This has been an ongoing debate for a while now…even if the debate should have taken place in the 1930s. (Hindsight is 20/20, they say…) Disclaimer: The following information and opinions on this topic are offered from a third party perspective. My perspective has been shaped by 10+ years of independent research into the history of rye whiskey in Pennsylvania, as many years interacting and sharing information with Pennsylvania’s distillers and members of its grain supply chain, and from my own experience enthusiastically promoting Pennsylvania rye to anyone that will listen. My non-profit, the Delaware Valley Fields Foundation, has always prioritized rye (especially heritage varietals) through its SeedSpark Project.

The question posed is- “Should Pennsylvania rye whiskey have its own category in the American liquor industry?”

My personal belief is that it IS important to establish a category for Pennsylvania rye whiskey. There are several reasons why it is important:

1. A Pennsylvania rye whiskey category would unite its distillers under one banner. Those making rye whiskey in Pennsylvania should benefit from their state being the birthplace of American whiskey. (While the argument has been made that a category specific to rye would be exclusionary for other PA spirits, the interests of all of Pennsylvania’s distillers should be represented by Pennsylvania’s distillers’ guild.)

2. A rye whiskey category would provide incentive for Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey distillers to collaborate and support one another in the marketing of Pennsylvania rye whiskey- across the board. While each PA rye whiskey is unique, a category would inspire mutually beneficial goals for producers going forward. Above all else, a category creates a foundation for marketing! Pooling resources and promoting Pennsylvania rye whiskey together is in everyone’s interest.

3. Pennsylvania rye whiskey very literally has more historic claim to the title “America’s native spirit” than any other style of brown liquor in the U.S. (Sorry, rum producers, but Pennsylvania was never known for rum the way it was known for rye whiskey. Again, that is another conversation worth having with the guild.)

I believe that a category should, first and foremost, elevate the importance of Pennsylvania’s history in whiskey-making and the efforts being made by modern distillers to reclaim that legacy. In other words, it should be created with the goal of marketing the importance of Pennsylvania rye over other styles of rye whiskey made in the United States. Kentucky’s bourbon producers, in their way, continue to elevate the status of Pennsylvania rye whiskey’s history, which is something Pennsylvania should use to its advantage. A category can help to show the rest of the whiskey industry that Pennsylvania has a collective desire to retain and control its own history (which is much older than bourbon’s!), reclaim its place in the history books, and shape its own future. Pennsylvania rye whiskey distillers have a great deal to gain by working together toward a common goal.

Most discussions on creating a category for PA rye whiskey tend to skew toward specifics about mashbills and legal issues, but I think distillers should be careful about getting too specific. Categories SHOULD be specific, but the discussion should remain focused on how a PA rye whiskey category might benefit the consumer. It’s worth remembering that the purpose of a category isn’t just to preserve the dignity of Pennsylvania whiskey- It’s also to sell that rye whiskey to lots of people! Consumers have to take as much pride in the specifics described in the definition as the distillers that make it. Keeping it simple is key, especially when categories for rye whiskey already exist. The following are examples of the legally defined categories for rye whiskey in the U.S. (as of September 2025):

- TTB’s General Type Definition of Rye Whisky:

“Whisky produced at not exceeding 80% alcohol by volume (160 proof) from a fermented mash of not less than 51 percent rye and stored at not more than 62.5% alcohol by volume (125 proof) in charred new oak containers” - Maryland Rye Whiskey:

As of October 1, 2023, (approved by Governor Wes Moore on May 3, 2023) Maryland Rye or Maryland Rye Whiskey is officially recognized as Maryland’s state spirit by “State Bill 497”. - New York State’s Definition for “Empire Rye”:

(1) Must conform to the New York Farm Distiller (Class D) requirement that 75% of the mash bill be New York grain; in this instance that 75% MUST be New York State-grown rye grain, which may be raw, malted or a combination;

(2) The remaining 25% of the mash bill may be composed of any raw or malted grain, New York-grown or otherwise, or any combination thereof;

(3) Distilled to no more than 160 proof;

(4) Aged for a minimum of two years in charred, new oak barrels at not more than 115 proof at time of entry;

(5) Must be mashed, fermented, distilled, barreled and aged at a single New York State distillery;

(6) A blended whisky containing no less than 100% qualifying Empire Rye whiskies from multiple distilleries may be called Blended Empire Rye. - Indiana’s Legal Definition for Indiana Rye Whiskey:

(1) manufactured in Indiana;

(2) produced with a mash bill that is at least fifty-one percent (51%) rye;

(3) distilled to not more than one hundred sixty (160) proof or eighty percent (80%) alcohol by volume;

(4) aged in new, charred white oak barrels;

(5) placed in a barrel at not more than one hundred twenty-five (125) proof or sixty-two and one-half percent (62 1/2%) alcohol by volume;

(6) rested in a rack house for at least two (2) years in Indiana; and

(7) bottled at not less than eighty (80) proof or forty percent (40%) alcohol by volume.

