I was talking with a distiller the other day about how little is known about pre-Prohibition rye whiskey distillers. It’s sad to think that about 200 years of generational knowledge was lost when the craft of rye whiskey-making was brought to an abrupt end in 1917. But it wasn’t just the rye distilleries that lost their footing. During the 13 years of Prohibition, many of the old guard of America’s distilling industry either died or retired from the industry. An entire generation of apprentices and journeymen lost their access to the masters that would’ve trained them. Distilling, like any other profession that requires a mastery of diverse trade skills, must be taught through hands-on instruction over the course of years. It was no small thing to lose that natural progression into the next generation of distillers. There were no “how-to” books or training seminars on whiskey making. Small details that may have been common knowledge to a pre-Pro distiller may have had a huge effect on the final product… but we’d never know because those details are lost to us! There’s no doubt that modernization throughout the history of distilling altered the distiller’s craft and changed the way the masters taught their students, but there had always been an “old distiller” to guide the next generation. In the 21st century, we find ourselves without an “old guard” to guide craft distillers in their efforts to recreate older American whiskey styles. Even our American bourbon distilling traditions are more guided by the Canadian Seagram’s method and approach to distilling than they are by their own historic approach to production. We barely know who distilled the whiskey, let alone what their process was in creating it. Perhaps getting to know the distillers, researching their distilleries, and looking for scraps of information that could reveal forgotten techniques might help American whiskey find its foundations again.

So who were these “old guard” distillers, anyway? Distilling was an insular trade and the men that ran distilleries and their stills were not well known outside of their own small circles. In some cases, men earned stellar reputations and took on the role of an instructor or master distiller. In Pennsylvania, one famous family with several generations of master distillers was the Frost family. James Frost was brought on as a distiller at Gibsonton Mills Distillery (later known as Moore & Sinnott Distillery), in 1870. He was hired by Henry Gibson to work under his plant superintendent, Thomas Daly. Gibson (or more likely, Thomas Daly) felt Frost lacked some expertise, so they sent him to train under a master distiller in Gray’s Landing- the old, famous master distiller, William Gray- for EIGHT years until Gibson and his partners, Moore & Sinnott, felt he was ready to be brought back on as the plant’s distiller. 8 YEARS!!! Can you imagine how much a man had to know to be able to run a large distilling plant in the 1880s? It boggles the mind.

But who has ever heard of the Frost family? Or Thomas Daly? These may have been very important PA rye whiskey distillers, but they are not well-known names in the whiskey world today. That’s unsurprising, I suppose, when you consider how little information is available about PA rye whiskey history, but let’s consider even master distillers from recent memory. Do you know who the master distiller was from Four Roses before Brent Elliott? Okay, that’s an easy one. Jim Rutledge. But before Jim Rutledge? That was Ova Haney. And while many people may recognize the name Ova Haney, I hope you get my point. Master distillers have not always been superstars. They worked hard behind the scenes to make other men very wealthy. Their knowledge and insights were kept secret and maintained by these gatekeepers to the industry. Distillers, superintendents, managers…they were invaluable to the industry even when no one knew who they were. There was little need to write anything down because the knowledge was kept by these men. They were ones that knew every aspect of production. The big name connected to any old brand name, however, was always the company’s owner and the distiller’s boss. In keeping with the example of Four Roses, the name we associate with the pre-Pro era was Paul Jones. But Paul Jones, Jr. died in 1895 and it’s not clear if his rectifying business ever required him to run a still! As a rectifier, he could have been bottling, blending, or compounding whiskeys. When we talk about pre-Pro distillers, what we’re usually talking about and praising is the business savvy of distillery OWNERS, not of the men that ran operations.

