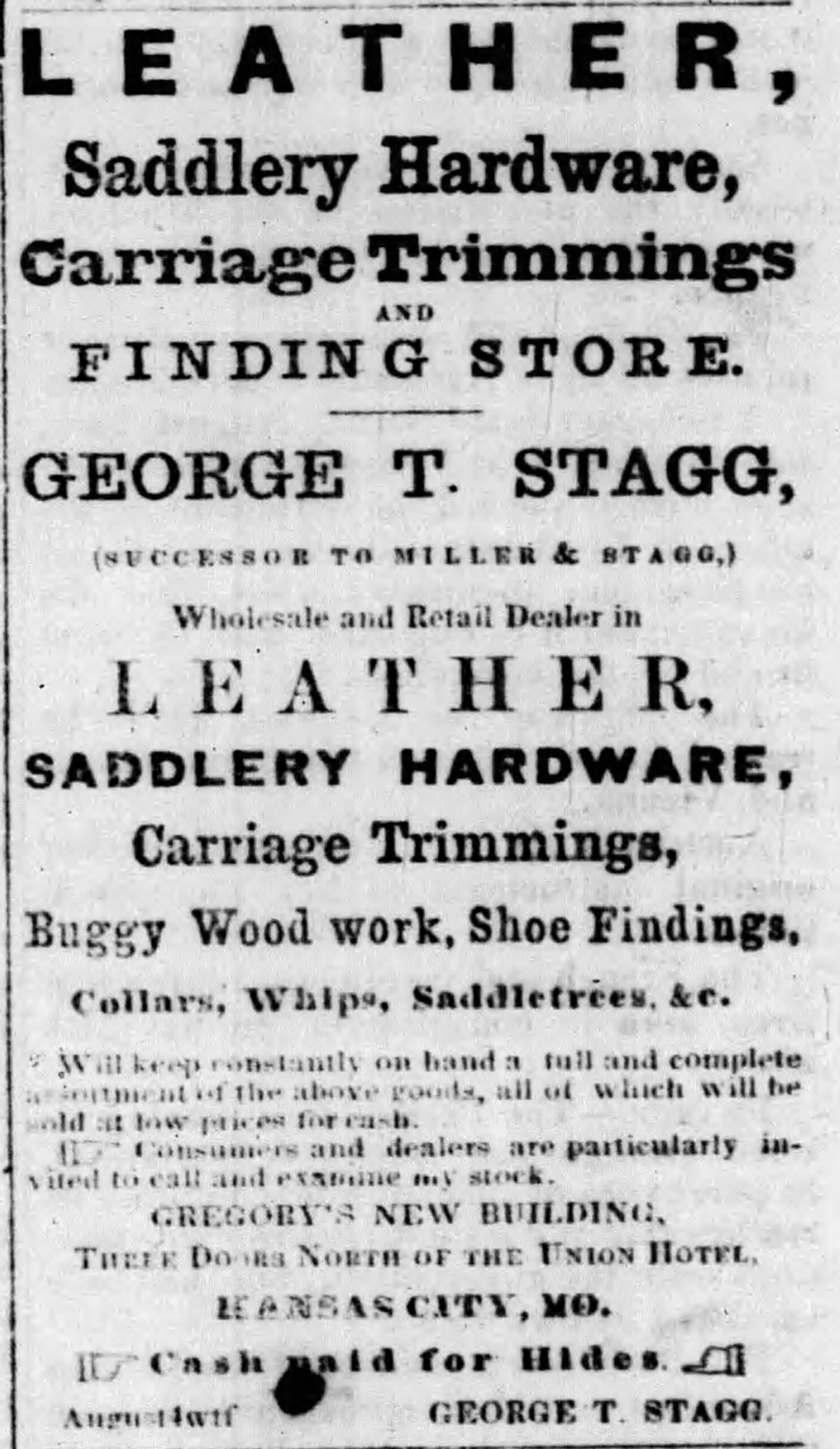

Newspaper advertisements placed in Kansas and Missouri during the summer of 1859 show George T. Stagg partnered with J.P. Miller as “Miller & Stagg.” The men were acting as wholesale & retail dealers in saddlery, coach hardware, and shoe fittings in Kansas City, Missouri- an ambitious business for a town catering to travelers going west on horseback and by wagon. Miller & Stagg were doing business out of the “new Gregory building” on Main Street, “3 doors north of the Union Hotel”. (Mr. William S. Gregory had been the first mayor of Kansas City, and he and his brother, James A. Gregory, had been running a general merchandise business in town since 1853.) On June 8, 1859, George and his wife welcomed their first child, Charles M. Stagg. By November 1859, George was selling off his saddlery and retail stock to a man named W.J. Dillon and moving back to Kentucky. His 6-month-old son, Charles, died shortly thereafter- on December 28.

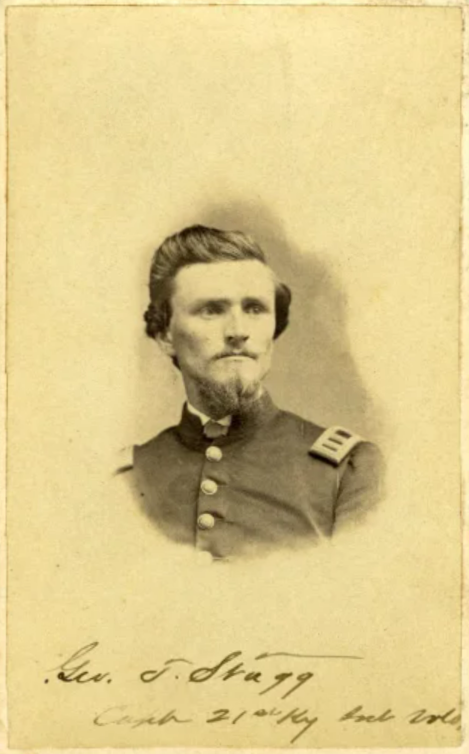

The 1860 census shows George working as a clerk in a shoe store, but the census also reveals that he and his wife were living as boarders with both of their ages listed incorrectly. The shoe business would not have been foreign to him. In fact, it was probably connected in some way to the leather goods business he had been conducting back in Kansas City. The early 1860s, however, would prove difficult for the Stagg family. The country was on the cusp of Civil War, and George was preparing to set aside his career for 3 years in the military. George and Bettie’s second child, Lida Bell Stagg, arrived just as the nation (and her father) went off to war.

