There is no doubt that Prohibition altered the American liquor industry in innumerable ways. The 18th amendment may have gone into effect in 1920, but the passage of the National Prohibition Act was made possible over the course of decades. State laws slowly chipped away at public opinion, making National Prohibition possible, if not inevitable. The country’s distillery owners had been battling temperance forces since the early 1800s, but their efforts were focused locally, often missing the bigger picture of what was taking place nationally. It took three quarters of a century to turn a handful of fiery preachers and zealots into a nation-wide movement with an organized political agenda. The prelude to Prohibition, which was well under way by the early 20th century, began in local courtrooms and eventually found its way to Congress.

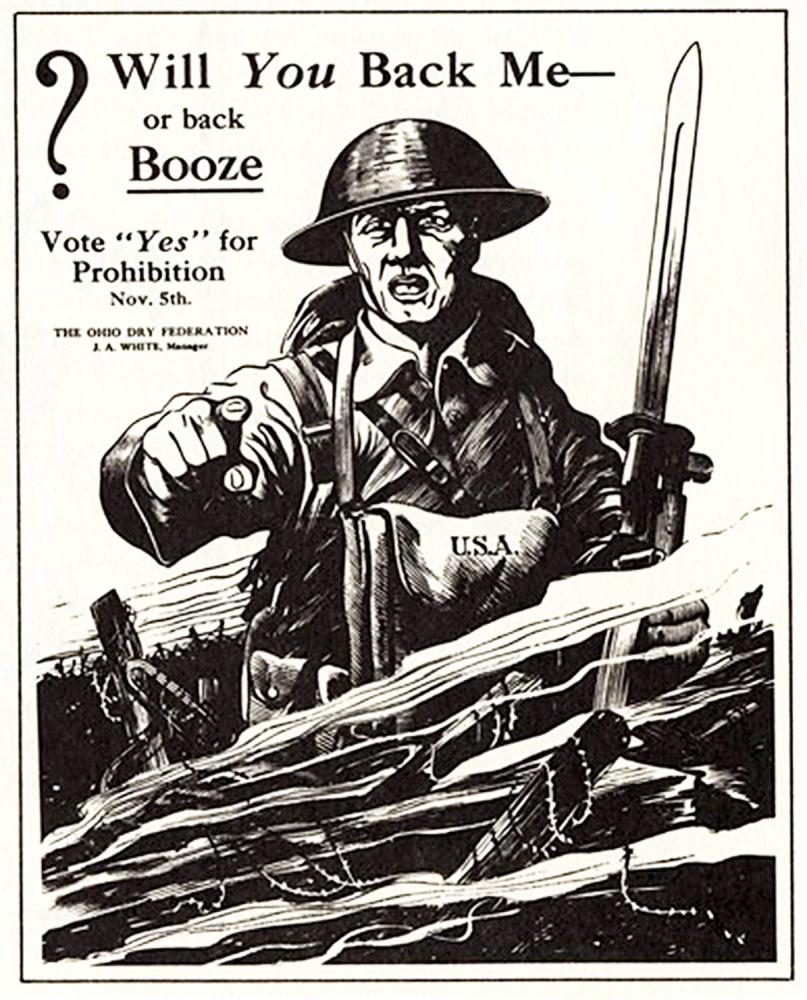

Distilled spirits were used as a moral wedge issue in politics.* The early 20th century saw a nation divided between the “wets” and the “drys” even if America’s citizens were more interested in being temperate in their liquor consumption than they were in complete abstinence or Prohibition. Small wins for the temperance groups were taking place at the local level where sympathetic court officials and politicians were elected to office. These officers could deny licenses to make or sell alcohol and sway public opinion to create dry towns and counties. Newspapers chose their sides and published editorials to promote their cause. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, founded in 1874 in Cleveland, joined by the Anti-Saloon League which became a national organization in 1895, brought their lobbying power to Washington. The temperance movement’s small political wins eventually won enough support within the US government to inspire big moves toward real national Prohibition legislation in 1917.

