American whiskey history tends to focus its spotlight on company presidents and brand owners. Whiskey barons like E.H. Taylor, Albert Blanton, and George Garvin Brown have been lionized by the modern whiskey industry, but the men who managed production and operated the machinery in the still house have largely been ignored. While whiskey brands have always been built upon marketing paid for by distilling company owners, the quality of the whiskey was only as good as the skilled craftsmen that made it. The distiller was the unsung hero behind every famous, historic brand. The history of American whiskey cannot be told properly without telling the stories of the men working the stills and tending the yeast. Their stories cannot neatly fold into what we know about the modern whiskey industry without first addressing the elephant in the room- Prohibition. Very few distillers were able to maintain their role within the industry after the 18th amendment officially put an end to their careers! There were exceptions, however, that were able to successfully navigate National Prohibition and Repeal and maintain their integrity as professional distillers. One of the great American distilling families to beat the odds stacked against them by Prohibition was the Schreiner family.

The Schreiner family’s legacy has been inconspicuous, overshadowed by the histories of the famous companies they worked for: Schenley, J.B. Wathen Co., the White Mill and Lynndale Distilleries, James E. Pepper Distillery, Belle Meade Distillery, Old Quaker Distillery, Bernheim Distillery, among others. While the Schreiner name may not be well-known, their impact on America’s whiskey trade cannot be ignored.

The patriarch of the Schreiner family in the United States was Antone Schreiner. Antone was born in March 1838 in the historic state of Baden-Württemberg in the southwestern region of modern-day Germany. While the exact reasons for his departure from his homeland are unclear, a very young Anton emigrated from Germany to the United States. By the age of 22, Anton and his wife, Feronica O. (Beraenger) Schreiner, were living in Cincinnati, Ohio. He had been working as a scissors’ grinder, which likely did not support his new family, so while Frederick was still a toddler, Anton and Feronica moved to New Albany, Indiana. There, Antone took on construction work, building vaults for a safe manufacturing company. The Schreiner family continued to grow with the birth of their only daughter, Maria, in 1862. Anton and Feronica would suffer a terrible loss on March 29, 1865, with the death of their second-born son, Joseph, on when he was only 3 months old. Times were surely difficult for the couple, even as the Civil War was coming to an end. New Albany businesses had been boycotted by both the North and the Southern Confederate states during the war, which surely affected their life and their community. (The North considered New Albany to be too friendly to the South, and the Confederates boycotted it because it was in a Union state.) Despite their hardships, Anton was able to maintain work as a cutter and grinder, and two more sons were born to the couple; Andrew Joseph Schreiner was born on June 6, 1866 and, their youngest, Joseph, on July 16, 1869.

The 1870s would usher in a new industrial era for New Albany and for the river-port cities along the mighty Ohio River. The railroads would shift the city’s economy away from shipping and steamboat building toward ironworks and rolling mills. New Albany had begun to prosper, and in 1873, Antone Schreiner bought a home for his family on Main Street. Just when the family seemed settled, the Schreiners would face tragedy once again. On July 21, 1875, Feronica was killed suddenly in a wagon accident. Without a wife or mother to his children, Antone hastily remarried. His second marriage to Margaret Walter would not last long. She abandoned him, and Antone was forced to sell his family’s home for a small fraction of what he paid for it.

By 1880, census records show Antone living alone in Cincinnati. He was forced to leave his sons, Andrew and Joseph, behind in New Albany. The 14 and 11-year-old boys would live together for several years at St. Vincent’s Male Orphan Asylum, also known as “the Highlands”. It was not uncommon during the Industrial Revolution for widowed or abandoned single parents to leave their children behind in orphanages while they sought employment in other cities. It was certainly preferable to being forced to decide between paying rent or feeding your family, while an inadequate income made either choice impossible, anyway! Anton appears to have returned to Cincinnati to take on work as a shoemaker after being abandoned by his wife. By 1882, his boys were finally able to follow him there.

Andrew J. Schreiner joined his father at work as a shoemaker. His working as a shoemaker, oddly enough, may be a link between A.J. Schreiner, Sr. and the liquor industry! In Cincinnati, there were several crossovers between liquor men and shoe companies! This was largely due to both shoes and whiskey being very big American industries, both centered in Cincinnati around the turn of the 20th century. Cincinnati liquor men invested in profitable businesses wherever they were found- banks, coal, railroads, whiskey distilleries, and yes, even shoes. The distilling companies that A.J. Sr. would become associated with throughout his career, even those in Kentucky and Indiana, were connected to large Cincinnati firms. A.J. Sr’s most famous future employers, Lewis Rosenstiel and Lester E. Jacobi, became the owners of a 32-year-old Cincinnati operation called the Sachs Shoe Manufacturing Company in 1919. While the Schreiner men would not have worked for that specific company, it’s curious to imagine which of Cincinnati’s many tanneries and shoemakers the Schreiner men worked for! Whichever it was, their leap from shoemaking to the distilling industry was not as big a leap as one might imagine.

Over the next decade, Andrew J. Schreiner met his wife, Margaret “Effie” Combs, and relocated to Louisville, Kentucky. They married on January 21, 1892. Around that time, Andrew took a job working for the J.B. Wathen Company in Louisville, though not as a distiller. It is possible that his father-in-law, Lutz Combs, provided “an in” for him, not only by living (and farming) in the distilling city of Louisville, but also by trading in corn meal, a necessary staple in the production of bourbon whiskey. Andrew and Effie would go on to have 6 children together: Ethel, born in March 1895, Fulton Leslie, born August 1896, Alvin Douglas, born October 1898, Florence, born in 1905, Andrew Joseph, Jr., born February 1907, and Lutz Frederick, born September 1910.

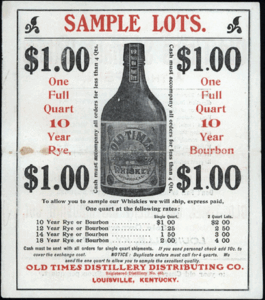

It is unclear when Andrew J. Schreiner, Sr. began working shifts in the still house at the Old Times Distillery. While it has been supposed that A.J., Sr. began his distilling career in the 1800s, the US census in 1900 for Louisville lists A.J. Schreiner, Sr.‘s occupation as “blacksmith”. Blacksmithing may, in fact, have been his role at the Old Times Distillery before the turn of the century. Since 1878, when the distillery was built (just west of the J.B. Wathen Distillery at 28th and Broadway in Louisville), its original owner and president, John G. Roach, had been known within the industry for his use of barrels held together by 10 iron hoops! While this number may seem excessive, it certainly made his barrels unique and would have required a full-time working blacksmith at the distillery. Old Times was also known for its hundreds of hand-stirred mash tubs and its modern boilers and engines, all of which would be easily managed by a young man like A.J. from New Albany, Indiana with experience in the construction of iron safes.

The Old Times Distillery (RD #297) changed hands several times since its construction in 1878. In 1886, it was sold to Andrew Biggs, owner of the Mellwood Distillery. After Bigg’s death in 1889, it was sold again to Charles E. Lemmon. In October 1895, the distillery passed again, at least in part, to Messrs. Rosenfield Bros. & Co. (the Chicago-based liquor firm which owned the Sunnybrook Distillery), though C.E. Lemmon appears to have maintained an important role within the company. One can begin to see how a distillery worker might be kept on during these ownership changes while taking on new, more important roles within the plant. To complicate things further, the Old Times Distillery was sold again to the Kentucky Warehouse and Distilleries Company, a subsidiary of the American Spirits Distilling Company (the newly incorporated Whiskey Trust) in 1899. As part of a newly established combine of many Kentucky distilleries, the Old Times Distillery would continue to function as it had before, only this time, it operated under new corporate management. While these changes in ownership may seem chaotic, they would not have disrupted the activity of the distillery itself. Ownership changes were on paper. The upheavals in ownership would have created more disruption for the distillery company’s banks and lawyers than it would have affected the activities of the distillery or its employees.

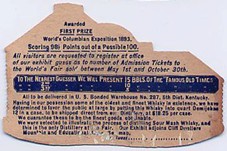

By the turn of the century, Andrew Schreiner had become firmly settled in Louisville with his family. He had three children, though he and Effie had suffered the loss of a child, as well. The Old Times Distillery was thriving under the ownership of the Whiskey Trust. In 1904, Charles Lemmon secured the exclusive privilege of selling bottles of whiskey at the World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri- the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. This seven-month spectacle showcased thousands of objects from all around the world and drew at least 19 million visitors to St. Louis. Old Times Distillery not only secured the incredibly valuable right to sell whiskey to these millions of visitors, they also managed to build a miniature, 100-bushel-a-day, distillery capable of distilling old fashioned sour mash whiskey! The small-scale distillery demonstrated for passers-by how whiskey was made. At a cost of $20,000, there’s little doubt that Andrew Schreiner contributed to the construction of the model distillery. Old Times Distillery had done something similar during the previous decade for the 1893 World’s Fair Columbia Exposition in Chicago, but the company was forced to dismantle their model distillery after complaints were made by a local Internal Revenue officer. (Chicago distilling men were likely “put out” by Old Times Distillery’s display and quickly had the ambitious model removed.) Charles Lemmon had to fight to restore Old Times’ claim to the highest scores awarded to a whiskey in the newspapers, as well. Lemmon would not make the same mistake twice, so he doubled down on Old Times’ representation and visibility at the 1904 World’s Fair. The investment would pay off for the company. Andrew Schreiner Sr., it appears, would also benefit from the company’s windfall by taking on more responsibility at the distillery. The first decade of the 20th century marked the launch of the Schreiner family (more specifically Andrew J. Schreiner, Sr.) into leading roles at Louisville’s most important distilleries.

While Andrew was finding success in the distilling industry and raising his family in Louisville, Kentucky, his younger brother, Joseph J. Schreiner, was forging his own path in the mining town of Butte, Montana. While it’s unclear how Joseph came to settle in Butte after leaving Indiana, by 1908, he had built his own gaming enterprise as a bookie.

At the turn of the 20th century, Butte’s population had grown to 40,000, and its racetracks were drawing large crowds. Butte’s racetrack for horses was built in 1888, and its dog track followed a decade later. By 1898, the greyhounds, known affectionately in Butte as “Cousin Jack racehorses”, had become as popular as “the ponies”. J.J. Schreiner was placing ads in the “Butte Miner” claiming that his clients could win the most money with his picks. The Montana legislature wouldn’t make gambling on dog and horse races illegal until 1914, so J.J. pushed his luck as far as he could, while he still could. Joseph claimed he was “The Man Who Knows” in his early ads, and by 1911, he claimed that he was the “Wizard” of winning picks at the tracks. Unfortunately for J.J., he was arrested in 1911 for giving women “fake tips”. A local ordinance in Butte had made it unlawful to cheat by dispensing fraudulent information, but Joseph argued that his information was based on “intimate knowledge of the ponies”, so his business was deemed legitimate.

J.J. Schreiner continued to appear in Butte’s newspapers into the 1910s. His betting office was also licensed as an “intelligence office” in 1911, which allowed him to legally provide tips and specialized information to the public. He would parlay his horse track betting with the business of land claims, as well. J.J. wrote and filed many claims for Montanans wishing to settle on oil land in Wyoming. Whether or not those claims were legitimately on oil land was brought into question in 1913 by local courts, but the part played by J.J. in those sales was never called into question. He was just the bookmaker, after all.