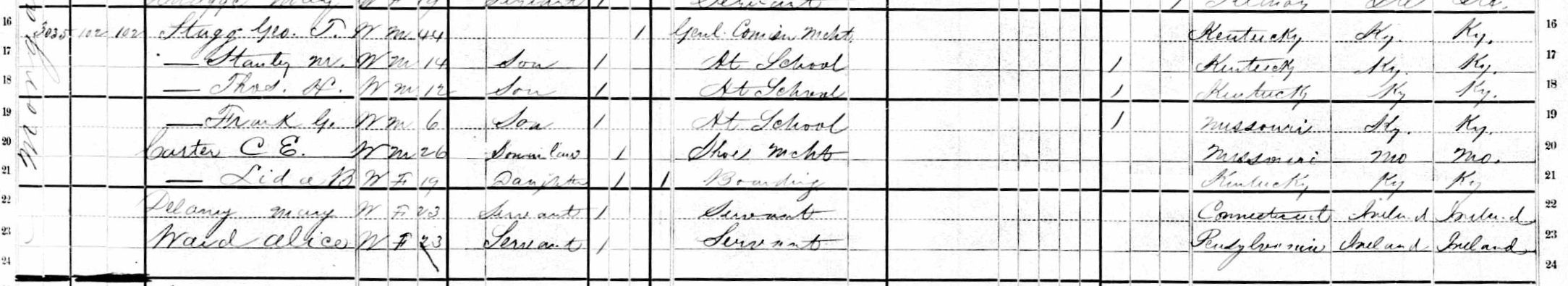

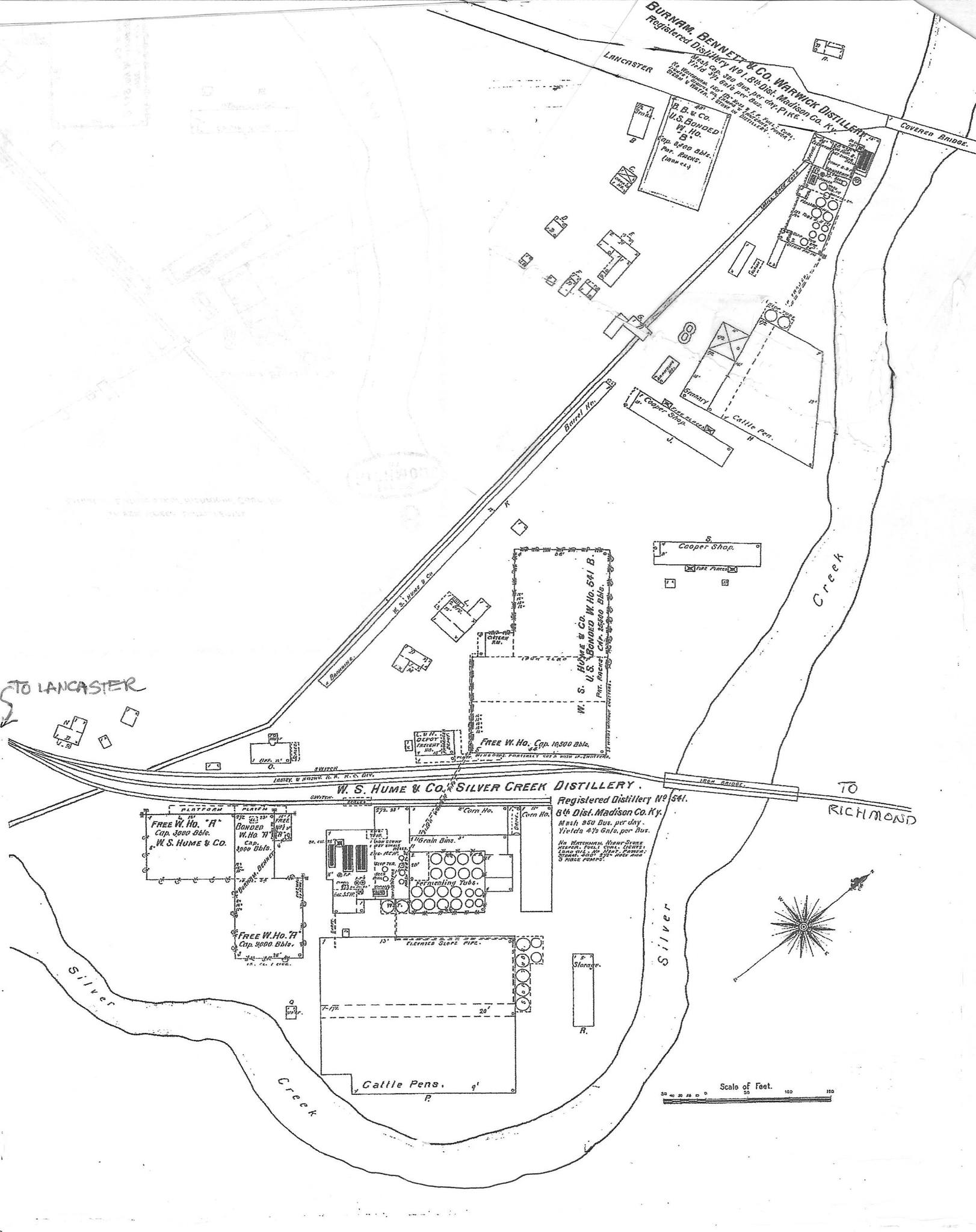

George enlisted to serve the Union Army on November 2, 1861. He was assigned the role of First Lieutenant in Kentucky’s 21st Infantry. By January 4, 1863, Stagg had been promoted to Captain. After over three years of service, George was mustered out on January 4, 1865, 3 months before the war finally came to an end. The Stagg family continued to grow with the arrival of Stanley Matthew in 1864 and Thomas Hiram in 1868. It appears that during these years, George had begun to work as a distiller in Richmond. (1870 US Census lists 34-year-old Stagg as a “Distiller” living in Richmond.) The major distilleries near Richmond in 1870 were known as the Silver Creek Distillery and Warwick Distilleries. The two distilleries, owned by William Smith Collins, were built right next to one another and were clearly manufacturing whiskey for retailers in Missouri. One Missouri dealer advertising “Silver Creek Whiskey” was D.L. Keiser.

D.L., J.P., and C.W. Keiser had been steamer captains running passengers and goods along the Missouri River throughout the 1860s. By 1870, D.L. Keiser was operating a wholesale & retail grocery store out of Boonville, Missouri. His Boonville shop sold whiskey which had been distilled by George T. Stagg at the Spring Creek Distillery.