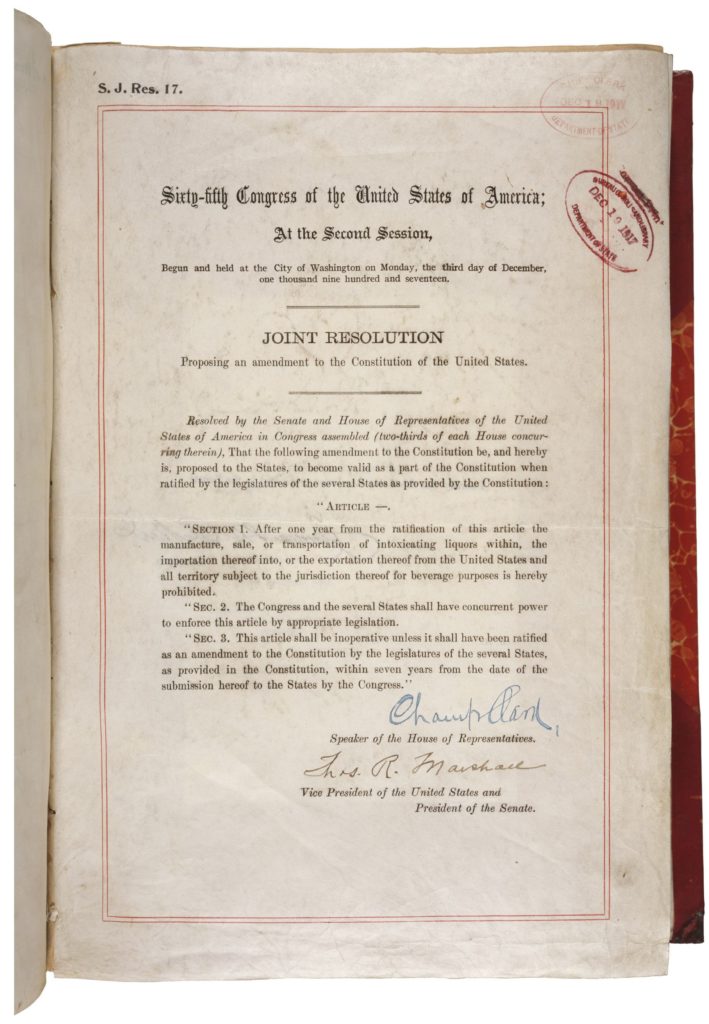

Two Congressional hammers fell on American liquor producers in August of 1917. The first blow came on August 1, 1917 when the U.S. Senate passed a joint resolution which proposed language for a constitutional amendment prohibiting the sale, manufacture, and distribution (but not consumption) of alcoholic beverages in the United States. While this resolution was just the first stage in the process of passing a new amendment to the Constitution, its approval was potentially disastrous. Congress revised the resolution on December 17, calling for a time limit of 7 years to be placed on ratification, and passed it the following day. Many distillers didn’t believe Congress would risk losing the fortune in excise taxes that were collected from distilleries, but they were now forced to face this potential danger. The burden of ratifying the U.S. Constitution’s 18th amendment would now fall to the states. If 36 of the 48 states ratified the amendment before the 7-year deadline, the 18th Amendment would become law. Prohibitionists were not happy with the time limit, but they were confident that they could achieve ratification in just a few years.

The second blow came just 9 days later. On August 10th, Congress passed the controversial Lever Food and Fuel Control Act. Its official name, “An Act to Provide Further for the National Security and Defense by Encouraging the Production, Conserving the Supply, and Controlling the Distribution of Food Products and Fuel,” explained its purpose. Dissenters of the law argued that the president should not have the power to limit or prohibit the use of agricultural products in the production of alcoholic beverages, which, in effect, would establish a form of national prohibition in advance of the 18th amendment. The wartime sentiment, however, overrode any concerns about the alcohol industry. Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey producers had faced production suspensions before, and many did not believe that ratification of the 18th amendment could be done in seven years. So, against all odds, Pennsylvania’s distillers continued to apply for licenses hoping that things would return to normal once the restrictions were lifted at the end of the war. Curiously, the Food and Fuel Control Act only banned the use of grain by distilleries, not the grain used by brewers or the grapes used by wineries.

The Prohibitionists got to work. One by one, the states began to ratify the 18th amendment.

