It’s a funny thing to be so keenly aware of how little attention has been given to Pennsylvania rye whiskey history. The American whiskey industry has been so laser focused on selling the history of bourbon whiskey for so long that the history of American rye whiskey has taken a back seat as a second tier spirit. Rye whiskey is often described as a “prelude to bourbon”…which is, of course, ridiculous. Bourbon whiskey and rye whiskey coexisted in the marketplace before Prohibition, but as two very different styles of American whiskey. Each maintained their own fluctuating market share in the country by the late 1800s- rye maintain its superiority in the North and bourbon securing its favorability in the South. Bourbon whiskey did not really begin to show any dominance within the American marketplace until AFTER Prohibition! Even then, it did not truly rival the popularity of rye whiskey until after the 2nd World War. The 1940s and 50s ushered in an era of slow decline for the whiskey industry; Even as the amount of blended whiskey being produced and sold was ramping up, the quality and character of American whiskey was being dealt a blow. The last of Pennsylvania and Maryland’s rye whiskey producers (or at least those that were able to survive Prohibition) were closing their doors, and Kentucky’s bourbon producers were left to carry the torch for American whiskey.

Since Prohibition, American whiskey companies had been buying and trading whiskey brands, but all that trading in trademarks made for a very confusing consumer marketplace. A brand born in St. Louis might be manufactured in Kentucky, sold by a New York firm, and distributed out of a California warehouse. A label might show a famous Pennsylvania rye brand, but that whiskey may, in fact, have been manufactured in Illinois! All of this confusion seemed to have cultivated a desire within the industry to preserve American whiskey’s heritage. This is when we start to see Oscar Getz begin his American whiskey collection and museum. A “whiskey museum” , by the way, would have been laughable in a pre-Prohibition era! It would have been akin to forming an oil and gas or railroad museum- While those industries may seem distant and nostalgic to consumers today, they were active and ongoing at the turn of the 20th century! People don’t usually build museums to preserve the present;) Museums are built to commemorate the past, preserve history, and promote tourism. America’s whiskey distillers recognized the need to preserve the history of their industry as it began to slip away.

Today, we see many efforts by distilling companies to promote the history of American whiskey. Of course, it costs money to promote history, and museums don’t come cheap. But, where there’s a will, there’s a way! Bourbon companies have been at the forefront of preserving American whiskey history. Their stewardship of history, however, was always going to be biased. It was always going to be skewed toward the history of bourbon. We can witness this revisionist history continuing to happen today- even as recently as 2023 when Oscar Getz’s “Museum of Whiskey History” was changed to Oscar Getz’s “Museum of Bourbon History.” While Mr. Getz’s collection is based in Bardstown, Kentucky, the collection does NOT represent the history of bourbon. It represents the collective history of American whiskey- as Oscar Getz intended- a history that includes much more than just bourbon. Marketing has a way of getting carried away with itself…

In 2024, the Sam Komlenic Gallery was opened at the West Overton Village in Scottdale, Pennsylvania. Over 450 artifacts, including bottles and memorabilia, are on display in the gallery. It the largest publicly accessible collection dedicated entirely to Pennsylvania’s rich history of whiskey distilling. It is not a rye whiskey museum, though it does contain a great deal of Pennsylvania rye whiskey history! The need to preserve rye whiskey history is felt quite keenly in Pennsylvania. Most historians recognize that American whiskey history began in Pennsylvania, but until the Komlenic Gallery was opened last year, there was little effort to tell Pennsylvania’s story. Bourbon historians may be willing to admit that bourbon history has its roots in Pennsylvania, but they’d prefer to leave it at that! It seems Pennsylvania will need to find the will to carve its own legacy into stone and preserve its place in history.

