Highspire Distillery

The Wilson Distillery (1823-1893)

Highspire, Pa

Dauphin County

RD# 1

9th District

There is little doubt that Highspire Distillery would have flourished into the 20th century if not for Prohibition. In fact, the distillery was prepared to reassemble its entire ownership team and staff, original whiskey recipe, and original location after the 21st amendment brought an end to America’s “Noble Experiment” in 1933. The Baltimore based company and its owners had a great deal of success in the US and abroad with their highly sought after Highspire Rye Whiskeys. Founded in 1823, this rye whiskey producer belongs among the greats of Pennsylvania distilling.

The origins of the distillery are only slightly younger than the village in which it was built. The small borough of Highspire in Dauphin County was settled in 1814 by families that came from the towns of High and Spire in Bavaria. Just 9 years after the town was settled, Robert Wilson purchased land within the town and borrowed $900 to build his distillery. Within 3 years, he was debt free and $1000 in the black. Wilson was of Scots-Irish descent and immigrated to America in 1816 from County Down, Ulster Province in northeast Ireland. While his origins might suggest that he came to America as a distiller, his knowledge of distilling were obtained in America. Wilson first trained in Lancaster for a year and Coxestown (Estherton), just north of Harrisburg, for another 3 years after that. While his Highspire distillery’s business was small and likely only focused on central and eastern Pennsylvania markets, Robert was quite successful. His sons were wealthy men when they took over Robert’s 40-year-old business in 1863. Unfortunately, many of the Wilson family’s investments soured during the lead up to the great financial panic of 1873.

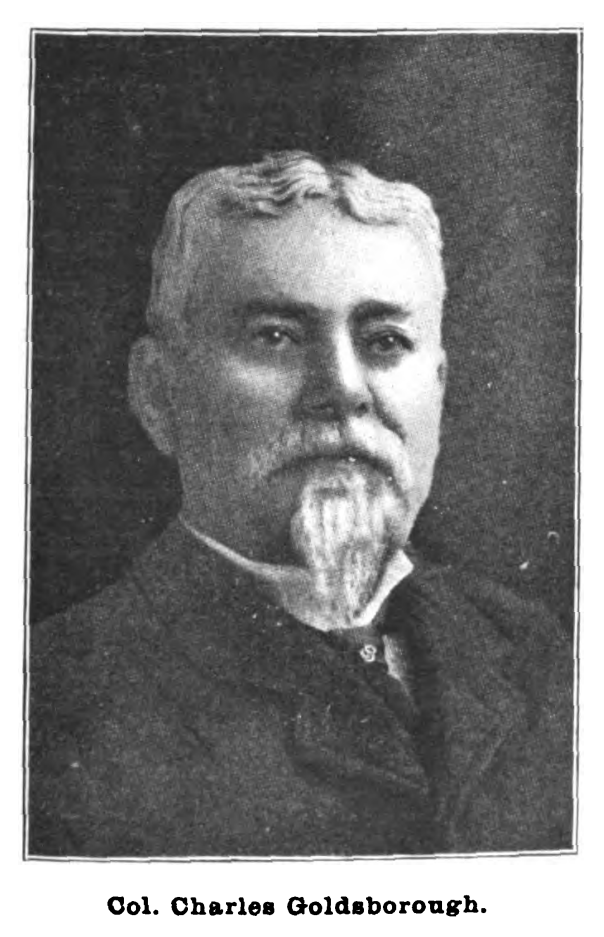

Robert Wilson’s sons sold the distillery in 1872 to the firm of Cobough & Ettle. Apparently, J.B. Ettle (of Bellefonte, Pa) was not faring well from the financial crisis either because he took his own life with a pistol to the temple in the bathroom of a Pennsylvania Railroad car in January of 1874. Ettle’s partner, Cobough, sold the distillery again the following year. It continued to change hands until coming under the ownership of Abraham Penrose Lusk in 1877. The road bordering the eastern side of the distillery property later came to be called Lusk Avenue, after A.P. Lusk who committed the final decade of his life to running the Wilson Distillery in Highspire. In his will, he provided for its purchase by an old business associate, Charles Goldsborough.