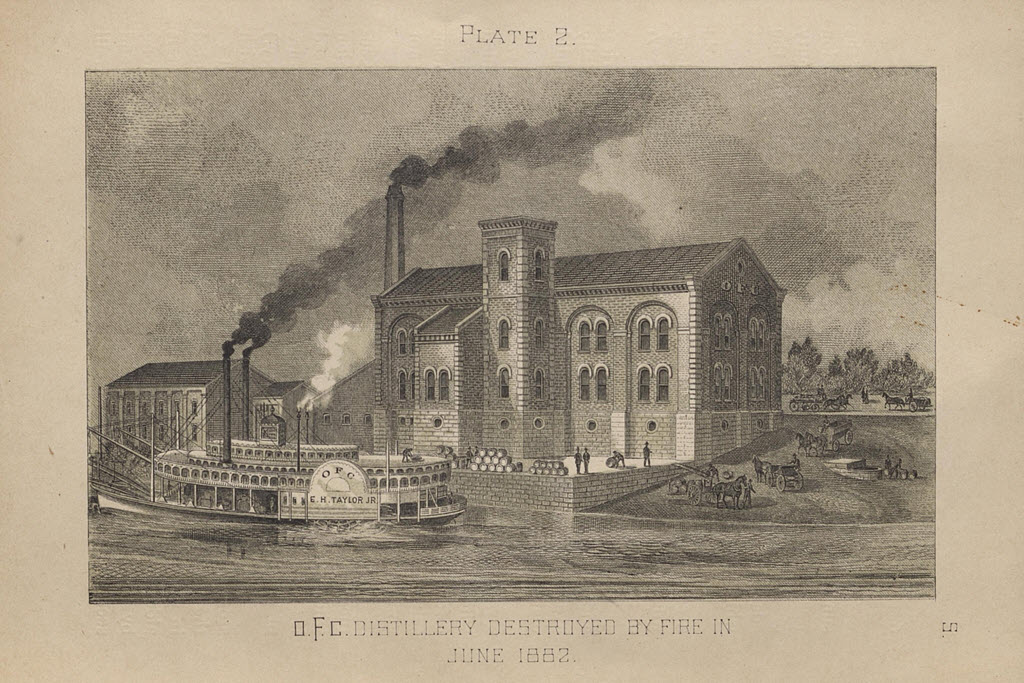

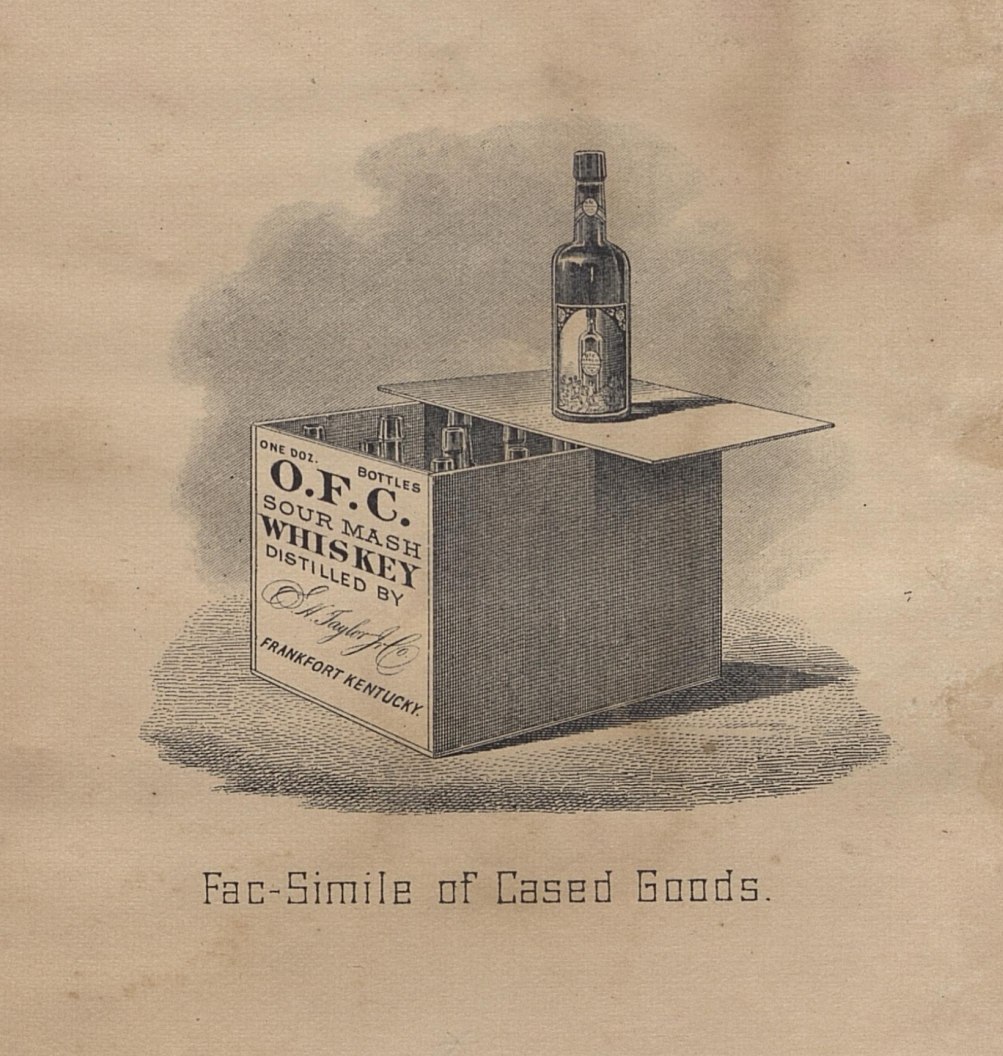

In 1871, George T. Stagg joined J.P. & C.W. Keiser to form a St.Louis-based general storage and commission business called “Keiser & Stagg”. It’s hard to say for certain what made George Stagg leave Kentucky, but perhaps he saw more potential in the distribution and sale of products than in his work at the distillery in Richmond. His business with the Keiser family did not last long, however. The partnership was dissolved during the summer of 1872, and by September, George was creating a new firm with a new partner. Oddly enough, this new partner was no stranger to him. George had been paying rent to his new partner, James A. Gregory, over a decade earlier in Kansas City while he had been selling leather and carriage goods as “Miller & Stagg”! James Gregory was 12 years older than George and had been in St. Louis since 1862 running a leaf tobacco business and operating a large commission business (since 1865). Their new firm, Gregory, Stagg & Co. would evolve from cold storage and commission sales to a highly esteemed wholesale liquor house by 1875 (Founded in 1872). Captain George T. Stagg had finally found the ideal business partner. Between the two of them, Gregory & Stagg had all the right connections for their wholesale liquor firm. Stagg, having been a distiller in Richmond, chose to source their products (Kentucky’s finest bourbons and ryes) from his old stomping grounds- W.S. Hume’s Silver Creek Distillery & Warwick Distilleries near Richmond…and Edmund H. Taylor, Jr’s O.F.C. & Kentucky River Distilleries near Frankfort.

In the previous post, we left George T. Stagg in in 1875 during the prime of his life, as he was turning 40. He had found a great business partner in James A. Gregory, and their wholesale liquor firm and commodities trading company was thriving in St. Louis, Missouri. While acting as distillers’ agents, Gregory & Stagg’s storefront at 218-220 North Main Street in St. Louis was also dealing in grain, cotton, leaf tobacco, hides, and other profitable goods. Captain George Stagg was still making regular visits to Kentucky to secure their whiskey stocks, and the newspapers were making note of his travels. By 1878, however, trouble was brewing.

In January 1878, Edmund H. Taylor, Jr., the prominent Frankfort, Kentucky distillery owner that Gregory Stagg & Co. had been doing business with for at least 6 years, suddenly found himself in financial trouble. The total debt Mr. Taylor had accrued was north of $500,000, and the financial hornets’ nest that he had stirred up with his creditors had also put George and James’ St. Louis firm in a very difficult position. They both traveled to Frankfort to meet with Edmund Taylor and negotiate a solution that would work for everyone. Gregory & Stagg used their own attorneys (Harris & Joy of St. Louis) to help negotiate a bankruptcy settlement for Taylor. He would declare bankruptcy and pay 20 cents on the dollar to his creditors, which would allow Gregory Stagg & Co. to save the $148,000 in advances and 1,500 barrels they owned, all of which were sitting in Taylor’s warehouses.

That same month (January 1st), Gregory & Stagg took on two new partners to their St. Louis firm: William S. Hume and John J. Fisher. W.S. Hume had taken possession of the Silver Creek Distillery in 1871, so his partnership ensured Gregory & Stagg’s continued access to Silver Creek Distillery’s whiskeys. (It’s unclear who J.J. Fisher was, exactly, other than another local commission agent based in St. Louis.) The firm now had sole agency for E.H. Taylor’s O.F.C. Distillery’s products, and they were expanding the import and export aspects of their business.