J.J. Schreiner had earned a reputation as an expert horseman in the western racing circuits, but he had begun to make his way back east in the mid-teens. By 1915, he was being spotted by reporters at eastern tracks and in Kentucky. He married Rose E. Simon in Indiana in 1917 (Rose was born in Indiana and had family there). While it’s not clear how the couple met, Rose’s brothers operated a wholesale liquor firm at 121 3rd Street in Louisville. It appears that J.J. was settling comfortably into the racing scene in Louisville, because the couple chose to reside in Louisville after their marriage. By the 1920’s, Kentucky was one of only three U.S. states that allowed horse track betting. Churchill Downs had implemented a “pari mutuel wagering system” in which the odds were not fixed, and bets are placed against other betters in a pool of funds rather than by a bookmaker. This is not to say that illegal betting was not still taking place on the side, it was being done in a more civilized, Kentucky-Colonel-approved way. J.J. must have been spending plenty of time with his nephews, as well, because Andrew J. Schreiner Sr.’s sons would follow in J.J.’s footsteps in the years to come.

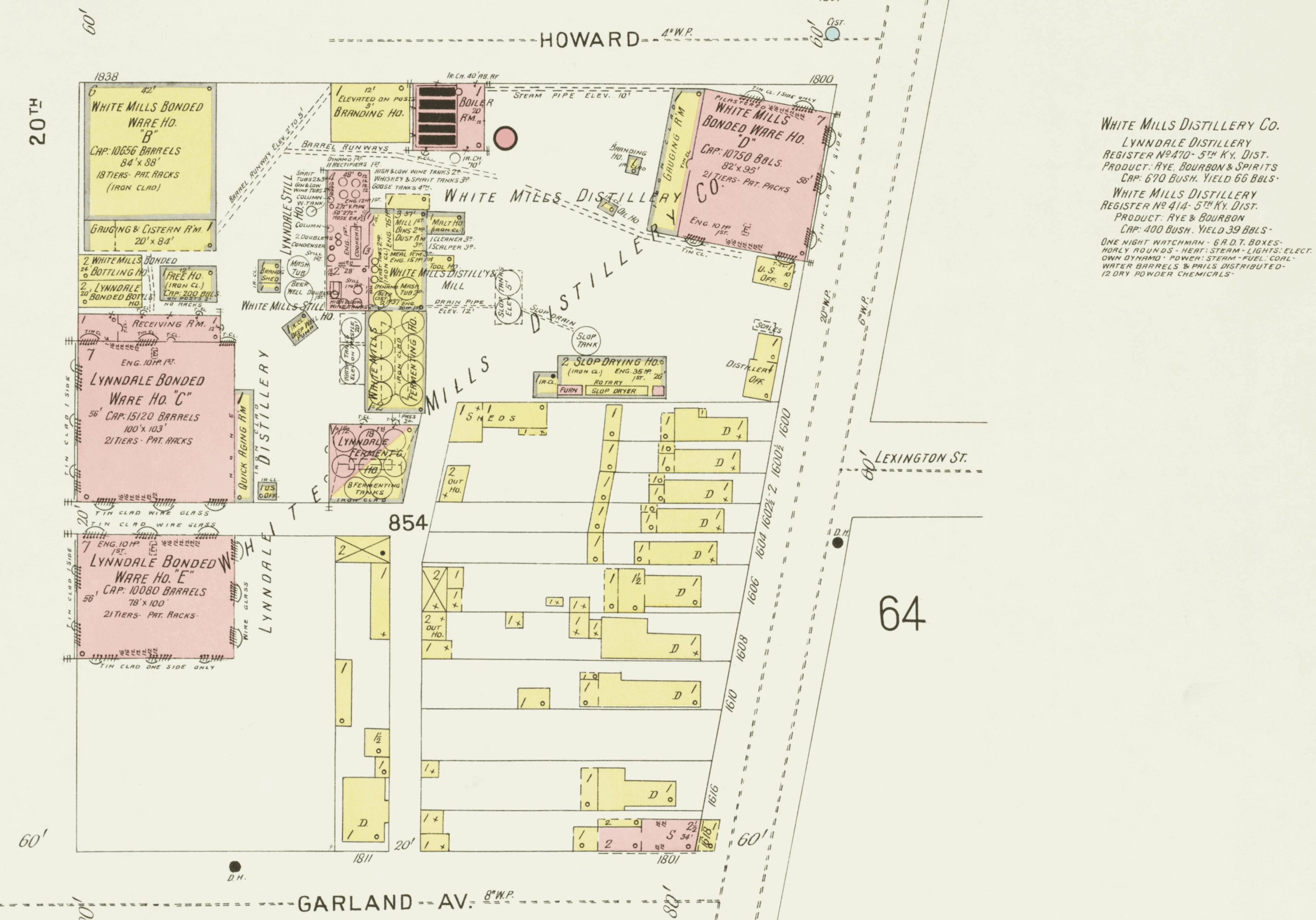

While Joshua J. Schreiner was settling down, his older brother, A.J. Schreiner, Sr., was moving up in Louisville’s distilling industry. After 1899, about 90% of the bourbon distilleries in Kentucky had been acquired by the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (aka the Whiskey Trust). The distilleries were combined and placed under the management of the Kentucky Warehouse and Distilleries Company, a subsidiary of the American Spirits Manufacturing Company. This new management fostered a consolidation of resources for the members of the combine. Some distilleries were shuttered, while others were asked to limit or increase their scale of production. Distillers and workers from these distilleries were often shuffled around, taking on work where work was available. It was during this time that A.J. Schreiner, Sr. came to work for the White Mills Distillery (RD #414) and its newly constructed sister facility, the Lynndale Distillery (RD #440).

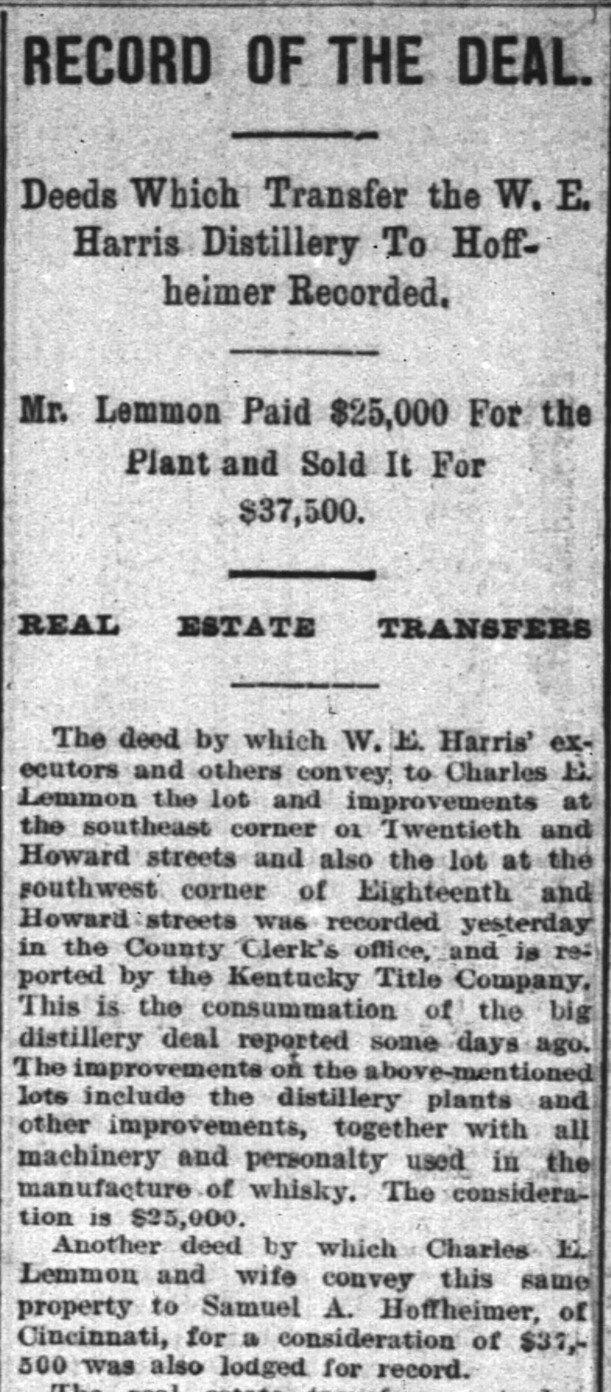

The White Mills Distillery was only a few blocks away from the Old Times Distillery. Both distillery properties had been owned by Charles E. Lemmon in the early 1890s. Almost immediately after purchasing the White Mills property (known as the W.S. Harris Distillery at the time) in 1894 for $25,000, Lemmon flipped the property, selling to Samuel A. Hoffheimer for $37,500. The Hoffheimer Brothers of Cincinnati became associated with the Whiskey Trust in 1899, just as the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (ASMC) was establishing its combine of Kentucky distilleries (the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Co.). Their decision to build a second distillery (Lynndale) beside the White Mills plant was made to vastly increase their scale of production. Having a large-scale production facility would allow the Hoffheimer Brothers to secure an enviable position within the trade, especially as so many large facilities owned by the trust were edging out their competition. By 1908, when so many of Louisville’s plants had been shuttered by the trust, the White Hills and Lynndale facilities would be required to increase their output. Bigger was certainly better in the eyes of the trust, and the White Hills and Lynndale plants were well-positioned to carry the torch in Louisville.

A.J. Schreiner, Sr. spent the next decade working for the Hoffheimer Brothers. During that time, Margaret “Effie” Schreiner gave birth to the youngest of their six children. The Schreiner family’s children were reunited with their uncle J.J. and their new aunt, Rose, just as the future of their own father’s distilling career grew bleak. Though the evidence directly linking A.J., Sr. to distilling or yeasting operations at White Mills Distillery are informal at best, there’s no doubt that he gained a great deal of experience as a distiller before the Food & Fuel Act of 1917 shut down America’s distilleries before the First World War. A.J., Sr. would have accumulated a great deal of industry experience in all aspects of the distilling trade, but he also would have lost the ability to work as a distiller in Louisville. Times were changing, and the family was forced to adapt.

It’s important to note here that 1917 not only marked the end of whiskey production for almost every distillery in the United States, but the war effort also marked a large shift in the mood of Cincinnati’s whiskey industry. America’s distilling companies were going up for sale, and Cincinnati’s whiskey men were buying. Cincinnati’s whiskey men controlled the largest distribution networks in the country, and with that control, they would become America’s power brokers within the whiskey industry going forward. Lewis Rosenstiel and Lester Jacobi would assume leadership positions in Cincinnati as partners in the Cincinnati Distribution Company. Rosenstiel and Jacobi would cement their ties to the American Spirits Manufacturing Company through their association with Daniel W. Weiskopf’s Republic Distributing Company, as well. These partnerships were formed with a mutual interest in consolidating America’s whiskey stocks. Distillers that had connections to the companies these distribution networks purchased would hold an advantage. Perhaps it was lucky that A.J. Schreiner was connected to the Hoffheimer brothers. The Hoffheimer brothers’ connection to Lew Rosenstiel and Lester Jacobi would certainly pay off in the years to come. Experienced distillers and yeast masters with connections to Cincinnati’s brokers would reap benefits, if only by being in the right place at the right time.

The United States entered the First World War in April 1917, and A.J.’s eldest sons were old enough to be eligible for the draft. 2 months after filling out his draft card, 22-year-old Fulton Leslie Schreiner suffered injuries in an automobile accident. His dislocated left hip and fractured right hip bone may have cost him his job at the Standard Oil Company where he worked and his eligibility for military service, but he would heal. The White Mills and Lynndale plants were forced to close, but the distillery’s warehouses remained active as consolidation warehouses. Fulton Schreiner was down, but not out. The White Mills Distillery property was sold in 1919 to its distillery’s manager, George Lee Redmond, and his investment partners, Oscar and Allen Hollenberg. It is possible that the now 53-year-old A.J. Schreiner, Sr. remained in Louisville working for Redmon, but it’s unclear what those first few years of Prohibition meant for him and his family.

