I felt a touch of autumn in the air this morning and my first thought was…pancakes with maple syrup. (And a giant cup of coffee!) I make my own maple syrup every year by tapping the sugar maples on my property, so it’s always a treat to have homemade pancakes with homemade maple syrup:) There is no doubt that my maple syrup is superior to anything I have ever bought in a store. And when it has finally finished boiling and is ready for bottling, it is one of the finest, liquid-gold taste experiences that nature has to offer. I don’t really have a sweet tooth, but maple syrup is not like a sugar-based syrup; It’s something else entirely. It has a darkly sweet character with peaks and valleys of rich, layered flavor. It makes you understand why someone might consider hugging a tree! There is nothing added- just pure tree sap, heat…and time.

The nuances that exist in my maple syrup always bring to mind the wide flavor variations that exist in craft spirits and the pride that must well up in a distiller when making their own small batch product from grain grown right down the road. Local climate variations and soil composition imbue unique characteristics in locally grown grain. The freshness of grain affects the quality of a whiskey mash. Fresh grain behaves differently and performs markedly better when it’s “mashed in.” When grain is dried and milled properly, it is ready for distilling right after harvest, in September or October- the start of the traditional rye whiskey distilling season. Today, bourbon season starts in July, but that’s a more modern contrivance based more on the availability of grain in the commodity market.

Historically speaking, apples were distilled first and while they were ripe in September and rye followed because it would keep through the winter. We are starting to see this pattern emerge again with small distillers who are often obligated to wait for the harvest when utilizing local grains. Small grains like rye, wheat, and barley are harvested a few months before corn. (Malting takes time as well, so that pushes the timeline back a bit, but not by much.) Market records from the 1800s show that new grain cost more than old grain (last season’s crop). Distillers were highly attuned to the quality of the grain they used just as chefs are very particular about their ingredients. The fact is that local means fresh and fresh means the potential for more flavor. Whether it’s maple syrup or rye whiskey, the effect on the finished product is undeniable. The finest quality products are made from fresh, locally sourced raw materials. All you have to do is taste the difference to know.

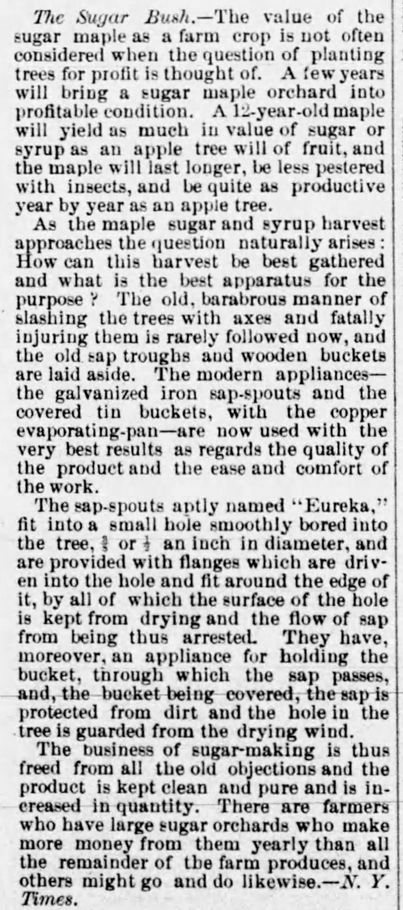

The article below, titled “The Sugar Bush”, was first published in the New York Times, but was reprinted in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania in 1885. It brings us from whiskey back to maple syrup and helps to illustrate how important sugar maple orchards had become and how much the value of maple syrup had grown in eastern markets during the late 1800s.