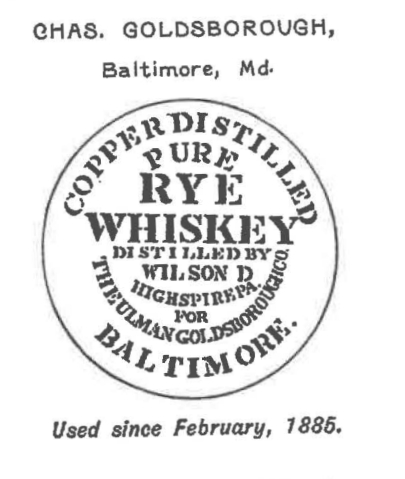

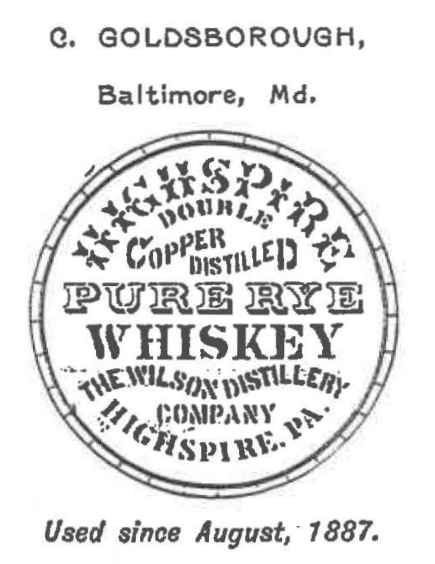

The Goldsboroughs were a prominent Maryland family from Baltimore. Charles headed the large Baltimore liquor firm of Ulman-Goldsborough that contracted with A.P.Lusk to market most of the whiskey produced at Highspire Distillery. To be clear, the company name, Wilson Distillery Company was in Pennsylvania and the Ulman Goldsborough Company kept its offices in Baltimore. It was not uncommon for Baltimore firms to purchase the whiskey they bottled from Pennsylvania distilleries. Below are some patents filed by Charles Goldsborough with Mida’s Nationsl Register of Trademarks as they appeared on the distillery’s barrel heads.

Around 9pm on June 16, 1893, the Wilson Distillery went up in flames. The fire burned until nearly midnight with the distillery buildings, cooperage, offices, and warehouse “A” (containing 5,000 barrels of whiskey most of which belonged to liquor firms and dealers throughout the country) were lost. The Harrisburg Telegraph reported that “whiskey flowed over the neighborhood and became a lake of fire. It even reached the river (Susquehanna) and burned upon the surface of the water like oil. There were not a few who scooped up the fiery liquid in buckets and drank it as it cooled.” The loss of buildings was estimated to be around $30,000 and the loss of whiskey around $150,000.