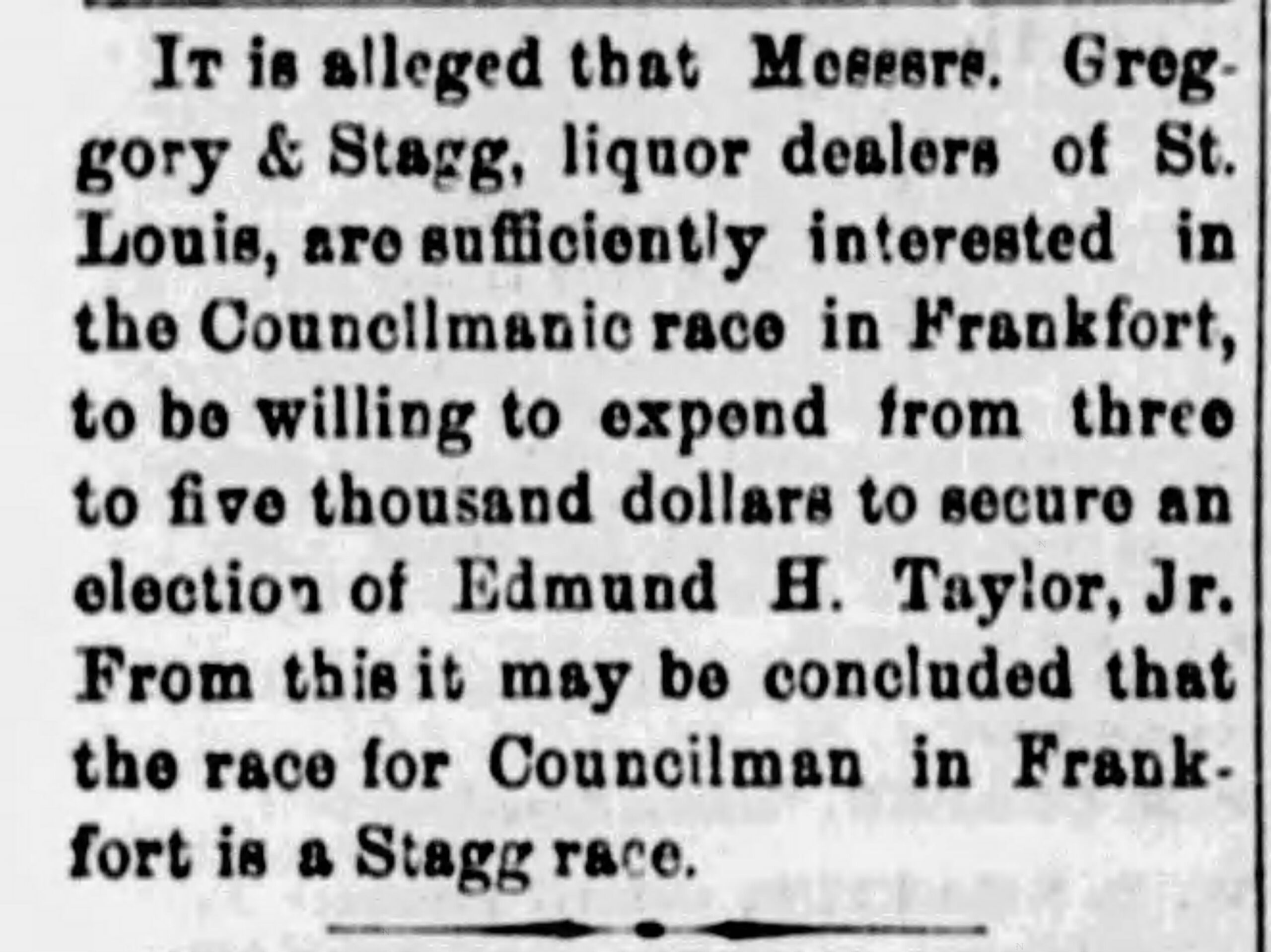

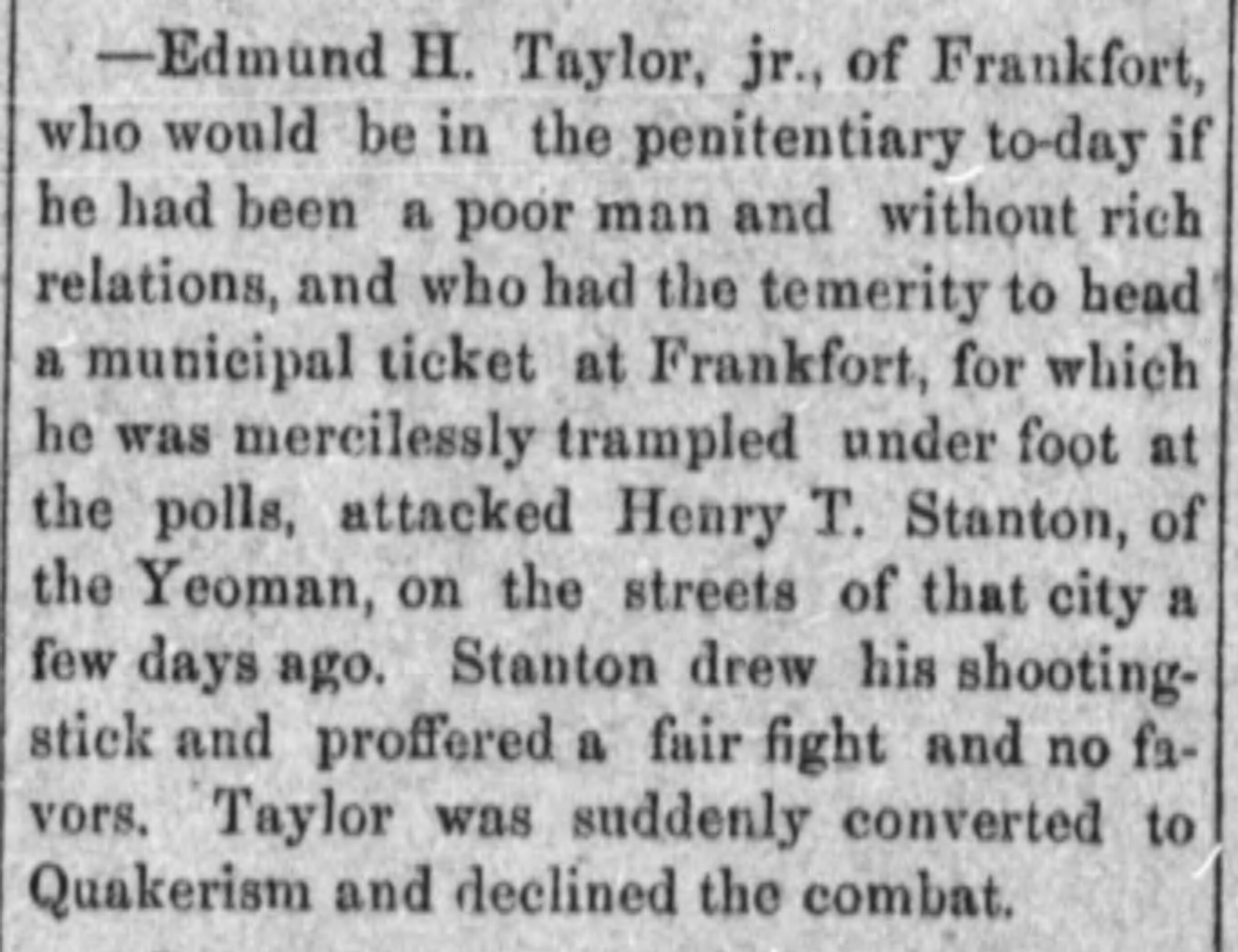

Meanwhile, in Frankfort, Edmund H. Taylor, Jr. was using his financial clean slate to return to politics and had begun to canvass for the role of City Councilman. Accusations were being hurled at Gregory & Stagg for funding Taylor’s campaign, and the local newspaper editors were not shy about denouncing the influence that Missouri businessmen were having on the vote, especially when they had so little love for Taylor. Many whiskey histories describe E.H. Taylor, Jr. as having been mayor of Frankfort for 16 consecutive years, but that’s not accurate. While Taylor did serve as mayor from 1871-1877, his legal and financial troubles (and indictments!) left him in a tight spot during the late 1870s. His association with George Stagg, however, seemed to be his financial and political saving grace.

In January 1879, George Stagg lost his wife, Bettie, and mother to his four living children, to heart disease. She died in St. Louis, but was moved to Richmond, Kentucky for her burial. George would re-marry several years later to a much younger woman named Essell Allwright (born 1862-1863).

On October 4, 1879, the “E.H. Taylor, Jr. Company” was incorporated by George T. Stagg, E.H. Taylor, Jr. and Gustavus J. Baeppler, a St.Louis-based tobacco dealer. The companies settled their debts and set their sights on the future. A new distillery was erected directly beside the O.F.C. Distillery in Frankfort in 1880. It was named the Carlisle Distillery after John G. Carlisle, who had served as a Senator for Kentucky’s State house (1866-1871), Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky (1871-1877) and a U.S. House Representative for Kentucky’s 6th district since 1877. It was George Stagg that chose the name, wanting to thank Mr. Carlisle for his political support of the liquor industry. The O.F.C. Distillery and Carlisle Distilleries would now rival the production capacity of the Silver Creek Distilleries in Richmond.

In 1882, James A. Gregory retired from active business, leaving a co-partnership to be formed between George Stagg, William S. Hume, and E. H. Taylor, Jr. The new firm was called Stagg, Hume & Co., and their new address relocated the company from their old home on Main Street to 104 North 3rd Street in St. Louis. In March 1884, William S. Hume, owner of the Silver Creek Distillery, retired from business. Stagg, Hume & Company was “dissolved with mutual consent”, leaving George Stagg to liquidate its business. Hume’s retirement may have been due to health concerns, because on September 12, 1885, William Hume died at the age of 54 from “inflammation of the bowels”. Hume’s Madison County distilleries, one the largest in the state, passed to his wife, Eugenia. Eugenia’s brother, Curtis F. Burnam of Cincinnati’s “Burnam, Bennett & Co.”, took control of the property and quickly merged with Stagg and Taylor to form the “Silver Creek Distillery Company” of Richmond, KY. While it may appear (as it so often does) that the company was based in Kentucky, its funding was still centered in Missouri. By the end of the 1886 distilling season, the Warwick and Silver Creek Distilleries manufactured over 9,000 barrels of whiskey, the equivalent of four hundred thousand gallons of whiskey. (Each barrel would have been 47-48 gallons, the normal whiskey barrel capacity at the time.)

George Stagg’s lengthening shadow may have been the reason that E.H. Taylor, Jr. chose to withdraw from their partnership in 1886. E.H. Taylor’s eldest son, Jacob Swigert Taylor, had established the J.S. Taylor Distillery on Glenn’s Creek (aka the castle-like Old Taylor Distillery) in 1879, but Edmund took over ownership after several years. He withdrew from his partnership with Stagg, but he continued to build on the company he shared with his sons by establishing the E.H. Taylor & Sons Company. (That company would find itself in financial trouble by the early 1890s, too. Perhaps Taylor was not the businessmen we assume he was!) Stagg & Taylor were going their separate ways.

In December 1887, the E.H. Taylor, Jr. Company was renamed as the George T. Stagg Company. E.H. Taylor had withdrawn from the company the year before, leaving the output of his O.F.C. and Carlisle Distilleries in the hands of his St. Louis counterparts. In 1889, the Carlisle Distillery manufactured 3,586 barrels of whiskey and the O.F.C. distillery filled 6,059 barrels. That whiskey was then packaged as “Old Taylor whiskey” with the signature of E.H. Taylor, Jr. on every label. This, of course, created a huge lawsuit against Stagg’s firm for infringement of copyright by Mr. Taylor, who was no longer with the firm. E.H. Taylor called the use of his name by Stagg fraudulent and misleading and demanded $50,000 damages and a perpetual injunction restraining the company from using his name. In 1891, Taylor was granted his injunction and was given his $50,000 in damages along with compensation for every bottle sold since he left the company in 1886, but the lawsuit would be appealed. These lawsuits surely took their toll on George Stagg, especially considering the fact that it was Stagg that saved Taylor from ruin a decade earlier. After the lawsuit was settled in the fall of 1891, George retired from business to travel for his health.

George T. Stagg had been suffering from lung trouble and went to California to rest for a while and then on to Florida. He brought his son, Stanley, and his wife, Essell, with him on his journey. It seems that George and Essell Stagg visited Ft. Myers with some regularity during the tarpon fishing seasons. While in Florida during May of 1891, Essell caught a huge 205-pound tarpon with rod and reel. George (56) may have been unwell, but his young wife (28) was in good health and capable of fighting a fish for an hour and a half! While enroute from Ft. Myers to Richmond, Kentucky, the Staggs stopped in Baltimore (Baltimore being the nearest shipping port for the final leg of their journey by train), but George would not leave that city. George Thomas Stagg died in Baltimore on May 24, 1893 at the age of 58. Essell and Stanley were by his bedside when he passed.

George died a wealthy man, but none of George’s children would inherit his business after his death. His eldest child, Lida, married Edwin J. Carter, who was involved in real estate in Austin, Texas. Stanley worked for the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. Thomas H. Stagg would work as a merchant in Frankfort, but it’s unclear if he had any association with his father’s business. Later in life, Thomas relocated to New York working as a statistician for the Journal American Newspaper. Frank, the youngest (born 1873), became a respected hardware merchant in Frankfort, KY and remained in that business until Prohibition. In an odd and somewhat ironic twist of fate, Frank G. Stagg would become associated with Schenley’s George T. Stagg Company over 35 years after his father’s death! During Prohibition, Frank became bookkeeper for the company, eventually becoming the company’s secretary treasurer. He remained with Schenley’s version of his father’s company until his death in 1942.

Part 3-

After George Stagg’s death in 1893, his fortune passed to his wife, but his company passed to George H. Watson. So…who was George H. Watson?!