While other states have established categories for their state’s whiskeys (Texas, Tennessee, Missouri), these official definitions are specifically designed for rye whiskeys. Notice how Maryland skipped the creation of a distinct category, choosing instead to establish rye whiskey as their state’s official spirit. This was probably wise considering how similar Maryland rye whiskey was to Pennsylvania rye whiskey. New York chose to invent and trademark the name “Empire Rye,” distancing themselves from competitors by creating their own identity. The Empire Rye category prioritizes local grain production, adding a “straight” whiskey designation (min. 2 years old), as well. Indiana built their category around provenance, also adding the “straight” designation. Each state’s category is significant in that they prioritize and elevate the significance of rye whiskey production within each state. Pennsylvania has more claim than any other state in the union to rye whiskey, so it’s high time PA pushes that historic advantage.

To place the discussion of a Pennsylvania rye whiskey category in context, I thought it would be important to explain a few things. First, I’ll explain how the standards of identity came to be established in the first place. Then, I’ll get into a little history on how Pennsylvania rye whiskey earned its prominent place within the whiskey industry. You can’t know where you’re going unless you know where you’ve been, right? At the end of the article (feel free to scroll ahead!), I’ll explain the 5 characteristics that differentiated Pennsylvania rye from other whiskeys. I am not providing this information to guide any decisions about what a modern Pennsylvania rye should look like. On the contrary, I do not believe that modern Pennsylvania ryes should be tethered to the past. I am including these details because they provide context and may help to inform or clarify details about what Pennsylvania rye USED to be. Bourbon history has had the unfortunate side effect of muddying the unique history of rye whiskey. Pennsylvania rye deserves to be recognized for its contributions, separate from that of bourbon.

The idea that a category should be established for a spirit is a relatively new concept for the American spirits industry. We may take for granted that the TTB has legal standards of identity for spirits, but that hasn’t always been the case. Today, there are categories for neutral spirits, vodka, gin, rock & rye, scotch, cordials and liqueurs, brandies, etc… and for whiskeys. Each of these categories have subcategories or “types”. Types of whiskeys include corn whiskey, straight whiskey, light whiskey, spirit whiskey, bourbon whiskey, rye whiskey, whiskey distilled from specific mashes…and the list goes on. This is all fairly common knowledge, but what it less commonly known is that these distinct categories did not exist at all until 1935, were not legally enforced until 1936, and have evolved to mean different things since then.

The standards of identity were created by FDR’s newly formed Federal Alcohol Administration (FAA) in cooperation with the Departments of Agriculture and Treasury. The FAA’s mandate was to collect data, to establish license and permit requirements, and define the regulations that ensure an open, fair marketplace for the alcohol industry and the American consumer. Rye whiskey held its own sub-category under the class of “whiskey,” while bourbon and corn whiskey were listed together under the same subcategory. It may seem odd to a modern whiskey drinker that rye once took precedence over bourbon, but it most certainly did. I do not say this to disparage bourbon, I say it to help explain that these categories were only ever made to establish fair trade and consumer protection from mislabeling or fraud. The industry could not have known what the future would hold for American whiskey. Today, the industry finds itself in unchartered territory.

Before Prohibition, standards of identity were controlled and maintained by the industry itself. A balance was tentatively achieved between government regulators and spirits manufacturers. Quality was maintained through a high degree of competition in the marketplace paired with strict regulations and oversight provided by the U.S. Department of Revenue. Producers built industry standards for the spirits they crafted the same way they built their brands and their reputations- slowly and deliberately over generations of uninterrupted distilling seasons. Pennsylvania earned its reputation for excellence by building upon the quality and craftsmanship of each consecutive generation. The standard for Pennsylvania rye whiskey’s identity rested comfortably on the consumer’s trust in “pure rye whiskey” and on the desire of rye whiskey producers to maintain their dominance within the trade. Prohibition, as we know, brought over 200 years of rye whiskey tradition crashing to a halt. The industry would be forced to start from scratch in 1933 because the thriving, competitive marketplace that maintained those industry standards before Prohibition had effectively been destroyed. There were over a hundred distilleries operating in Pennsylvania before Prohibition and about 35 operating immediately after Repeal, many of which were now in the hands of interests outside of the state. There are many reasons for Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey distilleries not surviving Prohibition as they should have, but none of those reasons involved rye whiskey falling out of favor with consumers. (You can be read more about those reasons HERE.) The point I’m making here is that Pennsylvania rye whiskey needed no introduction before Prohibition; It was was highly respected, highly sought after, and very valued within the liquor trade. While there may not have been a need to create standards of identity before Prohibition, these are very different times we’re living in. Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey makers no longer have 200+ years of consecutive years of distilling behind them…These days, there are less than 20. Making a connection to the past will require teamwork and a collective agreement on what rye whiskey means today. Of course, history can help guide the way!