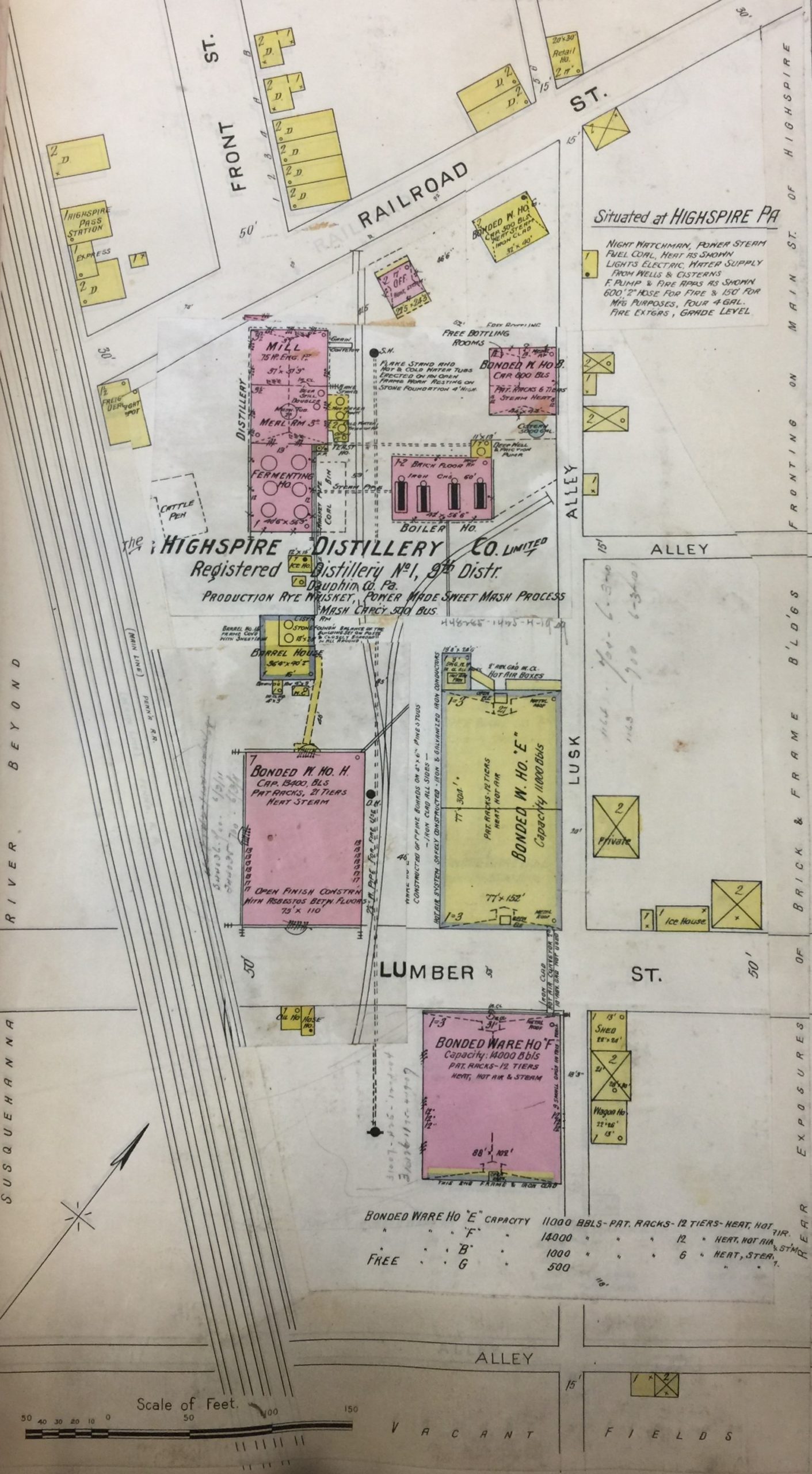

Ulman and Goldsborough went right to work rebuilding their distillery and used the opportunity to expand and improve the facility. The new distillery could produce 1000 gallons of rye whiskey per day and was capitalized at $500,000. After the rebuild, Highspire Distillery was faced with the same setbacks in production that other Pennsylvania distilleries were dealing with. The financial panic of 1893 left many distilleries with a great surplus of whiskey in their warehouses. The change in the revenue laws in 1894 also greatly depressed the market.** To help themselves and the market’s recovery, eastern distillers (including Highspire) agreed to cease production from July 1st 1896 until September 1st 1897. This was not a trust, it was an agreement which nearly all distillery owners agreed to.

In 1898, Mr. A.J. Ulman retired and Charles Goldsborough formed a new company. Now, as president with controlling interest, Goldsborough capitalized his new company at $1 million and named it the Highspire Distilling Company, Limited. Wilson whiskey was now an internationally popular brand. It was also in the crosshairs of the Whiskey Trust, which very much wanted Highspire to join their ranks. The company refused to join, saying the offered price was too low. When Charles died in 1903, he was succeeded by his eldest son. Charles Jr. served as president with Charles Francis Purnell of Baltimore as treasurer and Major Joseph C. Smith serving as secretary and superintendent of the plant.

The next generation of Goldsborough men secured their family legacy by maintaining traditional methods at their distillery while making modern improvements. Their rye whiskey maintained the 100% rye and rye malt mash bill, and the purity of the distillate was praised by pharmacists, doctors, and liquor dealers. Most of their rye grain was sourced from Michigan, but a good deal was purchased from the Susquehanna Valley’s farms surrounding Harrisburg. Their on-site cooperage produced high quality oak barrels which were filled at a rate of 6000-8000 per anum. The company touted their barrel storage rackhouses which had been designed to make every barrel visible to inspectors, helping to make leaks more easily detected and repaired. The year-round heated warehouses held over 53,000 barrels by 1905. They also maintained a mash drying facility that produced about 800,000 lbs. of dried mash each year, most of which was sold abroad. The early 20th century was very profitable for the Goldsborough’s. To meet production and shipping needs, the number of railroad sidings leading to the facility from the Pennsylvania Railroad to the loading platform had to be increased. Not even the monstrous flood of 1904 that paralyzed the town of Highspire could slow their progress.