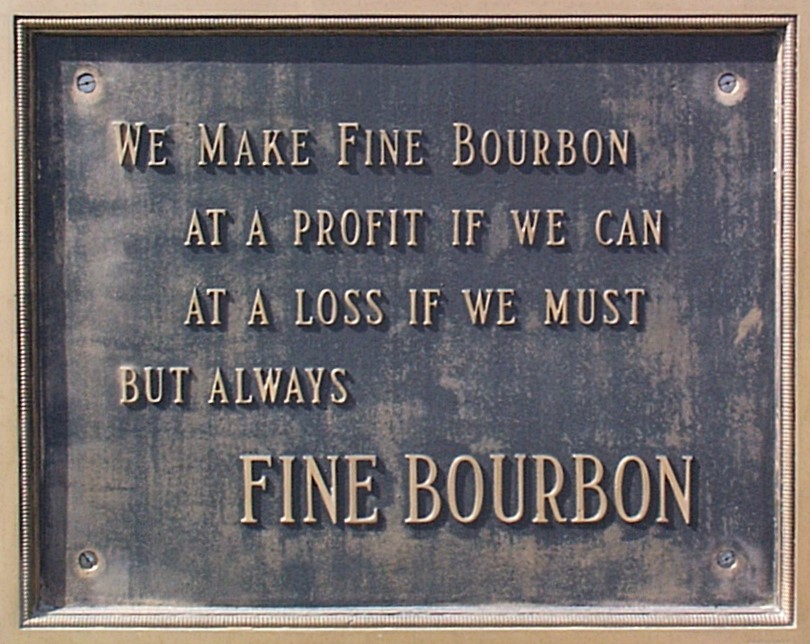

Over the generations, the owners went from being the man getting his hands dirty in the mill/distillery to being the company president who hired other men to do the work their father/uncle/grandfather used to do. The habit of keeping the name of the original owner/distiller stuck, but 3 or 4 generations in, distillery owners often had no relation to the original owner at all. And once corporations moved into the picture in the 1890s, all bets were off. Distillers were just “some guy” that ran the plant. They sometimes held positions as board directors within a company, but, again, were bit players in the game- even as they were solely responsible for the quality of the distillery’s product. The first time you start seeing distillers come out of the shadows is just after Prohibition when the large companies were desperate to earn consumer support and would drag an old distiller out of retirement for their stamp of approval and authenticity. But the Mad Men era wiped them away again into obscurity. Craft and credibility were buried all over again. And all of those trade secrets and unique processes were replaced with industry standardization. The rectifying column still, the stainless steel tank, and the laboratory replaced the hand-made craft whiskey distiller. I’m not belittling product consistency or modernization. I’m just saying that the sign outside of Stitzel Weller’s Distillery was becoming less and less applicable to the industry.

Bourbon whiskey drinkers love to love bourbons with any connection to Stitzel Weller. And when you ask most people who the master distiller was at Stitzel Weller they’d say, “Duh. Pappy Van Winkle.” A whiskey geek might say, “No, that’s a trick question, he wasn’t ACTUALLY a distiller.” And another would chime in with “Yes, he was. Stitzel Weller distilled from 1935 to 1972.” And…they’d all be…not wrong. Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle was considered an “executive distiller.” The man working the fermenters and hand-making all that bourbon for Stitzel Weller in the 1930s, however, was William H. McHill. We don’t tend to talk about him as much because his name wasn’t directly associated with those famous bottles of like Mammoth Cave or Old Fitzgerald bourbons- even if he was the taste tester and the man behind both brands. Will “Boss“ McHill taught his old school, pre-Pro distilling techniques to Andrew “Andy” Corcoran for over a decade before Corcoran took his place as master distiller in 1952. “Boss” McHill died at the age of 87, but not before making Stitzel Weller famous for its “no chemist’s allowed” mentality- his old school distiller mentality. And the newspapers loved to print how “The Boss” at Stitzel Weller was traditional and how the new Seagram’s lot with all their test tubes and science-y, quality control thingamajigs were too chemistry focused. This “tradition vs. science” thing in the 1940s and 50s was not new. It was a reboot of the “straight whiskey vs. rectifier” argument 40 years earlier. It was just a new spin on an old story. What was unique was that distillers were in the newspapers at all. It had always been the owners that took the credit for their products. McHill is also quoted in 1945 saying “Whiskey is much better today than the old brands” and he’d be “glad to go into it further with any of the oldsters who wish to take umbrage.” I love the contradiction in the man- not to mention the brass of an 80-year-old man calling other people “oldsters”! 😊 McHill got his first job working in a distillery in 1880 and had been distilling whiskey since 1897, so he had 65 years of industry experience by 1945 and was the oldest active distiller alive at the time, so I can’t imagine who he was talking to! His “rival” from Seagrams was Dr. E.H. Scofield. Scofield believed that science and the laboratory was all that was necessary to achieve uniformity in a desirable product. He promoted the use of “psychometric equipment” to test panels of consumers and allowed average citizens to determine what Seagram’s products should taste like. “We have discovered that people simply do not like the taste of whiskey,” Scofield explained to a Louisville reporter from the Courier Journal in 1943. “So we keep experimenting to find a blend that is pleasing to a greater percentage.” This show of “whiskey taster vs. test tube” made great press, but it also exposed a new rift in the distilling community. Corporate interests were demanding products that would appeal and sell to a broader consumer base. The big companies were still not satisfied with all the money that was coming in. Production would move away from traditional, old school techniques in favor of the faster, cheaper, larger production capacity methods. We can argue the merits of both schools of thought, but the reality was that the Seagrams way of making whiskey came out on top. The days of Will McHill were over.

It’s hard to talk about whiskey history without talking about the real men behind the whiskeys and what they knew. Aside from the Beam family and the information gleaned from the many proud Beam descendants alive today, we don’t know much about what America’s distillers knew. That same distiller I mentioned I was talking to about pre-Pro distillers said, “The old techniques are lost to time.” And he’s right. I mean, the distilling industry didn’t even remember what a three chamber still was until Todd Leopold reminded everyone. They weren’t even gone that long! There were several three chamber stills that were still in operation during the 1950s and 60s! What we really need are old notebooks and insights into these men’s processes. What temperatures did they use throughout the mashing process? How long were those resting periods as they cooked? How long did they ferment? How did they maintain their yeast strains? What were they looking for throughout the process to maintain consistency? What was their favorite color? Okay, joking about that last one. But I can tell you, as an artist, when you’re struggling with a technique and a master comes along and simply says, “try this instead,” you can’t help but look back afterward and wonder how you were ever doing it any other way. Distillers, like fine artists, also struggle with the process and look for those masters to guide them out of their ruts. We used to have hundreds of highly skilled distillers in this country, all with their own proprietary knowledge that they passed down from one generation to the next. And they didn’t make bourbon whiskey the way the Beams did. How wonderful it would be to have a small window into how rye whiskey was once made…Because you need a lot more than just a mash bill and a still to get you there. “The Boss” McGill said it best. “Nature and the old-time ‘know how’ of a Master Distiller get the job done here.” I just wish we knew more about what they knew.