“Pure rye whiskey” was collectively understood to mean that the whiskey in the barrel and in the bottle had been unadulterated through any rectification or dilution. Pennsylvania distillers only began to use the term “straight” in the 1890s after it gained favor with consumers and after outside interests began to invest heavily in Pennsylvania rye whiskey distilleries. “Straight,” like “pure rye”, was a term (not a legal definition) used by producers to describe whiskey “straight from the barrel”. The “straight whiskey interests” had a powerful lobby and were gaining momentum in the trade. Rye whiskey producers embraced the term “straight” when it suited them, but “pure rye” was universally understood to be rye whiskey’s synonym for “straight”.

While Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey distilleries were spread across the state and usually located in the countryside, their owners usually kept home offices in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. It was in these two cities that owners maintained the business of their vast trade networks. They also organized annual meetings in grand hotels and consolidated their lobbying power to maintain the integrity of rye whiskey for everyone’s benefit. Rye whiskey didn’t become a force to be reckoned with overnight. Rye whiskey men built generational wealth by slowly building upon their empires for over 100 uninterrupted years. At the time, they felt no need to protect their products from anyone larger than themselves. The rye whiskey makers were insular and kept out outsiders they considered “carpetbaggers.”

Even during those defining years for the American whiskey industry at the turn of the 20th century when the Whiskey Trust was reorganizing itself to become the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (1895) and creating the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Co. as a subsidiary (1899) from 90% of Kentucky’s bourbon distilleries, Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey distilleries were able to maintain their independence- rejecting all buyout offers and continuing to go on about their businesses. Rye whiskey maintained its status as the most valuable American whiskey on the market before, during, and even after Prohibition!

With all the research I have done into 150+ unique Pennsylvanian distilleries, I have come to the conclusion that Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey distilleries failed to survive Prohibition because they were not collectively protected by the corporate umbrella that sheltered Kentucky’s bourbon distilleries. When the Whiskey Trust (in its corporate form as the American Spirits Manufacturing Company) acquired most of Kentucky’s bourbon distilleries before the turn of the 20th century, those distilleries gained an advocate with all the political power of their new corporate guardians. While Kentucky bourbon distilleries were in the very capable hands of powerful, politically connected men during Prohibition, Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey barons had been hobbled by their unwillingness to sell out. There is a lot of history here, but suffice it to say that Pennsylvania’s distilleries limped away from Prohibition. The representatives of rye whiskey barons were not finished off by the advent of Prohibition, but they would fail to recover after losing the unified front they once shared. I don’t share this information to advocate selling out! If anything, the cautionary tale to tell is one that would advocate long term strategies for Pennsylvania distilleries. There is a great deal to learn from history, even when it’s what not to do. Prohibition was a unique and horrible blow to the spirits industry. We should all hope that no none is stupid enough to want to relive that awful history.

Now, we must return to the unchartered territory of the present. Today, there exist in Pennsylvania nearly as many individual distilleries as there had been before Prohibition. Believe it or not, there are about 140 active distilleries in PA (This account was written in 2022, and that number has dwindled in 2025 when this post was updated). The differences between these active distilleries are obvious to anyone willing to tour the state and visit these unique businesses. Boundless history, much older than that of any other American whiskey, has inspired so many entrepreneurial businessmen and women to begin making rye whiskey in the Keystone State again. Allowing Pennsylvania’s distillers to once again own their lost and forgotten history would be invaluable to Pennsylvania’s modern distilleries.

So, what differentiated Pennsylvania whiskey historically from other distilleries making rye whiskey in America? Rye whiskey was being manufactured in many other US states (Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Missouri, Kentucky, etc.), but Pennsylvania rye existed in a class of its own. This trade prestige was won slowly and over the course of generations. It would be entirely accurate to call Pennsylvania rye whiskey “America’s native spirit”. Consumers sought out pure rye whiskeys from Pennsylvania because they knew that the best rye whiskeys had always been made in Pennsylvania. Before advertising or label trademarks became commonplace in the late 1800s, the country’s taverns, hotels, and saloons were able to mark up prices on “old rye” because they knew that Pennsylvania’s “old rye” sold itself!

When the advertising of products became more commonplace in the mid-19th century, “Old Monongahela,” “Old Rye Whiskey” and “Pennsylvania Pure Rye Whiskey” had become trusted label designations for retail products. Consumer trust had been earned over many generations. Even today, collectors of antique whiskeys recognize the significance of Pennsylvania’s historic rye whiskey brands.