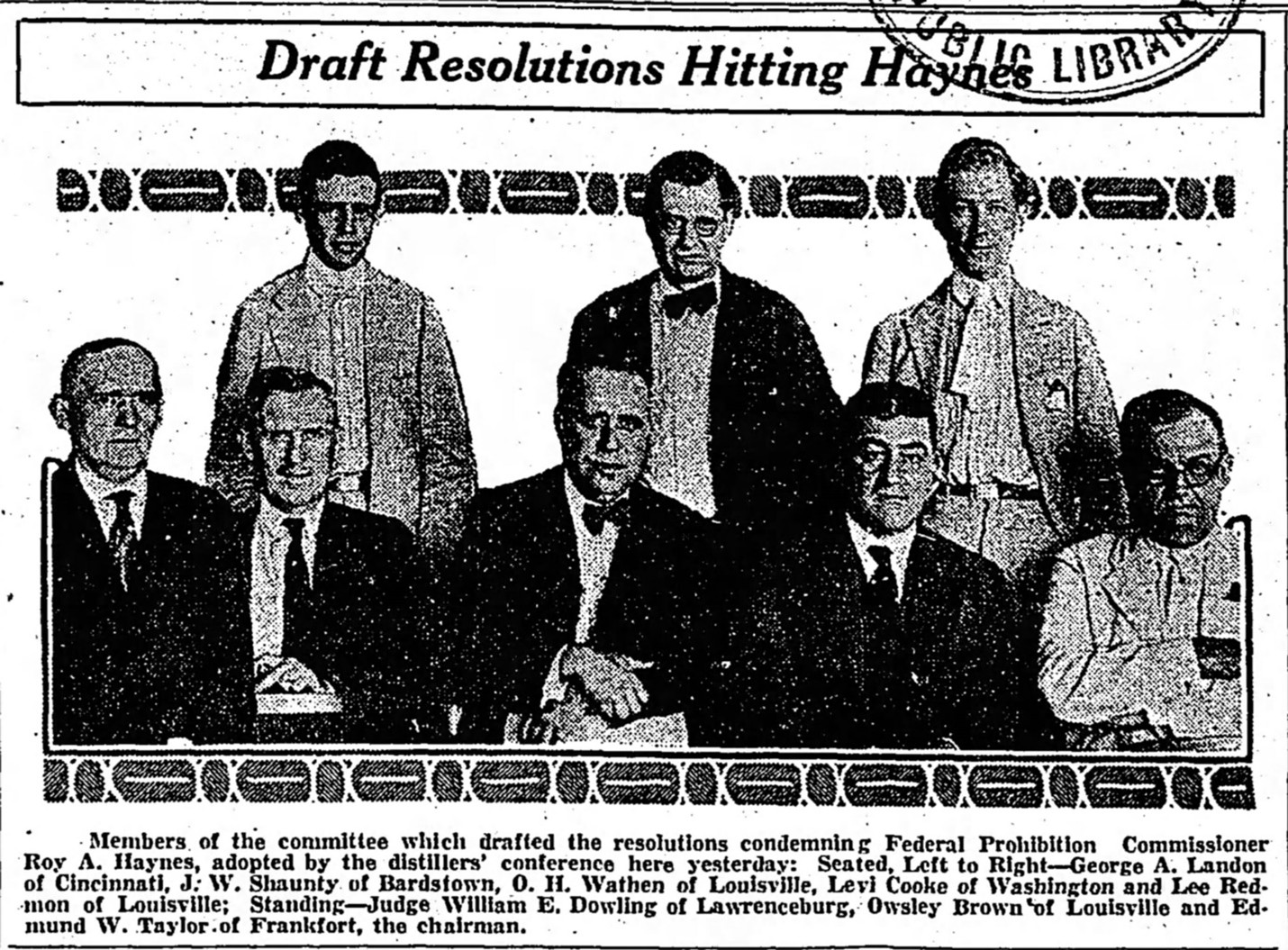

By 1922, a small group of Kentucky warehouse owners and lawyers petitioned President Harding, his Secretary of the Treasury, Andrew Mellon, and the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, David Hunt Blair. They sought to curtail the illegal activities of the Federal Prohibition Commission and its leader, Roy A. Haynes. The warehouse owners argued that Prohibition agents were overstepping their job requirements by harassing the legal activity in medicinal trade that they were conducting. G. Lee Redmon was among the consolidation warehouse owners that fought to retain the legal right to trade in medicinal whiskey. Their licensed businesses were experiencing harassment under Commissioner Haynes watch, they argued, and the powerful whiskey men in Louisville were having none of it.

Through their petitioning, the Kentucky-based warehousemen also sought to gain preferential treatment for their consolidation warehouses, and they would receive it in the form of the Warehouse Concentration Act of 1922. G. Lee Redmon was granted one of 26-30 licenses which allowed warehouse owners to store and safeguard the nation’s medicinal whiskey stocks. Over 300 of the nation’s remaining distillery warehouses (down from over 800 in 1917) would be emptied, and their contents would be relocated to one of those limited-licensed facilities. Redmon partnered with the Dant family in 1923 to expand their ownership stake in his warehouse’s contents. Any privately-owned barrels stored within the Redmon warehouse with any overdue storage payments or fees were soon publicly advertised as optioned for auction. G. Lee Redmon Co., Inc., just as every other American concentration warehouse owner contrived to do, bought up every barrel they auctioned for sale. The men eligible to buy these stocks were obviously limited to the men that were legally within their rights to sell it, so the auctions were not exactly open to the public. America’s whiskey, under order of the U.S. government, fell into the hands of the wealthy men that sought to control its storage. In other words, the men that controlled the country’s concentration warehouses now controlled the future of America’s mature whiskey stocks during (and after) Prohibition. Being an employee of a company that owned a concentration warehouse was an immediate advantage to a distiller or a warehouseman that worked for them. Whether A.J. Schreiner Sr. remained with G. Lee Redmon or not, he would soon find new employment. His reassignment, however, would not be outside of the sphere of influence he now found himself within.

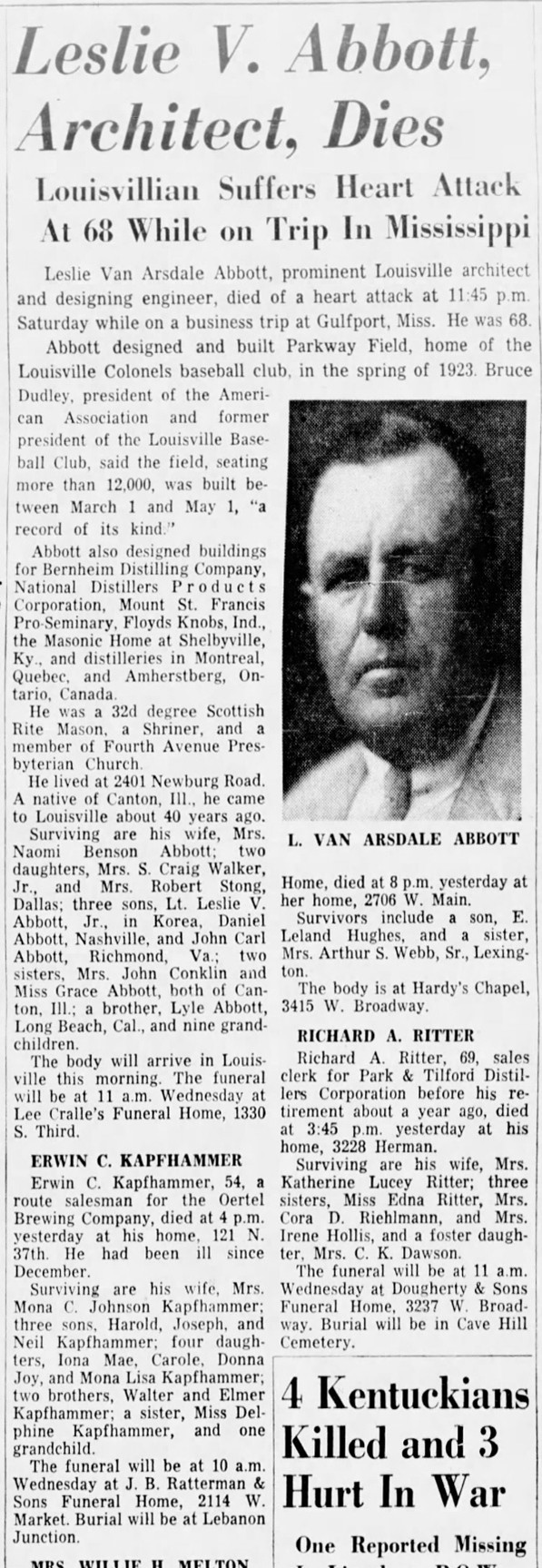

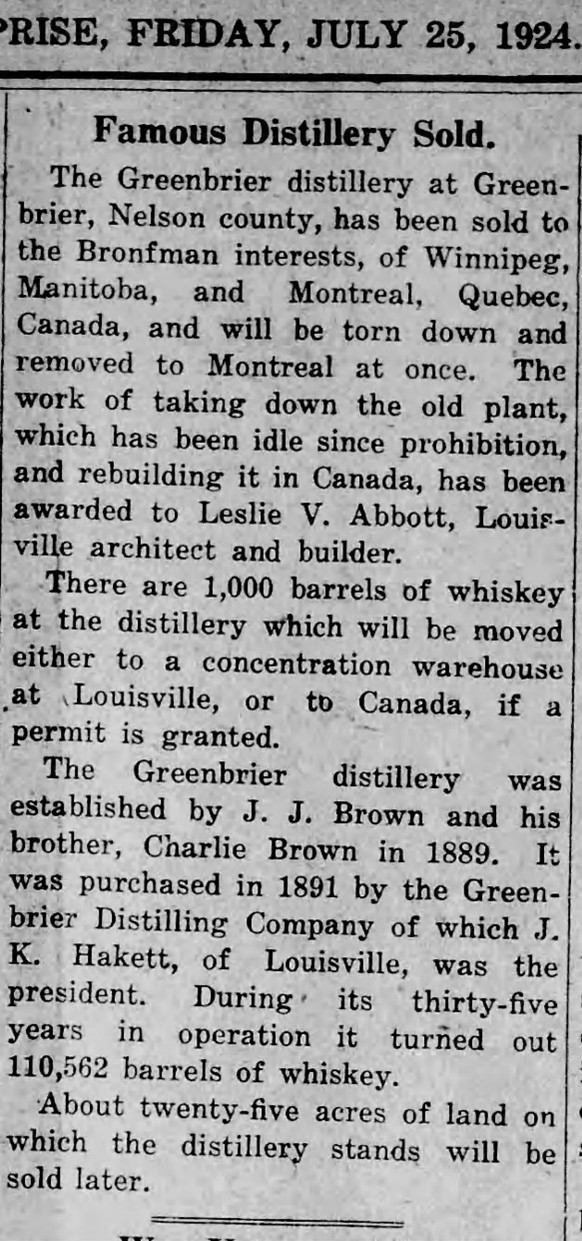

By the mid-1920s, A.J. Schreiner was shifting gears again. His next move was to Montreal, Canada to take on work for the Bronfman brothers. Congressional testimony given by Henry H. Smith the week after Repeal (December 1933) explained that A.J. Schreiner and his son, Fulton, had been working for “Canadian Distillery, Ltd.”(sic) for 9 years. (H.H. Smith misspoke- he meant Sam Bronfman’s Distillers Corporation, Ltd., which was created to mimic Scotch whiskey’s Distillers Company, Ltd., aka DCL.) It does not say that A.J. was employed as head-distiller for all nine of those years, but A.J., Sr. certainly earned that title during his tenure there. The Congressional testimony places A.J., Sr. in Montreal in 1924. This timeline syncs with the purchase of Kentucky’s Greenbrier Distillery by Sam and Harry Bronfman, owners of Seagram’s Distilling Co., who had been operating as international liquor distributors/exporters of whiskey at the time. The whiskey belonging to Kentucky’s Greenbriar Distillery was shipped to a concentration warehouse in Louisville while the machinery and equipment from the plant were dismantled and shipped to Canada. Who better to oversee the installation and rebuilding of the distillery for Seagram’s than A.J. Schreiner? Newspaper articles revealed that the rebuild was assigned to a Louisville architect named Leslie V. Abbott, but Abbott would be connected to construction work being done on almost every plant the Schreiners were ever associated with during and after Prohibition! There is no doubt that the two men knew one another and worked alongside one another.