In my last post, I explained that George Stagg’s sons did not inherit their father’s companies’ assets, but I’ve been unable to find any information alluding to why that may have been. I always understood that Stagg’s company passed to Walter B. Duffy after his death, but Duffy did not own any of those distilleries until at least 1898. There were 5 unaccounted years there, and the George T. Stagg Company invested a lot of money in advertising during those years, so someone had to be pulling the strings! What I found was that the company had passed to George H. Watson.

George H. Watson had already been with the company for years. When E.H. Taylor chose to dissolve his partnership with Stagg in 1886, Watson was 29 years old and working as Taylor’s bookkeeper. The leadership gap left by Edmund Taylor when he left the “E.H. Taylor Jr. Company” (owned by Stagg) to pursue separate ambitions with his sons at the J.S. Taylor Distillery (Old Taylor Distillery) would have been competently filled by George H. Watson who already held a leadership role at the OFC and Carlisle distilleries in Frankfort. (This information came from Brian Haaras book, Bourbon Justice.) After Stagg’s death in 1893, the main leadership role within George Stagg’s company was essentially passed on to the man already running Stagg’s Frankfort distilleries. Even if George H. Watson may seem like an unlikely candidate to take George Stagg’s place within such an important company (We’ve never heard of him, right?!), his appointment becomes less unlikely when you consider just how well-connected George Watson had become by 1893.

In 1892, George H. Watson married Alice Berry Orbison, daughter of Hiram Berry and Eleanor Hume. Hiram Berry had been associated with W.A.Gaines & Co. and Eleanor may have been related to William Stanton Hume, the famous distillery owner of the Silver Springs Distillery in Richmond (though I have yet to prove that)! Watson’s wedding certainly reflects how wealthy and well-connected he had been. He was a breeder and trader of thoroughbreds, as well. In fact, George Watson bought the famous 286-acre “Bosque Bonita” farm in 1898 where he raised and bred champion thoroughbreds like his famous stud, “John G. Carlisle.” (Yes, the horse was named after the same Senator the distillery was named after. Some of the Bosque Bonita Farm in Versailles, KY has become Lane’s End Farm today.) Stanley Stagg, George T. Stagg’s eldest son, was also noted as being an important guest at Watson’s wedding in 1892. Stanley’s presence at the wedding is notable when you consider the fact that he had been traveling with his father and stepmother (since 1891) when the Watson/Berry wedding was taking place! Stanley Stagg’s presence at the wedding doesn’t just show his connection to the married couple, it also shows that he made a special trip to attend, representing the Stagg family while his father was dying of tuberculosis. I think it can be assumed that George H. Watson was a fine candidate and trusted associate of the Stagg family when he assumed control of the OFC and Carlisle properties after George T. Stagg’s death in 1893.

Legal disputes between George T. Stagg & Co. and E.H. Taylor & Sons were ongoing throughout the early 1890s, so perhaps it’s not odd that George H. Watson was not mentioned very often in the papers. In 1894, however, Watson was noted as hosting and entertaining dignitaries at the OFC and Carlisle Distilleries with the help of Benjamin H. Blanton, bookkeeper, and Will Jenkins. (We’ll get back to Ben H. Blanton, Albert B. Blanton’s big brother, later!)

I wanted to make this next piece of information a separate post, but I cannot leave this historic whiskey gem out of the story. I may have to repost it later, too!