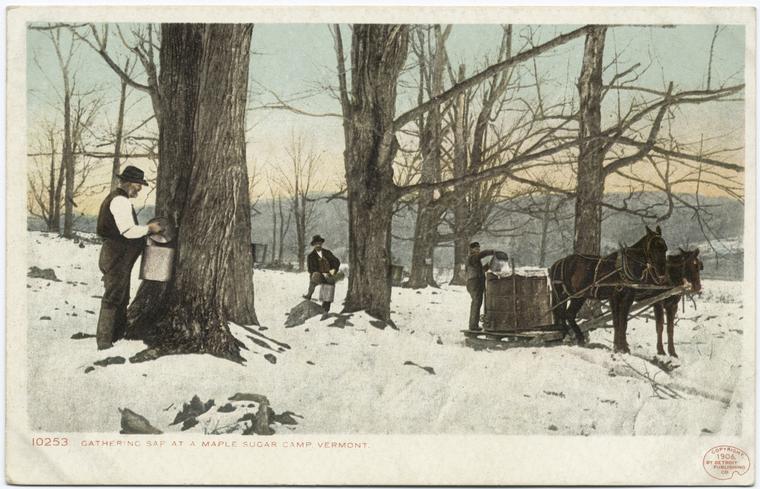

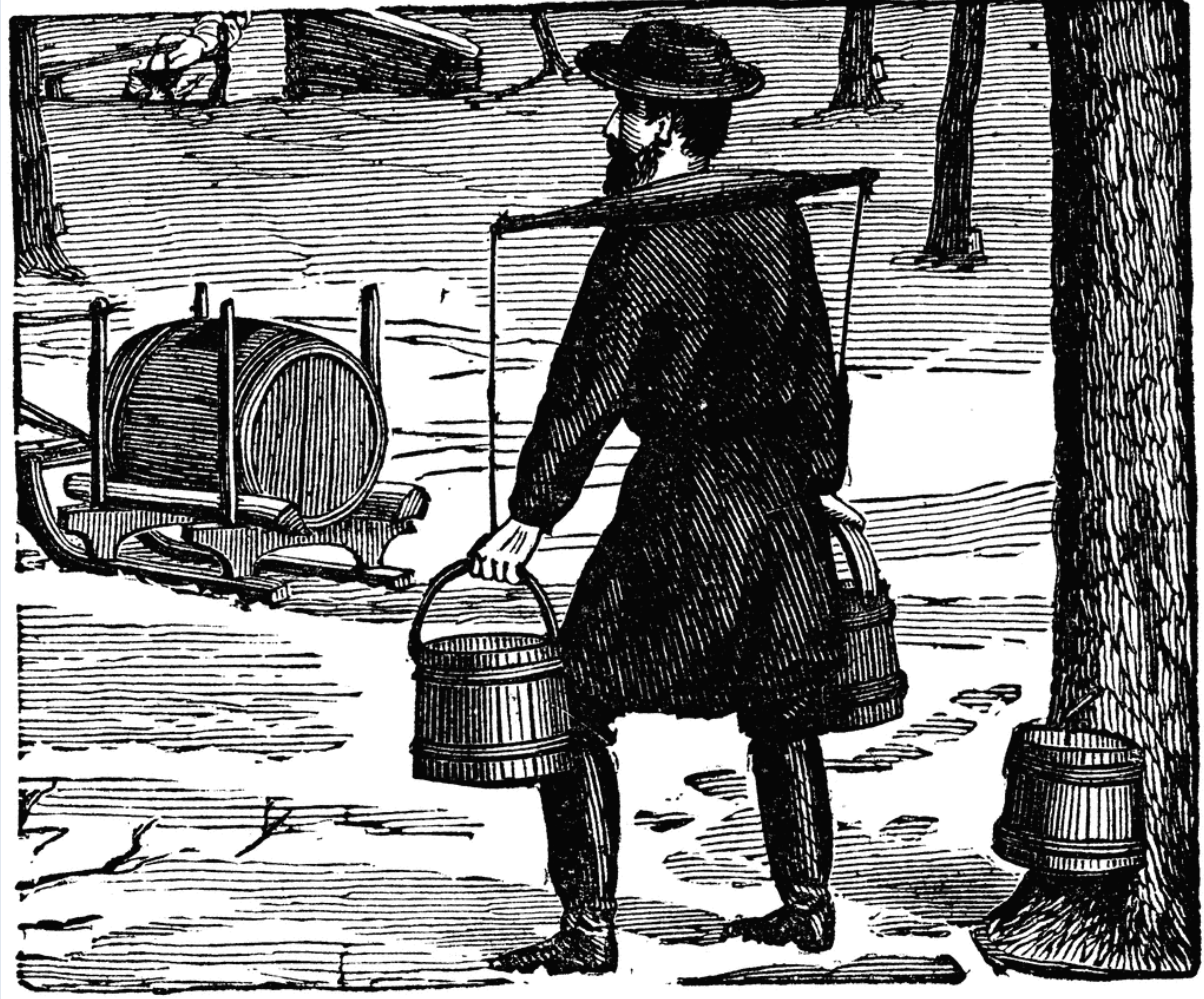

A “sugar camp,” by the way, was (and still is!) a place where people gather/camp to harvest maple sap for making maple syrup. The forested land where sugar maples grow is also called the “sugar bush.” Farmers maintain the forest floor to keep their young trees from any competing brush or saplings.

Today, we when see a whiskey described as having been “made with maple syrup”, we can pretty much assume that it’s been secondarily aged in used maple syrup barrels. While maple syrup is usually used as an additive flavoring these days, that wasn’t always the case. It was not uncommon for Pennsylvania’s early distillers to use maple sugar/syrup in their mashes and fermentations. It was added to the mash as an adjunct to aid attenuation during fermentation (conversion of sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide) and improve alcohol yields. And YES, maple syrup will ferment! It may seem a bit gratuitous to consider adding maple syrup to a mash today because of how expensive it has become, but it was more commonly available to distillers 150 years ago, especially during distillation season. Making maple syrup may also seem a very time-consuming endeavor, but no more so than any agricultural activity!

Pockets of maple tree groves around Pennsylvania supplied pioneer farmers with maple syrup in the fall and winter. Pennsylvania isn’t as well-known as other northeast states like New York and Vermont for its maple syrup, but PA ranks as the nation’s 5th largest producer today! Sugar maples tend to grow in higher elevations- in Pennsylvania the sugar bush camps were concentrated out west- in the Alleghenies. In fact, Somerset County, PA, which was famous for its fire heated pot still rye whiskeys in the mid to late 19th century, is STILL big in maple syrup production. Sugar maples actually grow in abundance here, though not as much as they once did. (Btw, It takes about 40 years for a sapling sugar maple to mature and reach 10-12 inches in diameter before it can produce enough sap and be tapped for making maple syrup, so Pennsylvania’s old forests held lots of potential.)