Once the Greenbrier Distillery was rebuilt in Montreal, the newly rebuilt plant became known as the LaSalle Distillery. Sam Bronfman, who had been a liquor dealer and exporter, knew very little about distilling. With the help of Kentucky’s William F. Knebelkamp and architect and engineer, Leslie V. Abbott, he would learn.* While A.J. Schreiner’s name does not appear in direct connection with these men in historic references, lines can easily be drawn between them.

William F. Knebelkamp was an avid horseman, a sportsman (baseball), and had been working for the Wathen family since he was a child. Before the 18th amendment went into effect in 1920, the R.E. Wathen Distillery was being transformed into a flour mill, and its plant manager, 47-year-old Knebelkamp, was supposedly finding a new career. In January 1919, Knebelcamp purchased controlling interest in the Louisville Colonels baseball team from Otho Hill Wathen, effectively making him the team’s new owner/manager. From the perspective of anyone paying attention, Wathen was leaving the whiskey industry to focus on flour milling while passing his sports team ownership to an ex-employee. The following year, however, both William F. Knebelcamp and Col. Otho H. Wathen were caught up in a highly publicized trial for illegally selling 120 cases of Wathen whiskey for $14,400 cash. The sale and illegal payments had taken place between January 2nd and 13th in 1919, just as Knebelcamp was supposedly abandoning his distilling ambitions to begin his baseball career. The charges against Wathen and Knebelcamp were eventually dropped, but the Wathens would continue to involve themselves in bootlegging schemes throughout Prohibition.

It appears that Will Knebelcamp went to Canada to set up the LaSalle Distillery for Bronfman, but he would return to Kentucky in 1927 to take on the role of head distiller at the Bernheim Distillery, just after that distillery had been sold to the Schenley Products Company. Just as Knebelcamp was moving back to Kentucky, A.J. Schreiner was recorded as having purchased a residential property in LaSalle, Montreal. A.J. Schreiner’s purchase likely indicates that he was moving to LaSalle to take on a more permanent distilling position at the LaSalle Distillery. Leslie V. Abbott, the Louisville architect hired to move the LaSalle Distillery from Kentucky, would likely have crossed paths with Schreiner at some point, as well. Even if they didn’t know one another personally, they had each been involved with the Kentucky Warehouse and Distilleries Company (Whiskey Trust) in one way or another. Though most references don’t specifically mention A.J. Schreiner, Sr.’s name as helping to establish the LaSalle Distillery, there’s little doubt he was involved. As far as A.J’s connection to Sam Bronfman was concerned, we’ll have to return to Louisville and the illegal liquor trade during Prohibition to make those connections. The Bronfmans were notoriously connected to illicit distilling, illegal exports, and several bootlegging gangsters throughout the 1920s and 30s.

Who was William F. Knebelkamp?

There were few distillers that managed to keep their jobs as head distillers during Prohibition and even fewer that managed to hang on to those jobs after Repeal. One such man was William F. Knebelkamp.

William Knebelkamp began to work at the age of 14, driving a milk wagon for his father’s dairy. In his very early 20s, he got a job working at the J.B. Wathen Distillery in Lebanon, KY. This was in 1892 when the Whiskey Trust was building its strength and exerting its power within the industry. William would stay with the J.B. Wathen company until 1899, when the Whiskey Trust had begun buying up the majority of Kentucky’s bourbon distilleries to form the Kentucky Warehouse and Distilleries Company (a subsidiary of the American Spirits Manufacturing Company). William was then transferred to distill whiskey at the R.E. Wathen Distillery in Louisville instead. He had honed his craft over the years and become an indispensable member of the company, so his salary of $2 a day nearly tripled to $1000 a year with the move. That same year, William was married to Sofia Miller. She would soon give birth to their first son, whom they named Wathen.

Over the next 2 decades, Knebelkamp’s love for horses and baseball further endeared him to the Wathen family. In 1912, William began his career in the national world of baseball by purchasing an eighth share in the old Louisville Baseball Club. Otho Wathen, likely through Knebelkamp’s influence, bought the Louisville American Association Club (The Louisville Colonels) soon afterward. By 1919, Otho sold the ball club to William, making him a full owner. While he’d continue to successfully run his club, win pennants, and push for good behavior from his players and umpires, his career in distilling was far from over. Being quite familiar with cattle and dairy cows from his youth, he would maintain his own dairy farm and considered himself a farmer. All of the stillage from the R.E. Wathen Distillery went to feed his cows. He also managed his own private stable of 12 thoroughbred horses (Winona Farm), racing them at the Downs. But his association with the Wathens and with the Whiskey Trust would secure his position as a master distiller within the industry even as National Prohibition set in.

Before the 18th amendment went into effect, Knebelkamp found himself in hot water for the part he played in the illegal sale of whiskey. In January 1919, while the R.E. Wathen Distillery was being transformed into a flour mill, William F. Knebelcamp and Col. Otho H. Wathen were caught up in a highly publicized trial for illegally selling 120 cases of Wathen whiskey in exchange for $14,400 cash. The sale and illegal payments had taken place between January 2nd and 13th in 1919, just as Knebelcamp was embracing his new baseball career. The charges were eventually dropped, and Knebelkamp was made to pay a $5,000 fine, but the Wathens would continue to involve themselves in bootlegging schemes throughout Prohibition. Knebelcamp would officially remain with the Wathens in Louisville until 1922 but would be called on in 1924 to help move the Greenbrier Distillery from Kentucky (NOT the one in Tennessee!) to Montreal, Canada. Sam and Harry Bronfman had come to Kentucky to broker a deal with the Wathens and apparently, Knebelcamp was part of the deal to deconstruct and rebuild the plant. After setting up the LaSalle Distillery in Montreal for Bronfman in 1924 (and likely helping to run other distilling operations), he returned to Kentucky in 1927 to take on the role of head distiller at the Bernheim Distillery, owned by the American Spirits Manufacturing Co. The distillery needed to be made ready for the first runs of medicinal whiskey to be manufactured in Kentucky since 1917. Knebelkamp would make large investments in the American Medicinal Spirits Company (the new version of his old job) and would take on the role of supervising distiller across National Distillers’ portfolio of facilities after Repeal. Though William died shortly after Repeal in 1935, his son, Wathen, would go on to capably fill his shoes after his death.

It’s curious to note that Fulton L. Schreiner did not join his father in Montreal, Canada until the early 1930s, or at least, not officially. He had been living in Louisville during the 1920s with his wife, Lorane. In 1929, when Fulton was 32 years old, he was arrested for maintaining a horse betting parlor in his home. If he was not directly related to his uncle J.J.’s business with horses and racetracks, he was clearly influenced by his uncle’s connections. The 1930 census lists Fulton as a “taxi driver”, though his business activities were likely more nuanced than that. Newspaper reporters in Louisville noted that the police were concerned about the number of guests he was receiving and with how many cars were parked outside of his home at any given time. Fulton was arrested again in 1932 for running an off-track betting room out of his home. This arrest may have been the impetus behind Fulton joining his father in Canada. Fulton’s gambling activities between 1929 and 1932 coincided with the years that Louisville had begun distilling medicinal whiskey again. The city must have been abuzz with talk of repealing the 18th amendment. The future of distilling whiskey in the U.S. may have become a reality again, but the prospect of landing a job within the industry without experience and connections remained unlikely. Either Fulton actively sought work with his father, or A.J., Sr. sought to bring his son safely under his wing in anticipation of the opportunities that lay ahead. Montreal’s distilling industry changed in response to America’s National Prohibition almost immediately upon Repeal in 1933.

During those early years of Prohibition, A.J. Schreiner, Sr. spent a decent amount of time in LaSalle, Montreal, but he did remain there. Knebelcamp, who had also been part of the Greenbrier rebuild, returned to Kentucky in 1927 to repair the Bernheim Distillery in south Louisville. Knebelcamp, a loyal distiller for the Wathen family, would easily transition into his new leadership role as a distiller for the newly incorporated American Medicinal Spirits Company (AMSC). The Wathens and several other concentration warehouse owners had been successful in lobbying Washington in 1927 to allow their companies to manufacture medicinal whiskey once again. The Whiskey Trust, otherwise known as the American Spirits Manufacturing Company, immediately set to work to reorganize (and rebrand) their company as the American Medicinal Spirits Company. The Wathens brought Knebelcamp back into the fold and set him to work repairing their largest and most valuable distillery asset in Louisville. A.J. Schreiner, however, does not appear to have returned to Kentucky until Repeal.

There has been some interest in the idea of A.J. Schreiner possibly spent some time in Mexico during Prohibition. My personal opinion is that he never left Canada, mostly because he was busy buying a house in LaSalle, Ontario in 1927 while Joseph L. Beam was firing up the stills in Juarez. There is little proof one way or another, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. If he was sent, instead, from Canada, America’s neighbor to the North, to Mexico, America’s neighbor to the South, who sent him there?

The following is a digression, but the topic has plagued me for months. I hoped that I would find some proof of A.J. Schreiner, Sr. in Mexico, but my research has left me with nothing but loose ends. The following (in blue) provides some insight into how it may have happened. One 1938 article entitled from the If he did go to Mexico, it would have been in a supportive capacity, and he most likely would have been hired by Owsley Brown of the Brown-Forman Company. Even if Mr. Schreiner did not go to Mexico during Prohibition, the following insights help to explain a bit about why distillers like himself WERE sent there and how closely the Louisville-based distillers had become during the 1920s.