One of the principal reasons behind the success of Highspire’s whiskey was attributed to their water quality. The Harrisburg Telegraph in 1893 read,

“The geological survey shows a narrow ledge of red shale rocks, charged with iron and carbonates and sulfates of magnesia, projecting from the planes to the northwest of the village (Highspire), and, dipping to the southeast, cropping out in the channel of the river. This run of rocks, like a mountain stream, is narrow and bounded on each side by limestone deposits of indeterminable depth and unsurpassed in quality.

The subject connected with the manufacture of fine whiskies which has created the most discussion and has been the cause of more conjecture than any other is, ‘What causes the difference in flavor between whiskies, aside from the materials from which they are made?’

If this were the only test to apply to Highspire Pure Rye Whiskey, it would entitle it to the high rank it holds in the trade, standing alone in its peculiar properties of flavor and liquified fruitage as to taste; but, owing to the character of the water from its three artesian wells, deep down in the geological strata whence its unrivaled water is drawn, it can made on a combination as to malted or unmalted grain not possible in any other rye whiskey distillery in the country.”

In 1906, the shareholders of Highspire Distilling Company, Ltd., met to discuss the retirement of the distillery’s manager of 16 years and company secretary, Major Smith. J.H. Blundin would take his place as superintendent and Robert Galt Goldsborough, Charles Sr.’s son, would replace him as secretary. Soon after the meeting, Robert moved from the family home in Maryland to Harrisburg. He would remain a socialite and prominent businessman within Harrisburg’s upper-class society until his death in 1950. R.G. Goldsborough took over the role as treasurer and secretary soon after taking on his new role in the distillery.

Once Robert took the reins of the company, it seemed the sky was the limit. With their slogan, “Wilson, That’s All,” now recognized across the globe, consumer demand for Wilson Distilling Company/HIghspire Distilling Company products distributed through Goldborough’s Baltimore-based firm was better than ever. R.G. Goldsborough would have been acutely aware of the looming threat of National Prohibition over the following decade, but, like most Pennsylvania and Maryland distillers, he had been optimistic that the country would come to its senses. Nevertheless, Robert Goldsborough was content to take advantage of the profits to be made as the years marched on and price of whiskey rose. By the time WWI’s Food and Fuel Control Act shut down American distilleries in 1917, Highspire’s warehouse supplies were already reported as being low. By 1919, the Goldsborough’s were selling off distillery equipment. The town of Highspire was losing its only industrial plant.