- Mississippi: January 7, 1918

- Virginia: January 11, 1918

- Kentucky: January 14, 1918 (Straight Bourbon Producers)

It may come as a surprise to some that the state most recognized for American whiskey (bourbon) production in modern times was the third state to ratify the 18th amendment. Kentuckians, perhaps, would not find this as surprising as others, however. They know that 11 of the 120 counties in their state remain dry to this day (As of February 2020). 53 are wet, but the remaining 56 are either “moist” or dry with special circumstances. (The term “moist” is typically used for any county that allows alcohol to be sold in certain situations but has limitations on alcohol sales that a normal “wet” county would not have.) Decades before Kentucky cast its vote to ratify the Prohibition amendment, opinions about alcohol production and its use were shifting in the Bluegrass State. The vice-president of the National Temperance Society and native of Bourbon County, Kentucky, George W. Bain, was quoted by the Bucks County Gazette in 1908 saying, “When people say it is impossible to quit drinking, I tell them we are doing it down South. I can remember the time, twenty years back, when the sky of the South was black with the smoke of distilleries, and there was a saloon on every corner in every town, and at that time my life was threatened when I was delivering temperance lectures; but now I can speak anywhere in Kentucky, and in five years there will not be a legalized saloon in all the Southland. Forty years ago, you of the North took the shackles of chattel slavery from the South; we will now return the compliment of taking the shackles of rum slavery off you.”

- North Dakota: January 25, 1918

- South Carolina: January 29, 1918

- Maryland: February 13, 1918

- Montana: February 19, 1918

- Texas: March 4, 1918

- Delaware: March 18, 1918

- South Dakota: March 20, 1918

- Massachusetts: April 2, 1918

- Arizona: May 24, 1918

- Georgia: June 26, 1918

- Louisiana: August 3, 1918

- Florida: November 27, 1918

- Michigan: January 2, 1919

- Ohio: January 7, 1919 (Origins of the Whiskey Trust)

- Oklahoma: January 7, 1919

- Idaho: January 8, 1919

- Maine: January 8, 1919

- West Virginia: January 9, 1919

- California: January 13, 1919

- Tennessee: January 13, 1919

- Washington: January 13, 1919

- Arkansas: January 14, 1919

- Illinois: January 14, 1919

- Indiana: January 14, 1919

- Kansas: January 14, 1919

- Alabama: January 15, 1919

- Colorado: January 15, 1919

- Iowa: January 15, 1919

- New Hampshire: January 15, 1919

- Oregon: January 15, 1919

- North Carolina: January 16, 1919

- Utah: January 16, 1919

- Nebraska: January 16, 1919

Nebraska was the 36th state to ratify the amendment. Not only was the amendment ratified in less than 7 years, it was done in less than two.

- Missouri: January 16, 1919

- Wyoming: January 16, 1919

- Minnesota: January 17, 1919

- Wisconsin: January 17, 1919

- New Mexico: January 20, 1919

- Nevada: January 21, 1919

- New York: January 29, 1919

- Vermont: January 29, 1919

- Pennsylvania: February 25, 1919

- New Jersey: March 9, 1922

Only two states rejected the amendment. They were Connecticut and Rhode Island.

Pennsylvania held out for 5 weeks after ratification and finally saw the futility of delaying the inevitable. Congress drew up the Volstead Act or National Prohibition Act and passed it in October, just months before national prohibition would become the law of the land on January 17, 1920- one full year after ratification.

Once the surety of a Constitutional Amendment was in place, distillery owners scrambled to sell off any remaining stocks of whiskey that they had in their warehouses. In many cases, this was not possible and warehouses across the country remained stocked with liquor. With no hope of maintaining a business and with taxes due on the whiskey that remained, they dissolved their companies and sold their properties to pay outstanding debts.

The advent of Prohibition was especially hard on Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey producers. Over 200 years of rye whiskey making tradition came crashing to a halt. Even if some foresaw an end to Prohibition and maintained optimism for the future of whiskey making in America, there would not be many rye whiskey making experts alive to foster a revival. There were many reasons that rye whiskey did not survive the “Great Experiment” as well as other whiskey styles, but that discussion is a long one and will have to wait until another day…

*This is not an exclusion of slavery, human rights, women’s rights or any other extremely important politically divisive issue. The point being made is that the moral issue of temperance, which was not nearly as important or central to the foundational strength of our nation, was used specifically to divide factions within the parties and within all American communities that did not possess strong opinions about it beforehand. Temperance was presented to the people, but complete prohibition became the scheme. By leveraging this moral issue, politicians were able to contrive a “for us or against us” environment within America’s communities and manipulate the focus of citizens.