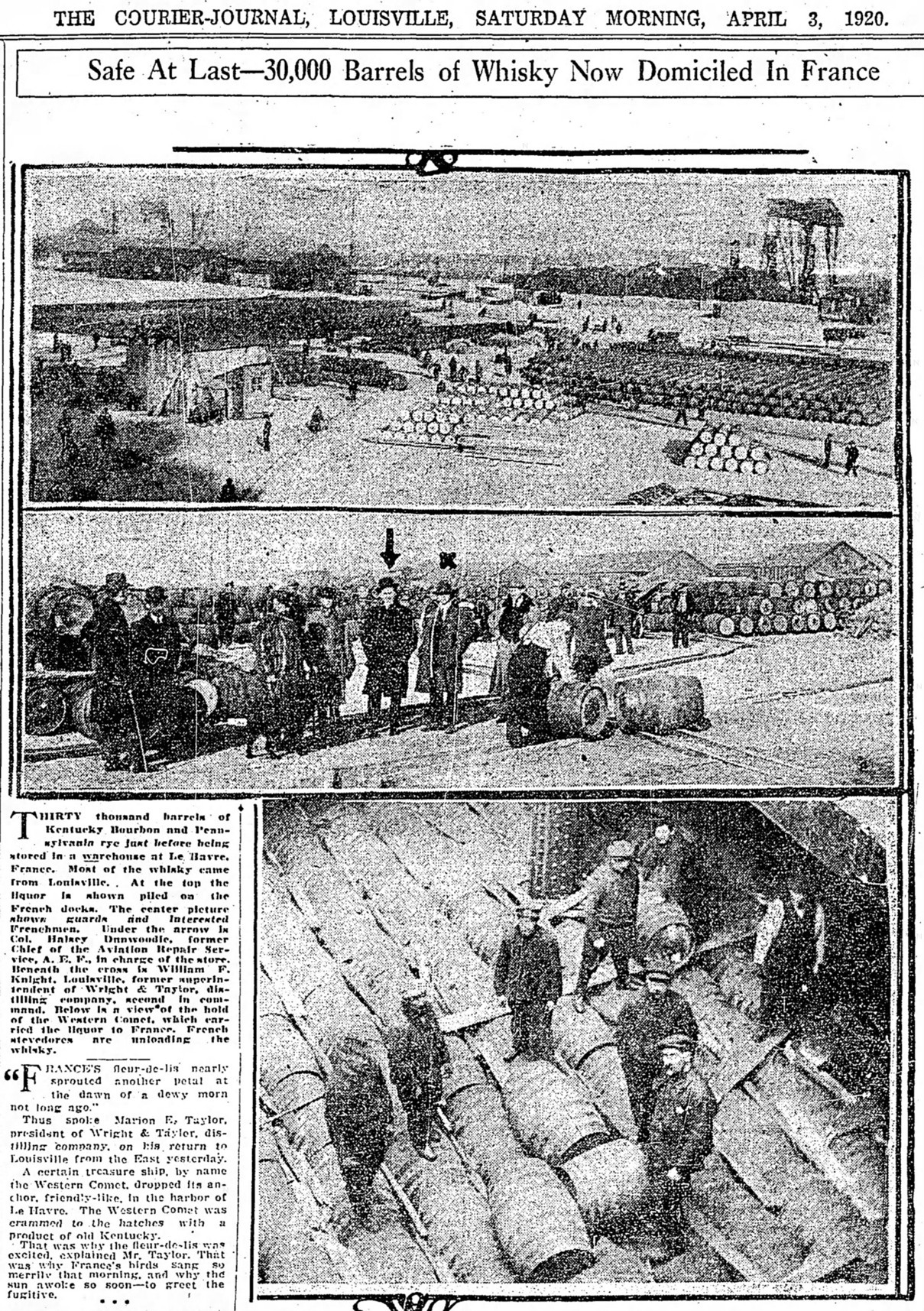

In 1924, the G. Lee Redmon concentration warehouse at White Mills was sold to Owsley Brown of the Brown-Forman Company. Owsley Brown, son of George Garvin Brown, had been working every angle available to him since the earliest days of Prohibition to secure the future of his company and its brands. One of his preservation tactics had been to export tens of thousands of whiskey barrels to France in 1920. He appealed to European investors to invest in the future of bourbon. Brown’s close connections to powerful men in the U.S. government helped him to expand his empire during a time when America’s liquor trade was walking that fine line between legal and illicit. If A.J. Schreiner, Sr. maintained his position within the company at White Mills’ warehouse into the early 1920s, his new employer would have been Mr. Owsley Brown.

It should be said that Owsley Brown’s Brown-Forman Company would not have enjoyed the same success without its purchase of the White Mill and Lynndale Distilleries in Louisville during Prohibition. Owsley Brown would never have had access to a concentration warehouse if it weren’t for the foresight of George Lee Redmon and his partners. Redmon, who had been manager of the White Mills plant before 1919, bought the majority stake in the property (his partners were Oscar and Albert Hollenberg) at a time when buying a distillery property seemed like a foolish decision. Redmon understood the value was in the warehouse full of medicinal whiskey and he knew that his investment would pay off. G. Lee Redmon’s brother would take on the role of tax commissioner for Bourbon County in 1920, and in 1922, Redmon secured one of ten permits issued in the state to operate a concentration warehouse. By then, Redmon had already earned over $300,000 on his investment, but his concentration warehouse permit made his White Mills property priceless. By 1923, The Dant family (J.B., Felix B., and S.J. Dant) bought a half interest in the property and became large stockholders. Brown-Forman would make G.Lee Redmon an even wealthier man when they bought the White Hill Distillery’s concentration warehouse in 1924. They did not, however, buy the distillery building! This is interesting to note because in 1929 when several Kentucky distilleries were given permits to begin distilling medicinal whiskey again, it was G.Lee Redmon’s company that secured the permit, not Brown-Forman. Owsley Brown would correct his short-sighted mistake by buying up the rest of the property in 1931 (after Redmon’s death). Brown-Forman’s location remains on the site of the White Mills and Lynndale Distilleries to this day- at 18th and Howard Streets in Louisville, KY.

The D.W Distillery in Juarez

The small whiskey distillery was built in May 1926. Its owners were Mary M. Dowling of Louisvillle, Antonio J. Bermudez, and Enrique Florez. The original investment of $100,000 was to build the plant and install the machinery which had been brought to Juarez from Kentucky. The pot stills were built by Vendome to replicate the exact still used at the old Waterfill and Frazier plant in Tyrone, KY. Another $250,000 was invested the following year to upgrade bottling and other equipment, as well as provide a ready-made stock of whiskey to jump start sales. The distillery’s first run was in early in 1927, producing 5500 24-bottle cases. D.W. Distillery swore that its product was being the same way as it had always been made in Kentucky since 1810, even bragging about their famed Kentucky distiller, Joseph L. Beam. Years later, the owners would explain that they “used the original formula developed by the founders” and felt a connection to those founders because “Waterfill and Frazier whiskey was born in 1810, the year Mexico began its struggle for independence.” A good marketing opportunity is never missed by whiskey makers, regardless of where it was made! It seems Mary Dowling’s choice to move her Kentucky distillery to Juarez was not only determined by northern Mexico’s dry climate and its ability to be bring whiskey to market more quickly, but that it would find a ready market already established by the D.M. Distillery. Even the name D.W. Distillery was strikingly close to “D.M.Distillery.” For Waterfill and Frazier’s new home, the “D” stood for Dowling and the “W” for Wohl, one of the American investors, but not one of the principal owners.

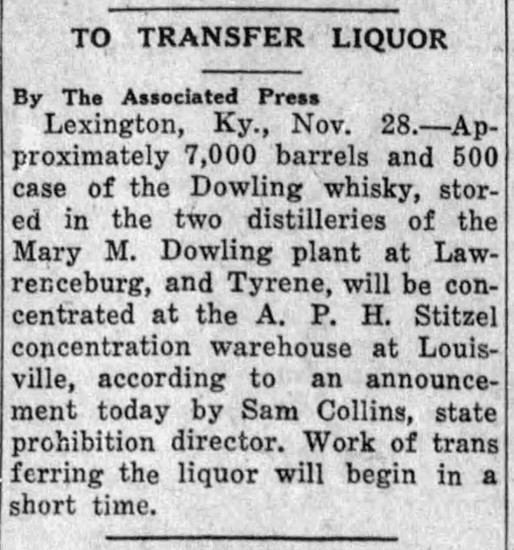

Mary Dowling built her D.W. Distillery just months after being found guilty of bootlegging. She had been caught selling whiskey out of her home in 1923, but the trial had finally come to its conclusion. She was fined $10,000 and her sons were sent to prison in March 1926. Construction of her plant in Jaurez, Mexico by the Waterfill & Frazier Company began in May of 1926. But Mary Dowling did not accomplish any of this on her own. The Dowling facility’s head distiller was famously known to be Mr. Joseph L. Beam. J.L. Beam had been trained as a distiller by his father, Joseph B. Beam and his uncle, John H. “Jack” Beam, founder of the Early Times Distillery near Bardstown (and one of the wealthiest men in Jefferson County before his death in 1915). Owsley Brown acquired the Early Times brand and late John H. (Jack) Beam’s whiskey in 1923, so his interest in hiring the distillers behind the whiskey in his Louisville warehouse made sense. While Jack Beam’s whiskey was being moved to G. Lee Redmon’s warehouse (White Mills), Mary Dowling’s whiskey was being moved to A. Ph. Stitzel’s concentration warehouse at Story Ave.

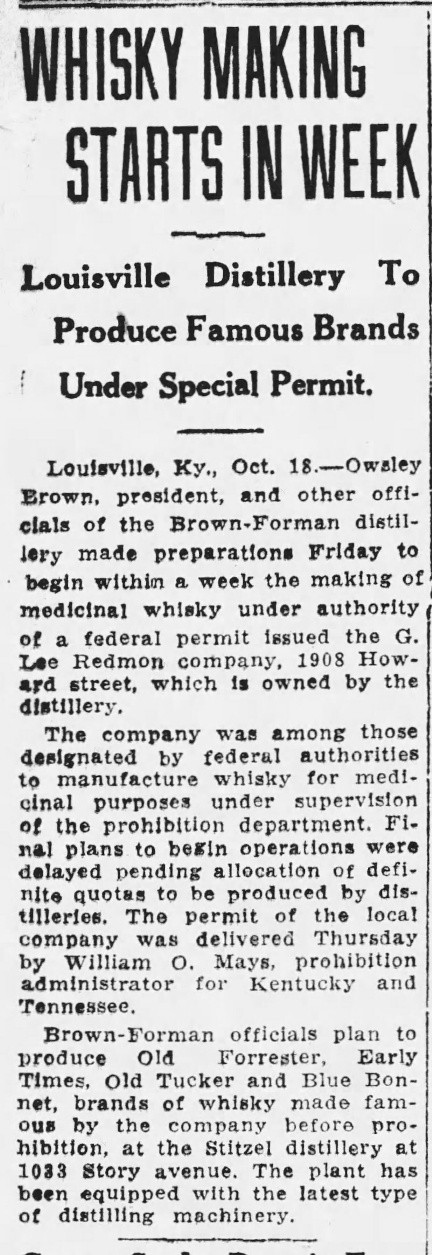

Louisville’s whiskey men (and woman) stuck together in their efforts to maintain their position within the industry. It helped that the government’s concentration warehouses blurred the lines between which company controlled the sale of which famous and sought-after brand. Joseph L. Beam was not only connected to the Dowling Distillery in Mexico, he was also connected to the Stitzel Distillery on Story Ave. When the Stitzel plant was brought back online in 1929, it was Joseph Beam and his sons that made it possible. The first whiskeys to be manufactured at the Stitzel plant for medicinal use were made specifically for Owsley Brown’s Brown-Forman and G. Lee Redmon companies, the Frankfort Distillery (previously the Paul Jones Co. until 1922), and A.Ph. Stitzel Co. While it may sound odd to say that these companies’ whiskeys were all being manufactured at the same plant in 1929, it’s not as strange when you realize that the companies were connected to one another. Arthur Philip Stitzel was the only one with an operable plant, so production was carried out at his distillery in Butchertown. When Prohibition ended and A.Ph. Stitzel built their new Stitzel-Weller plant in the Shively neighborhood of Louisville, Frankfort Distillery (with the help of Roy Beam) continued to operate the distillery on Story Ave. The fact that the distillers employed by any of these companies hopped from one company to another during and after Prohibition was not unusual once you realize they were sharing resources.

Mary Dowling’s whiskey was safely stored at the Stitzel Distillery while she set her sights on Mexico. A.J., Sr.’s connection to both the Old Times/Sunny Brook Distillery and the White Mills & Lynndale Distilleries would have made him an excellent choice to oversee the construction and setup of the plant with Joseph L. Beam. If he did go to Mexico, he would have held a supporting role in the project. He certainly had the decades of experience to make his appointment a successful one.