While most of Pennsylvania’s historically impactful whiskey brands would fade into memory after 1917, the brands that WERE able to survive Prohibition were only able to do so through corporate acquisition. Legacy brands like Bridgeport Pure Rye, Old Overholt, Large, Guckenheimer, Sam Thompson, Joseph S. Finch, and Dillinger maintained their name recognition under new ownership. During Prohibition, the handful of corporate entities controlling America’s whiskey stocks were able to maintain legitimacy through their ownership of household brands. Pennsylvania’s whiskey stocks were sold during Prohibition as “medicinal whiskeys”.

“Pure Rye Whiskey” and “Pennsylvania Rye Whiskey” held the public’s fascination long after the distilleries where they were manufactured were gutted and demolished and the original families that owned the brands passed away. Kentucky distilleries continued to source rye whiskey from Pennsylvania distilleries well into the 1970s and 80s- even when their own distilleries were capable of manufacturing rye whiskey. Which begs the question…”Why would a Kentucky bourbon want to name its entire product line after a defunct Pennsylvania rye distillery?”

Why would the largest producer of American whiskey in the country use a Pennsylvania brand as a core product and advertise its historic connection to Pennsylvania with so much effort and at so much cost? Even Kentucky’s finest distillers know that the best rye whiskey was always made in Pennsylvania. The American distilling industry remembers that truth at its core- even if consumers do not. There are no books written on the history of American whiskey production that do not give credit to Pennsylvania rye whiskey for its contributions- because historians all know where that credit is due.

While the whiskey industry may praise the importance of Pennsylvania rye whiskey from an historic perspective, the assertion that rye whiskey existed as a precursor to Kentucky bourbon persists. Meanwhile, the facts are clear that rye whiskey and bourbon whiskey existed separately and were in competition with one another. It is important that we address the differences between these two popular styles of American whiskeys.

What were the differences between rye and bourbon production? If we look at the processes involved, almost everything was different. For our purposes here, let us assume that the reader has come to understand how bourbon is made. let me begin by saying that most whiskey enthusiasts are aware of how bourbon is made each rye whiskey distillery was unique unto itself. Just as today, distilleries had to operate within a large field of competitors and having a unique product was important. Let’s look at the following stages of production and how they may relate to modern Pennsylvania rye whiskey: 1. Grain- farming and agriculture, malting, and milling; 2. Mashbill and cooking the mash; 3. Yeast and fermentation; 4. Still design and distillation; 5. Warehousing and barrel aging.

1. Grain

Farming and Agriculture

While Pennsylvania rye whiskey was building a reputation for excellence in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, all the rye grain used in the distilleries was grown locally- usually within the same county (or neighboring county). This was usually because distillers tended to be wealthy landowners and/or millers who owned the land from which the rye crops were harvested. Even as the scale of operations within the state developed, rye was still grown within the state (mainly in the southeast) even as more rye began to be imported from Ohio, Michigan and the Red River Valley to supplement demand.

While the amount of rye grown in Pennsylvania has been reduced to historically low amounts, modern distillers may find that sourcing rye grain locally is still possible. Production levels TODAY are comparable to Pennsylvania distilleries from the early 1800s. That may be due to smaller batch sizes or inconsistent production schedules, but the fact remains that most new distilleries use tens of thousands of pounds of grain per year and not the millions that were once consumed. Today, farmers could once again benefit from the restoration of these traditional and very lucrative business relationships- distillery and farmer, together, as partners, growing together. As the distiller needs more grain, the farmer can expand their acreage, and both can benefit from the transaction…even if it may require a little improvement in their communication. After all, it’s been a hundred years, and they’ve been out of touch. Each could use a detailed reintroduction to the other and a crash course into what each requires from the other!

2. Mashbill

Cooking the Mash

Pennsylvania rye whiskey mashbills varied widely, but rye grain was almost always the main ingredient. Large rye whiskey distilleries also produced malt whiskeys and wheat whiskeys, but the core product remained rye whiskey. Everyone knew that location was their most marketable asset. In fact, in the 1890s, outside interests began buying land in the Monongahela Valley just because the provenance of the whiskey had become so important in the marketplace. Protecting the legitimacy of your brand had become a necessity with such a crowded field of rye whiskeys on the market, and salesmen knew that their customers were wise to falsehoods and imitations. Production location was more important than the contents of the mashbill. While our modern American mindset does not put much thought into a whiskey’s provenance, the pre-pro mindset was very similar to the one that we associate more closely with Europe. Location was everything.