There are several other galleries and museum exhibits dedicated to American whiskey history. There is the Whiskey Rebellion Education & Visitor Center and the Bradford House in Washington, Pa. The Fort Bedford Museum in Bedford, Pa also opened an exhibit in 2023 dedicated to the Whiskey Rebellion and to the rye whiskey distilleries that once flourished in the surrounding county. Museums don’t always go out of their way to advertise their whiskey history either! Sometimes whiskey history content is uncurated and just scattered within a museum’s collection. There is lots of whiskey paraphernalia in the Smithsonian, for example! One of my favorite museums with random whiskey history among its thousands of items on display is the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

The museum is packed from the floor to the rafters (5 stories above) with a hodgepodge collection of Pennsylvanian artifacts, most of which are from the 19th century. The collection includes everything from pottery to medicine to whaling boats! Among the thousands of objects are several items that relate to the liquor industry- like whiskey and apothecary bottles, barrels, milling equipment, and stills.

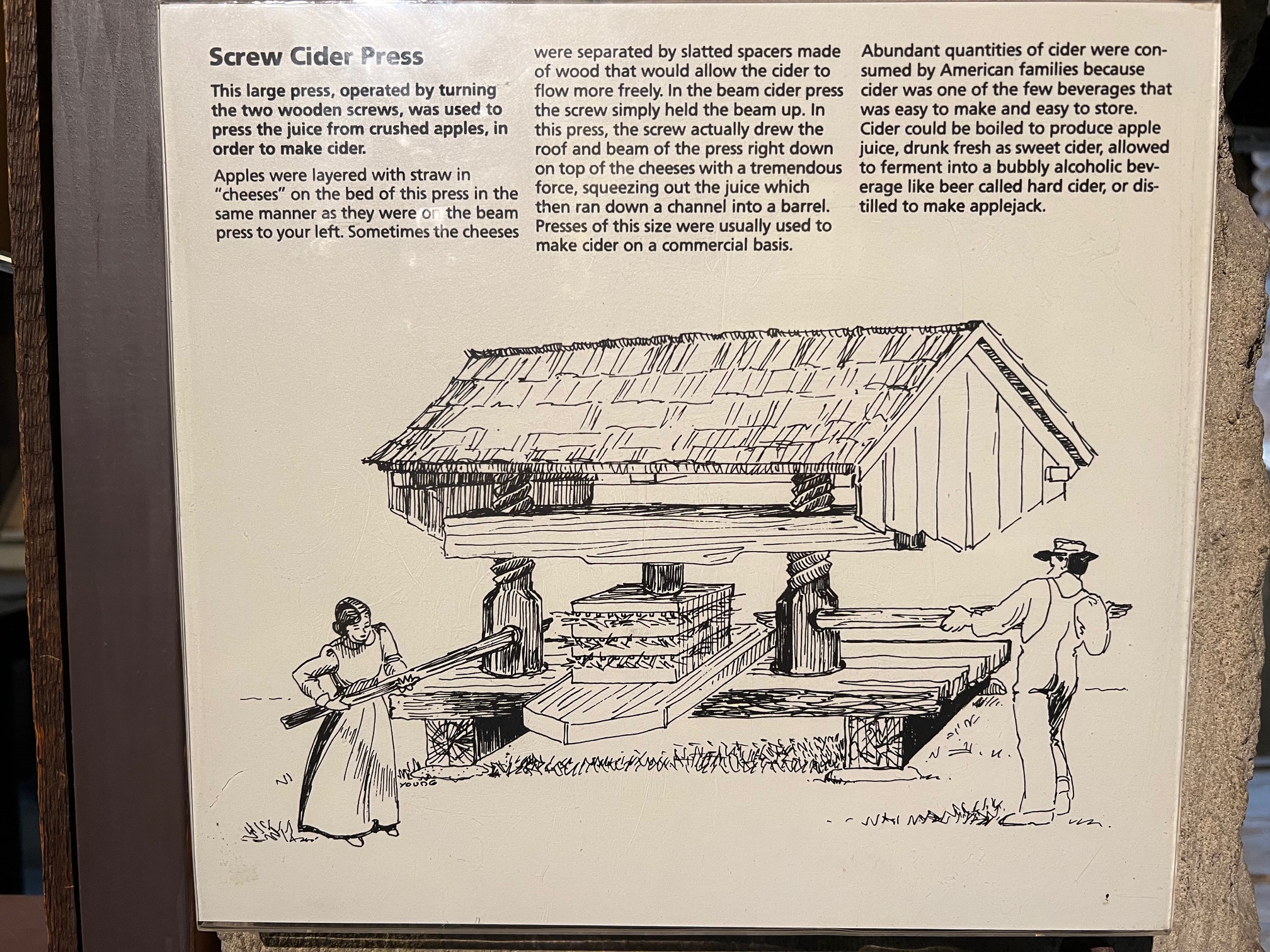

The following images are of presses and cider mills. While they are not directly connected to whiskey, they are definitely connected to apple brandy production. Almost every Eastern Pennsylvania rye whiskey distillery manufactured apple brandy each autumn season. Smaller production facilities may have used presses like the one you see here- This fruit press, manufactured in Springfield, Ohio, is accompanied by a description:

The following images are of presses and cider mills. While they are not directly connected to whiskey, they are definitely connected to apple brandy production. Almost every Eastern Pennsylvania rye whiskey distillery manufactured apple brandy each autumn season. Smaller production facilities may have used presses like the one you see here- This fruit press, manufactured in Springfield, Ohio, is accompanied by a description:

“Fruit presses-

Presses like these were used on many farms and homesteads in rural America to make apple cider and wine for home consumption. Although these presses vary widely in design and construction- some are simple and homemade and others are quite elaborate- they all work on the same principle as the much larger commercial presses.

“The press pictured “is an apple grinder and cider press combined. The apples were fed through the hopper on top into the grinder, which crushed them. The crushed apples were then moved underneath the screw and the juice was pressed out. It flowed through a slatted container and was channeled into a barrel placed on the ground. (…)

“Apples, grapes and other fruits were among the very first thing a farmer planted. Throughout the 19th century, nearly every farm and rural homestead had its own orchards and small vineyard.”

This second set of images is of a large mill press and an illustration of the press with information. To give you a idea of scale, those screws are about 12” in diameter.