It was the Native Americans who taught pioneers how to tap the sugar maple trees for their sap. There are records going back to 1609 in the Americas explaining the methods used by the Native people. Pioneers in western Pennsylvania copied these methods and found a great deal of trading value in this sugar source. The Alleghenies provided farmers with rich, well drained limestone soils which made for excellent farming conditions. Farms are seasonal businesses, however, and the late winter and early spring thaws while the ground was still frozen presented an opportunity for sugar camps. Moonshiners would use the smoke from the sugar camps throughout the region to mask their own fires in the woods. I’ve read mentions of the use of maple sugar and syrup in making local products that neighbors sought out. I doubt many were using pure maple syrup to make spirits, but they were very likely using a bit to kick start fermentation.

Another use for all that sugar maple was in the use of charcoal. Men have understood the qualities of wood and have known how to make charcoal from hard woods for millennia. Native Americans maintained their sugar bush harvest by burning off underbrush in the forest with controlled fires. They understood that the ash from burned vegetation replenished the soil and nourishing the trees. They certainly understood wood charcoal. We all know about Tennessee’s Lincoln County Process, but that is a modern designation for a much older process. One of the basic origins of alcohol rectification is the use of charcoal filtering. Rectifiers used charcoal to filter whiskey of its impurities- namely fusel oils, which people understood to be poison. Many different types of filters have been used by American spirits rectifiers over the hundreds of years that they’ve crafting liquors (sand, granulated bone charcoal-bone black, cotton, shells, etc.). Sugar maple is a very hard wood and hard woods were used to make charcoal, plain and simple. It is said to impart “sweet” characteristics to the spirits that filter through it, though I’ve seen no proof of that. What I have seen is that sugar maple is the best and most plentiful hardwood for making charcoal. It was also very popular with wheelwrights and cabinet/furniture makers so sawmills would have had plenty of excess wood for use in making charcoal. It was a valuable wood in the lumber industry…but I digress.

Time for pancakes😊