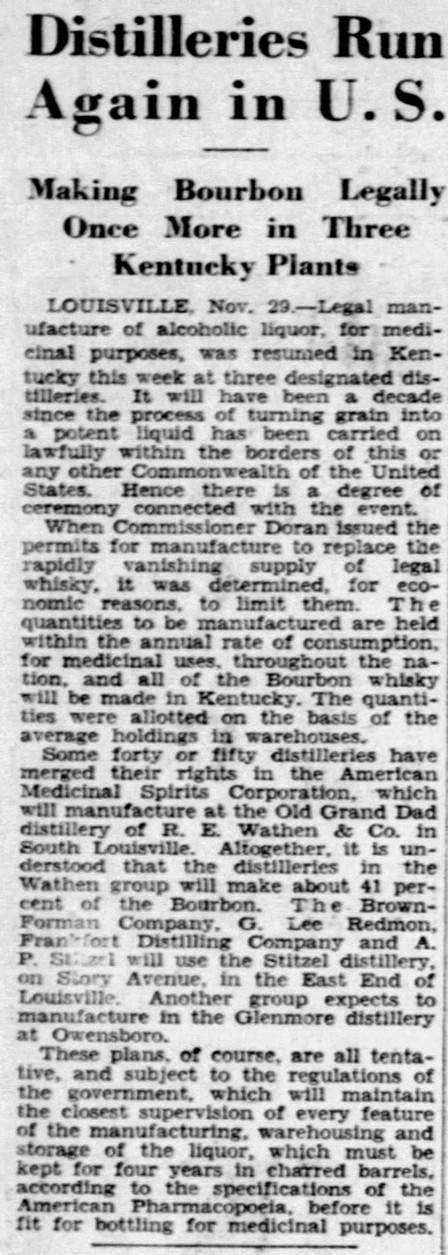

These articles, the first (Whiskey Making Starts in Week) printed in “The Owensboro Messenger” on 10/9/1929 and the second (Distilleries Run Again in US) in “The Windsor Star” on 11/29/1929, both help to explain the crossover and collaboration taking place between distilling companies in Louisville as distilleries began manufacturing whiskey again during Prohibition. A confusing element within the second article is the mention of the American Medicinal Spirits Company using “the Old Grand Dad distillery of R.E. Wathen” to distill its whiskeys in 1929. While R.E. Wathen did own the brand “Old Grand Dad”, the distillery being described in South Louisville was just south of the Bernheim Distillery along the Illinois Central Railroad line.

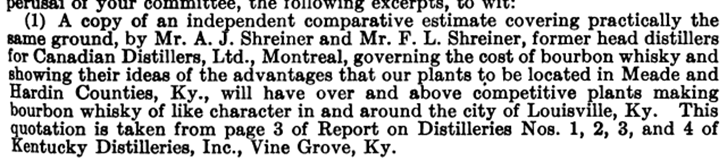

A.J. Schreiner, Sr.’s complete grasp of the industry and the inner workings of a distillery landed him a secure job and the opportunity for promotions within the Seagram’s company.** A.J. Schriener and his eldest son, Fulton, were well-positioned at the LaSalle Distillery in the early 1930s. As the Repeal of Prohibition grew closer, however, the dynamic between Canada’s whiskey producers and American consumers began to change. Andrew and his sons would have seek new opportunities. In 1933, A.J., Sr. and his son, Fulton provided the following estimates for Harvey H. Smith, a Kentucky lawyer (later a judge), looking to prove how much more cost effective smaller distilleries could be over the larger firms attempting to monopolize the industry. The Schreiner men’s expert opinions were shared with the Congressional Ways and Means Committee in December 1933:

Harvey H. Smith became known for his accusations against the Whiskey Trust in Kentucky based on his testimony before Congress in Dec 1933. The four plants he described were never completed, though a great deal of investment dollars went into trying to get them built. By 1936, Harvey H. Smith was promoting the construction of several new companies he formed with other investors. The group of four distilling companies he claimed to represent were the O’Flarity Distillers, Inc., the Old Blue Ribbon Distilling Co., and Old Woods Distilling Co., and the Lincoln Springs Distillery, all in Kentucky. Smith had plans to build 100 barrel-a-day distilleries in Vine Grove and in Warsaw, Kentucky. By 1939, however, his charter had been revoked. The letter implies that A.J. Schreiner and Fulton were approached to act as distillers for the company, but nothing came of it.

**It’s interesting to note that Bronfman’s company in Montreal was called the Distillers Corporation, Inc., but Harvey H. Smith states very clearly in his 1933 Congressional testimony that his company’s distiller (he was describing A.J. Schreiner, Sr.) had been head distiller for Canadian Distillers, Ltd. And that he had been in Canada for 9 years. While this may simply be a mistake, it’s more likely that he was describing A.J. Sr.’s distilling role after 1927.

After 1933, A.J. Schreiner is often described as having been with the Schenley Distilling Company and its predecessors for decades, but that’s not entirely accurate. During the 1920s, Canadian Distilleries, Inc. described the company controlling the Corbyville Distillery in Ontario. Canada’s own Prohibition laws were not lifted in Ontario until 1927, around the time that Schreiner moved to Montreal. The owner of the Corbyville Distillery in 1927 was Mortimer Davis, but Davis had been working with Harry Hatch (of Hiram Walker Gooderham & Worts fame) from 1921-1923 to popularize his Corby’s Canadian Whisky with the bootleggers and rumrunners moving product into the US. Once Prohibition lifted in Ontario, it’s likely that there was a great deal of trading and crossover between Davis and the Bronfmans. The bottle below lists the distillery as Consolidated Distilleries Ltd. (with offices in Montreal) which was a subsidiary of the Canadian Industrial Alcohol Company, Ltd. Both companies were involved in a merger acquisition by Bronfman’s Distiller’s Corporation, Inc. in 1929. There was clearly plenty of crossover through the bootlegging trade, so the association made by Harvey H. Smith between the Canadian Distilleries, Ltd. and the Montreal-based Bronfman brothers was likely NOT arbitrary.

(For information on the history of these plants, see my full write up on Lawrenceburg’s historic plants at Facebook.com/AmericanWhiskeyHistory)

After acquiring the Squibb Distillery, Schenley went straight to work upgrading and enhancing their new plants. Now renamed the “Old Quaker Distillery”, the site would receive a million-dollar makeover and be ready to fill 500 barrels a day by early November, even before Repeal took effect. They hired Frank Messer & Son of Cincinnati as contractors for the project. Flood lights at the site allowed work to carry on day and night. Schenley’s distillery site in Schenley/Aladdin, Pennsylvania, which had already been improved during Prohibition from 100 barrels a day to 350 would be stepped up again to 500 barrels a day. The George T. Stagg Distillery would go from 100 barrels to 350 barrels per day. Schenley made another acquisition of the James E. Pepper Distillery in 1934, but that plant would remain idle, serving instead as a storage facility for its whiskey stocks. James E. Pepper was not brought back for production purposes.

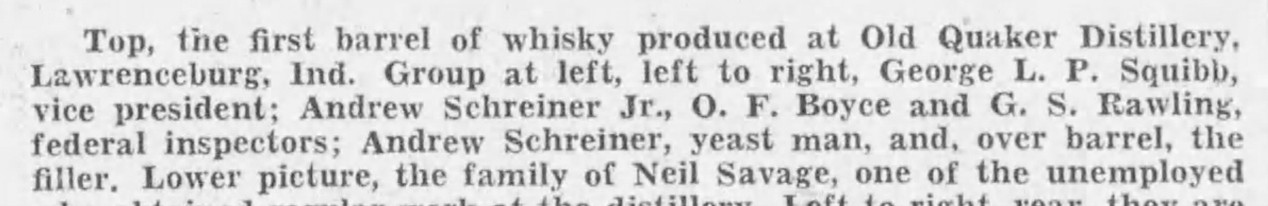

Three months before the renovations were complete at Old Quaker Distillery and days before Repeal Day, the plant’s stills were fired up. The first whiskey to be drawn off the still at Old Quaker- the first in 16 years on the old Squibb property- took place the morning of December 3, 1933. George P. Squibb, vice president of the new company, was acting manager of the plant with Robert Squibb in charge of the cistern room. A.J. Schreiner, now 65 years old, was hired by Lester E. Jacobi as yeast master for the plant. While it might seem odd that a Seagram’s employee suddenly took work on with Schenley, it’s not so farfetched. Sam Bronfman and Lew Rosenstiel were very friendly with one another…until they weren’t. A.J., Sr’s younger brother, J.J. Schriener (62 years old), was brought on to manage production of gin at both the Old Quaker in Indiana and the Schenley plant in Pennsylvania. A.J. Schreiner, Jr. was brought on to assist his father and uncle, as well. The Schreiner family’s connections to Cincinnati men had officially paid off. A.J. Sr. was described in newspapers as having been with Schenley for 40 years when he took his role at Old Quaker, but, as we’ve discussed, that was not entirely true. Schenley Products Company, which was incorporated as the Schenley Distilling Company in 1933, had only been associated with Lew Rosenstiel and his Cincinnati firms since 1920 when it was founded. A.J. Schreiner’s connection to Cincinnati was, indeed, 40 years old, but his connection was complex and nuanced, as most distilling connections tend to be.

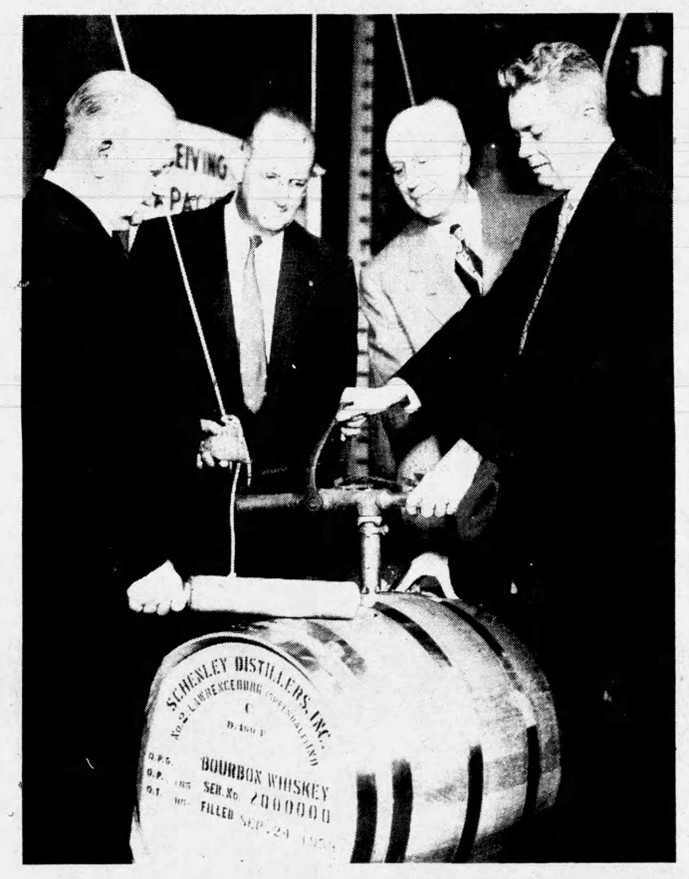

The photo above, from the Cincinnati Post, published on Repeal Day (December 5, 1933) shows A.J. Schreiner, Sr. and A.J. Schreiner, Jr., both standing behind the first barrel filled at Old Quaker Distillery in Lawrenceburg, Indiana. The whiskey, which had been manufactured 2 days earlier, prompted a lawsuit against the company. While the lawsuit was quickly dismissed once the company proved their legal right to distill “during Prohibition”, it signaled a dynamic shift in the whiskey industry. Whiskey was back, and the Schreiners were not only part of its return, but they’d also been part of its preservation over the last 13 years.