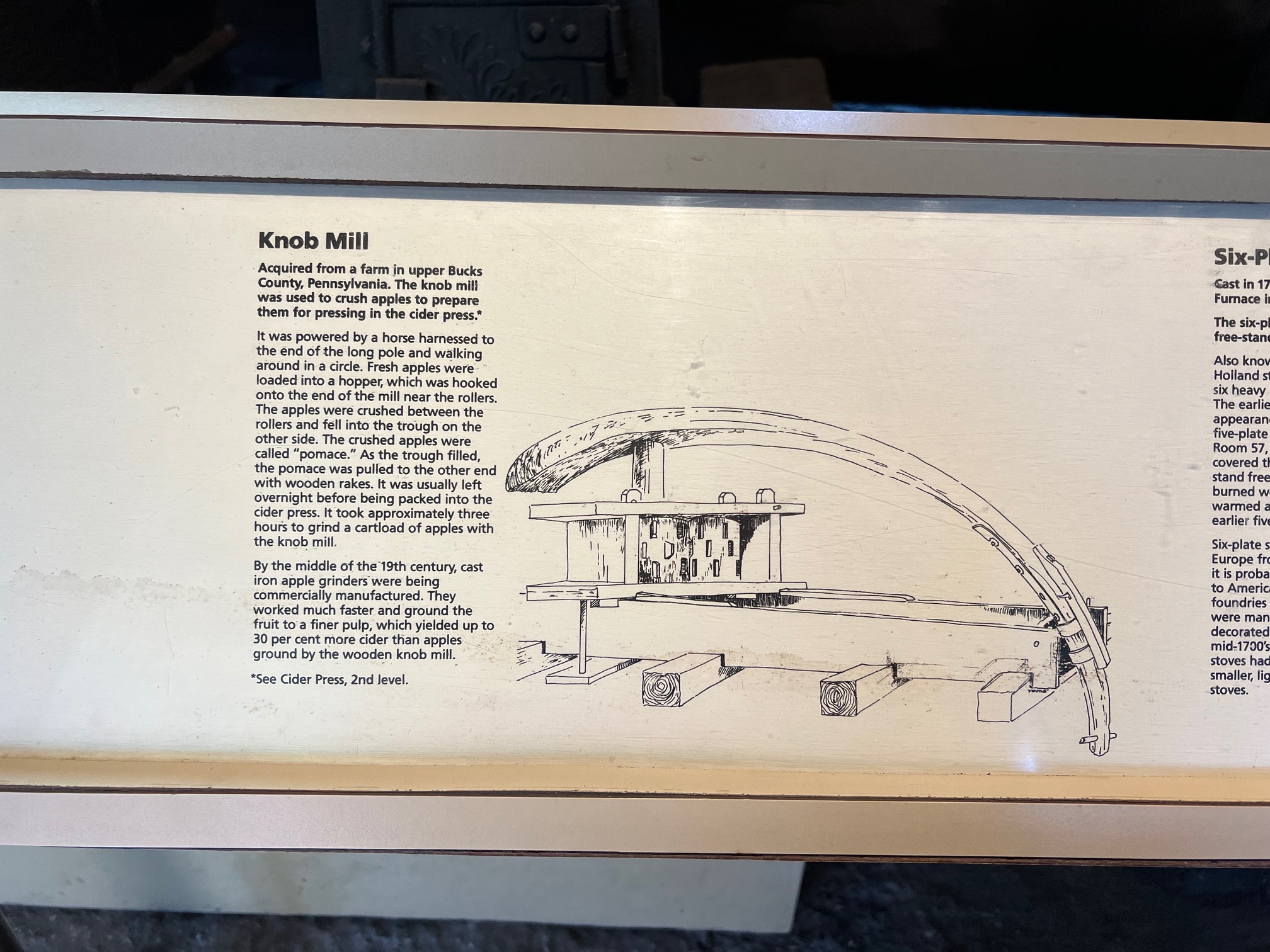

The third set is of a “knob mill”, made in Bucks County, Pennsylvania! Would be great to see that thing in action.