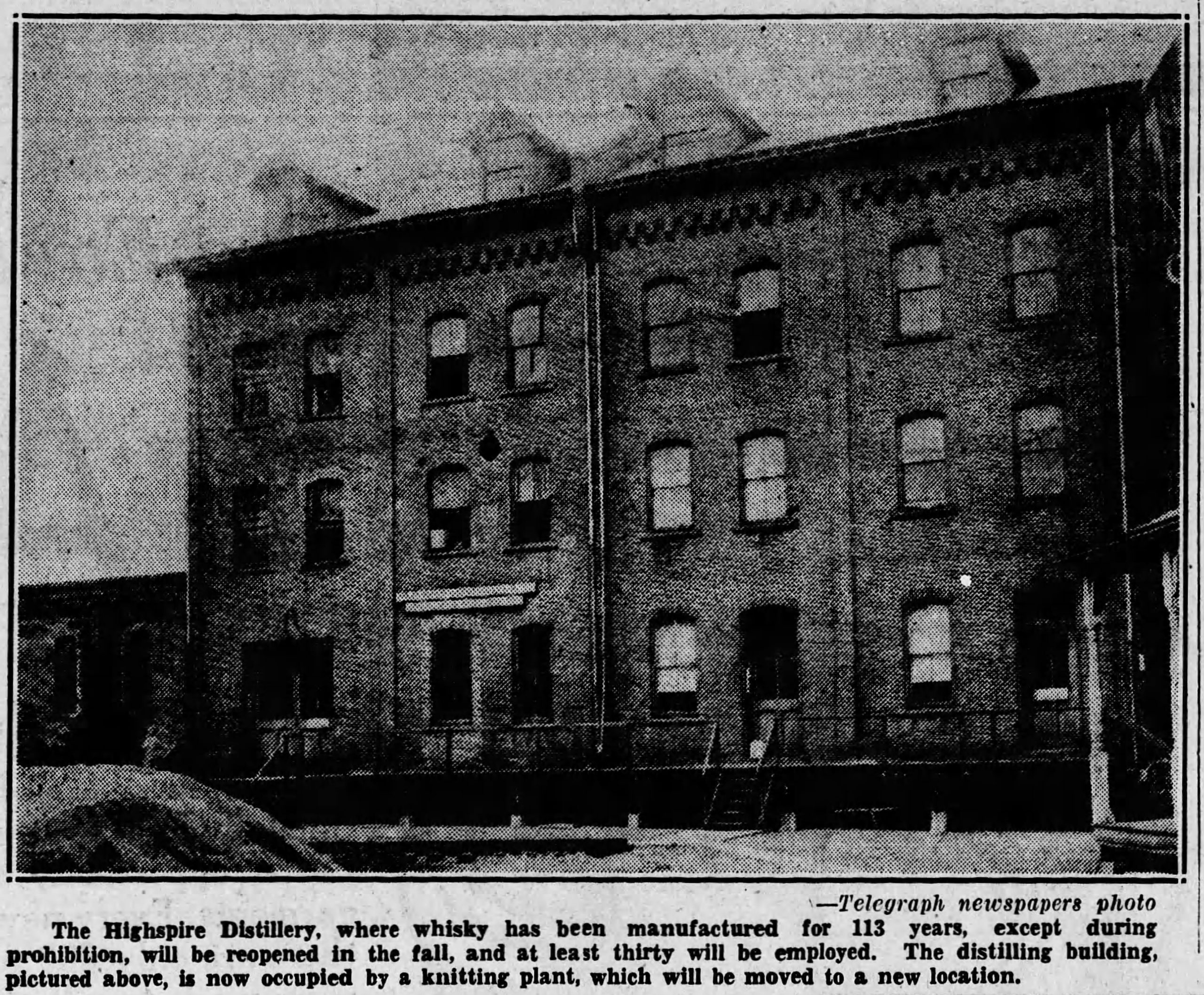

The Highspire Distillery Company did not go quietly. The distillery building itself was transformed into a knitting mill, but the warehouses were still full of whiskey. Just before Prohibition went into effect, Robert sold railroad cars full of barrels to buyers in Canada and Cuba. There were also several thefts from the warehouses between 1919 and 1924 as the bootleg market for Highspire Pure Rye Whiskey rose to $15 a quart. There were suspicions that one of the larger thefts was an inside job that involved the government watchman on duty. By 1924, the remainder of whiskey in the warehouses were removed and shipped to J.A. Dougherty and Son’s concentration warehouse in Philadelphia. Robert was able to procure a license to sell his medicinal whiskey to pharmacies. After paying the excise taxes on the whiskey, he removed 60 cases of rye whiskey from his warehouse and stored them in the facility’s unguarded bottling house while awaiting shipment. Thieves broke into the bottling house and made off with all 60 cases on March 6, 1924. The whiskey’s value on the black market was close to $7,200.