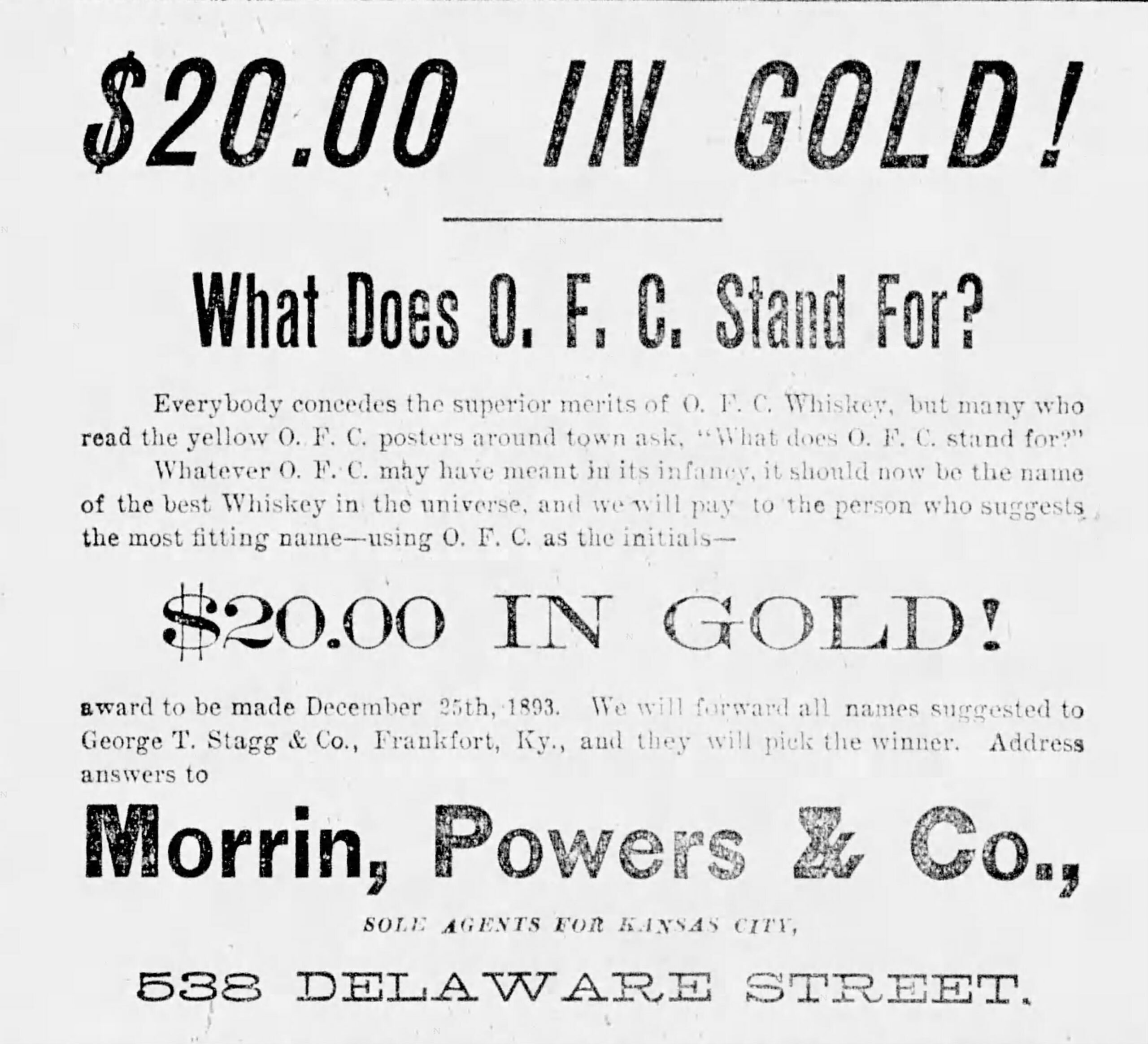

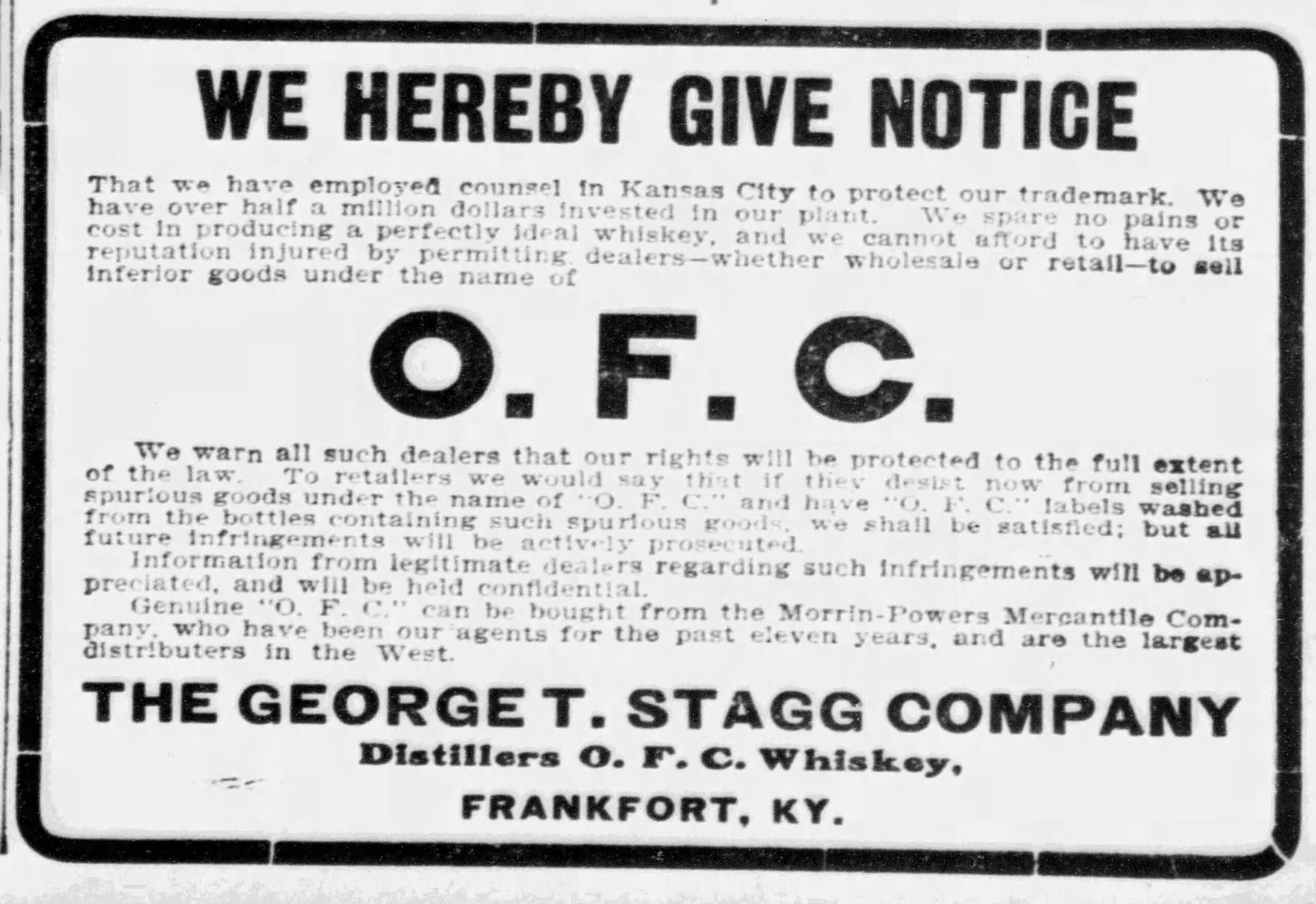

In July 1893, less than 2 months after the death of George T. Stagg (May 24, 1893), a Kansas City liquor firm specializing in the sale OFC whiskey placed an ad for a contest. It read:

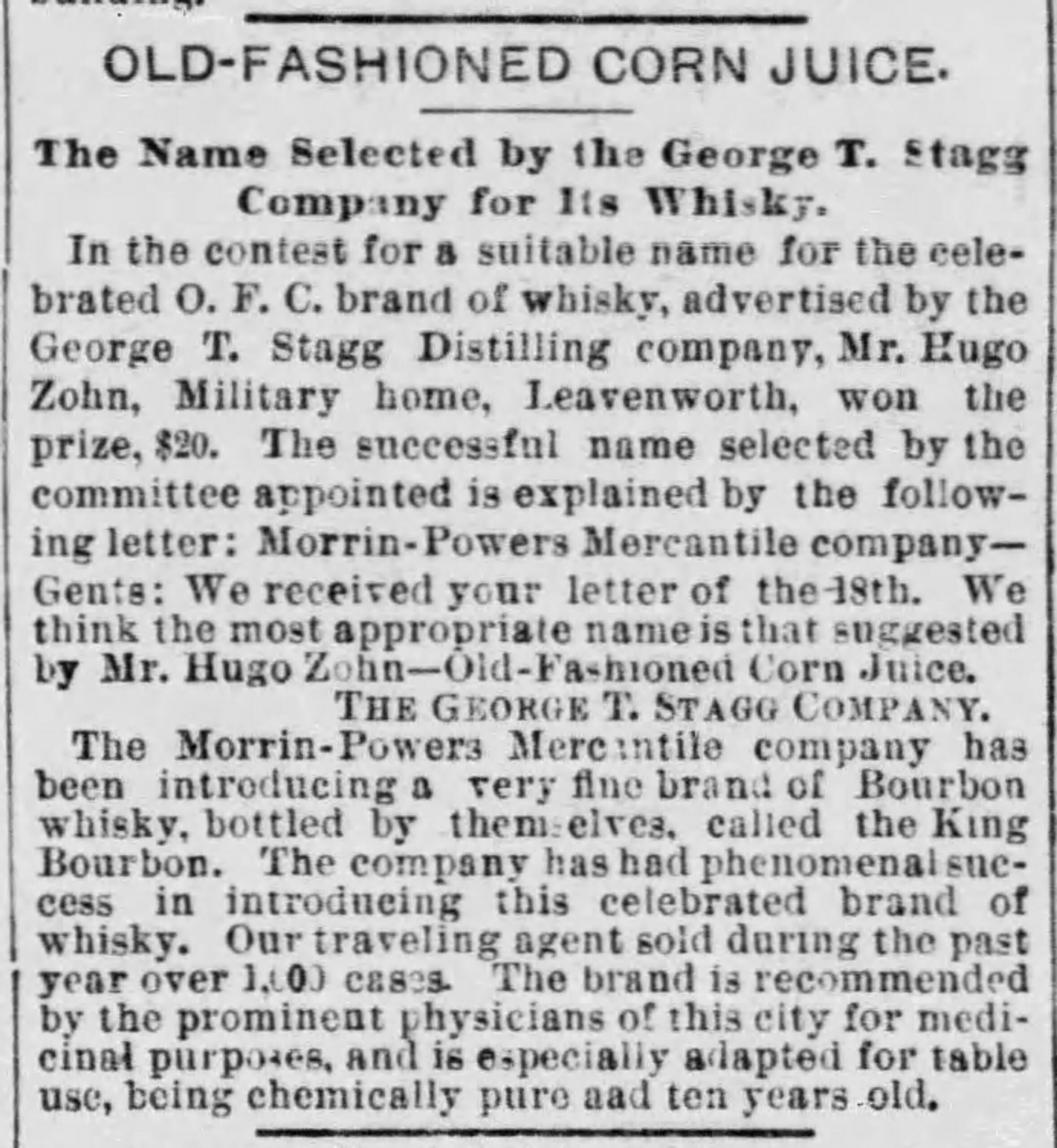

“$20.00 IN GOLD! What Does O.F.C. Stand For?,” the ad asked consumers. “Everybody concedes the superior merits of O.F.C. Whiskey, but many who read the yellow O.F.C. posters around town ask, ‘What does O.F.C. stand for?’ Whatever O.F.C. may have meant in its infancy, it should now be the name of the best Whiskey in the universe, and we will pay to the person who suggests the most fitting name — using O.F.C. as the initials — $20 IN GOLD! Award to be made December 25th, 1893. We will forward all names suggested to George T. Stagg & Co., Frankfort, Ky., and they will pick the winner.”

This ad almost strikes me as a snub to E.H. Taylor, Jr., who had been labeling his products as “Old Fashioned Copper” beneath his own patented label signatures. On January 2, 1894, the Kansas City company (Morrin-Powers) placing the ads was true to its word. They awarded Mr. Hugo Zohn, with a military home in Leavenworth, Texas, with 20 dollars in gold for “the most appropriate name suggested.” His suggestion? “Old Fashioned Corn Juice.” Yep. You can’t make this stuff up, folks! I can only imagine how E.H. Taylor reacted to this in 1894! You have to wonder if the publicity stunt was done deliberately to aggravate Taylor and to remind him who owned the company after Stagg’s death, or if it had been done to simply drum up business for OFC whiskey! Either way, it’s a great piece of American whiskey history! (Good though, right?!)

Let’s get back to the story…

As we established earlier, most historic references explain that Walter B. Duffy, the man behind Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey, took ownership of the Stagg properties the 1890s, which is accurate, but Duffy did not truly own those properties until 1900. “The Kentucky River Distillery Company”, however, WAS incorporated with a capital stock of $5,000 in 1898. The incorporators of the company were Walter B. Duffy of Rochester, N.Y., A.S. Bigelow of Washington City, and George H. Watson of Frankfort, KY. Here, we begin to see the financial association of George H. Watson with Walter B. Duffy, and the transition that was beginning to take place between the two men.

E.H. Taylor, Jr. had been flexing his muscles with the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897, but the real power in Kentucky’s whiskey industry was being established during the late 1890s by Samuel M. Rice’s American Spirits Manufacturing Company (ASMC), which had been building its monopoly of the bourbon trade for years. By 1899, the ASMC created a subsidiary known as the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company. The Kentucky bourbon trade, or at least 90% of Kentucky’s bourbon distilleries, had fallen in line with “the Whiskey Trust”, but there were hold-outs. Among these holdouts were the Frankfort distilleries.