“Rye and malt” usually meant rye and rye malt until Pennsylvania’s brewers made barley malt more financially viable for distillers. Thomas Moore’s Old Possum Hollow rye whiskey was described by Thomas Moore, “the pioneer distiller” himself, in the late 1870s as being 50% rye and 50% malt. This was based on his tried-and-true recipe that he had been using since the 1840s which makes it much more likely that the “malt” in his recipe was rye malt. Barley was never a large crop grown in Pennsylvania, and the mashbills (whiskey recipes) would have reflected that- at least early on. The fact that Moore’s mashbill was 50/50 also lends credence to this theory because a higher percentage of rye malt would have provided plenty of enzymatic conversion power for the mash. Before Prohibition, the rye varieties that were being used had higher protein content and they would have had higher conversion rates anyway.

As railroads made imported grain more available and large distillers added their own malt house facilities in the late 1800s, costs came down and “rye and malt” began to mean rye and barley malt. We tend to think that barley malt was a given- that Pennsylvania rye whiskey or Monongahela Rye whiskey was mostly unmalted rye with a percentage of malted barley added to the rye for its conversion power- but Pennsylvania rye whiskey is much older than the advent of industrial malt houses or the availability of barley to Pennsylvania’s distillers. We must remember that while the expense of using barley malt might have been an option for a small brewery, it would not have been for a distiller. Not only can much more beer be produced from the same amount of malted barley, but much more volume could be sold for immediate profit. Whiskey requires more grain to produce less product and takes years to mature! The boom in growth of Pennsylvania’s brewing industry in the late 19th century made barley much more available and helped to make barley malt much more cost effective for distillers. Distillery owners built their own malting facilities on site, invested in breweries, and took advantage of the railroad’s adjusted shipping rates. These distinctions are important because it helps to explain how rye whiskey’s ingredients evolved over time. The mashbills may have changed, but the commitment to excellence and the willingness to spend money to make a higher quality product never wavered.

Once the grain arrived at the facility and was approved by quality control, it was cleaned and brought into the distillery, malted or unmalted, and fed into the mill. The size of the distillery determined how this was done, but generally, the distillery milled its own grain using roller mills because they were compact, consistent machines that didn’t require too much maintenance. Grain amounts were closely monitored by a government gauger from the moment the grain entered the facility. Measurements were taken before and after the grain entered the mashtun for cooking. Because rye whiskey was sweet mashed, water was added to the mashtun instead of backset. The mash was cooked in large, steam-heated cookers for several hours- depending on what grains were being cooked. If corn was part of the recipe, the time was longer and the initial temperature used was higher.

The differences between how bourbon mashes and rye whiskey mashes were cooked and fermented was quite different. This was known within the industry and is why distillers were so specialized in their fields of expertise. In fact, with a highly competitive whiskey market, the rye distillers were forced to form a lobbying group in 1869 to protect their unique processes from being held to the same standards of other whiskey producers. The Internal Revenue Department attempted to standardize fill levels and fermentation times for all distillers, and rye whiskey men formed a commission to explain why their methods were different and needed room to remain so. Temperatures for cooking are lower for rye, fill levels were lower to prevent overflow during fermentation, and fermentation times differed depending on the grains and malt used in the mashbills. Each distillery used different methods to create their unique products and needed to be given the allowances to do so. They were successful, by the way- thankfully, the standards sought were not implemented and the rye manufacturers were able to continue their unique process.

Today, Pennsylvania rye whiskey distillers are still coming into their own. They are still discovering what separates their process from the rest. The nature of rye grain forces a distiller to reevaluate their decisions on everything- from milling, to the percentage of malt used, to what type of equipment best suits their needs. I have yet to meet a rye whiskey distiller in Pennsylvania that has not expressed to me how they’ve had to reevaluate their production process since they began in the business. (I’ve met and talked with at least 50 of PA’s current distillers.) The idea that a specific mashbill should be placed upon what it means to be a Pennsylvania rye whiskey should not be more than what the government has already put in place. That is, at least 51% of the recipe must be rye- without any distinct variety necessary.

3. Yeast and Fermentation

Pennsylvania distillers, like most “pure rye” or “straight whiskey” distilleries before Prohibition, had great pride in their yeast strains. Almost every distillery had a separate “yeast room” where the yeast was propagated and kept in isolation. Distillers had expertise in culturing and caring for yeast. The practice of maintaining a yeast strain was as old as the practice of whiskey distillation, so its mastery was highly respected within the trade. As distilleries grew in size, special management job positions were created specifically for the distillery’s chemist whose job it was to preserve and maintain the yeast. Pennsylvania rye whiskey had always been made with a sweet mash- with very few exceptions. This meant that each mash was prepared identically with fresh grist and fresh yeast. The yeast was pitched into cooked mash as it was pumped from the mashtun into large, wooden vats for fermentation.