In 1935, A.J. Schreiner, Sr. became a controlling officer within the Schenley Distillers Corporation. Schenley was creating their new subsidiary, the Old Quaker Company, and kept Lester E. Jacobi on as the company’s president. It was Lester Jacobi’s decision to hire A.J., Sr. as yeast master when Old Quaker was formed just before Repeal. He would have been very familiar with Mr. Schreiner’s resume connecting him to Cincinnati’s Hoffheimer Bros. and to their network of Cincinnati businesses. Robert Nanz, who had been hired as manager of the Old Quaker plant, was named vice president, and A.J. Schreiner Sr. was named secretary/treasurer. The distillery, which had been slated to double in capacity, would become the second largest distillery in the world! The expansion of the plant was overseen by Carl J. Keifer, consulting engineer for Schenley. Its capacity would double, yet again, to 1150 barrels per day (57,500 gallons daily). A $300,000 warehouse would be built to house 100,000 barrels. As if the expansion of Old Quaker in Lawrenceburg wasn’t enough, Schenley began a lease on the old distillery at Terre Haute. The leased facility would be known as “Old Quaker Company, Unit No. 2.” The sky seemed to be the limit for Schenley as Lew Rosenstiel launched a huge ad campaign promoting Schenley and Old Quaker’s brands. A.J. Schreiner was lauded as being among the lead members of Schenley’s team- “the Cream of the Country’s Distillers.”

In 1936, Lutz Frederick Schreiner, A.J. Schreiner Sr.’s youngest son, was transferred to Schenley’s James E. Pepper Distillery in Lexington, KY to manage Schenley’s warehouse there. Unfortunately, just as Lutz was being transferred to the Pepper Distillery, A.J., Sr. became ill and was sent to the hospital. After several weeks, A.J. Schreiner, Sr. was removed from the hospital and transferred to the calm and comfort of his eldest child’s home. Ethel (Schreiner) Brawand and her husband, Albert, nursed Mr. Schreiner in their home on Oakley Avenue in Greendale, a neighborhood in Lawrenceburg, Indiana, during his final days. (Greendale is the neighborhood where the Old Quaker/Squibb Distillery was located.) Andrew Joseph Schreiner, Sr. died on April 4, 1936, at the age of 69.

While Andrew Schreiner had only been associated with the Old Quaker Distillery for three years, his career in distilling spanned over half a century. His experiences as a distiller connected him to whiskey-making traditions (bourbon and rye) in Kentucky, rye whiskey-making techniques in Pennsylvania, and even included international influences through his work in Canada and Mexico. He was one of the few American distillers able to claim such a broad span of expertise. A.J. Schriener, Sr. was often described as “a man who made more whiskey than any man living”. That phrase may have been a common marketing claim for many of America’s aging distillers, but A.J., Sr.’s extensive career was unique and prolific. His enviable resume would place him among the industry’s most knowledgeable and well-rounded practical distilling experts to have survived Prohibition. A.J. Sr.’s sons not only benefitted from that expertise, they thrived on their father’s contributions, before and after his passing.

The years after Repeal sent the Schreiner men in different directions. While A.J. Sr., A.J. Jr., and Lutz Schreiner had been busy operating the Old Quaker plant in Indiana after Repeal, the rest of the Schreiner family’s distillers had been employed elsewhere. Fulton L. Schreiner, though he had been living in Louisville during Prohibition years, left Kentucky to join his father in Canada in 1932. When his father returned to Kentucky, Fulton went to work for Harry Bronfman and Seagram’s at their plant in Vancouver, British Columbia. It may be that his father’s death brought Fulton back to the U.S., however, because he is noted in the Lawrenceburg Press as living in Belle Meade, Virginia in September 1936. The Belle Meade Products Company had been incorporated in 1934, but the US Census reveals that Fulton had been living in Louisville in April 1935, so his relocation to Virginia would have taken place sometime after that. The 1940 census for Fauquier County, Virginia reveals that Fulton’s sons Joseph and Kenneth had also taken positions with their father at the Belle Meade Distillery. Joseph was listed as “fermentologist” (yeast) and Kenneth as “distilleryman”. Andrew J. Schreiner’s youngest son, A.J., Jr., however, would follow most closely in his father’s footsteps.

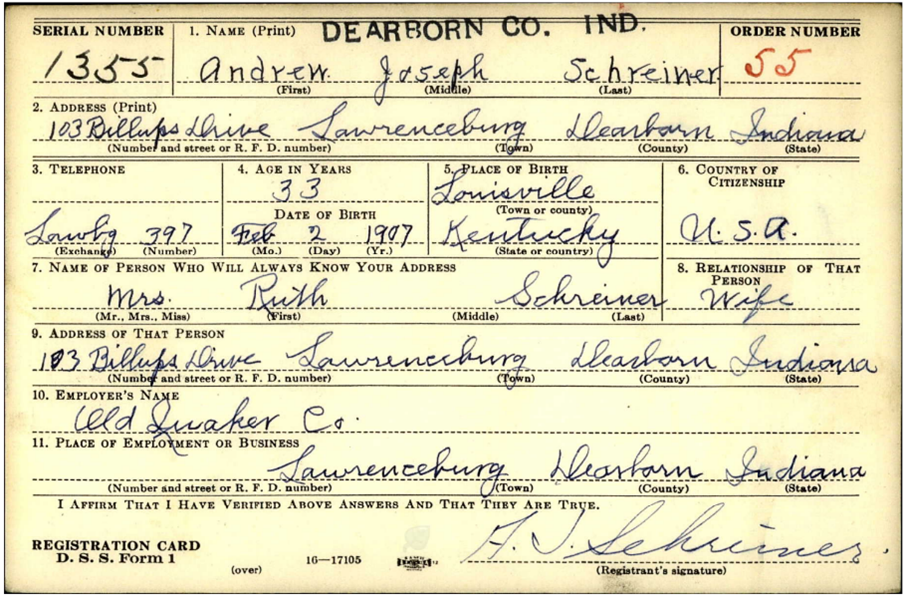

An article published in 1938 titled “Three Distillers” describes A.J. Schreiner, Jr. as his father’s protégé. It explains that A.J., Jr. accompanied his father and older brother, Fulton, to Montreal, Canada before taking a position with the Bernheim Company after Repeal. (This distillery is completely unrelated to “Bernheim” as we think of it today, which was rebuilt by Heaven Hill in 1996 after their devastating fire in Bardstown.) The American Medicinal Spirits Manufacturing Company’s Bernheim Lane plant was the first distillery to fire up its stills in 1929 (at least in Kentucky), two weeks prior to A. Ph. Stitzel’s Story Ave plant. (It is unclear if the AMSC plant described was the Bernheim plant or the R.E. Wathen plant just below it. See figure 9.) Almost immediately, the distillery was able to produce 165 barrels per day. (The following year, the AMSC was also manufacturing about 700,000 gallons of rye whiskey at their plant in Baltimore. The third to begin manufacturing in 1929 was the Glenmore Distillery in Owensboro.) The “Three Distillers” article described A.J., Jr. as returning to Louisville in 1933, years after the Bernheim Company began production under the watchful eye of William Knebelcamp. A.J. Jr’s wife, Ruth Elizabeth (Vardeman), had just given birth to their son, Andrew J. Schreiner III, in April 1933, so it was only natural for him to want to return to Louisville to be near family and friends. When little Andrew was 6 months old, the distiller moved his young family to Lawrenceburg, Indiana.

When Andrew J. Schreiner, Sr. died in 1936, A.J. Jr. was called upon to take his father’s place in Lawrenceburg at the Old Quaker plant. He was 29 years old and nervous about taking on the demanding leadership position, but he had been distilling with his father since he was 17 and was certainly up to the task. It appears that Lutz Schreiner moved to Lawrenceburg to help A.J. at Old Quaker. Their older brother, Alvin, would remain at Schenley’s James E. Pepper facility in Lexington.

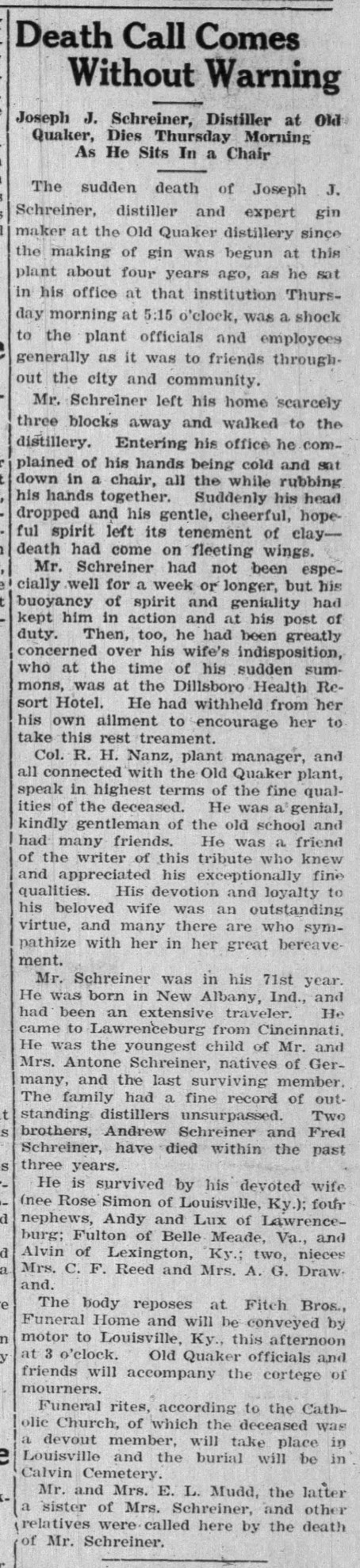

In February 1939, Joseph J. Schreiner died suddenly in his office at the Old Quaker Distillery. He was 71 years old. Joseph was the last of the Schreiners that had been born in Germany. The new generation would carry on their legacy. The younger Schreiners could not have known that later that year, their lives would be changed forever.

The Second World War broke out in Europe in September 1939. Though the U.S. would not join the war effort for another 2 years, the distilling industry would be heavily impacted. Prohibition was over and the whiskey industry was finally in recovery, but the war would quickly knock it back down again. The Old Quaker Distillery, because it had been manufacturing gin (under the direction of J.J. Schreiner) and neutral grains spirits for blending purposes, was already in a better position than most. It would make the transition necessary to manufacturing industrial alcohol for the war effort more easily than most. Unfortunately for A.J. Schreiner, Jr., he was not trained to run the new alcohol unit by his father or his uncle. He was forced to learn to manage the production of industrial alcohol for use in gunpowder on his own, even sleeping at the plant to make sure things ran as smoothly as possible.

When the war was over, Old Quaker Distillery got back to the work of making whiskey. A.J. Schreiner Jr. was “mashing in” 12,600 bushels of grain per day. He was devoted to his job at the Lawrenceburg plant, even stopping in on Sundays to check in on the yeast. “I did it to ease my mind,” he was quoted as saying in 1988.