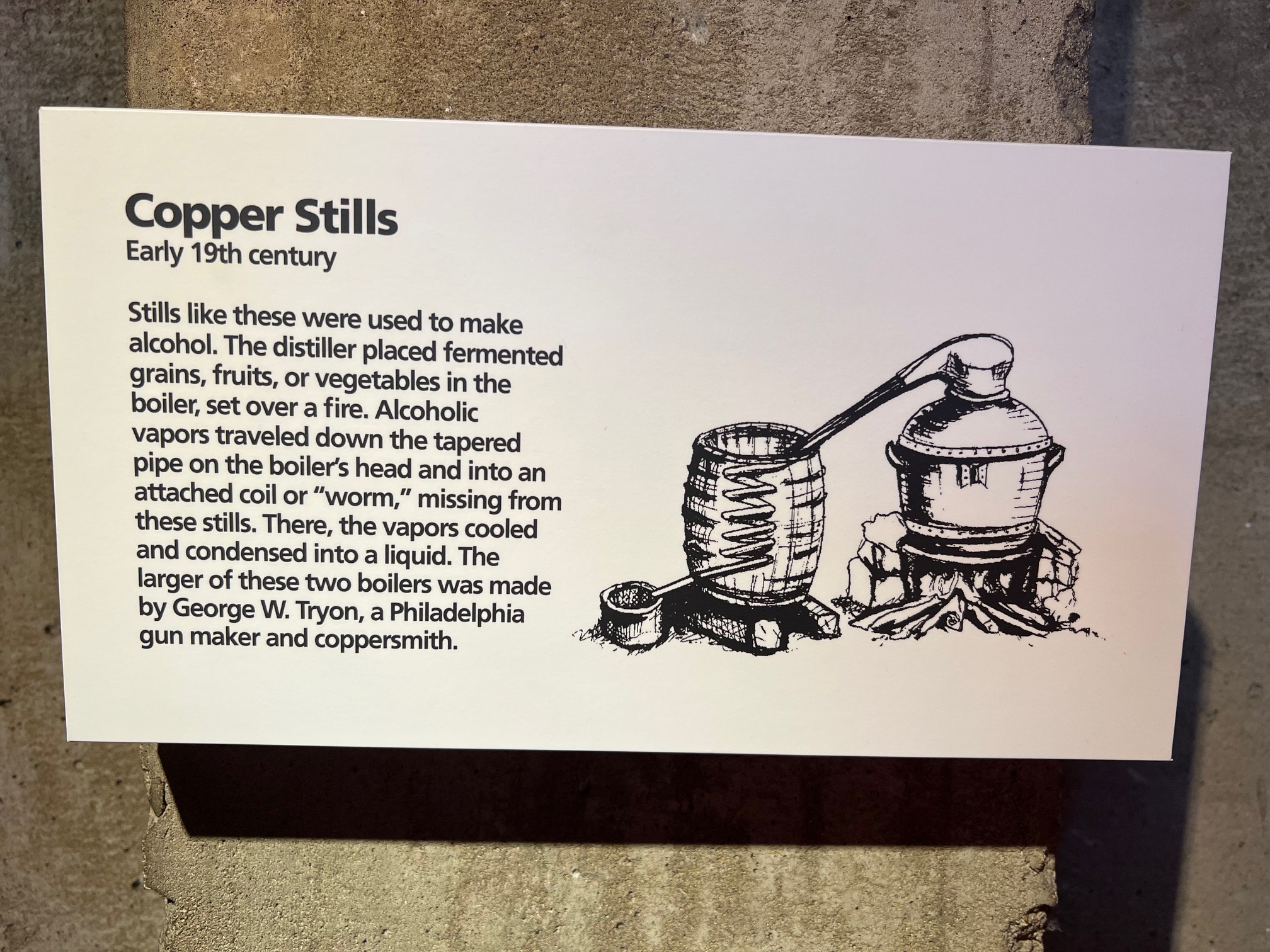

Perhaps the most obvious whiskey-related items at the Mercer Museum are the copper pot stills, made by George Tryon of Philadelphia . The stills’ description plate explains that the larger of the two stills was made by “George W. Tryon”, but I’m pretty sure the museum has named the wrong George Tryon! George W. Tryon was a famous gunsmith in Philadelphia, and while he owned several businesses, there was also a George T. Tryon who owned a tin and coppersmith shop at 2nd and Race Streets in Philadelphia. I found another reference placing a George Tryon at 2nd and Race. George W. Tryon’s gun shop (he was famous for his high-quality rifles) was on Vine Street, not Race. The two men were living in Philadelphia at the same time at different addresses. The sign should read George T. Tryon as the maker.

Philadelphia had many manufacturers of copper stills; The city became famous for their production of copper pot stills. Even in Kentucky, Philadelphia-made pot stills were sought after for their quality in craftsmanship. In fact, the early history of distilling in this country can be traced by simply “following the stills.” Larger copper stills that had been imported from Europe remained in the city where they were unloaded. While stills being manufactured in Philadelphia reached thousands of gallons in size, they didn’t go far from the city. Their size and weight limited how far a still could be moved from its place of manufacture. Before the establishment of the railroad, the sizes of pot stills tended to be smaller the further west you went because they had to reach their destination by wagon! You start to see larger stills making it to Western Pennsylvania and onto rivercraft by the early 1800s, but movement was always limited by the capacity limits on any mode of transportation. This is also why we see larger stills in the West made of wood instead of metal. Boilers did not need to be as large as stills, so as soon as steam technology in distilling was introduced in the late 1700s and early 1800s, boilers were used to create the steam needed to heat larger capacity wooden stills. Wooden stills remained in use right up until Prohibition in Pennsylvania. Several large-scale distilleries employed them.

In the end, whiskey history can be found just about anywhere in the United States. It is woven into our cultural tapestry. All we need are interested parties to help preserve that history. Museums dedicated to whiskey become tourist destinations. Pennsylvania’s got its work cut out for it when it comes to straightening out the history of American whiskey where rye is concerned, but any job worth doing is worth doing well. Here’s hoping that the interest that consumers have developed around rye will translate into more museums and educational opportunities in the future!