4. The Still and Distillation

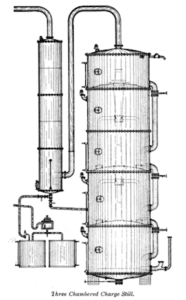

The beer still was usually a chambered still, though pot stills were still very common, even up until Prohibition. Somerset County, for instance, remained famous for its fire-heated, double copper pot still distillations of pure rye whiskey into the 20th century. Here is a description of the chambered stills-

“Two, three or more chamber charge-stills, with or without charging chamber in one apparatus, in which the single compartments are placed one over the other, and the heat from the lower serves to enrich the one above. Steam is used for heating. All these apparatus, when heated by direct firing, are made either of copper or iron; when heated with steam are made generally of copper, but ofttimes of wood, such as heavy cypress or white oak. These are more suitable for intermittent working, and are used mostly in distilleries which distil rye whisky, etc.”

(excerpt written by Richard Ferris, C.E., Sc.D. for The Encyclopedia Americana, 1923.)

Most distilleries, especially the large distilleries, had a set up like this: A large copper or wooden chambered still served as a beer still where fresh mash could be pumped for initial distillation. A smaller copper doubler acted as a spirit or refining still. The alcohol vapor was condensed through a long, copper worm which wound through a large flake stand outside of the still house. When the worm was not present, a condenser was used. The finished distillate ran through a separator (separates high wines and low wines) and, finally, into a cistern. While this was the normal template for some of the most famous rye whiskeys made in Pennsylvania, these methods had not been revealed to the public (or, more importantly, to the distillers themselves) until fairly recently. Most of the modern distilleries in Pennsylvania have designed their distilleries after an older, pot still style of Pennsylvania rye whiskey. This is no less accurate, historically. The thing that was completely absent from Pennsylvania rye whiskey distilleries until after Prohibition was the column still. There was only one column still present among the 150+ distilleries that I have researched, and that example did not show up until after 1905. It was brought in by out-of-state interests. This is not to say that column stills did not become the norm after Prohibition. But even when they were embraced for their increased efficiency, the column still simply replaced the chamber still as the beer still, and it was operated as such. The doubler and the condenser remained an important part of the process.

5. Warehousing and Barrel Aging

The majority of Pennsylvania’s rye distilleries used steam heat in their bonded, masonry warehouses. I am not aware of any large-scale rye whiskey distilleries that did NOT use steam heat in their warehouses. Most warehouses stacked their barrels three high with wooden shims between the barrels, but some, like Joseph Finch in Pittsburgh, matured their barrels on patent racks. Warehouses were kept hot- ALL YEAR ROUND. Steam heat would maintain constant temperatures of anywhere from 80 to 95 degrees. This style of heating warehouses was not unique to Pennsylvania, but it was insisted upon in the creation of pure rye whiskeys in the late 19th century. Consistently hot temperatures matured rye whiskey differently in the barrel- all that heat maintaining active maturation of the rye whiskey contained within, at least on a molecular level, throughout every season.

Pennsylvania distillers did not embrace the use of 53 gallon barrels until after Prohibition. While no standard size exists for barrels in the industry (even today), before Prohibition, Pennsylvania leaned toward smaller, tierce-sized barrels (42 gallon). This was largely due to Pennsylvania playing a major role in the oil boom during the mid-1800s. The standard size of an oil barrel was the tierce, so the whiskey industry embraced the use of that size barrel in their warehouses, too. Medicinal whiskey pints matured during the Prohibition years would not have been in barrels larger then 48 gallons. Curious to think how differently rye whiskey would have matured under these circumstances.

Conclusion?

While most Americans may not realize it, Pennsylvania was home to some of the most famous whiskeys ever made in this country. It’s not even ancient history! Even today, some of the most recognized brands of rye whiskey were born in the Keystone State. Modern brands like Rittenhouse Rye, Old Overholt Rye, Highspire Rye, Kinsey Rye, Meadville Rye, and Michters Rye earned their fame in Pennsylvania. Right up until Prohibition, Pennsylvania’s thriving rye whiskey empire was content to rest on its laurels- even as it avoided the onslaught of proposed buyouts and corporate takeovers. And they were doing so well at maintaining their independence that when Prohibition did hit the industry with a sledgehammer, their independence became a flaw- leaving them without the unified shield necessary to sustain the impact. After 100 years, however, a renaissance is underway. The rules are different, but the game is at least allowing Pennsylvania distillers to play again.