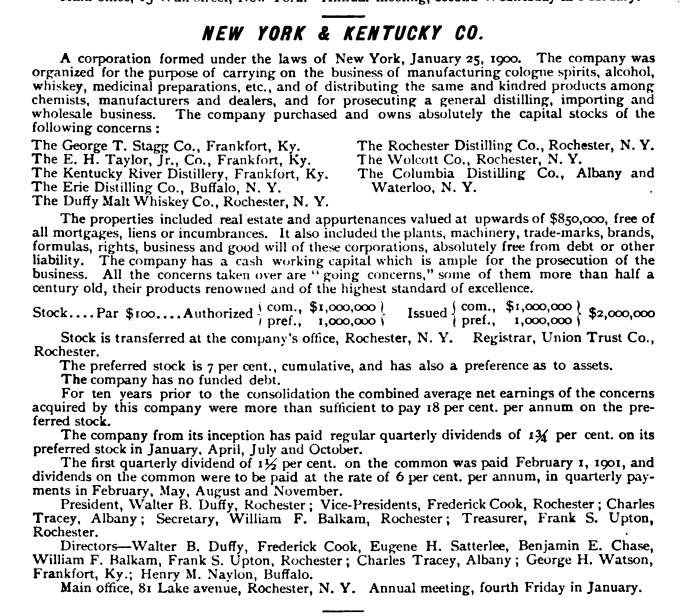

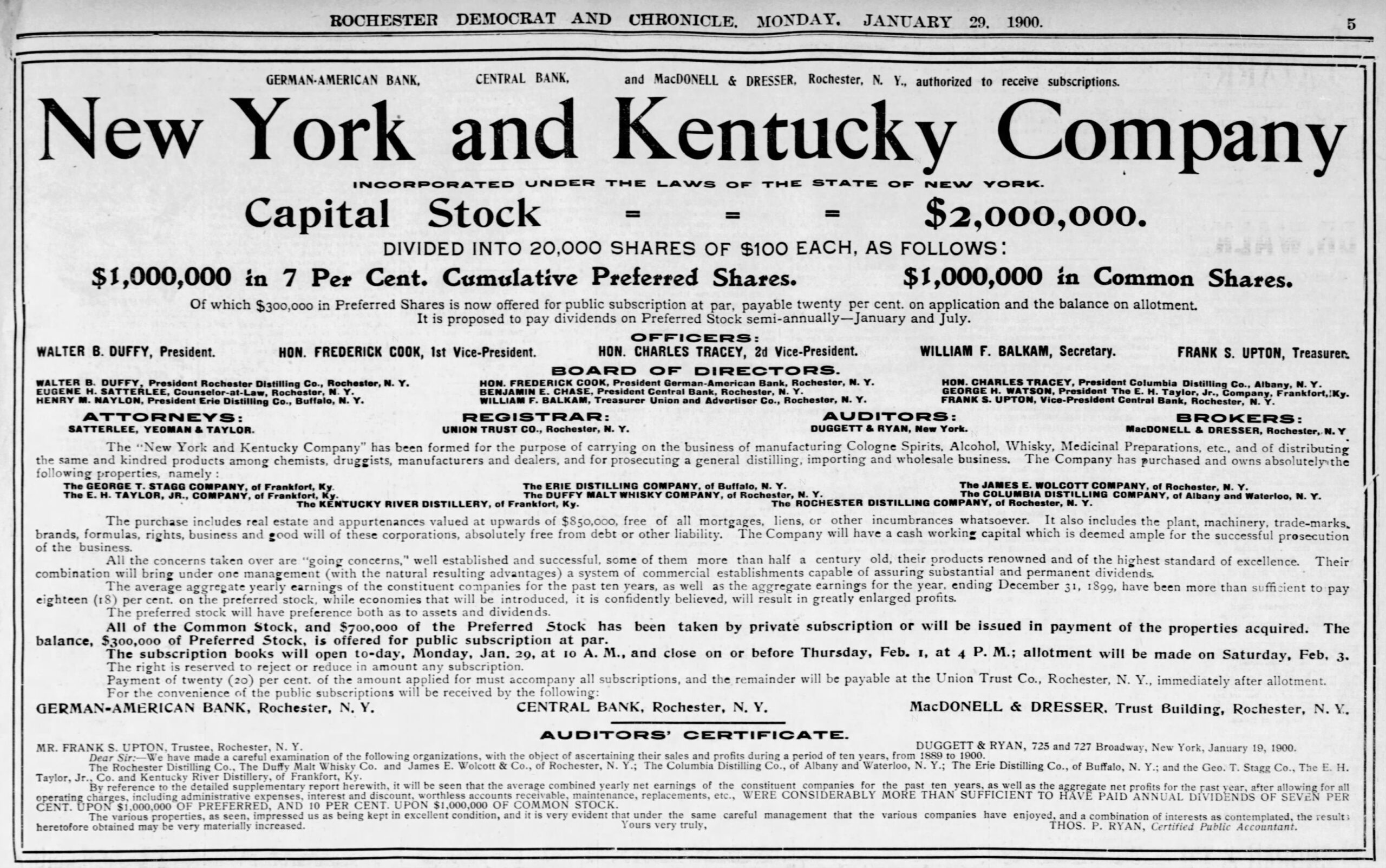

In the spring of 1899, many of Kentucky’s most influential bourbon distillery owners were “threatening” to retire to their country estates and yachts and leave their distilling legacies in the hands of the ASMC. Several of the companies refusing to fall in line with these buyouts were also among the state’s most desirable properties, several of which were owned by George T. Stagg & Co. In 1900, a separate combine, known as the “New York and Kentucky Company” was incorporated with a capital of 2 million dollars. Its home offices were based in Rochester, N.Y., and its officers were Walter S. Duffy- president, Hon. Frederick Cook- 1st vice president, Hon. Charles Tracy- 2nd vice president, William F. Balkham- secretary, and Frank S. Upton- treasurer. George H. Watson, president of the E.H. Taylor, Jr. Co. (not to be confused with E.H. Taylor, Jr. & SONS Co.) of Frankfort, KY, was named director of the new company. Here we see the transition of ownership of the Stagg properties taking place. (It’s also worth noting that George T. Stagg’s widow was remarried in 1899, which may have affected the company finances if Mrs. G.T. Stagg had any ownership stake in her late husband’s businesses.)

The New York & Kentucky Company took charge of the following subsidiaries in 1900: The George T. Stagg Co. of Frankfort, KY, The E.H. Taylor, Jr. Co. of Frankfort, KY, the Kentucky River Distillery Co. of Frankfort, KY (established 2 years earlier), the Erie Distilling Co. of Buffalo, NY, The Duffy Malt Whiskey Co. of Rochester, NY, the Rochester Distilling Co, of Buffalo, NY, the James E. Wolcott Co. of Rochester, NY, and the Columbia Distilling Co. of Albany, NY. To put it plainly, Walter Duffy was creating a very valuable alternative to the Whiskey Trust by establishing his own partnership with the Stagg Company. It’s obvious that George H. Watson, through his partnership with Duffy, was openly willing to become the opposition to a seemingly unopposable company.

Part 4-

Walter Duffy’s New York & Kentucky Company took ownership of the Stagg Company’s OFC & Carlisle Distilleries in 1900. The NY & KY Co. also owned the George T. Stagg and E.H. Taylor, Jr. Companies, but it’s important to stress that those companies did not represent physical places, per se; They were the corporate entities which owned distinctive brands and managed the business of the Frankfort distilleries, which were responsible for manufacturing those brands. (If anyone is wondering what happened to the Silver Creek Distilleries, previously owned by Stagg, they were sold, like so many others, to the Whiskey Trust, aka the American Spirits Manufacturing Co., in 1899. William Hume, Jr. remained with the distillery his father owned, but his brother Edward, chose to stay with the Stagg Company at the OFC distillery. The Silver Creek properties would be bought out by the Bernheim Distilling Company in 1906.)

Edmund H. Taylor, Jr., who dissolved his partnership with George T. Stagg and abandoned the companies he founded in 1886, established a NEW company for himself across town (8 miles south of the OFC and Carlisle distilleries in Frankfort) His new firm, dubbed “E.H. Taylor, Jr. & Sons”, would sit in direct competition with the Stagg/Duffy concern. The “Sons” part of the company’s name made it distinct from the Stagg companies (his old companies), or so Taylor insisted- a distinction which would probably never hold up in court today, but which seemed to do the trick for the politically well-connected Taylor at the time. His new brand, which he dubbed “Old Taylor”, was now being manufactured at his son’s distillery along Glenn’s Creek in Frankfort. What was known as the J.S. Taylor (Jacob Swigert Taylor) Distillery was changed to the “E.H. Taylor, Jr. & Sons” Distillery, or “Old Taylor” Distillery. Taylor had been incensed by the George T. Stagg Company’s use of his name and had been in and out of court with Stagg since he left the company. Now that George T. Stagg was dead, Taylor was more than happy to continue to sue the new owners of his old brands. By the time Duffy bought out the Stagg companies in 1900, Taylor’s case against Stagg had already been bouncing around in appeals courts for over a decade.