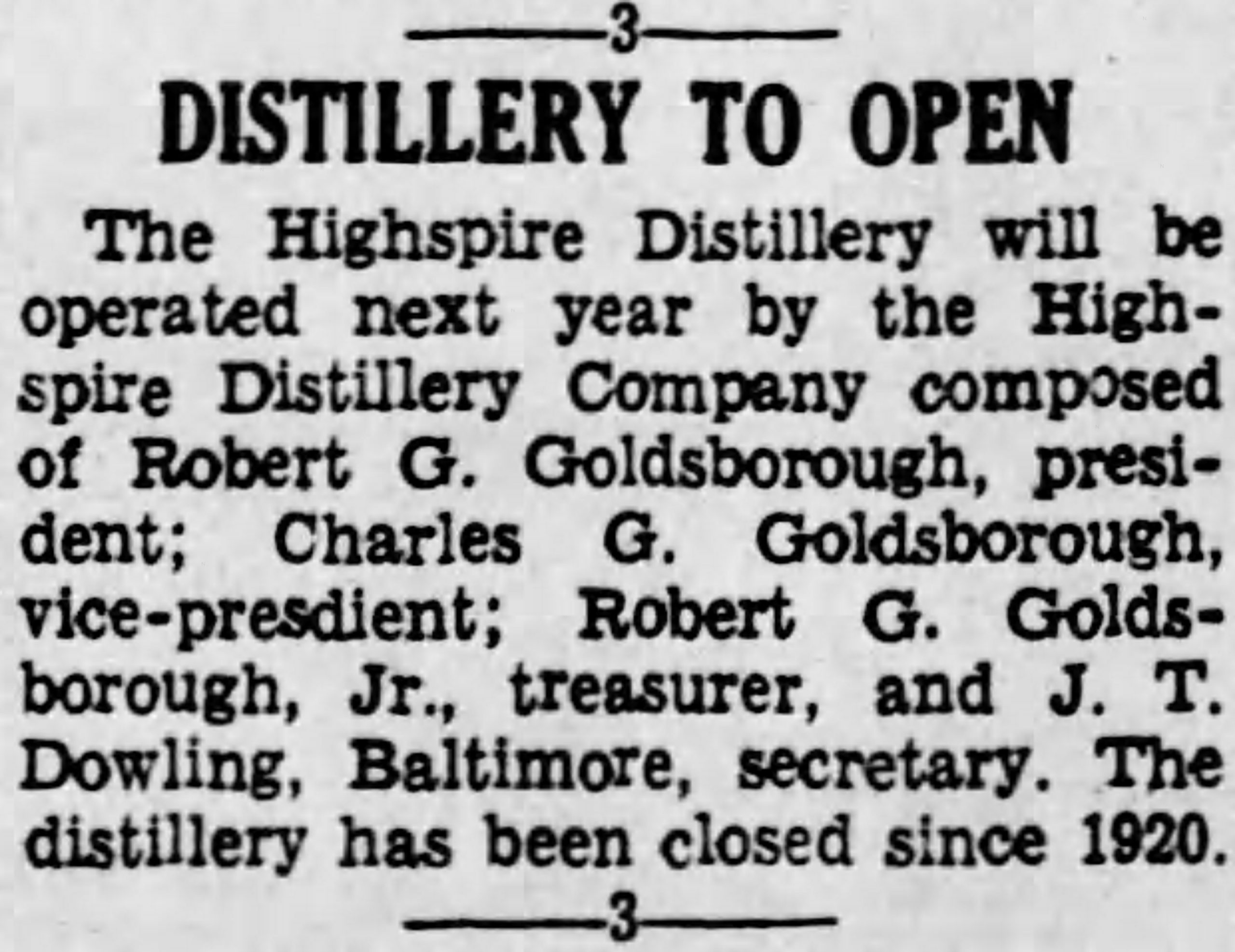

When Prohibition ended, Robert G.Goldsborough wanted to restart the distillery. He fought to regain the patent for his Highspire Pure Rye Whiskey Brand and was finally able to win it back in 1935. With the patent in hand, he reconstructed his entire team from the distillery before 1920 and issued a prospectus titled “The Return of a Famous Whiskey” to draw interest in his plan. He would serve as president with his older brother, Charles, as vice-president, Robert’s son, Robert G., Jr. as treasurer, and Jesse T.Dowling as secretary. The plan was detailed, and the company attempted to raise $350,000 by issuing 35,000 shares of preferred stock to pay for the restoration of Highspire Distillery to its former glory.

It is not known exactly what went wrong or why the company was not able to reform and rebuild, but it is certain that Prohibition and a new and unfriendly post-prohibition Pennsylvania legislature played their roles in its ultimate demise. The “Wilson” brand name, however, continued to be associated with the Wilsons and the Highspire Distillery they founded long after the hope of the Pennsylvania distillery’s reboot came to an end.

“Wilson’s Blended Whiskey” was launched after Repeal by Browne Vintners of New York. The extensive ad campaign to promote the new version of Wilson’s whiskey was launched in the spring of 1936 with the tag line, “Wilson’s, That’s All.” The ads explained that the 100-year-old whiskey was made the way it always had been, which was, of course, false. The whiskey was blended and bottled at Browne Vintner’s Wilson Distilling Co., Inc. location in Relay, Maryland. The following year, Browne Vintners went on to build a distilling plant in Bristol, Pennsylvania also called Wilson’s Distilling Company. They would merge their Hunter Baltimore Rye Distillery, Inc. with Wilson Distilling Company to make the Hunter-Wilson Distilling Company. Browne Vintners sold the Wilson brand to Seagrams in 1941. After changing hands several times, the brand now belongs to Heaven Hill.