Pre-Prohibition brands like Guckenheimer Pure Rye, Gibson’s Pure Rye, Dougherty’s Pure Rye, Bailey’s Pure Rye, and Thomas Moore’s Possum Hollow rye were made famous even after Prohibition. Sam Thompson’s Rye and Old Vandegrift Rye may not be around anymore, but many of us may remember them from our parent’s liquor cabinets. One of the weaknesses in the modern argument for Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey as a category is that we lack the general knowledge to support it. We often see Old Overholt praised as a guide for what Pennsylvania rye whiskey once was- as the quintessential pre-Prohibition rye whiskey. And yes, Old Overholt was a very well-known brand, but it was only made more so by National Distillers, the largest owner of whiskey stocks after Prohibition. The Overholts didn’t start their distillery at West Overton until 1810 and the brand “Old Overholt” didn’t exist until 1888 when Charles Mauck introduced it using whiskey distilled at the company’s modern Broad Ford plant. It does not belittle the impact that the Overholt brand has had on Pennsylvania rye whiskey’s history to say that it was not the central figure of Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey’s story. Old Overholt was only one example of what Pennsylvania rye whiskey has been. It was a survivor, for sure, but it was only one among hundreds of unique brands. “Old Monongahela” rye whiskey was a regionally recognized style, but so was “Susquehanna rye whiskey,” an older traditional style of rye whiskey from the eastern part of the state.

The unifying characteristic of Pennsylvania rye whiskeys was its provenance. It is what makes Speyside whiskey or Islay whisky unique among other scotches. It is what makes Irish whiskey unique as a category. There are specific identifying characteristics that these whiskeys often possess (peated, unpeated, malted or unmalted grain, etc.) but their only universal characteristic is their provenance. There are always exceptions to any rule, as there should be. Pennsylvania’s Moore & Sinnott Distillery (aka John Gibson & Sons Distillery) toasted their unmalted grain AND their malted rye before it was mashed in. Does using toasted rye grain make them unique? Yes! Does it make their rye whiskey any less Monongahela rye whiskey? Absolutely not. If history can serve as a guide, we should allow modern distillers the same freedom their predecessors were given. If they want to add wheat or corn or specialty grains to their mash, it should not be excluded from being considered “Pennsylvania rye whiskey.”

I believe that having 250 years of distilling tradition and a legacy of excellence to draw from should qualify Pennsylvania rye whiskey with a category distinction today. However, before we go making decisions on what qualifies a rye whiskey as being a “Pennsylvania rye whiskey,” perhaps we should all look a bit closer at what Pennsylvania rye used to be. Not only should more credit be given to what it once was, but also to what it has become and to what it still has in store for future generations. A new category of rye whiskey should certainly be granted to Pennsylvania. Let’s just make sure it doesn’t exclude variations within the category. History shows us that Pennsylvania rye whiskey had many variations, but its most enviable quality throughout the industry was simply that it was exclusively made here. In Pennsylvania. After all, the only historically defining characteristic of ALL Pennsylvania rye whiskey was rye grain…and provenance.

More…

For those curious, the first time “rye whiskey” (or any whiskey) was defined by the US government was in 1935. These are the definitions of whiskey as defined by the FAA. Note that rye was defined before other variations. There was no distinct classification for Pennsylvania rye whiskey, but rye whiskey is always given priority.

Class 2: Whiskey

- Whiskey is an alcoholic distillate from a fermented mash of grain distilled at less than 190 proof in such manner that the distillate possesses the taste, aroma, and characteristics generally attributed to whiskey, and withdrawn from the cistern room at not more than 110 and not less than 80 proof, whether or not such proof is further reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80 proof and also includes mixtures of the foregoing distillates for which no specific standards of identity are described herein. Rye whiskey, bourbon whiskey, wheat whiskey, corn whiskey, malt whiskey, or rye malt whiskey is whiskey which has been distilled to not exceeding 160 proof from a fermented mash of not less than 51% rye grain, corn grain, wheat grain, malted barley grain or malted rye grain, respectively, and also includes mixtures of such whiskeys where the mixture consists exclusively of whiskeys of the same type.

- Straight whiskey is an alcoholic distillate from a fermented mash of grain distilled from a fermented mash of grain distilled at not exceeding 160 proof and withdrawn from the cistern room at not more than 110 and not less than 80 proof, whether or not such proof is further reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80 proof, and is-

- Aged for not less than 12 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1936, and before July 1, 1937; or

- Aged for not less than 18 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1937, and before July 1, 1938; or

- Aged for not less than 24 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1938.

The term “straight whiskey” also includes mixtures of straight whiskey, which, by reason of being homogeneous, are not subject to the rectification tax under the Internal Revenue Laws

- Straight rye whiskey is straight whiskey distilled from a fermented mash of grain of which not less than 51 % is rye grain.

- Straight bourbon whiskey and straight corn whiskey is straight whiskey distilled from a fermented mash of grain of which not less than 51 % is corn grain.

- Straight wheat whiskey is straight whiskey distilled from a fermented mash of grain of which not less than 51 % is wheat grain.

- Straight malt whiskey and straight rye malt whiskey are straight whiskey distilled from a fermented mash of grain of which not less than 51 % is malted barley or malted rye, respectively.