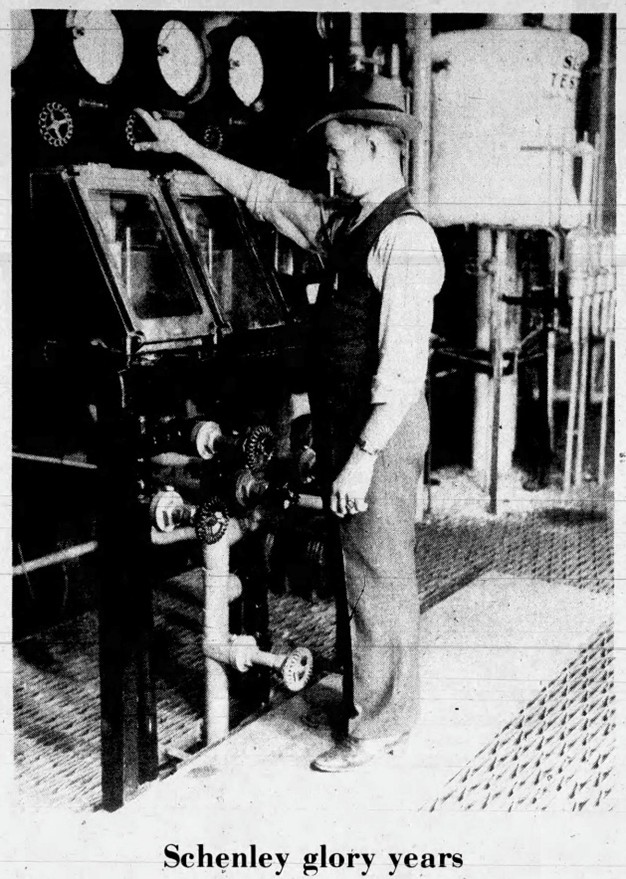

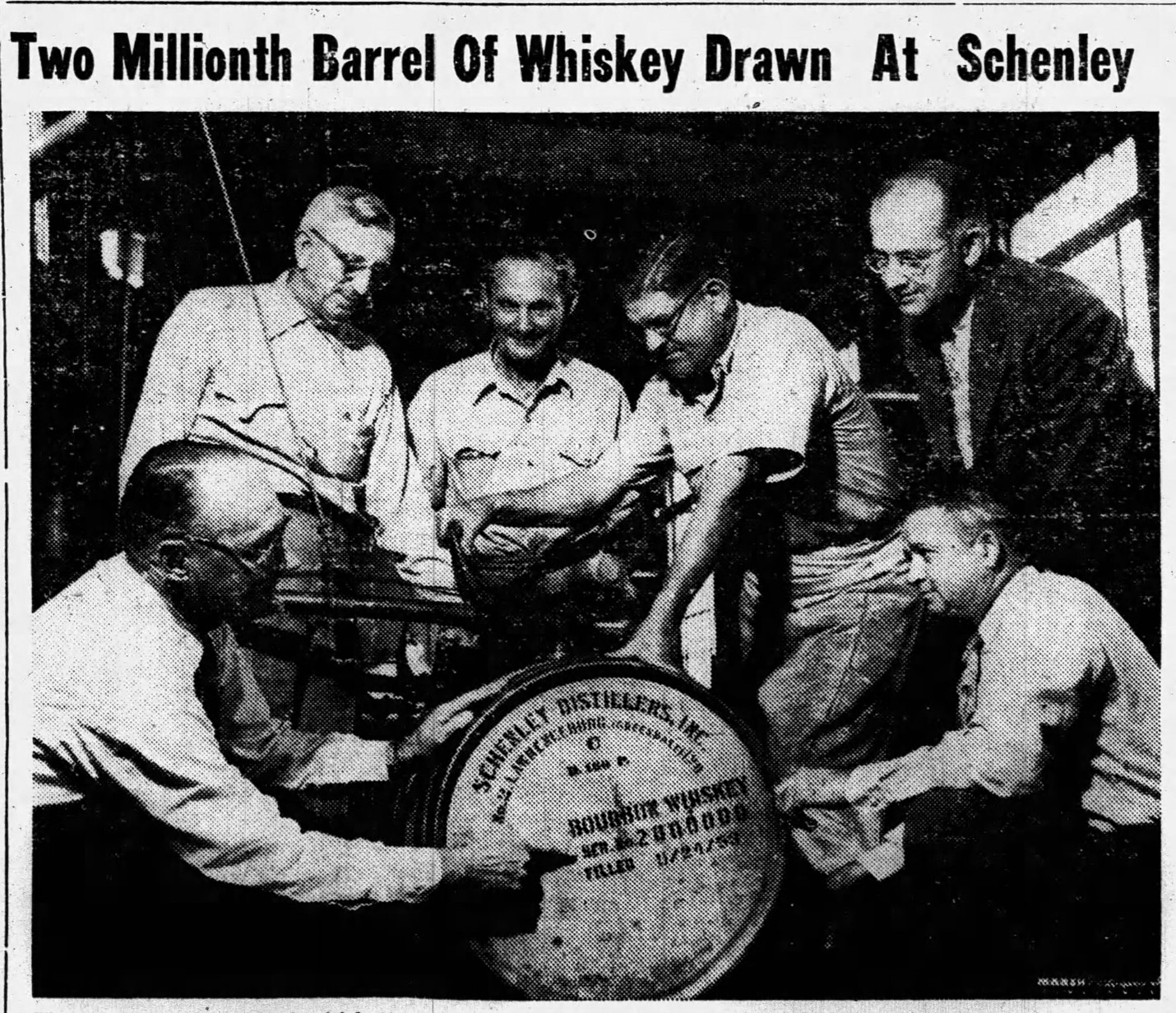

These images are from 1952. The first image shows A.J. Jr. adjusting knobs on the distillery’s spirit safe, conducting the flow of spirit. The second image shows (from left to right) Robert Nanz (retired vice-president of the company), Elmer J. Merkel (distillery manager), H.G. Morthorst (assistant regional tax commissioner for Cincinnati’s Alcohol & Tobacco Tax Division), and Edwards S. Monohan (president of the distillery). The men were filling Old Quaker’s 2 millionth barrel.

In 1962, Andrew J. Schreiner III joined his father at the Old Quaker Distillery. He had been living and attending school in Lawrenceburg since he was 6 months old. After graduating from Lawrenceburg High School, he attended the Kentucky Military Institute in Venice, Florida.

By 1959, 26-year-old Andrew III was employed by Schenley Industries at their bottling plant in Hialeah, Florida. By 1962, he was working with his father at Old Quaker. While not in the still house with his father, Andrew III was working in the distillery laboratory.

Andy Schreiner, Jr. remained with Schenley until his retirement in 1968. While he had been a distiller for over 44 years, he had been with Schenley for 36 of those years. He’d had a long career with the company, but it was time to move on. His son, Andrew Schreiner III, took his place at the distillery, but his work making whiskey would not last long. The plant ceased production of whiskey in 1969. Around the time of his retirement, A.J. Jr. was divorced from his wife, Ruth. On August 26, 1972, he married his second wife, Florence Kaiser. Florence had been working in the lab at Schenley since 1944. She finally retired after nearly 30 years with the company, in 1973. Even after his retirement, A.J., Jr. remained active as a distiller, stopping into J.T.S. Brown Distillery in Tyrone, KY twice a week. (That distillery today is known as Wild Turkey.)

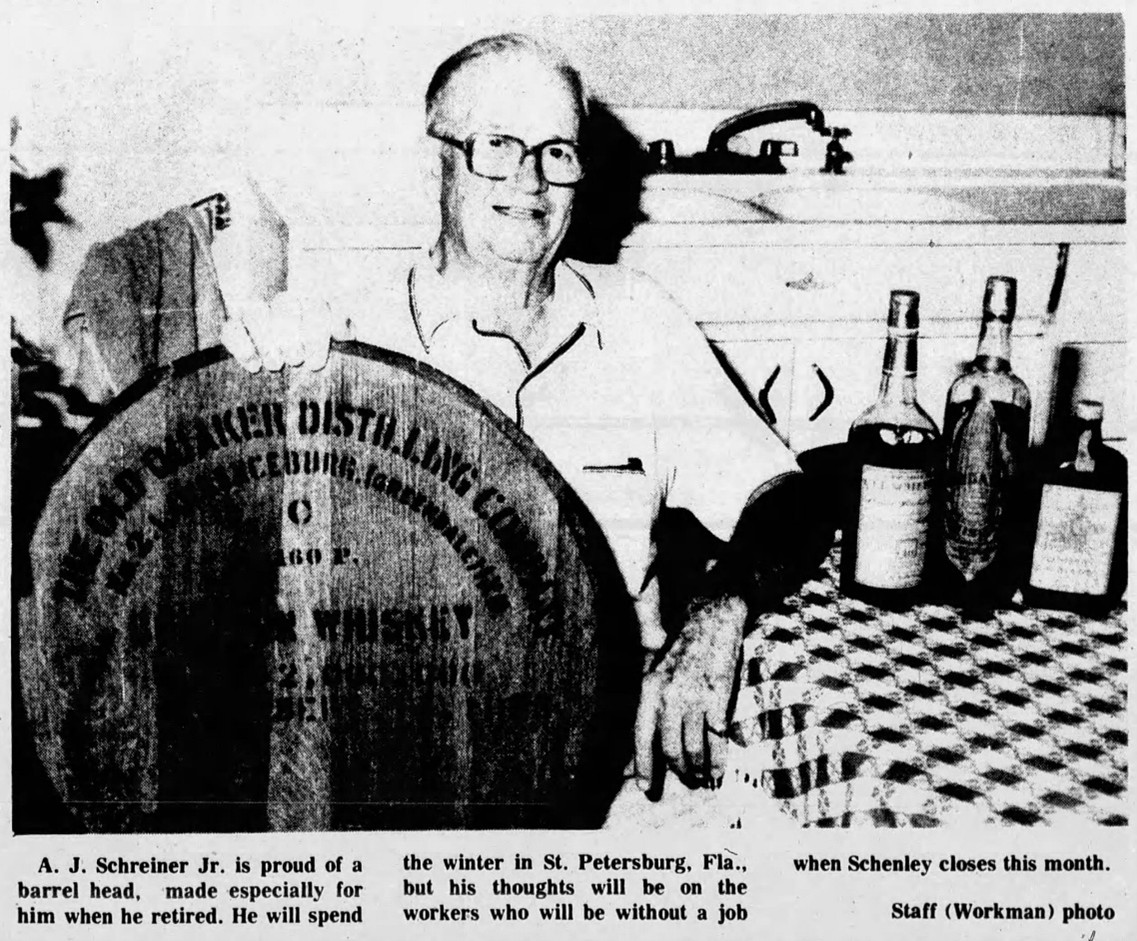

While no longer distilling whiskey, A.J. III remained working for Schenley in other capacities. In 1970, he went to Muscadine, Iowa to act as Alcohol Division Superintendent at Schenley’s Grain Processing Corporation. He spent over 25 years as manager of distilling, warehousing and processing. When the Old Quaker Distillery finally closed its doors in 1988, A.J. and his father were distraught, but accepting of the state of the industry. Times had changed.

Andrew Schreiner III went on to become president of the Lawrenceburg School District. He ran as a Democratic mayoral candidate in 1991. Ever the leader, in 1992, he defended his fellow ex-Schenley workers whose pensions had been bought out by a holding company.

Andrew J. Schreiner, Jr. passed away on November 11, 2003. He was 96 years old. The last surviving distiller from the Schreiner family, A.J. III, lived to be 80. He passed away in 2013, living long enough to see the distilling industry find new life. The Old Quaker plant where the family had spent so much of their lives, was long gone, but its neighbor, the old Seagram’s Rossville plant, otherwise known as Lawrenceburg Distillers Indiana, was bought out by Midwest Grain Products (MGP) in 2011. MGP was manufacturing rye and bourbon whiskeys for a new generation of whiskey bottlers. “Distilled in Indiana” had become a point of pride for distillery companies all over the country. Seagram’s distillers like Larry Ebersold and Greg Metze were building reputations within the industry. They would be hired as consultants for many young startup distilleries, bringing Indiana distilling know-how to the industry once again. In 2025, Larry Ebersold was inducted into the Kentucky Bourbon Hall of Fame, a first for Indiana’s distillers.

Today, the torch has been picked up by a new generation of the Schreiner family. Ken Schreiner and his wife, Maria, of Louisville, Kentucky have launched a new brand portfolio of spirits, each paying homage to Ken’s forefathers. Andrew J. Schreiner, Sr. is immortalized in a rye whiskey blend, made entirely from straight whiskeys manufactured in Indiana- by Indiana distillers. Their gin is named after Joseph J. Schreiner, gin distiller for Old Quaker Distillery. The future looks bright. No doubt, A.J. Schreiner, all three generations from 1866 to 2013, would be proud.