As far as the OFC and Carlisle plants were concerned, their ownership passed to Walter B. Duffy with his main offices in Rochester, N.Y. Their management and presidency, however, remained with George H. Watson, George Stagg’s replacement. George Watson’s offices were based in St. Louis, so he entrusted the bookkeeping in Frankfort to his private secretary, Benjamin H. Blanton, Jr. As head bookkeeper for the George T. Stagg Co., Ben Blanton championed the use of a new method of record keeping for the company through his modification of a complicated “Italian system” of recording balances. Using this method, several bookkeepers could work on a set of books while maintaining the confidentiality that should only belong to the head bookkeeper. Ben Blanton was able to manage and easily keep track of all the books related to the Stagg companies without compromising anything as he did so…and made the company a lot of money in the process! Ben Blanton was highly valued by Mr. Watson, but in 1901, due to his own health concerns, he chose to strike out on his own and make his own way. He purchased a grocery in Knoxville, Tennessee and left the firm, but not before passing his torch to his younger brother, Albert. Albert Bacon Blanton was 20 years old in 1901, but he had been under his brother’s wing during the last several years, so his transition was a smooth one.

In May 1903, William H. Lee, one of the best-known wholesale liquor dealers in St. Louis, unexpectedly passed away of pneumonia. His death forced the reorganization of his huge St. Louis-based firm. The company’s new president became J.S. Morrin of the Morrin-Powers Mercantile Company. You may remember Morrin-Powers from my last post describing their offering a reward of 20 dollars in gold for the best new slogan for O.F.C. whiskey. (The winner dubbed it “Old Fashioned Corn Juice!) In July 1905, George H. Watson purchased the William H. Lee Company. As one of the largest distributors of Stagg’s O.F.C. whiskeys in St. Louis, the company would become a major distribution hub for the Stagg company. By 1909, Watson was moving the company’s main offices from St. Louis to Chicago. While they would maintain their St. Louis presence, Chicago would become the Stagg Company’s new headquarters. While George H. Watson would relocate to Chicago to run the company, Albert Blanton remained in Frankfort to operate the OFC and Carlisle Distilleries as superintendent.

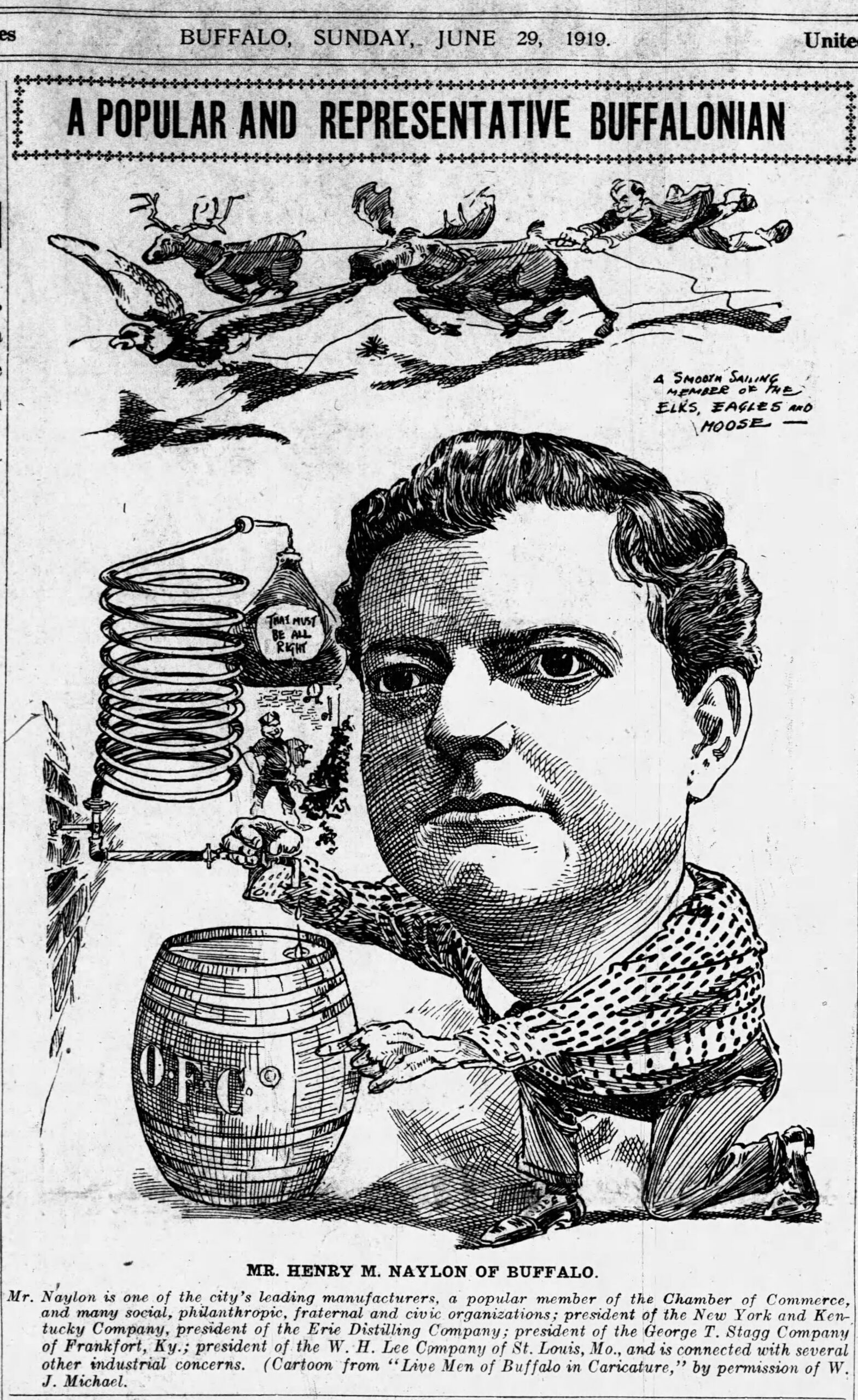

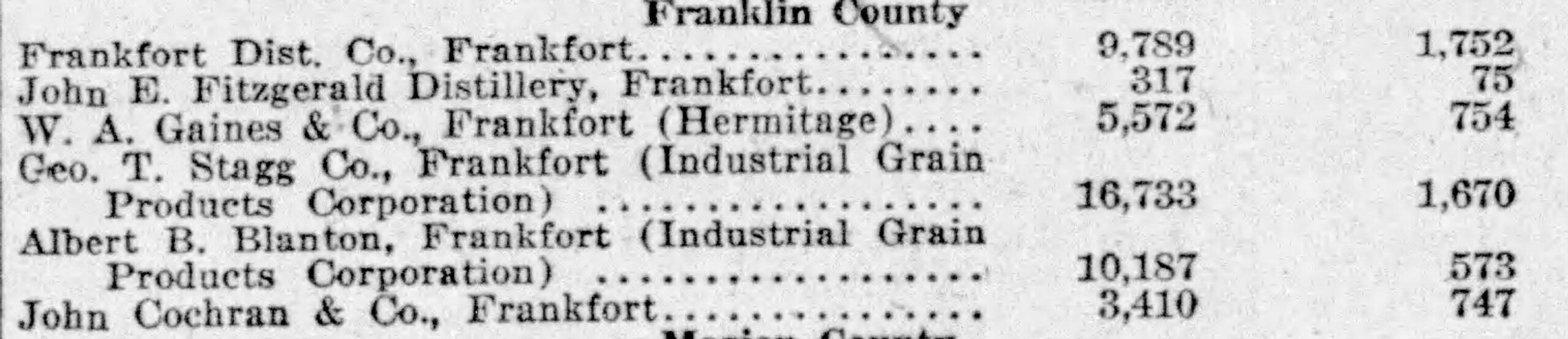

A.B. Blanton continued to operate the Stagg distilleries in Frankfort until the advent of Prohibition. In 1918, the New York & Kentucky Company, a $5 million company, was dissolved in anticipation of the passage of the 18th amendment. In 1919, the distilleries (and the W.H. Lee Co.) were sold by Albert Blanton to Henry M. Naylon, president of the Erie Distilling Company (Buffalo, N.Y.) and founding member of the New York & Kentucky Company. Naylon chose to transform the properties into industrial alcohol plants, a decision that had been reinforced by the movement of the nation toward Prohibition during the First World War. The OFC and Carlisle Distilleries became known as the Industrial Grain Products Corporation. Albert Blanton remained superintendent of the plants throughout the exchange.

The OFC Distillery property was able to obtain a license to operate as a concentration warehouse in 1922. Its use as a production facility for industrial alcohol during Prohibition made it an excellent candidate to manufacture medicinal whiskey in 1929 when the US government began handing out permits to distillers. By 1929, the plant had been purchased by The Schenley Products Co., led by the Jacobi brothers and Lew Rosenstiel of Cincinnati, Ohio. The plant’s facility was intact and operational, and Colonel Albert Blanton, now nearing 50 years old and in the prime of his life, was ready and willing to bring Frankfort’s OFC distillery back online. When history describes the “George T. Stagg Distillery” manufacturing medicinal whiskey during Prohibition, it’s describing the old O.F.C. plant. The plant suffered a large fire in 1932, but by Repeal in 1933, Schenley brought in Frank Stagg to represent his father’s name for the company. Albert Blanton remained president of the company, with Frank Stagg acting as secretary for the company. The rest, as they say, is history.