- Blended whiskey (whiskey-a blend) is a mixture which contains at least 20% by volume of 100 proof straight whiskey and, separately or in combination, whiskey or neutral spirits, if such a mixture at the time of bottling is not less than 80 proof.

- Blended rye whiskey (rye whiskey- a blend), Blended bourbon whiskey (bourbon whiskey- a blend), Blended corn whiskey (corn whiskey- a blend), Blended wheat whiskey (wheat whiskey- a blend), Blended malt whiskey (malt whiskey- a blend) or Blended rye malt whiskey (rye malt whiskey- a blend) is blended whiskey which contains not less than 51% by volume of straight rye whiskey, straight bourbon whiskey, straight corn whiskey, straight wheat whiskey, straight malt whiskey, or straight rye malt whiskey, respectively.

- A blend of straight whiskeys (blended straight whiskeys), a blend of straight rye whiskeys (blended straight rye whiskeys), A blend of straight bourbon whiskey (blended straight bourbon whiskeys), A blend of straight corn whiskeys (blended straight corn whiskeys), A blend of straight wheat whiskeys (blended straight wheat whiskeys), A blend of straight malt whiskeys (blended straight malt whiskeys) or A blend of straight rye malt whiskeys (rye malt whiskey- a blend) are mixtures of only straight whiskeys, straight rye whiskeys, straight bourbon whiskeys, straight corn whiskeys, straight wheat whiskeys, straight malt whiskeys, or straight rye malt whiskeys, respectively.

- Spirit whiskey is a mixture (1) of neutral spirits and not less than 5% by volume of whiskey, or (2) of neutral spirits and less than 20% by volume of straight whiskey, but not less than 5% by volume of straight whiskey, or of straight whiskey and whiskey, if the resulting product at the time of bottling be not less than 80 proof.

- Scotch whiskey is a distinctive product of Scotland, manufactured either in the Irish Free State or in Northern Ireland, in compliance with the laws of those respective territories regulating the the manufacture of Irish whiskey for consumption in such territories, and containing no distilled spirits less than three years old: Provided, That if in fact such product as so manufactured is a mixture of distilled spirits, such mixture is Blended Scotch whiskey (Scotch whiskey- a blend). Scotch whiskey shall not be designated as straight.

- Irish whiskey is a distinctive product of Ireland, manufactured in Scotland in compliance with the laws of Great Britain regulating the the manufacture of Scotch whiskeyfor consumption in Great Britain, and containing no distilled spirits less than three years old: Provided, That if in fact such product as so manufactured is a mixture of distilled spirits, such mixture is Blended Irish whiskey (Irish whiskey- a blend). Irish whiskey shall not be designated as straight.

- Canadian whiskey is a distinctive product of Canada, manufactured either in Canada, in compliance with the laws of the Dominion of Canada regulating the the manufacture of whiskey for consumption in Canada, and containing no distilled spirits less than two years old: Provided, That if in fact such product as so manufactured is a mixture of distilled spirits, such mixture is Blended Canadian whiskey (Canadian whiskey- a blend). Scotch whiskey shall not be designated as straight.

- Blended Scotch type whiskey (Scotch type whiskey- a blend) is a mixture made outside Great Britain and composed of-

(1) Not less than 20% by volume of 100 proof malt whiskey or whiskeys distilled in pot stills at not more than 160 proof, from a fermented mash of malted barley dried over peat fire, whether or not such proof is subsequently reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80 proof, and(2) Not more than 80% by volume of whiskey distilled at more than 180 proof and less than 190 proof, whether or not such proof is subsequently reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80 proof.

In Lieu of including the word “Type”, the designation may include the word “American” at the beginning thereof, if produced in the United States; or corresponding wording if produced in any other country outside Great Britain.

- Blended Irish type whiskey (Irish type whiskey- a blend) is a mixture made outside Great Britain or the Irish Free State and composed of-

(1) A mixture of distilled spirits distilled in pot stills at not more than 171 proof, from a fermented mash of small cereal grains, of which not less than 50% is dried malted barley and unmalted barley, wheat, oats, or rye grains, whether or not such proof is subsequently reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80 proof, or(2) A mixture consisting of not less than 20% by volume of 100 proof malt whiskey or whiskeys distilled in pot stills at approximately 171 proof, from a fermented mash of dried malted barley, whether or not such proof is subsequently reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80 proof.

In Lieu of including the word “Type”, the designation may include the word “American” at the beginning thereof, if produced in the United States; or corresponding wording if produced in any other country outside Great Britain.(3) Not more than 80% by volume of whiskey distilled at more than 180 proof and less than 190 proof, whether or not such proof is subsequently reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80 proof.

In Lieu of including the word “Type”, the designation may include the word “American” at the beginning thereof, if produced in the United States; or corresponding wording if produced in any other country outside Great Britain or the Irish Free State.